Texts

Every Wednesday, Sabzian publishes texts on cinema in Dutch, English or French.Chaque mercredi, Sabzian publie des textes sur le cinéma en néerlandais, en anglais ou en français.Elke woensdag publiceert Sabzian teksten over cinema in het Nederlands, Engels of Frans.

Een rondetafelgesprek met Hans Bryssinck, Ben De Raes, Leni Huyghe en Maja-Ajmia Yde Zellama

Dit gesprek bouwt voort op eerdere gesprekken die we met Sabzian voerden met studenten en alumni van de Vlaamse filmscholen KASK, RITCS en LUCA, met als doel de ervaring van het filmmaken in Vlaanderen en Brussel, en de bijbehorende subsidiecontext in kaart te brengen. In het verlengde van deze gesprekken spreken we de komende maanden met verschillende filmmakers die zich elk in een andere fase van hun carrière bevinden. Dit is het tweede deel van het gesprek waarin regisseurs aan het woord komen die recent hun eerste langspeelfilm realiseerden, die in 2025 in première ging. De vier deden dat telkens binnen een specifieke productiecontext. Het gesprek focust op de verwachtingen, obstakels en eventuele ontgoochelingen, zowel tijdens het maakproces als achteraf.

Je m’étonne un peu de me trouver sur cette estrade tout seul. J’aurais préféré, étant donné l’esprit dans lequel a été réalisé Zéro de conduite, vous offrir à la manière des girls anonymes, comme préface fugitive à la projection du film, un salut chorégraphique en compagnie de tous mes collaborateurs. Une ronde aurait, je crois, avantageusement remplacé tous mots bafouillés.

Ik ben een beetje verbaasd hier helemaal alleen op dit podium te staan. Ik had liever, gezien de geest waarin Zéro de conduite tot stand is gekomen, zoals de anonieme girls dat doen, als een vluchtige inleiding op de vertoning van de film een choreografische groet gebracht samen met al mijn medewerkers. Een rondedansje zou, denk ik, alle gestamelde woorden beter hebben vervangen.

I’m a bit surprised to find myself alone on this stage. Given the spirit in which Zéro de conduite was made, I would have preferred to offer you, like the anonymous girls, as a fleeting preface to the film’s screening, a choreographed greeting together with all my collaborators. A round dance would, I believe, have favourably replaced any stammered words.

L’œil de l’Homme, “dans l’état actuel de la Science”, n’est guère plus sensible que son cœur. Cette constatation serait déprimante, si nous n’avions quelque raison d’espérer encore en la pellicule cinématographique.

Het oog van de Mens, “in de huidige staat van de Wetenschap,” is nauwelijks gevoeliger dan zijn hart. Deze constatering zou deprimerend zijn, als we niet nog enige hoop hadden in de cinematografische filmstrook.

The eye of Man, “in the present state of Science,” is hardly more sensitive than his heart. This observation would be depressing were it not that we still have some reason to place our hopes in cinematographic celluloid.

Een rondetafelgesprek met Hans Bryssinck, Ben De Raes, Leni Huyghe en Maja-Ajmia Yde Zellama

Dit gesprek bouwt voort op eerdere gesprekken die we met Sabzian voerden met studenten en alumni van de Vlaamse filmscholen KASK, RITCS en LUCA, met als doel de ervaring van het filmmaken in Vlaanderen en Brussel, en de bijbehorende subsidiecontext in kaart te brengen. In het verlengde van deze gesprekken spreken we de komende maanden met verschillende filmmakers die zich elk in een andere fase van hun carrière bevinden. In dit gesprek komen regisseurs aan het woord die recent hun eerste langspeelfilm realiseerden, die in 2025 in première ging. De vier deden dat telkens binnen een specifieke productiecontext. Het gesprek focust op de verwachtingen, obstakels en eventuele ontgoochelingen, zowel tijdens het maakproces als achteraf.

A Conversation with Lucrecia Martel

In October 2025 at the 63rd edition of the Viennale, Sabzian sat down for a talk with Lucrecia Martel, discussing how Nuestra Tierra echoes political concerns found throughout her body of work, the pitfalls of thinking of cinema in terms of fictions versus documentary, the trappings of both style and of the film industry, and how to integrate a very diverse array of imagery into a cohesive whole. Martel: “[T]he film, beyond the historical questions, is also a reflection on my own work. I’m someone who ended up making cinema. I never even said that I wanted to be a director or anything like that. But, well, it became my work. And it’s a reflection on what this work is, how powerful it can be.”

“I believe” Akerman famously said in 1976, “that form highlights class relations within the image.” In other words, the truly political claim of her film was precisely to defend its autonomy as a work of art. An autonomy that Jeanne tries to defend in her own life. Not as a sphere she enjoys or that we should celebrate but rather as a space defined by its own rules, self-governed. In other words, her resistance to what could make her lose control over her actions also offers Akerman a way to make art out of it. For Jeanne, housework is a space that is still protected from the estrangement of work under capitalism.

Vanachter een muurtje, door een kijkgat, smeekt een meisje om aandacht: “Film me, dan heb ik een beeld.” De camera zoekt en vindt haar, hoewel ze amper zichtbaar is. Haar drang naar beeldwording spreekt luider dan het ontoereikende antwoord dat ze krijgt. Het is niet het eerste, noch het laatste kind dat het beeldkader opeist in With Hasan in Gaza (2025). Kamal Aljafari en cameraman Hasan beantwoorden hun verzoeken door via pans en tilts kinderen in het frame te vangen. Vervolgens kijken ze glimlachend de lens in, en vormen met hun handen een teken van vrede.

Three Il Cinema Ritrovato visitors each discuss one film they saw at this year’s festival in Bologna that has stayed in their memory.

Drie bezoekers van Il Cinema Ritrovato bespreken elk één film die ze dit jaar op het festival in Bologna zagen en die hen is bijgebleven.

Sirât by Oliver Laxe

If Laxe’s true subject is detachment and indifference, and his film is a form of punishment, then that results in a peculiar cruelty. In various interviews, Laxe says that Sirât arose from a “wound,” which he traces back to Gestalt psychology. “Art is pushing boundaries, spirituality is pushing boundaries, and that’s where you get to know yourself,” he says. The word “wound” also encapsulates the duality of the film: wounds can be healed and inflicted. Strangely enough, Sirât does both.

Sirât van Oliver Laxe

Als Laxe’s ware onderwerp onthechting en onverschilligheid is, en zijn film een vorm van bestraffing, dan resulteert dat in een eigenaardige wreedheid. In verschillende interviews zei Laxe dat Sirât voortkwam uit een “wonde”, die hij terugvoert op de Gestaltpsychologie. “Kunst is grenzen verleggen, spiritualiteit is grenzen verleggen, en dáár leer je jezelf kennen,” zegt hij. In het woord “wonde” schuilt ook de dualiteit van de film: wonden kunnen worden geheeld en toegebracht. Vreemd genoeg doet Sirât beide.

All my life…I’ve been waiting for you. De felrode bloemen, de verweerde schutting en de blauwe hemel zijn de hoofdfiguren van deze korte film. Met een telelens vertelt Bruce Baillie in een drie minuten durende panbeweging een liefdesverhaal tussen de kijker en de struiken. Wat is er zo bijzonder aan dit Californische zomertafereel?

Bugonia (2025) by Yorgos Lanthimos

[Bugonia] sets itself in a broader genre of conspiracy movies such as Alan Pakula’s 1974 The Parallax View, Philip Kauffman’s 1978 Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and John Carpenter’s 1988 They Live. In such movies, aliens or conspirators are generally de-individualized so that they can function effectively as metaphors for “the system”. A way to see such movies is as an attempt to thematize conflict in late capitalism, meaning a contradiction that cannot express itself anymore in the terms of class war. For atomized workers, the conspiracy theory provides a “useful fiction” to understand the social totality itself.

From [Frans van de Staak], I learned not only how to make films but also how to be determined in doing so. He was open, unassuming, modest, but very strong. He was one of those rare people whose life and art matched perfectly. He spoke very little. He would laugh and say, “I started talking very late; my mother took me to the doctor for that.” Yes, his films tend to be modestly silent, but they could delve deeply into what he was telling, reaching the very essence of the subject, without any bombast.

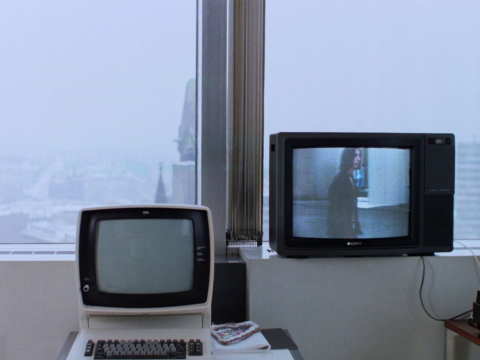

Mochten we het over cinema hebben, en niet over televisie, dan zou de ideale omroepster lijken op de variétépresentatrice: een knappe, charmante en zwierige meid in een strak topje. We zouden natuurlijk doeltreffendere formules kunnen bedenken zoals in de “Witte tanden”-reclamespots voor tandpasta bijvoorbeeld, maar in het hoofd van de televisiekijker geldt de tv-presentatrice binnen de kortste keren als een persoon uit zijn privékring: iemand van wie het dagelijkse bezoek door het hele gezin en in de eerste plaats door de vrouw des huizes wordt aanvaard.

Si la télévision était le cinéma, l’idéal de la speakerine s’identifierait à peu près à celui de la présentatrice de music-hall : jolie fille en maillot, accorte et pleine d’entrain. On pourrait, bien sûr, imaginer des formules plus intimement persuasives du genre « Dents blanche », par exemple, mais la speakerine de télévision s’institue très vite dans la conscience du téléspectateur comme un personnage de sa vie privée : un personnage dont la visite quotidienne doit être acceptable par toute la famille et d’abord par la femme.

If television were cinema, the ideal speakerine would be someone more or less like the music hall presenter: a pretty girl in a bathing suit, agreeable and spirited. Of course you can imagine options that are more intimately persuasive, in the genre of the “White Tooth Smile,” for example, but the speakerine quickly installs herself in the mind of the television viewer as a figure from his private life: a person whose daily visits must be suitable for the whole family, especially for the wife.

André Bazin in gesprek met Jean Renoir en Roberto Rossellini

Wat heeft u bij televisie gebracht die, met name onder intellectuelen, nogal slecht aangeschreven staat?

Renoir: Ik ben bij televisie terechtgekomen omdat ik me heb doodverveeld bij heel wat recente films en ik me eigenlijk minder verveeld heb bij bepaalde tv-uitzendingen. Ik moet er wel bij zeggen dat de tv-uitzendingen die me het meest hebben geboeid interviews waren die ik op de Amerikaanse televisie zag. Ik heb de indruk dat televisie dankzij het interview een gevoel voor close-ups heeft ontwikkeld dat maar uiterst zelden voorkomt in films. [...]

Rossellini: Daar wil ik graag iets over opmerken. In de moderne samenleving heeft de mens een enorme behoefte zijn medemens te leren kennen. De moderne maatschappij en de moderne kunst hebben de mens helemaal kapotgemaakt. De mens bestaat niet meer en de televisie helpt ons om de mens terug te vinden. De televisie, een kunst die nog in haar kinderschoenen stond, heeft het aangedurfd naar de mens op zoek te gaan.

Un entretien d’André Bazin avec Jean Renoir et Roberto Rossellini

Comment avez-vous été amené à la télévision qui, pourtant, chez les intellectuels notamment, ne bénéficie pas d’un préjugé favorable ?

Renoir : Je suis venu à la télévision parce que je me suis prodigieusement ennuyé lors de la présentation récente de très nombreux films et que je me suis moins ennuyé à certains spectacles de télévision. Je dois dire que les spectacles de télévision qui m’ont le plus passionné sont certaines interviews que j’ai vues à la télévision américaine. [...]

Rossellini : Je voudrais aussi faire une remarque à ce propos. Dans la société moderne, l’homme a un besoin énorme de connaître l’homme. La société moderne et l’art moderne ont détruit complètement l’homme. L’homme n’existe plus et la télévision aide à retrouver l’homme. La télévision, art qui commençait, a osé aller à la recherche de l’homme.

An Interview with Jean Renoir and Roberto Rossellini

Television is still rather frowned on – particularly by the intellectuals. How did you come to it?

Renoir: Through being immensely bored by a great number of contemporary films, and being less bored by certain television programs. I ought to say that the television shows I’ve found most exciting have been certain interviews on American TV. I feel that the interview gives the television close-up a meaning that is rarely achieved in the cinema. [...]

Rossellini: Let me make an observation on that note. In modern society, men have an enormous need to know each other. Modern society and modern art have been destructive of man: man no longer exists – but television is an aid to his rediscovery. Television, an art without traditions, dares to go out to look for man.

Televisie is de menselijkste onder de mechanische kunsten

Televisie is in de eerste plaats een dagelijkse, intieme band met het leven, met de wereld die elke dag ons gezin binnendringt, niet om onze intimiteit te schenden, maar integendeel om erin te worden opgenomen en om haar te verrijken. Of om het nog preciezer te verwoorden: in de eindeloze massa van al deze elementen geeft de televisie de mens voorrang. Telkens als iemand die het verdient bekend te worden het tv-blikveld betreedt, wordt het beeld sterker en wordt iets van die persoon aan de kijker vrijgegeven.

La T.V. est le plus humain des arts mécaniques

La télévision, c’est d’abord l’intimité quotidienne avec la vie, le monde qui pénètre chaque jour dans notre foyer, non pour violer notre intimité, mais au contraire pour s’y intégrer et l’enrichir. Plus précisément encore, dans la variété infinie de cette révélation, la télévision favorise l’homme. Chaque fois qu’un être humain qui mérite d’être connu entre dans le champ de l’iconoscope, l’image se fait plus dense et quelque chose de cet homme nous est donné.

Television maintains, first of all, a quotidian intimacy with life and the world, such that it penetrates every day into our living rooms, not to violate our privacy, but rather to become part of it and enrich it. Even more precisely, TV, in the infinite variety of its revelations, favors man. Each time a human being who deserves to be known enters into the field of this iconoscope, the image is made richer and something of this man is rendered to us.

Kritiek was voor Bazin een publieke én dagelijkse bezigheid. In de naoorlogse jaren was hij betrokken bij ongeveer elk tijdschrift dat ook maar iets met de beginnende filmcultuur te maken had. Een proces dat zou culmineren in de oprichting van Cahiers du Cinéma in 1951, samen met Jacques Doniol-Valcroze en Joseph-Marie Lo Duca. Het is ook rond die tijd dat zijn fragiele gezondheid voor het eerst kritiek werd. Onder meer om die reden zou Bazin, gekluisterd aan zijn bed, zich op televisie richten. Hij ging de beeldbuis als een belangrijk onderdeel beschouwen van de beeldenwereld waarvan hij de beschrijver wilde zijn.

Bazin a fait de la critique une occupation publique et quotidienne. Dans l’après-guerre il s’engage dans la plupart des magazines ayant un lien quelconque avec les débuts de la culture cinématographique. Cet engagement atteint son apogée lorsqu’il fonde Les cahiers du cinéma en 1951 avec Jacques Doniol-Valcroze et Joseph-Marie Lo Duca. C’est aussi à cette époque que son état de santé, déjà fragile, se dégrade au point de devenir critique et qu’il se retrouve cloué au lit. C’est entre autres pour cette raison qu’il s’orientera vers la télévision. Il estime que le petit écran occupe une partie importante dans le monde de l’image dont il veut être le descripteur.

Criticism was both a public and daily activity for Bazin. In the postwar years, he was involved in just about every magazine that had anything to do with early film culture. This was a process that would culminate in his founding, along with Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and Joseph-Marie Lo Duca, of Cahiers du Cinéma in 1951. It was also around this time that his fragile health first became critical. It is for this reason, among others, that Bazin, stuck in his bed, turned to television. He came to see the tube as an important part of the visual world, and he wanted to describe it.

Through a mix of cultural neglect and self-absorption, experimental cinema has often remained outside vital contemporary discourses, for better or worse. Take for example its most towering figure, Stan Brakhage. Between the late 1950s and early 2000s, in nearly twenty films dealing with animals, Brakhage, more radically than anyone else, rendered amorphous the distinctions between looking and being looked at, subject and perception, human and non-human. Yet his work is rarely addressed from this vantage point. Surveying the repertoire of experimental and artists’ films for animal presence inevitably brings up many other formidable names. The most atypical figure who might feature in such a hypothetical catalogue could be the Berlin based experimental filmmaker Karl Kels, whose fascination with the zoological inspires both awe and admiration.

Eloge de l’inattendu

La magie du cinéma, c’est quelque chose qui surgit, que personne n’a prévu : c’est ce qui advient en plus de tout le travail, des outils matériels, du scénario, etc. Dans ma vie d’actrice, ce sont les rencontres et les surprises qui m’attirent, qui m’enchantent même.

Lofzang op het onverwachte

De magie van cinema is iets dat plotseling verschijnt, iets dat niemand had kunnen voorzien: wat er gebeurt, naast al het werk, de materiële middelen, het scenario, enz. In mijn leven als actrice zijn het de ontmoetingen en de verrassingen die me aantrekken, die me zelfs betoveren.

In Praise of the Unexpected

The magic of cinema is something which leaps out, which isn’t planned: it’s what happens beyond all the work, the materials tools, the script, etc. In my life as an actress, it’s the encounters and surprises which attract, or even enchant, me.

Enkele seconden van La pianiste (Michael Haneke, 2001) worden in beslag genomen door een minimalistische compositie: een witte, onbeschreven enveloppe rust op de zwarte lak van een piano. Er weerklinkt een stuk van Schubert dat wordt gespeeld door Walter Klemmer, een student die beweert hopeloos verliefd te zijn op zijn pianolerares, professor Erika Kohut. De enveloppe in kwestie wordt geopend achter een gebarricadeerde deur in het appartement van Erika en haar moeder.

Annette Apon (1949) est une cinéaste, scénariste et productrice néerlandaise. En 1973, elle collabore à la production du film Uit het werk van Baruch d’Espinoza 1632–1677 de Frans van de Staak, dans lequel elle apparaît également. Le film est présenté le 29 septembre 2025 à la CINEMATEK de Bruxelles dans le cadre d'une rétrospective consacrée au réalisateur, accompagné de Terzake (1977) et précédé de cette introduction.

Annette Apon (1949) is een Nederlandse filmmaker, scenarist en producent. In 1973 speelde en werkte zij mee aan de productie van Frans van de Staaks Uit het werk van Baruch d’Espinoza 1632–1677. Op 29 september 2025 werd deze film, samen met Terzake (1977), in CINEMATEK in Brussel vertoond in het kader van een retrospectieve van Van de Staak, voorafgegaan door deze introductie.

October 4

What is it, in essence, that Fellini doesn’t like? The poverty, the sloppiness, the coarseness, the awkward, almost anonymous pedantry with which I’ve shot the scene. Fine, I agree. It was my first experiment. For the first time in my life I found myself behind a movie camera, and this movie camera was all beat up, old, and could hold only a little film at a time. I was supposed to film an entire scene in a day. And the actors too were in front of a movie camera for the first time. What was I supposed to do, work a miracle? Yes, of course, Fellini had been expecting a miracle.

Gedurende de montage beslist de maker hoe een shot voorafgegaan en opgevolgd moet worden door de overige shots. Geluid komt niet na (of naast) het beeld; geluid is zichtbaar op het scherm, is dus in het beeld, en komt uit het beeld, is om het filmscherm, is een omhulsel van het filmscherm

During editing, the filmmaker decides how each shot should be preceded and followed by other shots. Sound does not come after (or alongside) the image: sound is visible on the screen, it's part of the image, it comes out of the image, it's all around the screen, sound embraces the screen.

Julian, maar evengoed andere recente films als Skunk of Small Things Like These en zeker Close, capteren feilloos de hedendaagse gevoeligheid waarin sentimentele druk de ultieme munteenheid van artistieke kwaliteit is geworden. De zogenaamde “mokerslag” die deze films uitdelen, is allerminst emancipatorisch. Pijn en verlies lijken de enige toegelaten sleutels tot diepgang. Elk gevoel wordt met zwaar geschut afgedwongen: grensoverschrijdend gedrag in Julie zwijgt, incest in Dalva, pestgedrag in Holly, Un monde en Skunk, zelfverminking in Girl, zelfdoding in Close en een terminale ziekte in Julian. Alsof enkel het noodlottige leven waarde heeft.

Waar de gebroeders Dardenne doorgaans een transparante houding aannemen met de camera als verbindend instrument tussen kijker en personage, lijken ze in de openingsscène van Jeunes mères net een spel te spelen met de kijker en diens verwachtingen. Het kader stuurt en zet op het verkeerde been met het oog op een verrassingseffect. Wat schuilt er achter dit schijnbaar manipulatieve openingsshot?

While the Dardenne brothers typically assume a transparent attitude with the camera functioning as an instrument connecting viewer and character, the opening scene of Jeunes mères seems to be toying with viewers and their expectations. The frame guides and misleads viewers with the aim of creating a surprise effect. What’s behind this apparently manipulative opening shot?

De televisie laat ons kennismaken met een nieuwe opvatting van de aanwezigheid, die vrij is van elke zichtbare menselijke inhoud en die we uiteindelijk kunnen terugvoeren tot de aanwezigheid van de voorstelling an sich. Een tv-trackshot glijdt nooit tweemaal over dezelfde plekken. Er zijn maar zoveel identieke kadreringen als er identieke bladeren aan de bomen hangen. Laten we het beeld koesteren dat we nooit tweemaal te zien zullen krijgen.

Television gives rise to a new notion of presence, void of all visible human content – nothing, in short, but the presence of the spectacle to itself [la présence du spectacle à lui-même]. A tracking shot, in television, never passes through the same place twice. No two framings are alike, any more than there are identical leaves on trees. Let us savor the image that we will never see twice.

La télévision fait apparaître une notion nouvelle de présence, pure de tout contenu humain visible et qui ne serait en somme que la présence du spectacle à lui-même. Un travelling de télévision ne passe jamais deux fois par le même endroit. Il n’y a pas plus de cadrages identiques que de feuilles d’arbres superposables. Aimons l’image que jamais nous ne verrons deux fois.

Jacq Firmin Vogelaar and Frans van de Staak

The way the actors stand there is as important as the text they utter – everything must become equally important, and therefore meaningless, because then it dissolves into itself. The texts you hear in the film are no longer the texts you read, although just as many images can be associated with them. The text has disappeared in the film, has sunk into it. In combination with these film images, you can say that this text materially no longer exists.

J.F. Vogelaar en Frans van de Staak

Zoals de acteurs er bij staan is even belangrijk als de tekst die ze uitspreken – alles moet even belangrijk worden, en daardoor betekenisloos, want dan lost het zich op. De teksten die je hóórt in de film zijn niet meer de teksten die je léést, al kunnen daar net zo veel beelden mee geassocieerd worden. De tekst is in de film verdwenen, daarin weggezakt. In combinatie met deze filmbeelden kan je zeggen dat die tekst materieel niet meer bestaat.

Albert Serra’s Tardes de soledad [Afternoons of Solitude] (2024)

The viewing box that is cinema is presented to us in a stripped-down form: as permitted voyeurs, balancing between identification and sadism, hoping for a “good” outcome, we watch what we are given to simply watch. The horror of the violence becomes an intimate and almost sensual spectacle of colour fields and plasticity, in which yellow-pink and red cloths, red walls, light yellow sand, glistening dark red blood, white banderillos, and the green, red-black, and white-yellow dressed, almost dancing matadors merge into a plastic feast of colours and bodies. Are we being given what we long to see? Why, then, are we bored?

Albert Serra’s Tardes de soledad [Afternoons of Solitude] (2024)

De kijkdoos die cinema is, wordt ons in een uitgeklede vorm gepresenteerd: als gepermitteerde voyeurs, balancerend tussen identificatie en sadisme, hopend op een “goede” uitkomst, kijken we naar wat ons gegeven wordt om er, eenvoudigweg, naar te kijken. De gruwel van het geweld wordt een intiem en haast zinnelijk spektakel van kleurvlakken en plasticiteit, waarin geelroze en rode doeken, rode muren, lichtgeel zand, glinsterend donkerrood bloed, witte banderillos en de groen-, roodzwart- en witgeel geklede, haast dansende matadors samensmelten tot een plastisch feest van kleuren en lichamen. Wordt ons gegeven wat we verlangen te zien? Waarom verveelt het ons dan?

The only way film can represent distances is by converting them into time, into duration. That is what film tries to do: convert into duration the meters that exist in reality. Ideally, I would say musical duration. Why? Because like in music, you're dealing with elements that succeed each other. You're dealing with an arrangement. If you cut a scene from a film, it would lose that operation.

De enige manier waarop film afstanden kan weergeven, is door ze om te zetten in tijd, in duur. Dat is wat film probeert: de meters uit de werkelijkheid omzetten in duur. Het liefst zou ik zeggen muzikale duur. Waarom? Omdat je net als bij muziek te maken hebt met opeenvolgende elementen. Je zit met een ordening. Als je een scène uit een film zou knippen, zou ze die werking verliezen.

On the little TV screen the person who looks at us is supposed to talk to us face to face, person to person; he or she is among us. This is where that feeling of intimacy that presides over Impromptu du dimanche comes from. But let this interlocutor stumble and lose the thread of his discourse, and the falseness of this illusory situation is brutally revealed, because we can do nothing for him and he, many kilometers away from us, finds himself alone, if not disabled, in front of soulless recording machines.

Valse improvisatie en “black-out”

Op tv hoort de persoon die ons aankijkt zich rechtstreeks tot ons te wenden, van mens tot mens; hij bevindt zich in ons midden. Dat verklaart trouwens het intieme gevoel dat van Impromptu op zondag uitgaat. Maar wanneer de spreker hapert en de draad kwijtraakt, komt het fake karakter van deze illusoire situatie plotseling aan het licht, want wij kunnen de persoon in kwestie niet helpen en hijzelf staat er helemaal alleen voor, kilometers bij ons vandaan en totaal hulpeloos tegenover zielloze machines.

Fausse improvisation et « trou de mémoire »

Sur le petit écran de la T.V., la personne qui nous regarde est censée nous parler face à face, d’homme à homme ; elle est parmi nous. D’où, du reste, le sentiment d’intimité qui préside à l’ « Impromptu » dimanche. Mais que cet interlocuteur trébuche et perde le fil de son discours, et la fausseté de cette situation illusoire nous est brutalement révélée, car nous ne pouvons rien pour lui et lui-même à des kilomètres de là se retrouve solitaire, sinon désemparé devant des machines sans âme.

A Conversation with Anna Magnani

Huddled in a doorway along the streets of Cecafumo are the cameraman, the continuity girl, the grip and his crew, all of them, I see, with resigned looks on their faces. Under a large umbrella is di Carlo, my assistant director, and some of the boys who are being filmed today; other cast members stand by the cluttered tables and dismantled equipment. It’s sort of a disaster. Someone tells me that Magnani wants to talk to me, so I go upstairs to see her in the little room a Cecafumo family is letting her stay in.

« Que le cinéma aille à sa perte, c’est le seul cinéma. Que le monde aille à sa perte, qu’il aille à sa perte, c’est la seule politique. » C’est peut-être l’affirmation la plus audacieuse que j’aie jamais entendue, tant elle est violente et dépasse les limites du cinéma. Elle émerge comme une voix dans le désert, visant personne en particulier et tout le monde à la fois.

“Dat de cinema ten onder gaat, dat is de enige cinema. Dat de wereld ten onder gaat, dat hij ten onder gaat, dat is de enige politiek.” Dit is misschien wel de meest gedurfde uitspraak die ik ben tegengekomen, omdat ze gewelddadig is en verder gaat dan het domein van de cinema. Ze verschijnt als een stem in de woestijn, gericht aan niemand en aan iedereen tegelijk.

« Que o cinema vá para o inferno, é o único cinema. Que o mundo vá para o inferno, que vá para o inferno, é a única política. » É talvez o pensamento mais radical que conheço porque é violento e extravasa o campo do cinema. Ergue-se como uma voz no deserto, dirige-se a todos e a ninguém.

“Let cinema go to its ruin, that is the only cinema. Let the world go to its ruin, let it go to its ruin, that is the only politics.” This is perhaps the boldest statement I have come across because it is violent and moves beyond the field of cinema. It emerges like a voice in the desert, aimed at no one and everyone.

Over Pasolini’s Teorema

De bezoeker heeft Pietro de ogen geopend. Het blijft onduidelijk voor wat: voor het ware leven, de liefde, het genot... Vast staat dat zijn ogen slechts werden geopend opdat hij zou zien dat hij “ziende blind” is en moet blijven, dat zo’n zien te excessief is om er over te kunnen beschikken. “Zu Blindheit über- / redete Augen”, dicht Paul Celan. Pietro werd geraakt door een “te groot” inzicht dat uiteindelijk slechts het effect heeft van een vlek die als een schaduw over zijn “normale” zien hangt.

Un entretien avec Frans van de Staak

Pourquoi ai-je pris Spinoza et pourquoi ai-je pris Poot ? Ce sont des personnages qui, bien que solitaires, étaient néanmoins très tournés vers leurs milieux. Et je crois que peut-être cela est en moi un thème. Chez Spinoza comme chez Poot, il s’agit d’une sorte de désir... et c’est ainsi pour moi... même si je trouve un peu ennuyeux de le dire. Oui, cela est vraiment le seul mot. Désir, c’est le désir qui me pousse. Pas la colère, mais cependant aussi une émotion très forte.

A Conversation with Frans van de Staak

Why did I choose Spinoza and why did I choose Poot? In fact, because they forced themselves to pay full attention to their environments, although they were lonely. And perhaps, I guess, this is my own theme. For Poot as well as for Spinoza it is desire of some kind… and the same holds for myself; although it is a little bit embarrassing for me to say this. Alright, actually, this is the proper word. Desire, I am driven by desire, not by anger, but by a very strong emotion indeed.

Een gesprek met Frans van de Staak

Waarom heb ik Spinoza en waarom heb ik Poot genomen? Toch omdat het figuren zijn die, ondanks dat ze alleen waren, toch ontzettend op hun omgeving gericht waren. En ik geloof dat dat misschien bij een thema is. Zowel bij Spinoza als bij Poot is het een soort verlangen… en dat is bij mij ook zo – hoewel ik het een beetje vervelend vind om te zeggen. Ja, dat is eigenlijk het enige woord. Verlangen, verlangen dat mij drijft. Geen kwaadheid, maar toch ook een sterke emotie.

Beschouwingen over het commentaar op televisie

Of het tv-commentaar nu geïmproviseerd, deels geïmproviseerd of voorbereid is, het moet aan een aantal eisen voldoen. Als het erom gaat een documentairefilm toe te lichten, kan de commentator een voorbeeld nemen aan de soberheid die de filmkunst mettertijd heeft verworven. Het commentaar moet voorts competent en efficiënt zijn. Zo kan men bijvoorbeeld beter de naam van de dieren vermelden in plaats van enthousiast over hun vacht of hun gedaante te praten, wat iedereen gewoon kan zien.

Réflexions sur le commentaire à la T.V.

Improvisé, semi-improvisé ou préparé, le commentaire de T.V. doit répondre à certaines exigences. S’agissant d’accompagner des films à caractère documentaire, il peut s’inspirer d’abord avec profit de la sobriété acquise au cinéma. lI doit aussi être compétent et efficace, donner par exemple le nom des animaux, au lieu de s’extasier sur leur pelage ou leur allure, que tout le monde peut voir.

Whether improvised, semi-improvised, or carefully rehearsed, TV commentary should respond to certain requirements. Commentaries that accompany films of a documentary nature ought to be inspired by the restraint that has been adopted by cinema. They should also be competent and effective, for example, providing the names of the animals instead of going on ecstatically about their fur or their speed, which everyone can see.

Man expresses himself above all through his action – not meant in a purely pragmatic way – because it is in this way that he modifies reality and leaves his spiritual imprint on it. But this action lacks unity, or meaning, as long as it remains incomplete. [...] So long as I’m not dead, no one will be able to guarantee he truly knows me, that is, be able to give meaning to my actions, which, as linguistic moments, are therefore indecipherable.

I never decided to become a documentary filmmaker; that is to say, to camp once and for all inside a given space. Besides, I hate that term: documentary filmmaker. It helps to erect a boundary around a genre that has never ceased to evolve and whose porosity, shifting contours, and almost consanguine ties with the genre it is always set against, fiction, are on the contrary well known. For it is indeed true that images are less faithful to “reality” than to the intentions of those who produce them.

Je n’ai jamais décidé de devenir documentariste, c’est-à-dire de camper une fois pour toutes à l’intérieur d’un espace donné. D’ailleurs je déteste ce mot : documentariste. Il contribue à dresser une frontière autour d’un genre qui n’a jamais cessé d’évoluer et dont chacun connaît au contraire la porosité, la variabilité des tracés, les liens presque consanguins qu’il entretient avec celui qu’on lui oppose toujours, celui de la fiction. Tant il est vrai que les images sont moins fidèles au « réel » qu’aux intentions de ceux qui les produisent.

« Déshabillez-vous les chaussures », me glisse Lim Ji-yoon, ma jeune interprète coréenne, avant de me faire entrer dans un petit salon du Dongsoong Art Center. C’est donc là, en chaussettes, assis en tailleur, que je vais passer une grande partie de mon séjour à Séoul, à répondre aux questions des journalistes. On nous sert du thé vert, tandis que ma première interlocutrice me tend sa carte de visite et branche son mini-disc : « Dans votre film, les premières images de l’école montrent des tortues qui se promènent dans la classe. Quel sens vouliez-vous donner à ces plans ? »

Over Showgirls (1995) van Paul Verhoeven

Ongeveer dertig jaar na datum is Showgirls – volgens Verhoevens redenering – des te meer gedoemd om te mislukken. De film is een project waarin “aanstootgevend” naakt als instrument gebruikt wordt om het publiek indirect met een zedenschets te confronteren, terwijl dat publiek steeds vaker vraagt om een behapbare en “veilige” inhoud en om een filmtekst die ook bij een oppervlakkige interpretatie “bevredigend” blijft.

Marva Nabili’s The Sealed Soil (1977)

The Sealed Soil is a mesmerizing exploration of stasis, containment, domestic anxiety, and the quiet possibility of salvation. Through long takes and composed stillness, Nabili’s film invites viewers to experience the materiality of cinema – its temporal weight, meditative rhythm, and aesthetic force – giving profound meaning to the notion of women’s cinema. A work of rare beauty and quiet defiance, The Sealed Soil stands as a luminous gem in the canon of Iranian classical and arthouse cinema – a testament to the enduring power of feminist filmmaking.

It was by inviting us to compare Le grand bleu [The Big Blue] and Palombella rossa [Red Wood Pigeon] that Serge Daney concluded his 1980s[.] […] [W]hile aphasic, “self-legitimatising” individuals retreat into Bessonian depth, a people “sick with language” forms on the Morettian surface. […] For Daney, “Red Wood Pigeon is a great film and Nanni Moretti the most precious of filmmakers.”

De toutes les épithètes caustiques déployées par Cahiers du cinéma au cours de ses nombreuses disputes critiques, peut-être la plus archétypale est celle apparue à la fin des années 70 : « cinéma filmé ». Une expression dont le sens peut être presque instinctivement deviné par le lecteur. De même que des films adaptés de pièces de théâtre de manière banale, sans prendre en compte les exigences esthétiques particulières au cinéma, sont étiquetés avec dédain comme « théâtre filmé », il existe aussi des films qui donnent cette même impression de recyclage et de manque d’originalité — mais à l’égard du cinéma lui-même.

En tant que critique d’un temps désormais révolu, les textes de Daney nous ont situés dans le rôle du spectateur — qui est aussi, à la fois, celui du critique — un rôle qui existe sous deux formes : « sous forme de corps inerte parmi les autres et sous forme de regard vif parmi les plans ». Son amour des interstices justifiait l’existence de la critique, et c’est dans ce geste imaginatif de Daney que nous essayons de nous situer, réclamant le temps pour qu’un film mûrisse dans le corps, par la stupeur, le choc ou la tendresse, et invoquant une forme d’écriture critique prête à éclairer.

The principle of insufficiency remains at the heart of cinema, even at a time when auteurs too readily drape themselves in the autonomy of “It’s enough for me.” [...] This solitude gives films a unique tone, a muted rage or a desolate music. How far can a filmmaker go in solitude without losing not only the audience, but cinema?

Un critique œuvre caché – dans l’ombre (de la salle, des films) et la forêt (des revues) – et Serge Daney ne fait pas exception. Que sa trajectoire soit finalement devenue exemplaire, que sa figure soit entrée dans la lumière progressive de la reconnaissance publique a modifié aussi bien la lecture de ses textes que leur adresse, en déterminant le ton et le style. Une constante, néanmoins : la vitesse.

A critic operates in the shadows (of the screening room, of films) and in the forest (of journals), and Serge Daney was no exception to the rule. The fact that his career is now viewed as exemplary, and that he has increasingly come to enjoy the limelight, has altered the reading of his texts and — during his lifetime — also their address, influencing their tone and style. One constant remained throughout, however: speed.

C’est en nous invitant à comparer Le grand blue et Palombella rossa que Serge Daney conclut ses années 80. [...] Dans la profondeur bessonienne s’isolent des individus aphasiques “auto-légitimés”, alors qu’à la surface morettienne se forme un peuple “malade du langage”. [...] Pour Daney, Palombella rossa est un grand film et Nanni Moretti le plus précieux des cinéastes.

À quoi ressemble la voix de Daney ? Bien que je m’y sois plongée pendant des années, je n’ai jamais essayé de décrire la voix de Daney. La traduction se rapproche davantage d’une pratique d’écoute que de la description, ou de l’intellectualisation, et traduire La Maison cinéma et le monde a été une pratique consistant à traquer une pluralité de voix, à suivre la cadence confiante et saccadée de la pensée de Daney alors qu’elle brûle à travers toutes sortes de sujets et de formes avec une aisance presque incroyable.

Le voyage n’est donc qu’à peine un thème. Daney, de toute façon, thématise peu. Sa pensée procède par leitmotivs, voire par des obsessions qui lui sont personnelles et ne craignent pas de le rester. Aussi ne doit-on pas s’étonner si, de tous les articles qu’il a publiés – autour de deux mille – un seul inclut le mot « voyage » dans son titre. Ni si, dans cet article, il est question de tout sauf de voyage.

What does Daney sound like? Although I’ve spent years immersed in it, I haven’t yet tried to describe Serge Daney’s voice. Translation is more akin to listening than it is to description, or even intellectualisation, and translating The Cinema House and the World has been a practice of tracking a plurality of voices, of following the confident, clipped gait of Daney’s thought as it burns fast through a variety of subjects and forms with almost impossible ease.

As a critic of a time now lost, Daney’s texts situated us in the role of the spectator – which in turn is also the role of the critic – who exists in two ways: “as an inert body among others and as a vivid gaze between shots”. His love for the interstices justified the existence of criticism, and it is in this imaginative gesture of Daney’s that we try to situate ourselves, demanding time for a film to mature in the body, through stupor, shock or tenderness, and invoking a form of critical writing ready to illuminate.

Introduction à ‘Serge Daney et la promesse du cinéma’

À peine quelques mois avant sa mort, en réponse à une question de Régis Debray sur « les images qui vous ont regardé » lorsqu’il était enfant, Daney est catégorique : « [L]a première image qui a compté pour moi, et l’image presque définitive, ce n’est pas une image de cinéma, c’est l’atlas de géographie . » Enfant, il était en effet captivé par les cartes du monde, représentant un univers bien plus vaste que le milieu parisien borné d’après-guerre dans lequel il grandissait. Pour Daney, elles portaient la promesse de devenir « citoyen du monde » — une promesse qu’il estimait avoir largement réalisée à travers sa vie dans le cinéma, déclarant à Debray : « J’en ai vécu de cette carte du monde . »

Introduction to ‘Serge Daney and the Promise of Cinema’

Just months before his death, in response to a question of Régis Debray about the images “that looked at you when you were a child”, Daney was unequivocal: “the first image that counted for me, almost the definitive image, wasn’t a cinema image, it was the geography atlas”. As a child, he was indeed captivated by world maps, suggesting a universe far vaster than the narrow confines of his post-war Parisian surroundings. For Daney, they held the promise of becoming “a citizen of the world” — a promise he later believed he had largely fulfilled through his life in cinema, telling Debray: “I’ve lived from that world map”.

Travel is barely a theme, then. In any case, Daney rarely thematises. His thought proceeds by leitmotifs — or even through personal obsessions that are unafraid to remain so. It’s hardly surprising then that, of the many articles he published — around two thousand — only one includes the word “travel” in its title. Nor that, in that article, the one thing that is never discussed is travel.

Le principe de non-suffisance reste au cœur du cinéma, même à l’époque où les auteurs se drapent trop facilement dans l’autonomie du « Ça me suffit ». […] Cette solitude confère aux films une tonalité propre, une rage sourde ou une musique désolée. Jusqu’où un cinéaste peut-il aller dans la solitude sans perdre non seulement le public, mais le cinéma ?

Daney s’oppose à toute image qui entrave ou perturbe ce passage, qu’il s’agisse du visuel, de la pornographie, de la télévision, de la publicité, du scénario, des dessins animés ou du maniérisme. Chacune empêche un passage « entre » deux éléments (champs et contre-champs, champs et hors-champs, deux états, deux images, deux corps, l’intérieur et l’extérieur des personnages, etc.). « La crise du cinéma, c’est la crise du “entre”. »

Of all the caustic epithets deployed by Cahiers du cinéma during its many critical disputes, perhaps the most archetypal is a term that emerged in the late 1970s: “filmed cinema”. Its meaning can be almost instinctively divined by the reader. Just as films that are adapted from plays in a pedestrian manner, without any thought given to the specific aesthetic demands of the cinema, are derisively dubbed “filmed theatre”, so too there are films that give this same impression of being recycled and derivative, but with respect to the cinema itself.

Daney was opposed to every image that hindered or perturbed this passage, whether spectacular images, pornography, television, advertising, the script, cartoons, or mannerism. Each blocked a passage “between” two elements (the shot and the counter-shot, on-screen and off-screen, two states, two images, two bodies, the interior and exterior of characters, etc.). “The crisis of cinema is the crisis of the ‘between’”, he wrote.

Six Moments

Frieda Grafe’s thinking was only accessible to those who read (and hear) German. Only recently, her articles and essays have started to be translated into English and other languages. It will be exciting to see what happens when new readers encounter her thoughts. Some things will be lost in translation, other aspects will come to the fore. Different sounds and rhythms will meet different ears. It’s always a risk, but a risk worth taking.

From 1970 to 1986, the daily Süddeutsche Zeitung published Frieda Grafe’s Filmtips, short commentaries on Munich’s film offerings, often just one sentence per film, every week. Sabzian selected and translated eight of them.

The awareness of programme makers and especially of television critics about the medium they are dealing with, is still very low. Television blindly exploits what cinema, theatre, politics and other media produce. What could television be? No one is more reluctant to answer this question than television. Unproductive in its own right, it only appropriates film history in order to exploit and rehash it.

À propos de deux expositions sur Jean-Luc Godard

Il était une fois un garçon surnommé « IAM ». Élève du Collège de Nyon, doué en mathématiques et athlétique, ce jeune homme reçut ce surnom au ton quelque peu spéculatif, dérivé probablement de l’anglais « I am ». Les raisons exactes de ce choix demeurent incertaines, mais il semble clair que son propriétaire l’appréciait. En effet, après avoir obtenu son diplôme d’études secondaires en 1946 et intégré le lycée Buffon à Paris, il commença à signer fièrement ses premières œuvres artistiques sous le nom de « IAM », à la fin de son adolescence. Ce jeune homme n’était autre que Jean-Luc Godard, le cinéaste qui devint une figure emblématique de la Nouvelle Vague[.]

Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal

Fielder is both the instigator and the mediator of his chaos. In this way, he resembles a traditional ethnographer navigating the landscape of reality television, portraying society as a whole, and people, as acting, feeling and fundamentally uncertain beings, as something exotic. His awkwardness can almost be read as a kind of scientific attitude. He doesn’t observe in order to explain but to make the impossibility of total control palpable.

Nathan Fielders The Rehearsal

Fielder is tegelijk aanstichter en bemiddelaar van zijn chaos. Op die manier heeft hij iets weg van een klassieke etnoloog die zich in het landschap van de reality-tv voortbeweegt, waardoor hij de samenleving als geheel en mensen als handelende, voelende en fundamenteel onzekere wezens in het bijzonder als iets exotisch neerzet. Zijn ongemakkelijkheid kan je daarbij bijna zien als een wetenschappelijke attitude. Hij observeert niet om te verklaren, maar om de onmogelijkheid van volledige controle tastbaar te maken.

Qu’on puisse raisonnablement aujourd’hui se poser une telle question et qu iI faille raisonner pour y faire une réponse optimiste suffirait déjà à justifier l’étonnement et la méditation.

Dat die vraag vandaag de dag bij me opkomt en ik moet nadenken om een hoopvol antwoord te formuleren, rechtvaardigt al meteen de verbazing en reflectie die ze oproept.

The fact that one can reasonably ask oneself such a question today, and that it requires some thinking through to come to an optimistic answer, should be enough to justify astonishment and musing.