Spike Lee’s American Didactics

As the twentieth century draws to a close, absolute evil (racism, rape) and absolute difference (racial and sexual) haunt our fantasies. We want to eliminate difference because it seems to be the sole cause of crime. Our many good intentions have facilitated an oppressive hypocrisy. Indeed, to many, the mere pronouncing of difference seems to create inequality. Hence the inability to name things soberly; hence also our liberating laughter at the verbal obscenities and aggression of so many comic and lucid films. With regard to difference, we have become so prudish that a daring subculture of verbal release has developed. Such is the case in the films of Blier and in Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever (his fourth film, but the first one I saw).

We spontaneously think difference as being different from the other party, but it’s also the experience of one’s own boundary, of the outlines of one’s own territory and ability. Difference is perhaps less about defining than about delineating, seeing a border post where negotiations are needed, visas are checked, a new language tried stuttering and blushing. The other is the one who sees me ashamed as other. Spike Lee makes us undergo this sensation. Concerned and curious, the (white) spectator wonders how he will be portrayed, what kind of gaze will be cast on him. Will it be a caricature?

Jungle Fever is a strange, grandiose and disappointing American film! Once again, it shows how America’s powerful, coercive story-industry deals exclusively in stereotypes. Making diversity visible and recognisable has always been its essential function and source of inexhaustibility. In the film, we do see the symptoms, the signals of diversity, but not the difference. We enjoy the burlesque clashes between rich and poor, male and female, the civilised and the savage, the conservative and the liberal. But those burlesque clashes are a very weak illustration of difference. After all, where there are clashes, both sides see each other, touch each other’s ground, observe and discover each other’s strengths and capabilities. In reality, difference leads to naked indifference. The most terrible difference is the absence of friction and collision, or covert, perverse friction and collision. That is precisely what Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever is not about; difference becomes a driving force in a predictable, recognisable and, for all that, very charming love story. Everything can be named here – both by the characters themselves and by the director. Despite all the four-letter words, the violence and failure, it remains a fairy-tale story from which the characters learned something and in which the conflicts did not punch a hole in life. The latter only happened to some fringe characters – addicts mostly, whom Lee evokes in a stylised and demagogic fashion. The negative is never dull and banal in American films, the way it is, I fear, in reality.

Conservatism

No alternative film culture appears here. Spike Lee illustrates the lasting vitality (and limitation) of American cinema, which has always included the management of diversity. This is the basis of its “conservatism”, the basis also of its illusions – but it is above all the basis of its social creativity, its immense cultural role. American cinema is effective in its advice.

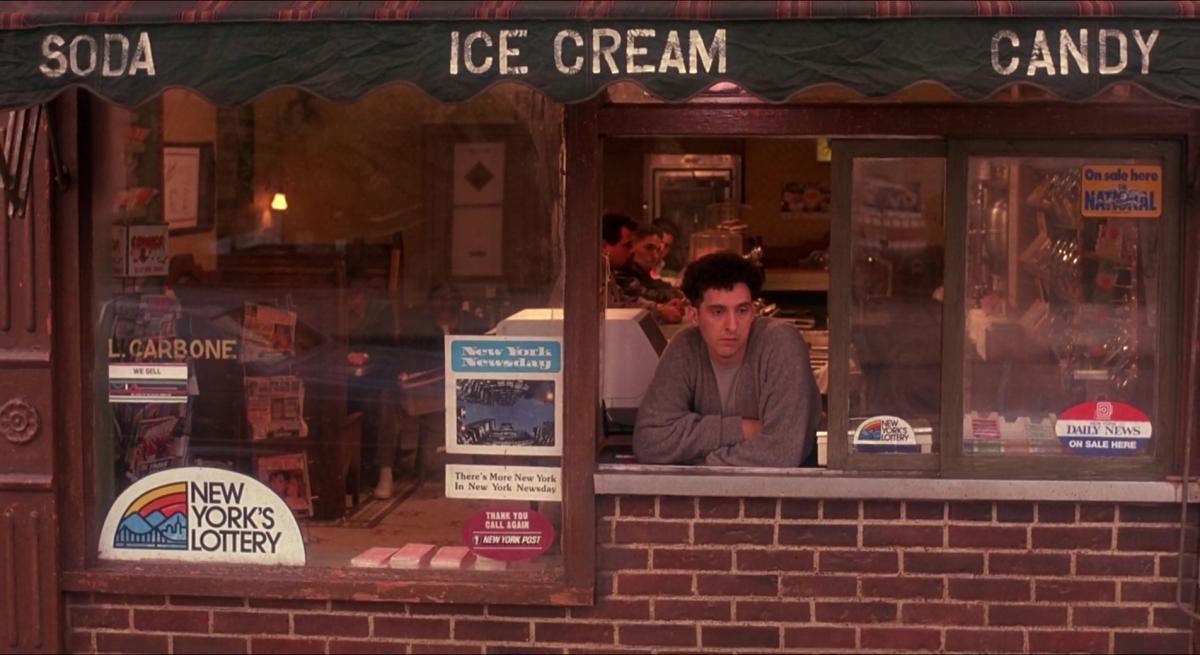

We in Europe have a very different perspective on racial difference. Until recently, it was more a matter of principle than an everyday problem of encounters, glances, sounds and colours. For this very reason, we automatically smile a bit derisively at the concrete encounters, neighbours’ quarrels and brawls in bars which racial difference seems to be limited to in American films. But these things are also very beautiful. One of the strongest roles in Jungle Fever is Paulie, who works in a bar [TN: it’s actually a candy store], which is also a tobacco and newspaper shop with both Italian and Black customers. With his fragile minor tone, his limitations and his courage, his principles and failure to live up to them, he is the marvellous mirror image of the much more predictable main plot. Could you ever think of such a figure in Europe? Such a moving illustration of good will, of clear principles and nuanced judgement? He is the ideal American: at once simple and complex.

We in Europe lack that pragmatic basis; we absolutise difference in an ideology. Surprised and incredulous, we watch the American spectacle: could it be that simple? And perhaps that’s when we come to see the beauty of the film, of its actors, of its brittle sound and scene construction, rhythm and mise-en-scène. Could this film culture be so alive because it not only sees problems but also recognises solutions, and is thus happy no matter what? It’s that happiness (beyond any ideology) that Spike Lee shows too.

Images from Jungle Fever (Spike Lee, 1991)

This text originally appeared in Kunst & Cultuur 24, October 1991.

Many thanks to Reinhilde Weyns and Bart Meuleman

With support from LUCA School of Arts, LUCA.breakoutproject