On the Difference Between an Image

The Cinema of Víctor Erice

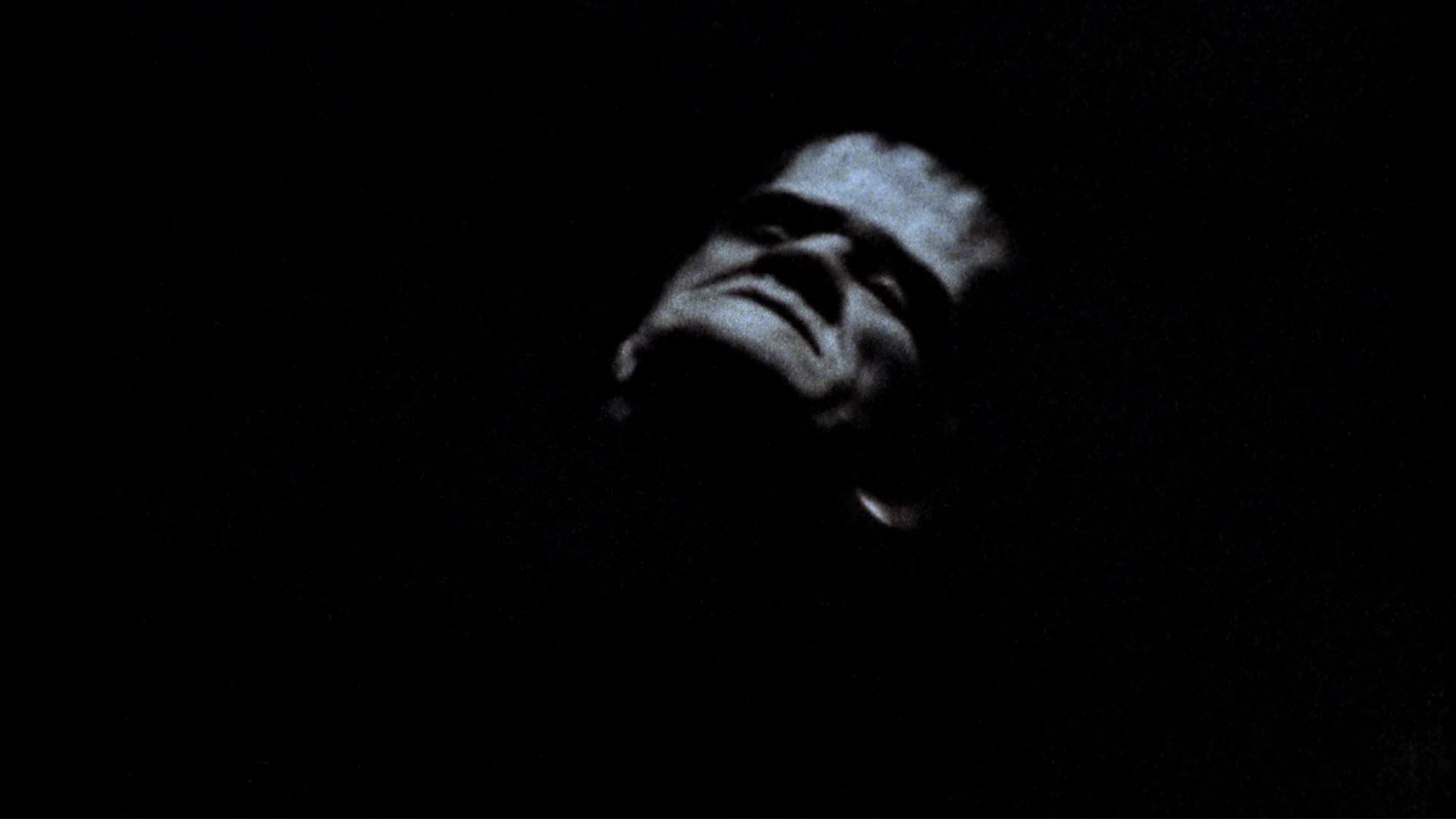

By night the little girl wanders through the depths of the nocturnal forest and squats at the edge of the river. On the surface of the water the shadows of the trees are already dancing, white outlines trembling beneath the pallor of the moon. The little girl contemplates the reflection of her face, twisted and deformed by the watery undulations, an unsteady image that does not settle, a blurry projection. The pale reflection in the black water makes sport of its new elasticity like a Chinese shadow or a distorting mirror. Suddenly it dilates so much that it becomes a blotch, allowing itself to be transfixed by a metamorphosis it is no longer the face of the little girl, Ana, which is formed on the back of the river, but Frankenstein’s, the hard features of the Spirit. Comparable, in beauty, to the marvellous vision of Sunrise or Night of the Hunter, the scene continues. Already to the back of Ana twigs are cracking neath heavy, clumsy footsteps. Frankenstein is there. He comes and kneels beside Ana, who opens wide her eyes before this apparition and almost opens her arms as well: she makes a vague gesture of the hand when those of the creature, the huge hands of the Spirit, slowly approach her shoulders. Then she closes her eyes, enraptured, submissive. The Spirit, that night, has possessed Ana. By what sorcery is Frankenstein’s face substituted for Ana’s? What is this crumpling of the image that opens onto a radical inversion, from a living girl’s face to the terrifying features of an imaginary monster? It’s a dissolve, one image and one alone, but which spreads out and binds together two worlds, that of living people and that of chimeras, pure identity and absolute change – one image and one alone, inhabited twice over, in which difference is registered but once, in the same instant. A reversal of the world that would drive a little girl still dazzled by shadows crazy. The inner difference of this image, drawn from the central scene in The Spirit of the Beehive (19730, is the object of quest par excellence of the cinema of Víctor Erice.

It has to be said that Ana has already seen Frankenstein, but only at the cinema, in the James Whale film. And that it’s the privilege of children to be born off this way by the kingdom of the spirits who inhabit the screen to the point of seeing them made flesh and touching your hand at night at the edge of the river.

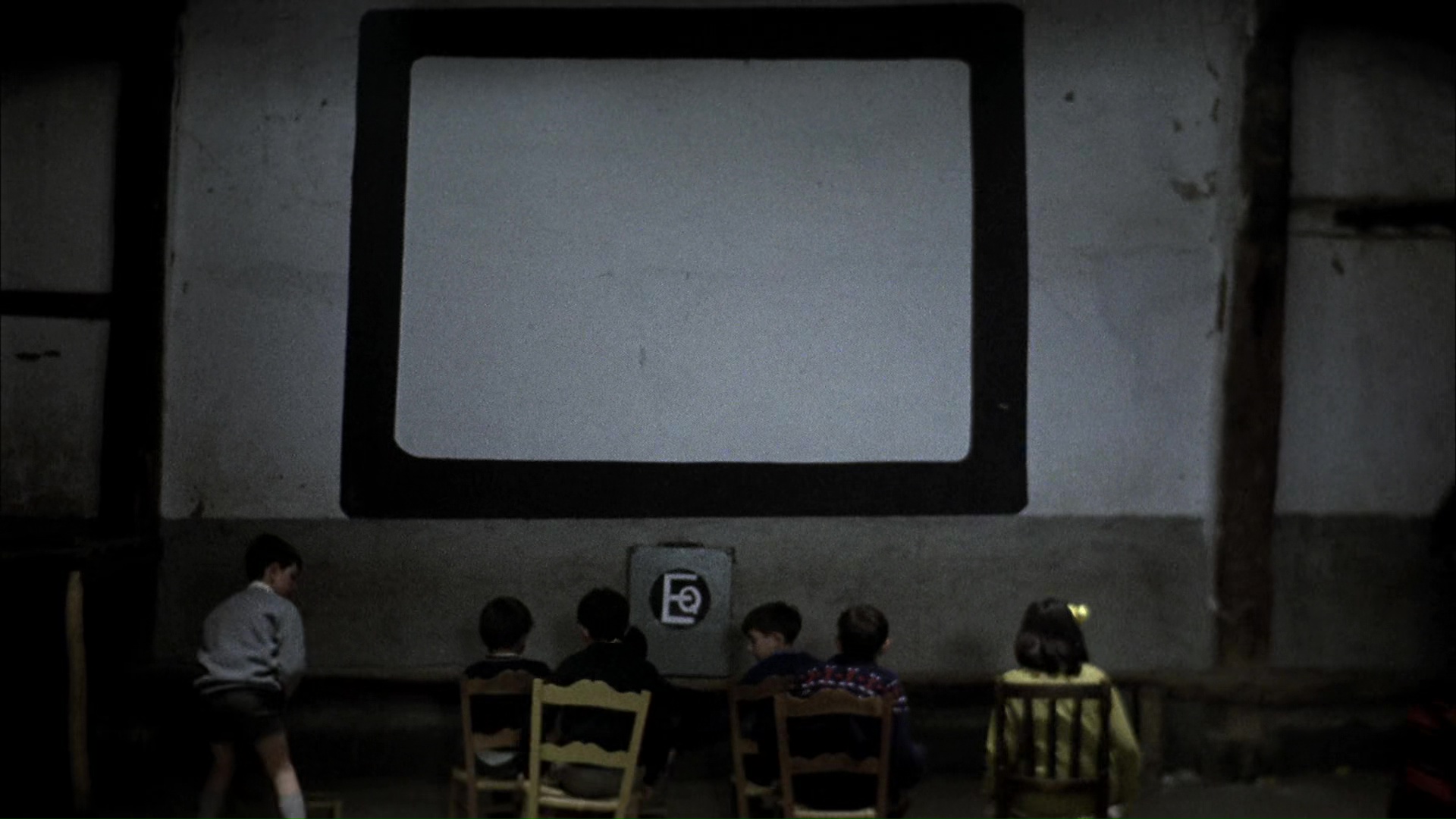

There are lots of banalities to utter on the relationship between childhood and cinema, all of them subsumed under the nice, mute label of “magic”. Well, more than enchanting them, the cinema possesses children, inflames them. Growing up means learning to content yourself with ashes, since the initial amazement is produced but once, and once alone, and only persists in the form of traces. This first time is wonderment and madness, and the word that would bring these forces together has yet to be invented, apoplexy perhaps, in any case something ephemeral and immense that Víctor Erice has managed to capture, miraculously, in Ana’s eyes.

Films that explicitly take the cinema as their subject also open the door to all kinds of vain, theoretical considerations, depending more on written reflection than on the cinema in action. It is on that perilous terrain – of films entirely traversed by a questioning of the nature and functioning of cinema – that the oeuvre of Víctor Erice is constructed, a director whose films are packed with direct evocations of the cinema-machine, evocations that extend from metaphorical translation to an unswerving concrete materialisation of the cinema-moment: a line of light striking the eye of a little girl (another one) through a keyhole from where she observes her father busy with other kinds of sorcery (The South, 1983): the shadow of a camera stretching along a wall, at the bottom of which fruit lies rotting (The Quince Tree Sun, 1992); or simply the faces of children straining upwards towards the screen, faces entirely given over to the entertainment of a film show (The Spirit of the Beehive).

Rather than being contented with a theoretical gloss on the art of the films, the challenge would be to give an image of this which would be primarily and at once a cinema image and an image of the cinema – one image and one alone, once more, the liveliest and most singular of images.

This is the privilege of two or three filmmakers, scarcely more. Perhaps Jean-Luc Godard, Abbas Kiarostami and Víctor Erice are precisely these. And the risk they run, in coming up against matter itself that way, is enormous, a risk of fatal redundancy. For Erice, it’s a temptation the prodigious actors and actresses at work in his films respond to. Each in its own way, The Spirit of the Beehive, The South and The Quince Tree Sun strive towards the “white of origins”,1 which is also the white of the screen at the moment the images, the phantoms, are ready to beleaguer it. In order to reencounter the intensity of first contact, before the loss that inexorably follows it. In the same way that a painter hastens to capture the light which threatens to fade away, a fruit which prepares to turn rotten. Cinema, for Erice, ages at the very moment of its birth, it never stops putting those first sensations at a distance. And there is no remedy for this loss, certainly not the one that would consist in reproducing something, as one places a sheet of tracing paper to reproduce a drawing. From his cinema Erice has banished forever the re-creation, pastiche, the incestuous and vain reference. Instead, he explores dream images, the imaginary, the empire of spectres and sometimes the captivating incarnation of Spirits. In short, projection. In a sense, all the developers, in the chemical acceptance of the word. Cinema's powerful powerlessness, of which the dissolve is the very expression, inasmuch as it expresses any difference hollowed out within a single shot, a single image, between the truth of Being and what it appears to be: at once an entire world and a kind of dust. Erice the filmmaker relentlessly tracks down what Erice the spectator saw one day when he bunked into a cinema where The Shanghai Gesture was being projected in a print cut to ribbons by the censors. Therein lies the risk of a congealing of the cinema in the contemplation of the faraway, in the waiting for an absolute Hollywood classicism perhaps momentarily got near to. But The Spirit of the Beehive, The South and The Quince Tree Sun succeeded in averting such a threat.

Perhaps the first two films are still in a state of dizziness, so much closer do they remain to the abyss that attracts little Ana: a definitive fall into cinema sorcery. And doubtless they draw from this danger the essential nature of their intense beauty. The Spirit of the Beehive, a night film, isa treatise on invoking phantoms. After seeing Frankenstein at the cinema Ana asks her sister Isabel, scarcely older than she is, why Frankenstein killed the little girl and what has become of him. The cinema is the empire of the false, replies Isabel, Frankenstein is a Spirit and if you want to see him pronounce the magic formula: “All you have to do is close your eyes and say ‘It’s me, Ana, it’s me, Ana.’” The South, a winter film, tells of the confrontation between a grown-up little girl, Estrella, and a mythic land, that South of which she possesses naught but stories, scattered signs. The South, from where her slightly sorcerer father comes, her adored father who slowly sinks into a depression when caught up by the image of a woman he loved in the past, present today in the darkness of the movie house, an actress, a vanished mirage. Like Ana, Estrella’s father is engulfed on entering the round of chimeras, to the point of madness.

This is where Erice’s cinema is at, in fact, when he meets the painter Antonio López in 1990 and begins filming him at work a few months later. Nevertheless, The Quince Tree Sun, a daylight, autumnal film, is born less of a documentary ambition than of an image from a dream told by the painter to the filmmaker, and which the latter has re-staged at the end of the film. Erice might have adopted as his own Abbas Kiarostami's beautiful phrase apropos of his film Five (2004), which he claims to having made in order to “wash the gaze clean.” After the childish reveries of The Spirit of the Beehive and The South, The Quince Tree Sun marks the moment of the amicable confrontation of the cinema with its eternal rival, painting, which Erice takes to be the outright winner. In the little garden of a suburban house, while some workers busy themselves on a building site, Antonio López attempts to paint a quince tree. The film chronicles this labour from day to day, yet without claiming a neutrality it cannot in any case lay claim to. It is perhaps the artificial lights used for filming that have caused the fruit to go rotten before the painter was able to finish his picture. The more the camera approaches, the more the image is adversely effected, because the camera “rots the natural,” says Erice. The quinces are akin to memories, with the lustre of the first day of the cinema, and if The Quince Tree is a treatise on joyfulness it also recounts the weight of things (the white paint marks on the yellow skin of the quinces, which serve to mark the progressive sagging of the tree bending beneath the weight of its fruit) and the death to come.

It needs saying where these films are born, the hollow of the day or the back of the night. The South opens, then, on the birth of the daylight, which spreads little by little through Estrella’s bedroom, in which her father has left the indication that he has left forever. Films that are born in the smoke of a train present in each of them, come from elsewhere and are bound for a here-after. The train which ejects a wounded soldier in The Spirit of the Beehive whom Ana goes to visit, taking him for a Spirit. The train that awaits the father in The South and which he will not take, a train whose imminent departure for the country of his dreams is punctuated by the pulsation of the light during the dissolves, through the window of a hotel room in which the man who sleeps resembles Antonio López striking the pose for his wife, a painter herself, a drowsy López given over to a slumber that is strangely death-like. Lastly, the train of The Quince Tree Sun, which departs from or arrives at Chamartín, and marks the coming then the passing of the day, announces the time of repose for the painter, back home after a day’s work.

We have to go back to the original image, to rediscover the lost link, even though this first image is anything but pure, being already wounded to the quick by a difference, an incompressible discrepancy. The whole problem of Víctor Erice’s cinema lies here: filming involves following on from this image, and that is impossible. The second image is an absence. Víctor Erice’s trajectory reveals the capacity of this difficulty – not to say impossibility – to carryon via two moments of disillusion. One concerns The South, the adaptation of a short novel by Adelaida García Morales,2 a tale in three parts of which Erice will only shoot the first two due to a disagreement with his producer, Elías Querejeta. The other is an adaptation of the novel by Juan Marsé, El embrujo de Shanghai, on which he worked for a long time before arriving at a complete scenario, La promesa de Shanghai,3 a project finally allotted to Fernando Trueba. These two accidents with a painful outcome add, notwithstanding him, to the filmmaker’s legend. Erice has shot three major feature films in thirty years. This is little, but the films are immense. And this quantitatively minuscule output gives rise to misunderstanding. From this lack of prolixity it would in fact be all too easy to extrapolate the figure of a cineaste filming solely in an exceptional mood of inspiration – very rare moments that only arrive a few times in the life of an artist, who must wait and wait. Now, Víctor Erice insists on the contrary on hard work, daily activity: “I need to work,” he says, “you've got to work.”4 Working does not exclude patience, on the contrary, or interruption. But for thirty years Erice has never ceased dreaming up ideas for films, being involved, via writing (notably on Nicholas Ray5 ), in thinking about cinema, of lighting wicks which have not burned as long as was hoped. This presence, be it stippled, signifies more than the mythic aura, inevitably cumbersome, museum-like, freely granted him. Apropos of aborted projects and of the third part of The South, there are no grounds, either, for imposing an aesthetic of the incomplete, of “hindrance,” where there is none. To be sure, we may think that The South gains from the fact that it remains open, through the force of circumstances. Doubtless Erice observes Antonio López with envy as he finally puts away, without sadness, his quince tree painting, unfinished because autumn has descended all of a sudden and its fragile and fleeting, beautiful light has got the better of the canvas. But, without prejudging the quality of a film which does not exist, it would be unjust to think that La promesa de Shanghai did not get made because it ought not to be made, that this was in short its fate. Films, like phantoms, should all exist; something’s missing if they don’t come about.

In three films Víctor Erice has constructed a fragile body of work, with a painful coherence. It begins and ends straightaway, from the very first images, once the bridge is crossed and we let the phantoms come to meet us. It is entirely, and in a single movement, total openness. To Being, to the Spirits. A haunted cinema in which spectres take little girls by the hand. The references to Don Quixote dotted throughout the oeuvre point to a political preoccupation (the portrait, ever on the stocks, of post-civil war Spain, that of the filmmaker’s childhood), and bespeak what modality of the fantastic Erice believes in, the fantastic as a ballet of chimeras or a dance of Chinese shadows or a dissolve. A dissolve without a cut between two worlds. Only the trees know the secret passage linking them. Those leaning over Ana at the moment Frankenstein appears to her. Or that avenue of plane trees in The South, a perspective view which accompanies the passage of Estrella from childhood to adolescence, from the North as experienced to the South as imagined, since the film ends on these words “I was finally going to get to know the south.” A fruit tree that claims all of Antonio López’s attention, and on which it is henceforth cameras and projectors that are trained.

It is said that on the shooting stage of The Spirit of the Beehive Erice had asked everybody to talk in hushed tones, to murmur, whisper, so as to protect the reverie of Ana Torrent, a little actress with incredible presence. A cruel gentleness, since at the same moment the child confronts the greatest peril and is infinitely alone at the edge of the abyss, alone in the cinema screen, lost in the magic forest where the Spirit lives, alone in the middle of this dance which saves you or kills you or drives you mad, the representation of wonders.

- 1The phrase is Víctor Erice’s the post-scriptum of the beautiful posthumous collection of texts by Alain Philippon, Le blanc des origins, écrits de cinema (Yellow Now: Paris, 2002).

- 2El sur, Anagrama, Barcelona. 1985.

- 3La promesa de Shanghai, Plaza & Janés, Barcelona, 2001.

- 4Cahiers du Cinéma, no. 457, Paris, June 1992.

- 5Nicholas Ray y su tiempo, Filmoteca Española, Madrid, 1986.

Originally published in Erice – Kiarostami. Correspondences (Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, 2006).

Image (1), (2) and (3) from El espíritu de la colmena [The Spirit of the Beehive] (Víctor Erice, 1973)

Image (4) from El sol del membrillo [Dream of Light] (Víctor Erice, 1992)

Image (5) and (6) from El sur [The South] (Víctor Erice, 1983)