Punk, the Bedroom, Adolescence

A Conversation with Pedro Costa on In Vanda’s Room

The text below is a translation of the first chapter of the book included in the French DVD edition Dans la chambre de vanda, published in 2008 by Capricci, and edited by Cyril Neyrat. The book consists of a long conversation between Neyrat and Pedro Costa on his film In Vanda’s Room and is accompanied by documents, images, and collages by Pedro Costa and Andy Rector.

![(1) No quarto da Vanda [In Vanda’s Room] (Pedro Costa, 2000) (1) No quarto da Vanda [In Vanda’s Room] (Pedro Costa, 2000)](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Vanda_03%20kopie.jpeg)

Opening

But at that time will be praised

Those who sat on the bare ground to write

Those who sat among the lowly

Those who sat with the fighters.

Those who reported the sufferings of the lowly

Those who reported the deeds of the fighters

With art. In the noble words

Formerly reserved

For the adulation of kings.

Bertold Brecht, ‘Literature Will Be Scrutinised’

In his film In Vanda’s Room, Pedro Costa recounts the misfortunes and deeds of the “other half” of this world. He has done so in the noble language of a realist tradition of cinematic storytelling inaugurated by Griffith at the beginning of the last century. Eight years after its release, the status and aura of this film have only grown. On the scale of a work: discovering Vanda and the Fontainhas district, Costa found his intimate need, his concern and his method. In Vanda’s Room opened up a path that he has not finished tracing.

On the scale of an art: cinema was reborn, perhaps most recently, in a shanty town in Lisbon, within the walls of a green room. Costa was the first to place DV on the tripod of Ozu and Straub, to extract the light of Tourneur to reanimate on the screen the primitive energy of cinema: the work of death and the play of life, the words and flesh of the nameless, the beauty offered to the infamous by the art of matching editing points, vanishing lines and shots of light.

A work of this kind will retain its mysteries, but this book aims to take us as close as possible to the secret of its beauty. First, through the voice of Pedro Costa who, in a long interview, opens the doors of his studio like few filmmakers before him, recounts the joys and doubts of making the film, the enthusiasms and pains of an experience that changed him: why this leap into the void, what working method is invented there, with which old does the new reconnect? Then there’s Andy Rector, who, in the discontinuous movement of a collage sent from as far away as Fontainhas – from California where he lives and works – was able, “between analysis and reverie”, to touch the most sensitive chords of In Vanda’s Room. The same search drives the film, the interview and the collage: that of a shared space, of sensitive solidarity over time.

Cyril Neyrat

Sintra, Portugal, 13-15 August 2007

Sintra, some fifteen kilometres from Lisbon, Portugal’s oldest city, clings to a ridge that separates the hinterland from the Atlantic coast. The mountainous barrier creates a strange, almost tropical microclimate. On the heights of the city, on the edge of a dark forest as far as the eye can see, Pedro Costa lives in the former home of Hans Christian Andersen. Fifty metres away, on the pavement opposite, lived Thomas Bernhardt. On the mountain ridge, you can see the ruins of a fortified castle, a reminder of the presence of the Moors. A timeless enclave, far from the hustle and bustle of the capital, Sintra is a haunted place, populated by legends and the ghosts of past glories. The forest has always been home to a Brazilian voodoo cult known as “macumba”. Night has fallen, and lights pierce the dark mass of trees: “That’s Edie Sedgwick’s sister’s house.” Started in the evening, the conversation lasted all day the following day.

Punk, the Bedroom, Adolescence

Cyril Neyrat: What is the origin of In Vanda’s Room?

Pedro Costa: Considering the film as it is now, the form it has, it can only come from things like tiredness and disgust. Not from a search. Nor from a rupture, in the sense of a film that you make by saying to yourself: “I’ve got an idea, I’m going to make a film with this form, in this environment.” It surely comes from the years before cinema, from something other than cinema. It doesn’t come from childhood but surely from adolescence, in other words from the bedroom. It’s banal, poetically banal, all teenagers understand this desire to be a little locked up, to brood over their thoughts, not to speak, to invent, to dream, to take drugs. Poetry, Pessoa, Rimbaud, rock, friendships, dreams of changing things or changing nothing at all. Everything that makes up a teenager’s bedroom. It must have come from there, from what I wasn’t able to say. The films I’d made up to Vanda had taken some laborious detours. I felt a bit distant from myself – even if I already felt that you shouldn’t make too many films about yourself, it already disgusted me. All those filmmakers and films from the eighties, European films, art house films, French, Hungarian, Greek, Portuguese, with their arms swinging to the music of Schubert.

Did you think they were too navel-gazing?

And how! I was shown these films – not all the time, but sometimes – at film school. When I enrolled in 1979, there was a bit of that. Fortunately, my insolence saved me. It was a time when I was reading a lot of Vertov’s Journals and applying his postulate to the letter: “Do not touch bad films with your eyes.” And also partly because I’d been through a kind of collective. A bunch of friends, in rooms. We were more into music, which requires a different kind of energy. We weren’t intellectuals. Vanda stems a lot from music, in other words from this deep belief in an energy that meant that for me, at twenty years old, the Sex Pistols or Wire were on a par with Straub and Godard, or Ford and Tourneur, the classics. But I wasn’t yet convinced, I hadn’t yet made up my mind. I hadn’t said: “It’s Straub rather than Wire.”

Were you already familiar with Straub’s films at the time? Were you exposed to both at the same time, punk and the Straubs?

Yes, it was luck. In fact, I think Portugal is a country where the Straubs were seen, although they weren’t popular either. I remember watching The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach on television when I was young. In the winter, on Christmas, I think. They played it almost like a holiday film. And João Bénard da Costa always showed their films at the Cinemateca. The form of Vanda, freed from a certain weight compared to my previous films, freed also from the films of others, perhaps comes from this prehistory. I think that today, but it took three feature films, a lot of watched films, reading and writing about cinema. No novels, no literature – I’m not a great reader, I always read the same things. In short, I think it clearly comes from something sonic, musical, from that energy, from that period you could call “punk”. Including making a film almost on my own, setting off like that, stubborn, and doing something that was impossible, even technically. For me, who had filmed in 35 mm with crews, and therefore had a more or less planned future in the “profession”, it was quite crazy. I said to myself: “I don’t know what I’m doing, whether it can work technically”, and that I would look for people to help me. But technique isn’t what we're told – something I’d felt since my Godard-Straub apprenticeship. It’s not about mise en scène, it’s really about the means, the organisation, the human relationships, the way you make a space your own. I felt that the solitude of this work was not an oddity, that it could be done with people, that there was a place for this kind of work. If I was really alone, it was also because my years as an assistant and the shooting of my films had left me very disgusted. I’d seen crimes, massacres and minor failures. Directors panicking, suffering. The horrible system, which everyone knows and which is always the same; “we have to do it, we have to shoot it, we don’t have the money or the time”, with people who are not interested. There was a clash, a very clear one: a film has to be of interest to the people who make it and then see it. So getting involved with people who aren’t interested in the work they do, or apparently very little...

![(3) No quarto da Vanda [In Vanda’s Room] (Pedro Costa, 2000) (3) No quarto da Vanda [In Vanda’s Room] (Pedro Costa, 2000)](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Vanda_02_0.jpg)

I’m totally obsessive, totally complicit, even with a guy who’s completely mad, who says things I don’t understand, but who’s there in body and soul. I can’t pretend, so I couldn’t see what to do with these people next to me, behind the camera. I always felt that something was pretending, not so much in front of the camera as behind it. In front, I wasn’t thinking about it yet. The fiction was behind the scenes, the set-ups, the staging, the intrigues... There was too much fiction behind the camera and maybe not enough in front of it, or not the right kind, or badly set up. I believed in myself a little, I knew I had things to say, places to meet, people. I believed in that. But behind the camera, it was really a problem.

Do you see your first three films as a detour towards In Vanda’s Room?

Not a detour, more a path, little by little, slowly. But that’s almost true of all first films. I’m not comparing myself; I think that my films, in general, are much weaker than those of the people I could mention now. Godard, who took seventy years, Straub would say, to find himself.

Straub says that about Godard?

No, he says it about himself... I think I prefer what Godard is doing now. Obviously, there’s the beauty of Une femme est une femme, Vivre sa vie, Le Mépris, Pierrot le fou, a thousand films he’s made. But to get to the core of what he was really after, he had to go through all the different stages, testing, making those Hollywood bluffs, the stars. You grow old filming, you know.

Including the experiments with video.

For him, I think it really begins a little earlier. I’m very interested, fascinated, and more than that, by the period of the Dziga Vertov group. I think that’s where it all began. Made in USA, Deux ou trois choses, La chinoise, the accident, the disappearance, and then this return to another kind of home-made cinema, DIY, almost amateurish, even a little bland. Numéro deux is a film I love, quite brutal, there are no two like it. I’m not saying that just anyone can make Le Mépris or Pierrot le fou. The core of Godard, which is incomparable, I can see it happening with Numéro deux, and even before that, in the films with Gorin. Then all the work on video, and even the 35 mm films that were a complete failure, Hélas pour moi, For Ever Mozart or Sauve qui peut. I think he was made for very imperfect things, but that was his truth, and not just the great form of Le Mépris. It’s quite a movement from Le Mépris to Ici et ailleurs, isn’t it?

Not a detour, but a path...

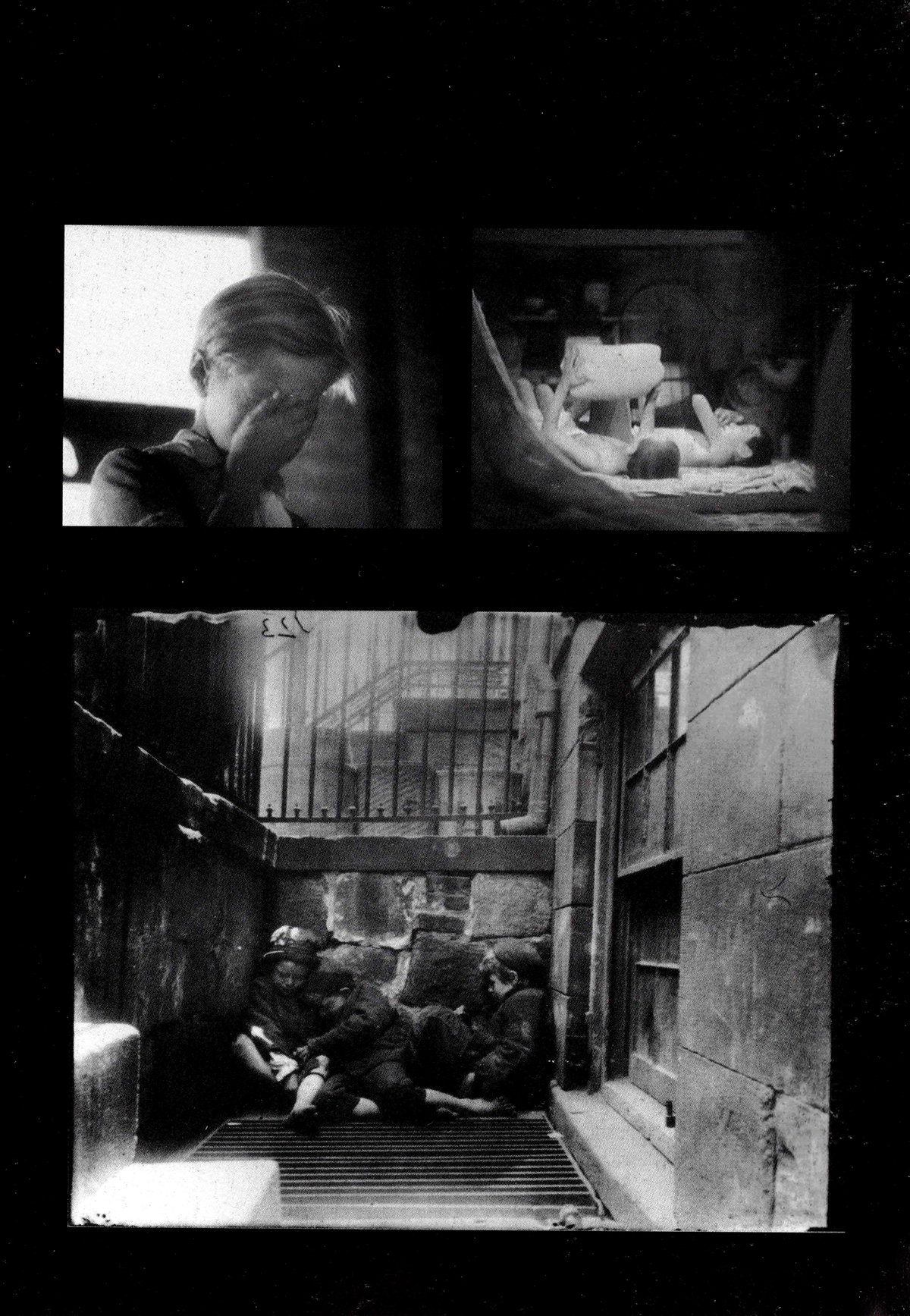

Yes, like Godard, it takes years to find yourself, to break out of yourself. It’s a matter of conviction, or rather a lack of conviction that is disguised by an over-emphasis on form. Something Danièle and Jean-Marie have never suffered from, which brings them closer to another time, another cinema, the classics. Even if it’s not very clear, you know you’re going to be revolving around something all your life, you can feel it, it’s a question of limits. And when you break out of it, you feel you’re taking a wrong step. To find it, you had to go through a first film, which is like all first films: very cinephile, very young, confessional, and fantasised. Then a second film, lost, as second films often are, with very special moments because there was a kind of call to something outside myself. I didn’t know what it was yet, but there was this fear of facing a stranger who spoke a different language. I told myself that the best way to face this fear head on was to go straight there: to the volcano, to the dark. An adventure story. And then the descent begins. The film had lost its way, and I had the feeling with Casa de Lava that we were feeling our way around. In fact, it’s not bad to feel that way in the second film. We were doing everything correctly, all the movements, all the set-ups, the team was working, and I could see that it was happening behind me. Reality was slipping away. It was slipping away everywhere and so I started to boycott the film, certainly against the producer, but above all against myself. Casa de Lava is completely boycotted, I did it almost against myself. On the one hand there was the script – even if it wasn’t really coherent – and on the other hand the situation: “This is what I really feel, this is what we’re doing here.” The result is this lost back and forth, which fits in well with the story of a lost girl who can’t find the words, the emotion or the path... Around me, I saw these people who were a bit needy, the Cape Verdeans, who acted as extras, who helped out; sometimes they were hired to cook. I wanted to make the film with them, and almost forget about the crew. I felt capable of taking the 35 mm camera, the sound, leaving with the equipment and shooting alone. And at the end of the shoot, because we’d all learnt a bit of Creole, the people of the village gave me and several members of the crew letters, messages, gifts, packets of coffee and tobacco for the families, fathers, mothers, sons and children who lived here, in Lisbon, as immigrants, especially in Fontainhas or nearby. So I went to the neighbourhood as the postman. It must have been very strange to see a guy like me arrive, mumbling a bit of Creole and saying, “Here, madam, there’s your son who sent you this, he’s fine, he was taking part in a film I made.” And of course, each time, we’d have a drink with these people, we’d eat, and of course we’d have to come back tomorrow “because there’s a party, because you have to meet my husband and we’re going to do something extraordinary”. With a friend, Joaquim Carvalho, who also worked on Colossal Youth, and who had a particular taste for this kind of things, we started coming here, and coming back. I was enchanted by the colours, the sounds, everything that was visual and sonorous, it was already a bit outside the city, on the fringes of society. I don’t really like cities; I don’t feel very comfortable in them. I think it comes from the western. It's often in westerns that you’re most locked into a capsule of silence and solitude. Or from Straub and Godard, in the sense that you can work at home better than anywhere else, you can make a film with a lamp, a sofa and a bunch of flowers.

Don’t you appreciate the kind of reality imposed by the city?

I don’t know, I’d have to think about it. It must be my dream to self-produce films outside the centres of power. It must also be my taste for the bedroom, for confinement, which is immediate in this neighbourhood. The films I've made here are confined and want to be confined. Indoor films. I had to discover that too, that I'm made to film in rooms, doors, corridors, even if they're outside. The neighbourhood offered me a magnificent space to think about. And thinking about space is one of the foundations of cinema. In Vanda, in Ossos already, but without thinking about it, just out of sheer fascination, you don't really know whether you're in someone's house, in everyone's house, or whether that house, that living room, that bedroom, isn't more of a square or a forum, an agora, a place where people pass through to say lots of things or hide from each other.

Is that what struck you when you first discovered the area?

It wasn’t obvious, it was more of a poetic feeling. You think about it, you see things in films, you read books, you hear music. It’s also all that punk energy, which apparently wants to expand, but which is also a force of destruction, and of yourself rather than others. Punk had this savagery, which in the beginning was not an affirmed policy, but pure “force”. In this connection, I must mention someone important to me: John Lydon. I've always followed him and everything he says seems very obvious and very funny, especially today. He already knew that punk was going to kill fragile people like Sid Vicious, that in fact that's what it was made for, so it was nasty. In other words, you don't know where you're going, but you’ve got to go and soldiers will fall. But the force was mainly directed against themselves: they had to blow up the romantic bedroom. It was an impossible room in an impossible world that had to be blown up. Some were sacrificed and others, like him today, became a kind of wise buffoon who lives off it, who is bitter, but who did it with a clear conscience. I think that Lydon is the only one, not only in his attitude, but also in a sensual way, who knew from the beginning all the steps to take, who refused all the bullshit.

Maybe that’s why he was the only one to go so frankly and fully into the money and showbiz side of things.

And he made PiL, one of the most important things in music. I can’t think of an equivalent, apart from Wire. I’m not talking about Webern, of course, because at the time, for people who are now forty and over, that was as far as they could go. Doing something post-Webern seemed impossible. Some people around us were doing jazz, Coltrane, and they’re still doing it today. It seemed absurd, even more so to embark on a serious project: studying music in depth, starting from the beginning to get to Webern, Stockhausen, Nono. I’m not saying it wasn’t good, because we listened to that too, equally. Maybe not equally every day, but we often listened to Nono and Berio, a bit stoned, I admit. But yes, Stravinsky and Schoenberg were often on, but it seemed impossible to go in that direction given what we were going through. We’d open the window and say to ourselves: “This is going to be shit, it’s going to be a show-off, we’ll never be able to do any better”. It seemed too high up. I’m not saying that Straub or Godard were too high up, because I didn’t know much about them yet. Godard was all about girls, meeting people, by chance, café life... Straub wasn’t, there was something serious, political, moral about it, that no one came close to, except me, and that touched my closed-off, solitary side. All that to say: there’s nothing in common between what Jean-Marie, Danièle, the people who started out in the sixties, and those who started out like me. But what hasn’t changed is the loneliness. Another thing that counted was that we were living here in a post-revolutionary period. We were the sons of petty and middle-class bourgeois, from Lisbon or the surrounding area, and very quickly, three years after 25 April, we realised that things were lost. So we got into some very radical stuff, very much against political commitment. Lots of people became situationists, anarchists or whatever. There was very quickly a rejection of many directions and an appeal to others, which perhaps closed doors to certain music or literature, certain cinema. There aren’t many filmmakers, writers or musicians in my generation. Poets perhaps... But today, I say to myself that I was incredibly lucky: to have been able to experience, in the prime of my life, the revolution, the discovery of politics, the enthusiasm of the street, and, at the same time, the discovery of Straub, Godard, Wire, Clash, poetry, Ozu, Ford... These are my gems for all time. Numéro deux, the Wire and PiL albums, all Danièle and Jean-Marie’s films, the first Ozu and Ford films seen thanks to João Bénard da Costa, Stars in my Crown...

And of course, above all, the encounter with António Reis, my teacher at school and a very dear friend who first proved my insolence right. Seeing Trás-os-Montes reconciled me with my country and my language. For the first time in my life, I felt at home here, I wanted to live and work here. It’s only now that I recognise its importance, its calming power and its seriousness in these urgent and tense times. António, who used to say: “You have to risk your life with every shot.”

In the face of this fatigue, this disgust with politics, was punk the only voice?

Punk killed itself very quickly, but the disgust remained. Now I’m thinking about it, but that takes years. The approach to this neighbourhood, apparently by chance, through the artifice of the “postman”, this slightly romantic thing, was like a stroke of fate, a key. Encountering this neighbourhood meant meeting “the other half”, and meeting her face to face. But it takes days, months and years for it to become more than just “the other half”. That’s why I stay there. It was sheer misery. Rats, people living in complete despair. It wasn't at all the romanticism of youth that I’d gone through, where you thought there was another world, people suffering, and that we were going to do things.

At the time of the punk movement, before making films, did you have any idea of this reality? This neighbourhood? Was it something you talked about?

No, we didn’t really talk about it, we were autistic. But it was the same everywhere, I imagine, even if in Europe it was very different from what we experienced. Here the divide was and still is very pronounced: there are rich people and poor people, you can see that. There are rich people, a sort of middle class, and then there’s the proletariat, people who have nothing in common with the others. A huge immigrant population, Black Africans. Something that Spain doesn’t have, for example, but we’ve always had here: the reality of miscegenation. Which is not to say that they are integrated and that we all live in a democracy, far from it. But the Portuguese don’t even need to be racist towards Africans, because they are racist amongst themselves, and to such a degree of refinement that we can even enjoy misfortune. Portugal has always benefited from the power of misfortune. But we didn’t think about it, we just repeated slogans, the revolution... Some were communists, very leftist, anarchists – we were all very left-wing. We hated people on the right, every word was a bit dangerous. Sometimes a guy would come into our circle and say things... It could be something about your hair, or your jacket, it was a time when we dressed up a bit... And that guy very quickly became a bourgeois fascist, a Nazi, he was expelled. It was at that level, it didn’t leave the bedroom, the bistro, the neighbourhood. You didn’t go anywhere else. Some of us, the older ones, had a little experience of popular culture. We were twenty or twenty-five, but the people who were doing it were thirty, they were already teachers, they’d just left university.

The return to the land, the occupations?

Yes, they’d leave university or leave and say: “It's no use, I’m going north, to the Trás-os-Montes, I’m going to be a teacher and educate them.” We knew these people. But I didn’t do it, we were very confined. Then I got the shock of Fontainhas. I had this “other half” in front of me that we didn’t see, that we didn’t talk about, and I’d stumbled into it by chance. And I seriously thought there was something to be done. Not what they did during the militant years, not what I saw in films either, because documentaries just fell out of my eyes. Even the most classic, even if I recognise the qualities or the rather beautiful things, of good will. To put it bluntly, like João Bénard da Costa: “I don’t like documentaries.” Even when I was in the neighbourhood, when I thought I could make a film there, I didn’t tell myself that I was going to denounce them or show how they live. Above all, I must admit, it was a shock to the eye and therefore to my senses: I saw it in a different way, it took me back to the beginning, to my bedroom. I said to myself: “I’m the only one here, the only filmmaker, no one else is going to make films in this neighbourhood.” That’s how it all started.

Mutual Films

In a film like In Vanda’s Room, where images are not spent like water (water is a scarcity for much of the world!), yet the images refuse to be thirsty or famished, it is impossible to mistakenly select an obligatory still-frame in a job like mine . But, the more one studies Vanda the more evident it becomes that to remove a single image from its before and after is to gravely threaten that image. In setting out to make something with still-frames from Vanda I had a sense of violating the trust of the film. Automatically one violates the film’s sound, an entire pole of its dialectic, its sense of population, trauma and memory (and memory, Costa told us in Los Angeles, is the strongest thing the people of Fountainhas have). So, in this sort of analysis and reverie one compensates for the loss of unity and sound with texts and juxtapositions. We all agreed not to walk on eggshells but to make intervening cleavages. However, faced with a film of community and the violence done to that community, it would be useless to chase totem pole sets of images or to get lost in seized numina; a numen which, to be sure, exists in the film, but a specifically realist divinity in people and objects that, like reality, is always “on the move”, circulating with a plastic bag, evicted and hoarse with illness. In the juxtapositions of this collage it would also be useless to go the route of simple visual resemblances or blasts of montage effects. In cinephile games one can easily lose sight of human rights and violations, not to mention the rights of the film itself. Early on, the film Vanda told me not to play cinephile games, not to throw around too many images from too many places, not to be too rash. She told me, like Huillet and Straub, like Malraux, like Marx, “More awareness,” and above all “Stick to the neighborhood.” To hang around the neighborhood of Fountainhas and a certain neighborhood of cinema. I tried to proceed then with the great spirit of comaraderie that the film exudes, to show two forms of Vanda’s and Costa’s intimacy and their interruption: solitude and togetherness.

A film is like the hanging chunk of taffy in Les Vacances de M. Hulot, it has its own push and pull, and the taffy’s working into the right consistency is a risk to itself that physically interrupts Hulot as he passes by it. Working with frozen images for this project, against fetishization, one must also be aware that a scene like this one from Les Vacances could never be conveyed via frozen images, the same way a certain coupling of shots in Vanda could never be conveyed in the film’s absence: in one shot a man is helping to clean out a home (his own?) and in the next he’s the operator of a bulldozer demolishing a house (his own?). Therefore in the stills and juxtapositions that were finally selected, all trust, as in Tati, is in the detail and the place.

The Place and History of every film, every ghetto, every war, and every child.

Andy Rector, 14 December 2007

[End of the first chapter of the book.]

This text and collages appeared originally in Dans la chambre de vanda. Conversation avec Pedro Costa (Capricci: Nantes, 2008).

With the courtesy of Pedro Costa, Cyil Neyrat and Andy Rector

Image (1) from No quarto da Vanda [In Vanda’s Room] (Pedro Costa, 2000)

Image (2): Pedro Costa and a bruxa [the sorceress]

Image (3) from No quarto da Vanda [In Vanda’s Room] (Pedro Costa, 2000)

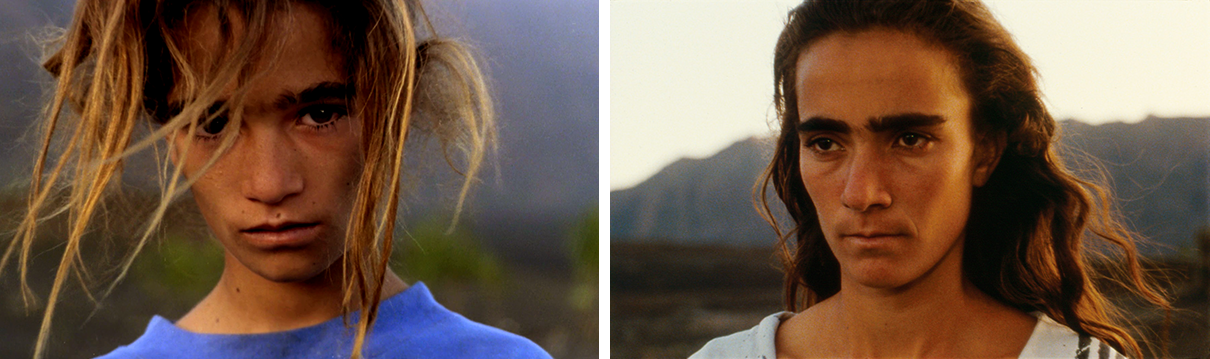

Images (4) and (5) from Casa de Lava (Pedro Costa, 1994)

Image (6) from Trás-os-Montes (Margarida Cordeiro & António Reis, 1976)

Image (7) from O Sangue (Pedro Costa, 1989)

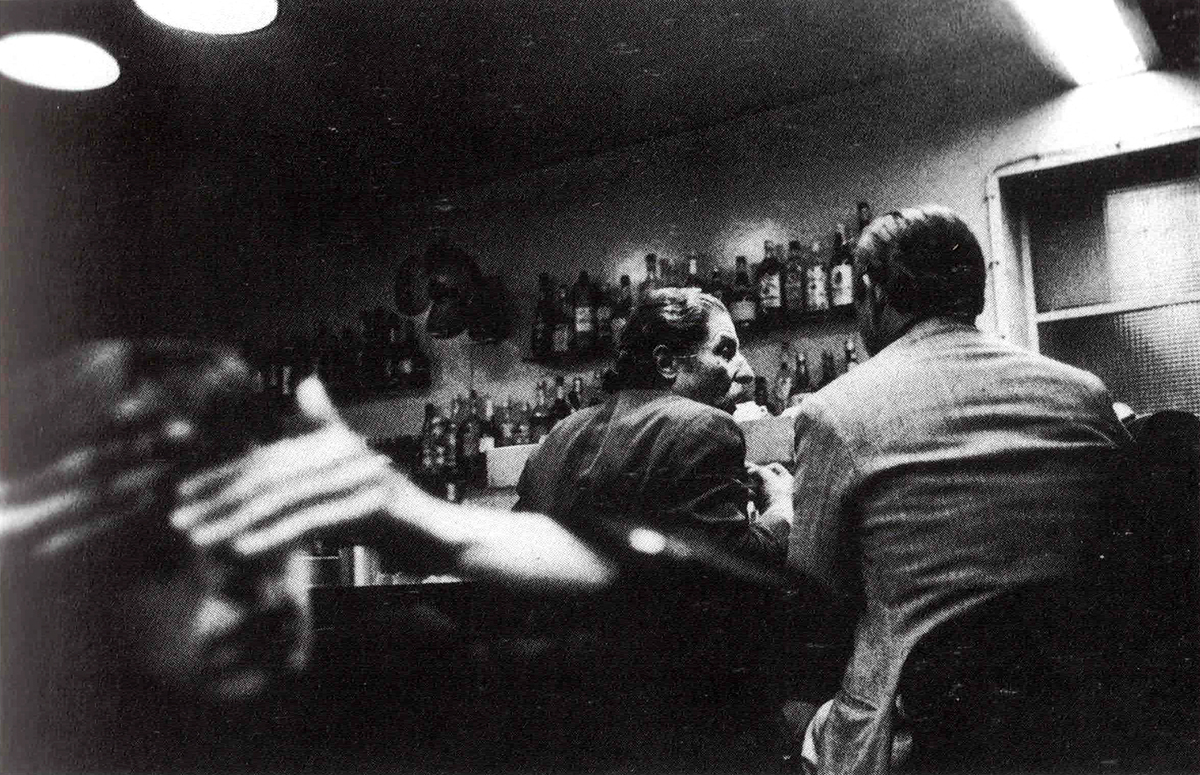

Image (8): Lisbon, 1979, the Tic-Tac. Photo by Paolo Nozolino, one of us

Images (9) and (10): Collages by Pedro Costa [Scans]

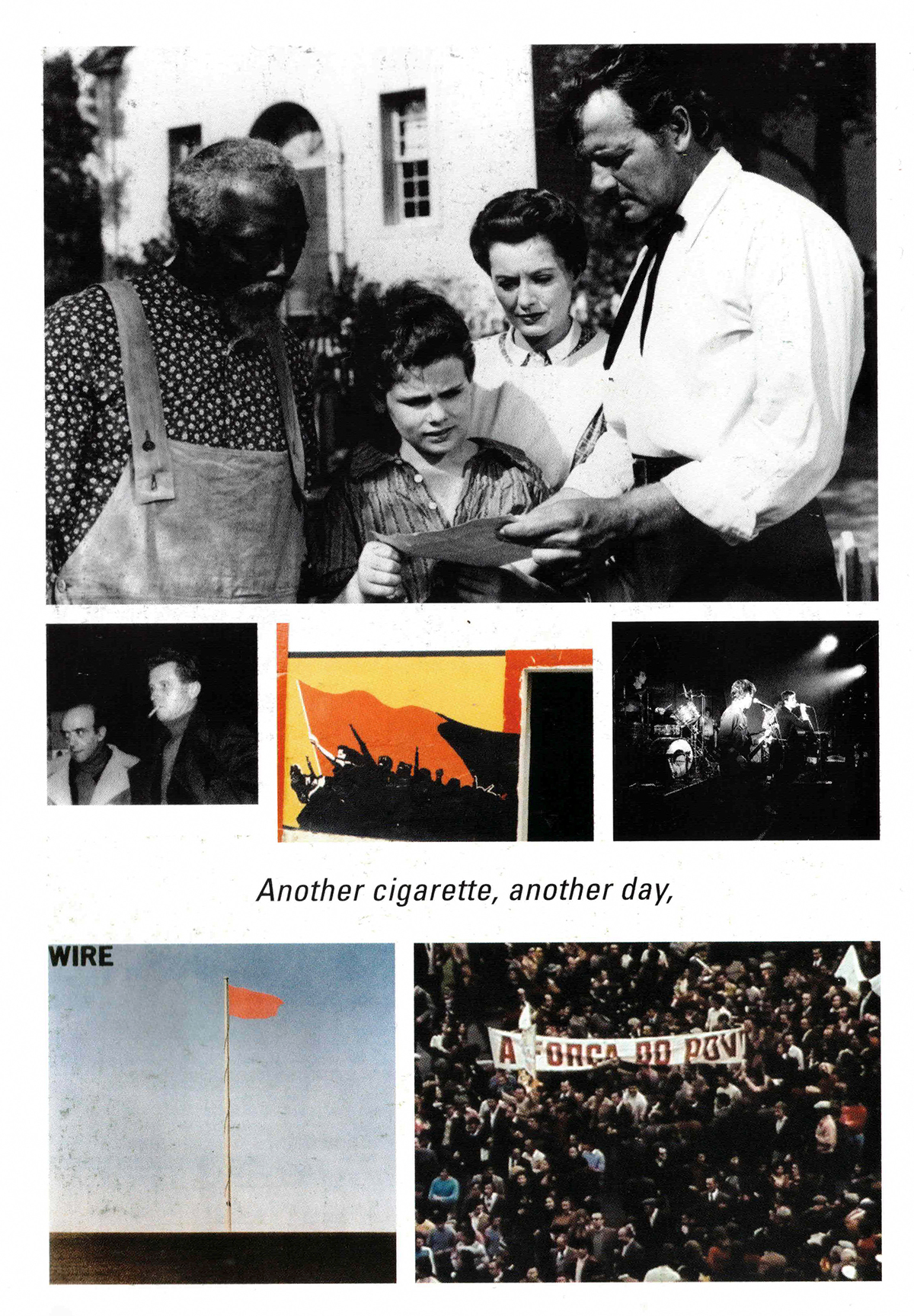

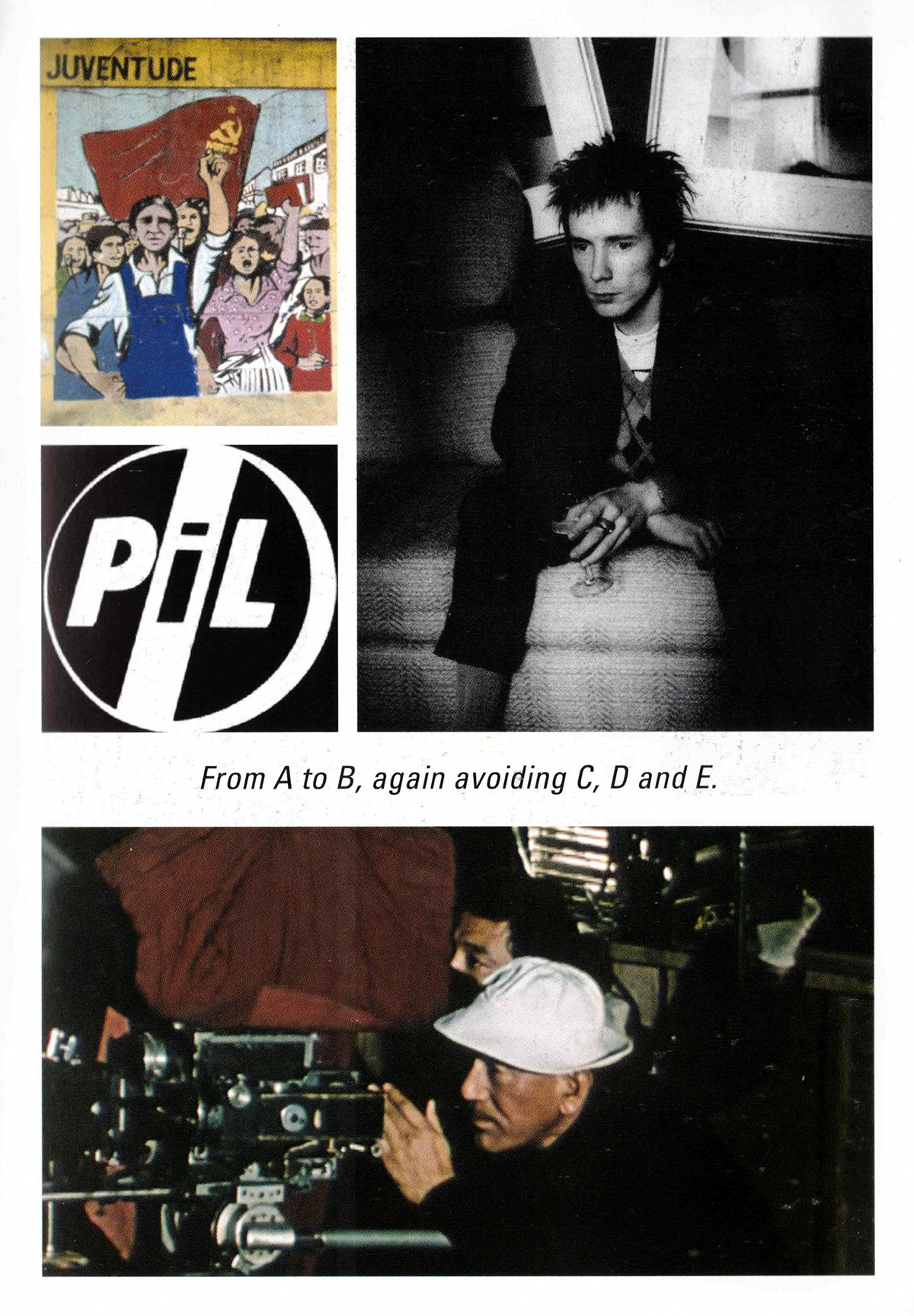

Images (11), (12), (13), (14), (15) and (16): Collages by Andy Rector [Scans]