Tillo Huygelen

Tillo Huygelen (1993) is a Belgian filmmaker based in Ghent. He holds a master’s degree in international politics from Ghent University and a diploma in audiovisual arts from the KASK School of Arts in Ghent. Since 2021, Huygelen has been working as an editor and artistic collaborator for Sabzian.

Tillo HuygelenWeek 26/2025

We start the week with a screening of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) at NW Aalst as part of a focus programme on Belgian filmmaker Johan Grimonprez. His film Double Take casts Hitchcock as a paranoid history professor, unwittingly caught in a Cold War-era meditation on doubles, surveillance, and media-fuelled anxiety. Vertigo, one of Hitchcock’s most iconic films, follows retired detective Scottie Ferguson as he struggles with acrophobia and his obsession with tailing a mysterious woman through 1950s San Francisco. What begins as a case of routine surveillance gradually spirals into a haunting study of identity, illusion, and male desire.

On Thursday, De Cinema presents The Hour of Liberation (1974) by Lebanese filmmaker Heiny Srour. The film documents the Dhofar Liberation Movement in Oman, offering a rare and urgent portrait of a Marxist, feminist revolution in the Arab world. Shot under extreme conditions, Srour’s work foregrounds the voices of female fighters and imagines a radically egalitarian future. In her own words: “Our enemy is any cinema that turns its back on historical emergencies, taking refuge in a mythical past through a contemplative approach that is nothing but a flight from the present.”

Finally, on Sunday, CINEMATEK screens the seldom-shown Sehnsucht (2006) by German filmmaker Valeska Grisebach. This understated second feature follows a locksmith torn between his quiet marriage and a fleeting affair. As in her other films, fiction serves primarily as a framework for closely observing people – their faces, gestures, and presence – rather than driving the plot. The screening is part of a carte blanche selection by Mexican director Carlos Reygadas, whose own films were featured earlier this month at CINEMATEK following his visit to Cinema RITCS. Grisebach discusses her film in this 2019 Sabzian interview, recorded during a visit to Belgium.

Week 21/2025

For their spring programme, CINEMATEK and Courtisane have invited American filmmaker Billy Woodberry, a key figure in the L.A. Rebellion movement. Woodberry’s small but highly significant body of work will be featured in a retrospective running until 31 May. As a first pick in our selection, we highlight Bless Their Little Hearts (1984), Woodberry’s first feature, which emerged from the L.A. Rebellion scene alongside contemporaries such as Haile Gerima and Charles Burnett. The film is considered one of the finest produced by the collective. Burnett served as the film’s cameraman and cinematographer, while Woodberry directed and edited. Its simple, discreet, and almost shy tone stands in contrast to the often furious energy of protest cinema.

As part of the retrospective, Woodberry has also compiled a carte blanche programme. Alongside films like Notre musique (Jean-Luc Godard, 2004), O movimento das coisas (Manuela Serra, 1985), and Ceddo (Ousmane Sembène, 1977), he has made a curious selection of documentaries by Henri Storck and Joris Ivens. One can only speculate on Woodberry’s reasons for choosing them, but the social consciousness evident in Misère au Borinage (1934), and the formal experimentation in The Bridge (1928) and Images d’Ostende (1929), speak volumes in regards to the sensitivities of his own work.

The final film in our selection diverges from the others but certainly earns its place through its rebellious spirit: John Cassavetes’ Gloria (1980). This atypical film in Cassavetes’ oeuvre stars his wife, Gena Rowlands, as Gloria Swenson – a tough, chain-smoking ex-gangster’s moll. She becomes the reluctant guardian of a six-year-old boy who’s targeted by the mob after his family is murdered. Armed with a revolver, Gloria embarks on a perilous journey through New York City to protect the child. Rowlands' performance is widely regarded as one of her most iconic, earning her an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress. Roger Ebert described the film as “tough, sweet and goofy,” highlighting Rowlands’ ability to infuse depth into a genre piece.

Week 12/2025

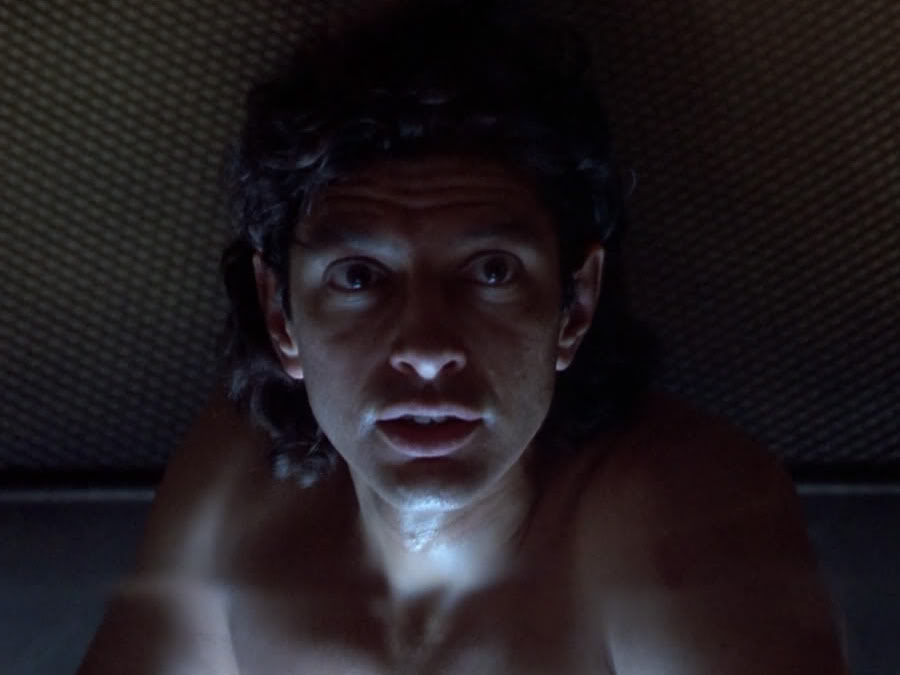

American actor Gene Hackman passed away last month. In what was certainly one of his most iconic roles, Hackman played the paranoid surveillance expert, Harry Caul, in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974). Coppola’s film is, first and foremost, a masterful lesson in film sound. For that reason, Thai film director Apichatpong Weerasethakul considers The Conversation as one of the five artworks that inspired his own film Memoria (2021). In both films, sound opens up a mysterious third space. As Apichatpong explains: “Coppola’s The Conversation was an enigma during my teen years. I viewed the VHS copy of the film and couldn’t understand the key sentence that Frederic Forrest whispered to Cindy Williams. Gene Hackman spends the entire film trying to crack the phrase. I spent more than 10 years, with countless re-watchings, until the film blossomed in me like a beautiful infection. Despite the VHS’s humble sound quality, this film triggered my infatuation with sound design in cinema.”

David Lynch, who was the subject of many homages and retrospectives after his passing, was equally adept at the use of sound in his films, which straddle the line between reality, the bizarre and the dreamlike – most notably in Mulholland Drive, arguably his most confusing film, where sound plays a crucial role in shaping the film’s amnesiac structure. Perhaps best exemplified by the “Club Silencio” scene where Betty and Rita find themselves in front of a spectacle of filmic sound devices: No hay banda!

Our final film predates the advent of synchronized film sound but still deserves a special mention. During the Japan-Square Festival, Studioskoop in Ghent is screening a 35mm copy of Fûun jôshi [The Castle Under the Wind and Clouds] from the CINEMATEK archive. The Castle Under the Wind and Clouds is a great example of the Japanese jidai-geki [historical drama] genre. It follows a samurai who returns to his homeland after three years, only to discover, to his dismay, that his fiancée has become a concubine of the prince. As part of the festival, you can also enjoy a delicious Japanese curry beforehand!

Week 8/2025

Queer cinema has long been a space for radical storytelling, challenging dominant narratives and opening up new ways of seeing. This week’s films are odes to queerness and defiance.

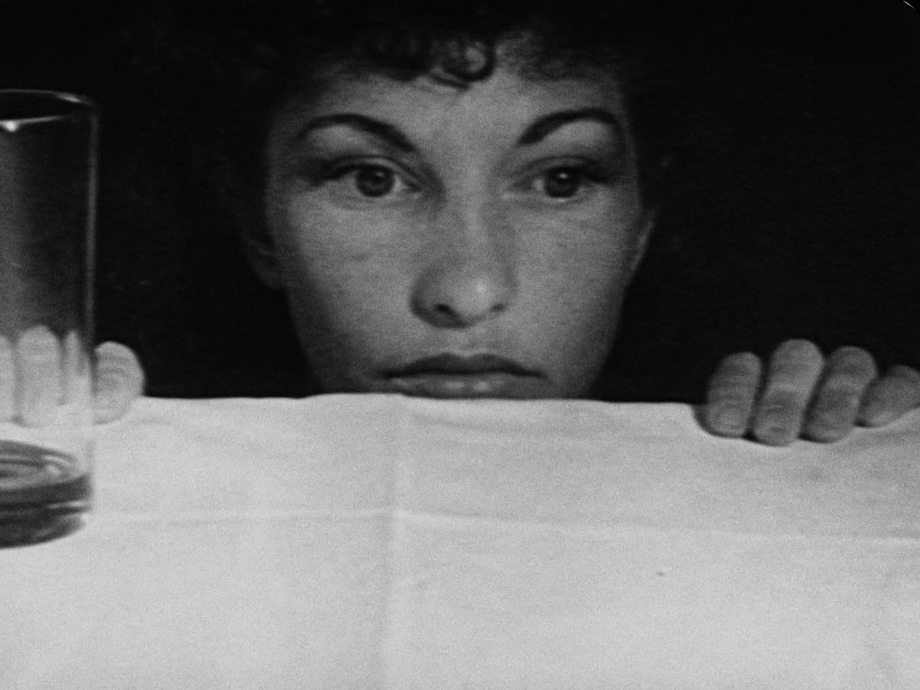

De Cinema opens our selection with De cierta manera [One Way or Another] (1974), the only feature film by Cuban filmmaker Sara Gómez. While not a queer film per se, its fluid blending of fiction and documentary, along with its critique of rigid social structures, establishes a queering perspective as the first feature to be made by a woman in Cuba. The film follows a romance between a teacher and a bus driver, exploring how class, machismo, and racism intersect in everyday life. A statement from the opening credits also nicely set the tone for the films in this overview: “Feature film about real people and some fictitious ones.” Preceding the screening is a lecture by Wouter Hessels on Latin American cinema of the 60s and 70s, contextualising Gómez’s work within broader cinematic and political movements.

Also at De Cinema, but later in the week, is Funeral Parade of Roses (1969), Toshio Matsumoto’s avant-garde depiction of Tokyo’s queer underground. Following Eddie, a transgender hostess caught in a web of desire and betrayal, the film is an explosion of experimental techniques, blending pop art aesthetics with political unrest. Matsumoto described its structure as letting a mirror fall to pieces and picking up the shards to piece it together again. Rumoured to have influenced Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, it remains a landmark of the Japanese New Wave.

At KASKcinema, A Rainha Diaba [The Devil Queen] (1974) shifts the focus to the underbelly of 1970s Rio de Janeiro. Inspired by a real-life figure, this film follows the flamboyant and ruthless drug lord Rainha Diaba. Director Antonio Carlos da Fontoura crafts a violent, camp spectacle that prefigures the aesthetic of Pedro Almodóvar’s early films. As da Fontoura put it: “What fascinated me as a director was the possibility of inventing a different reality, far from all polite limits, in camera movements, strident sound, art collages, set decoration, costumes, subversive makeup, penetrating music, burlesque acting, in the red of blood, in the gold of sequins.”

Week 4/2025

The news of Donald Trump’s second inauguration will be the first major story to digest this week. His resurgence in American politics has led some to proclaim that the next ten years will be “the decade of the bully.” Does cinema still have the courage to challenge or subvert the white, male, misogynistic impetus running through politics today? We can only hold onto the belief that it does. Hopefully, this week’s collection of films will provide a much-needed antidote.

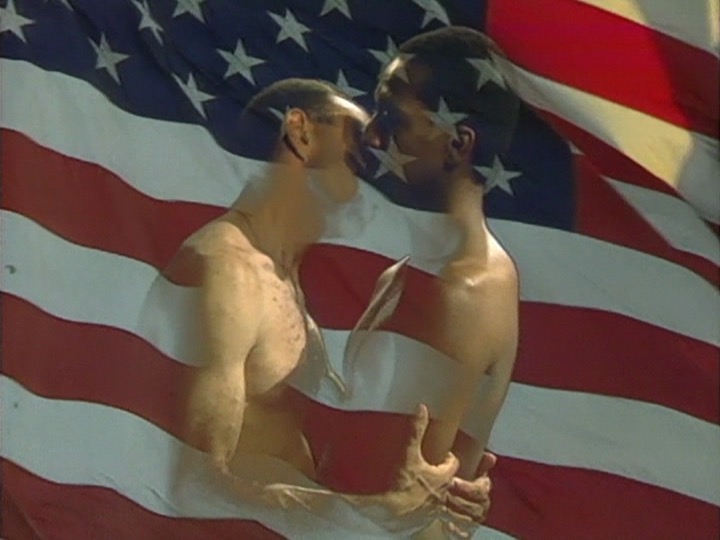

Beursschouwburg leads the way with two film programmes during its festive inauguration weekend. The first programme celebrates Black gay filmmaker, educator, poet, and activist Marlon Riggs. Tongues Untied (1989) is an essayistic video collage blending various forms of expression: spoken poetry, interviews, rap, performances by poet Essex Hemphill, and sequences of dancing and voguing that boldly reflect the influence of music videos. As a documentary, it examines the intersection of homophobia and racism faced by Black gay men; as a work of art, it celebrates Black gay identity and defies its silencing. The film is accompanied by two of Riggs’ later short films, Anthem (1991) and Affirmations (1990). The second programme features Alice Diop’s Vers la tendresse, a tender portrait of four young men and their perspectives on masculinity, screened alongside mercedes comme papillon, a student short by Marthe Perret.

On the same evening, CINEMATEK presents a screening of Ernst Lubitsch’s Design for Living (1933). This elegantly crafted film, a collaboration between Lubitsch and soon-to-be Hollywood legend Ben Hecht, explores the complexities of a ménage à trois with Fredric March, Gary Cooper, and Miriam Hopkins in a way that stands far apart from its era. Far from moralising, it offers a nuanced and freewheeling take on human desire.

Week 49/2024

The first week of December starts with a difficult decision. Monday offers two poignant screenings. In collaboration with Courtisane and Eye on Palestine, KASKcinema begins the week with a screening of A Fidai Film (2024) by Kamal Aljafari. The film presents rare moving images of Palestinian life before and after the Nakba, taken as spoils of war during the Israeli invasion of Beirut in 1982. Aljafari poetically interweaves history with art, grief with longing, and resistance with sabotage. Every image and montage bear the traces of this rich, layered mix of personal and collective memories. The screening is preceded by a lecture-performance by Mohanad Yaqubi, a Palestinian filmmaker and co-founder of Idioms Film, exploring archiving as a counter to oblivion and translating kinships into inventories, transcripts, and captions.

Also on Monday, Art Cinema OFFoff is showing Extreme Private Eros: Love Song (1974) by Kazuo Hara, a film of incredible intimacy. When his ex-wife called Kazuo Hara to film the birth of their child, the filmmaker travelled to Okinawa and filmed her for two years with a 16mm handheld camera. “The only way to keep the relationship was to make a film,” Hara reflects in a voiceover at the film’s opening. Still in love, obsessive, and jealous, he portrayed his ex, Miyuki Takeda, while she was in a relationship first with a woman and then with an African-American G.I., with whom she would have a child. Over time, Miyuki asserts herself more and more vis-à-vis Hara, using the film as a stage and a record of her sexual rebellion. Extreme Private Eros will be presented by Clara Spilliaert in the context of her solo exhibition My Sister is Pregnant, currently showing at Kunsthal Gent until December 29.

Our third film of the week, Sambizanga by Sarah Maldoror, was selected by Alice Diop for Sabzian’s annual State of Cinema event in 2023. The film portrays Angola’s struggle for independence through the eyes of a woman whose husband is imprisoned and tortured to death by the Portuguese due to his involvement in the burgeoning independence movement. Like the two preceding films, Sambizanga presents a powerful critique of dominant perspectives – in this case, a white, masculine and colonialist viewpoint.

Week 45/2024

Over the past weeks, many of Johan van der Keuken’s early films have been shown as part of Sabzian’s Seeing, Looking, Filming retrospective, presented in collaboration with CINEMATEK. This week, our seventh programme will be screened, featuring two of Van der Keuken’s extraordinary films about blind children. In the second film, Blind Child II (1966), Van der Keuken returns to Herman Slobbe, one of the children from the institute portrayed in Blind Child (1964), who’s now an adolescent. It is in this film that Van der Keuken memorably bids farewell to the subject of his film, reflecting on the fact that everything in cinema, even Herman, is ultimately a form: “Goodbye, gentle form.”

Van der Keuken’s seemingly simple declaration resonates deeply with many filmmakers, especially those behind the camera, who are faced with the fundamental questions of documentary filmmaking. When confronted with today’s images of destruction and suffering, it’s no surprise that different venues and their audiences are drawn to films that bestow dignity upon the “forms” they depict – in stark contrast to the dehumanizing frames that are rampant today. In this light, the rarely screened Wild Flowers: Women of South Lebanon (1987) by Mai Masri and Jean Khalil Chamoun will be shown at Cinema RITCS. Masri and Chamoun focus on the women who played a crucial role in resisting the Israeli invasion of southern Lebanon. Preserving their stories on camera, Wild Flowers is a film about courage, resistance, and hope.

On Tuesday, KASKcinema and Film-Plateau are hosting filmmaker Fairuz Ghammam. She’ll present a short film programme titled ‘Dreams, Landscape & Borders’, which explores internal and natural spaces. This includes Step by Step (Ossama Mohammed, 1978), a documentary that begins with village children optimistically discussing their dream jobs, but quickly reveals that this innocent hopefulness will not last. Also included is Bamssi (Mourad Ben Amor, 2024), where urgent, Instagram-like images engage in dialogue with family abroad – Mourad and Fairuz, Tunisia and the world. The final film, The Trip (2019), is a road movie through the rugged, majestic landscape between the Texan cities of Marfa and Alpine, with poet Eileen Myles at the wheel offering guidance to its curious passengers.

PART OF Sabzian Events

Johan van der Keuken Retrospective

Week 40/2024

With a quote from Raymond Bellour, who said that “narrative cinema is a machine for creating the couple,” Australian critic Adrian Martin opens his extensive review of Wong Kar-wai’s Fallen Angels – one of the films in this week’s selection – saying that “cinema is obsessed with love, with romance, and most especially with the couple.” This week’s films are all New Wave films, from different times and places, that subvert the traditional and classic portrayals of romance on screen.

In La Paloma (1974), Daniel Schmid abandons the use of a traditional script altogether, with the story merely serving as a trigger for “pure imagination”. Not a shred of emotion remains, only a willed and constant mise-en-scène of melodramatic feelings. As Schmid himself remarked about his film: “La Paloma is about love, understood as an absolute fiction. It is not that love occasionally makes a mistake; rather, it is by its very nature a mistake. What one thinks is a bond with another person is revealed to be a new dance of the lonely self. Love thus becomes a medium of self-expression.”

Like La Paloma, Wong Kar-wai’s Fallen Angels is also an “elegy to loneliness.” Tony Rayns even argues that “loneliness is ultimately the film’s centrifugal force.” Originally conceived as part of Kar-wai’s Chungking Express, the film delves deep into the nocturnal world of Hong Kong, following a string of detached and lonely underground figures. To cite Adrian Martin again: “Everyone in Fallen Angels is either too close or too far apart. Lovers never meet, but strangers suddenly grasp each other in bars to rave, or wail and cry on a shoulder. They all search for a middle distance, a comfortable, shared ground, that they can never find.”

The same could be said for our next film, Jules et Jim (1962) by François Truffaut, though both films are clearly products of their time. In Jules et Jim, a ménage à trois unfolds between best friends Jules and Jim, and the free-spirited Catherine (Jeanne Moreau). Like Ingrid Caven in La Paloma, Jeanne Moreau’s character is a distinctive, iconic, and unsettling screen presence. “For Catherine [...], only her current desire mattered,” Chantal Akerman wrote. She continues: “If people suffered because of it, she couldn’t care less. It was everything, right away, and in any way possible.” Unfortunately, their love story is ultimately as doomed as the others.

Chante Akerman

The fifteenth episode of The Bandwagon, Sabzian’s irregular series of film-related mixes, by editorial member of Sabzian Tillo Huygelen and photographer and film historian Hilde D’haeyere. This episode is dedicated to singing and the natural voice in Chantal Akerman’s films.

Week 25/2024

Wang Bing’s penultimate documentary, Youth (Spring), is being shown at Cinema Galeries this week. Filmed over five years in Zhili, a city 150 km from Shanghai, it portrays young migrants from rural regions around the Yangtze Delta who flock to a textile manufacturing hub seeking sustenance. Bing condensed 2,600 hours of footage into a three-and-a-half-hour mosaic that captures their toil and transient relationships amid seasonal changes, bankruptcies, and family pressures. As Bing explained in an interview: “Film and traditional narratives often seem to pick an individual out of the multitude of lives around us, like one fish out of the sea, and turn this person into a hero meant to stand for the world. I didn’t want that spotlight effect. I prefer to see all these characters swimming together in the ocean of everyday life, and try to capture something in each of them to suggest the personal difficulties they’re facing and the essence of their individual story.”

Our second pick is a special screening of Chantal Akerman’s La folie Almayer (2011). Based on the novel by Joseph Conrad, the film tells the story of Western businessman Kaspar Almayer, whose dreams of a bright future for his beloved daughter Nina are crushed under the weight of his own eagerness and bias. Akerman described it as “a tragic history, like ancient tragedies that never grow old. A story as old as the world. A story as young as the world, of love and madness, of impossible dreams.” The screening will be followed by a master class in French with production manager Marianne Lambert, who will talk about her work on the film.

The final film, Wir haben lange geschwiegen by Frauenfilmgruppe München, is part of the We Have Long Been Silent programme that was featured at this year’s Courtisane Festival and now runs at CINEMATEK. Presented by programmer Kristofer Woods, this series revisits the history of New German Cinema from the perspective of its female directors, often overlooked by history. Sabzian previously published interviews with Ula Stöckl and Helga Reidemeister and will release an interview with Cristina Perincioli next week.

Week 17/2024

This week begins with a screening of Retratos Fantasmas [Pictures of Ghosts] (2023) at KASKcinema. Set in Recife, the Brazilian coastal capital of Pernambuco, the film is a journey through time, sound, architecture, and filmmaking. It delves into the historical and human territories traced by grand movie theatres that were at one point central to social life in the 20th century. These venues, once full of dreams and progress, reflect significant shifts in social practices and are explored as part of a city’s cinema-infused cartography.

On Friday, De Cinema in Antwerp invites the Royal Conservatory of Antwerp to present a program of experimental shorts by Germaine Dulac and Maya Deren. “When making a film, the story is usually put in the foreground while the image stays in the background, that is, theater is preferred over cinema. When the relationship will be inversed, cinema will begin to live according to its proper meaning. […] The future belongs to the film that cannot be told,” proclaimed Germaine Dulac in 1928 – a principle that resonates in Maya Deren’s work as well.

We conclude the week at the Afrika Film Festival in Leuven with a screening of this year’s Berlinale winner, Dahomey (2024), by Mati Diop. In Dahomey, the return of twenty-six royal artifacts from the Kingdom of Dahomey to the Republic of Benin – after being looted by French colonial forces in 1892 – sparks debate among University of Abomey-Calavi students. When asked what spurred her to make the film, Mati Diop reflects: “I never envisioned what restitution could look like. Imagining it inspired a film about the odyssey of a looted artifact, projecting its homecoming into the future. It's a vision that stretches from the past looting to a speculative return in 2075, a narrative of cultural reclamation I thought I might never witness.”

Week 9/2024

On Monday, Bozar, Avila, and Sabzian present a unique cinema concert. Pianist Seppe Gebruers will accompany Charles Dekeukeleire's avant-garde masterpiece, Histoire de détective (1929), live on two grand pianos. The dogma of harmonic consonance will be questioned, as Dekeukeleire rejects linear narrative forms and employs parallel montage, and the music will dialogue with the film’s playful absurdity and surprising rhythms.

Two days later, Art Cinema OFFoff and Ciné Rio present another ciné-concert in Ghent. In the performance Traversées, artist Jelle Martens will engage in a live dialogue with two of Brussels-based filmmaker Els van Riel’s films. Van Riel explores the basic elements of cinema in her work, often working with 16mm film and experimenting with the technique and simultaneous use of multiple projectors. Her films, videos, and installations explore the impact of detailed changes in moments, movements, matter, light, and perception. For Martens, sound is a crucial element in terms of rhythm, repetition, texture, and montage. In his work, he focuses on the dialogue between the mechanical and the human through repetition and reproduction. Els van Riel and Jelle Martens also chose to show the film Chimera (2019) by Haris Epaminonda, which explores “a quest for light and shadow, and for all the elements that make this quest visible.”

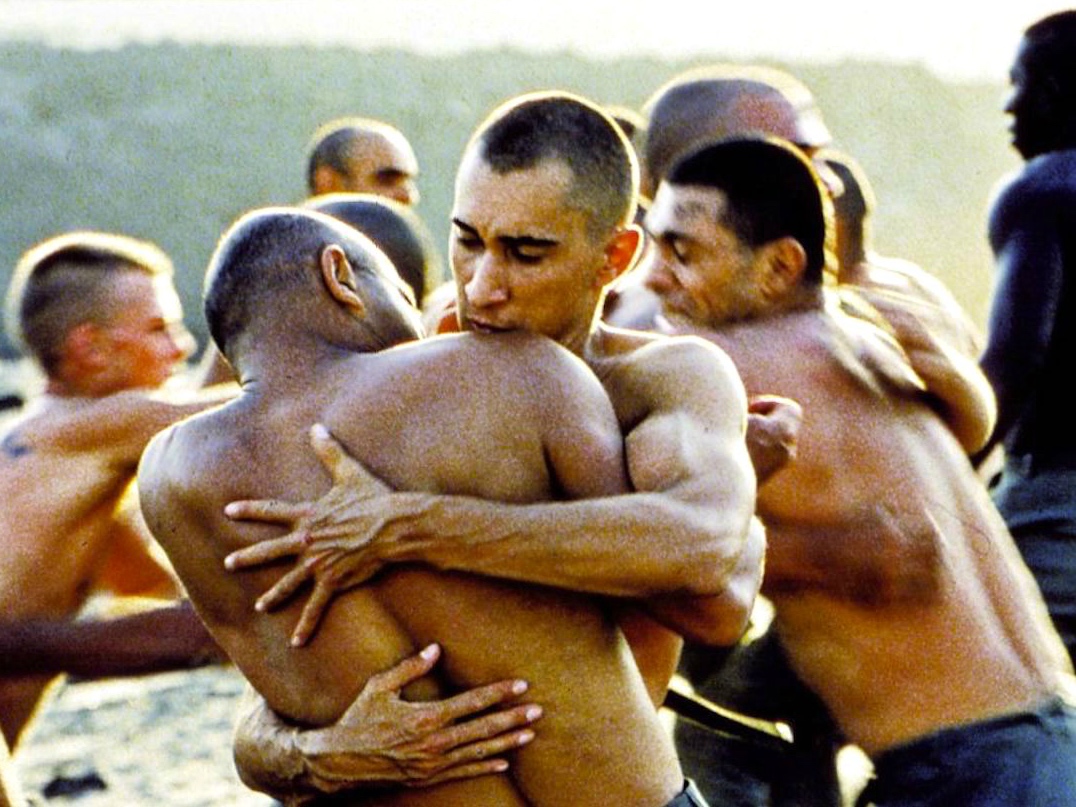

The final film of the week is Claire Denis’s Beau travail (1999). Set in a French legionnaire base in Djibouti, Beau travail shows the interaction of two different worlds: the ascetic lifeworld of the soldiers dominated by masculinity and the vibrant and sensual African society all around them. The film remains revered for its treatment of movement and the body, filming military exercises as if they were a choreographed ballet. Testifying to this is Beau travail’s final dance scene to ‘Rhythm Of The Night’: a fitting end to an already very musical week.

Week 3/2024

This week’s agenda features three films that are, each in their own way, profound critiques of the societies in which they are set.

On Tuesday, KASKcinema is showing Éric Rohmer’s L’arbre, le maire et la médiathèque (1993), a satirical exploration of the push-and-pull of societal progress. A socialist mayor strives to build a culture and leisure center in a small French village but finds resistance because there’s a 100-year-old willow tree on the designated field. What ensues is as a study on the delicate balance between nature and human ambition. Rohmer combines two subjects dear to his heart, ecology and urbanism, in the only film he openly conceived as “political”.

Thursday marks the premiere of Sarah Vanagt’s new video installation, De Modellen, at Kanal in Brussels. As a starting point for her new work, Vanagt took walks with twenty young women and men from Molenbeek and Schaerbeek, two Brussels neighborhoods. She engages them in conversation about the place of work in young people’s lives, their expectations, ambitions, and role models, and about personal visions of the future and a society that is changing at lightning speed. The installation will be screened alongside her previous film, De Dragers (2022).

On the same day, De Cinema is screening Agnès Varda’s Le bonheur (1965). Inspired by the Impressionist painters, Varda’s film uses their vibrant colours to challenge our perception of happiness. “The appearance of happiness is also happiness,” Varda herself said on the subject. The film shows, and therein lies its critique, that the image of happiness is already perceived as happiness. As Belgian writer and critic Eric de Kuyper wrote in 1966, “Varda talks about the clichés we live with, and she uses those same clichés to do so.” Le bonheur holds up a mirror to society by making the treacherous world of appearances attributed to ‘real happiness’ all too transparent.

Week 46/2023

However diverse, the screenings in this week’s selection share a concern with dealing with the past, its representation, its reverberation in the present, the role images play in the construction of history, their possibilities, their shortcomings.

A double bill on Monday in Art Cinema OFFOFF features Broken View by Hannes Verhoustraete, an essay film on the magic lantern and Belgian colonial propaganda. Like all media technology, this predecessor of the modern slide projector was a means to many ends and proved most effective in the construction of a colonial mindset. Exploring the tension between aesthetic experience and historical consciousness, the film attempts a deconstruction of the colonial gaze with its own construction of associations. Accompanying the film, Floris Vanhoof’s performance Fossil Locomotion, the “imaginary motion studies of my family's fossil collection”, touches the same media-archaeological nerve and offers its own perspective on the nexus between technology and historiography, technique, and poetics.

On Friday, a program in the Brussels Art Film Festival also offers two films exploring the relationship between images and history. Milena Trivier’s Algorithms of Beauty explores the limits of human perception and image technology. In 1772, Mary Delaney “invented a new way of imitating flowers” with paper and scissors. Trivier’s essay film connects these exquisitely hand-crafted flowers to the eerily similar images of flowers produced by artificial intelligence, making time fold back on itself in twenty minutes. In Deborah Stratman’s mid-length Last Things, the inanimate world takes central stage. Michael Sicinski writes, “Rocks ‘remember’ without the burden of consciousness.”

Derek Jarman’s The Last of England, a furious hymn decrying Thatcherism, screens at KASKcinema on Sunday. Jarman writes: “What do you see in those heavy waters? I ask. […] Lies flowing through the national grid, and bribery. All’s normal then? Yes. Where’s hope? The little white lies have carried her off beyond the cabbage patch.”

Week 44/2023

This week’s agenda showcases some iconic Hollywood movies that embody the pursuit of the “finished” film – a sometimes difficult and long struggle.

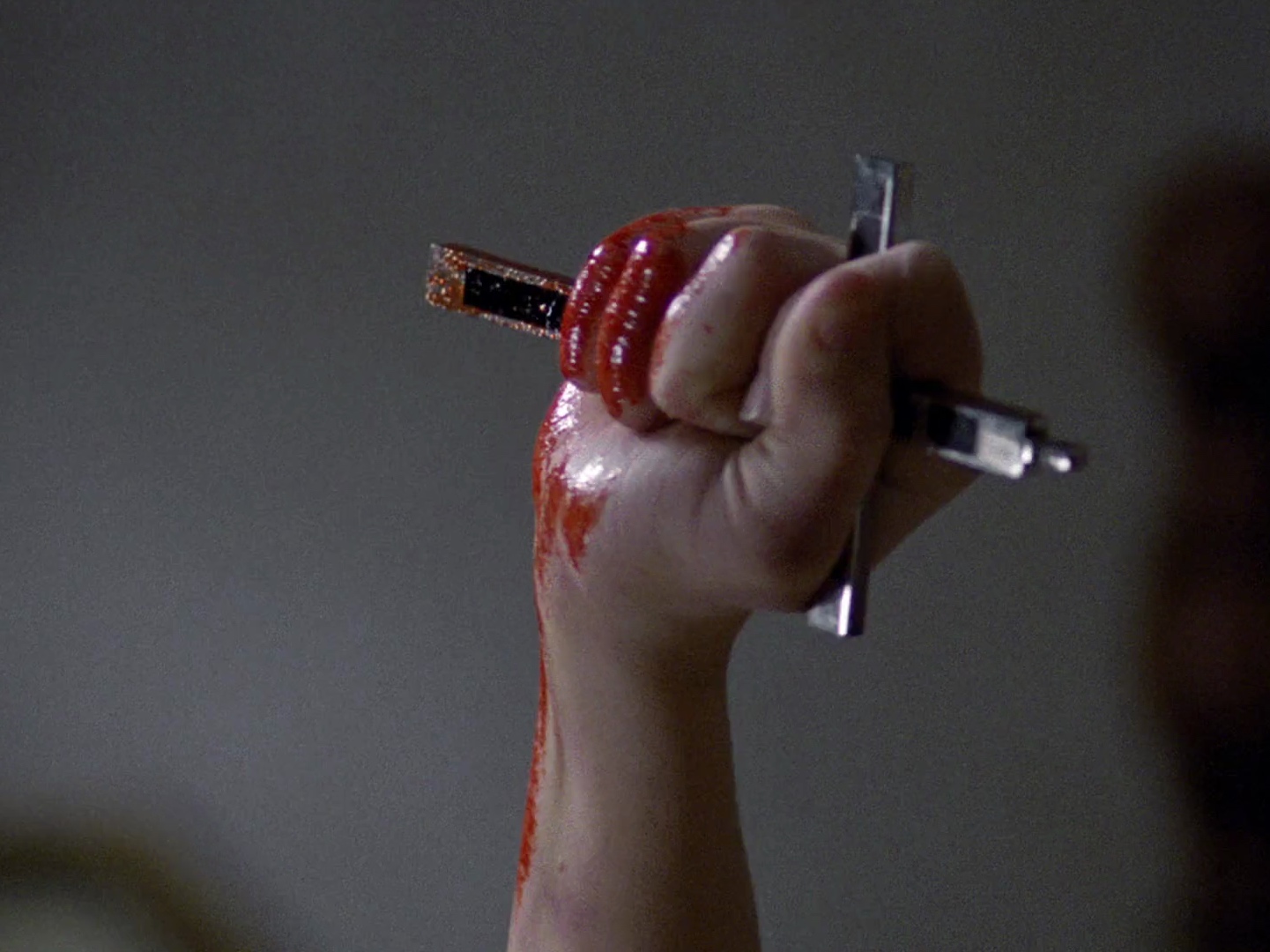

Our first film, The Fly (1986), will be shown on Halloween in its final state. However, the film initially had multiple potential endings, as evidenced from some extra material available on YouTube. Director Cronenberg interpreted the film as an allegory of aging, describing it as “a compression of any love affair that reaches the end of one of the lovers’ lives.” He added, “Every love story must end tragically. One of the lovers dies, or both of them die together. That’s tragic. It’s the end.” Apparently, some of the considered endings could have had tragic consequences of their own.

In our second feature, it’s also the ending, among other elements, that director William Friedkin altered in The Exorcist (1979). The director’s cut, released in 2000 and promoted as "The Version You’ve Never Seen," includes 10 minutes of additional footage, updated CGI effects, and a subtly modified ending. The diverse versions reflect the contrasting perspectives of Friedkin and writer William Peter Blatty. The revised ending clarifies some of the ambiguity about what truly possesses the girl in the film and somewhat reinstates the shaken faith, while the original theatrical cut left things in a more cynical light.

Our final film, famously beset by a tumultuous production, exemplifies the creative chaos resulting in multiple versions. Apocalypse Now (1979) had multiple versions over the years, even a five-hour long work print, all adding to the myth surrounding the film’s production. Martin Sheen’s heart attack, Francis Ford Coppola’s nervous breakdown, and Marlon Brando’s complex character all surely contributed too. Coppola observed that the filmmaking process mirrored the narrative’s journey, much like Captain Willard’s quest in the jungle – a search for answers and catharsis. What was changed in the 2019 final cut? It restores the previously omitted plantation scene but excludes the maligned Playboy Bunny scene featured in the Redux version.

Week 39/2023

After already re-releasing several restored features by Chantal Akerman, including Toute une nuit (1982) and Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), Cinéma Palace in Brussels is premiering the release of the newly restored Les rendez-vous d’Anna this week. Akerman’s third feature film was not shot using a traditional screenplay; instead, it was based on a remarkable 90-page autobiographical prose text. In contrast to Jeanne Dielman, Akerman worked intensively on the rhythm of dialogues and monologues, aiming for them to become like “a chant, where the actual meaning of the sentences doesn’t really matter.” Lead actress Aurore Clément will be present at the première!

Our second film of the week, Araya (1959), is a recent rediscovery of Latin-American cinema. Steven Jacobs, when first confronted with the film in 2021 at the Cinema Ritrovato festival, said that it positively blew his socks off. Margot Benacerraf’s film portrays a day in the life of three families living in one of the harshest places on earth – Araya, an arid peninsula in northeastern Venezuela. “In those days, going to Araya was like going to the moon,” she wrote. To honor this desolate place and its inhabitants, Benacerraf crafted a composition in which cinematography, music, sound, and language combine to create a tone poem of incredible beauty.

Our final film, Johnny Guitar (1954) by Nicholas Ray, hardly needs introducing. Ray’s Western about a saloon owner named Vienna and her long-lost lover, Johnny Guitar, resonates with everyone who has ever watched the film. João Bénard da Costa, former director of the Cinemateca Portuguesa who reputedly watched it more than sixty times, wrote in a beautiful essay about the film: “To revisit the images (or sounds) of Johnny Guitar is to revisit our memory of them.” “Just as with very big things, you do not explain Johnny Guitar,” he continues. “You tell it (see it) again, again and again, like stories are told to children, until everything is known by heart and you learn that everything in them is right.”

Week 36/2023

Since 2017, Lietje Bauwens and Wouter De Raeve have been researching the redevelopment of the Northern Quarter in Brussels, using filmmaking and fiction to intervene in this ongoing debate. Our first pick of the week, WTC A never-ending Love Story, picks up where WTC A Love Story, their previous collaboration, left off. The duo, co-directing with Daan Milius this time, once again mobilises actors to set up different fiction experiments, challenging power relations involved in urban redevelopment and investigating both the history and the current state of resistance in the Northern Quarter. The premiere of WTC A never-ending Love Story is accompanied by the screening of their previous film.

Staying with megalomaniac building projects, our second film of the week is Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo. Klaus Kinski, Herzog’s actor-nemesis, plays Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald who intends to build an opera house in the Amazon jungle. The scene where Herzog transports a steamship over a steep hill caused wide controversy over the years. “I’m aware of my reputation of being a ruthless madman,” Herzog responds to Paul Cronin, “but when I look at Hollywood – which is a completely crazed place – it’s clear to me that I’m the only clinically sane person there. As my wife will convincingly testify, I am a fluffy husband.”

After screening Farrebique ou les quatre saisons (1946) on Sunday, Cercle du laveu in Liège continues its September/October “Peasantry” cycle with John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath (1940). This timeless adaptation of John Steinbeck’s eponymous novel follows an Oklahoma family who is driven off their family farm and forced to join the great migration to the West during the years of the Great Depression. Despite their endless battle against capitalist forces and classist prejudice, Ford imbues his characters with grace regardless of their hardships, no doubt aided by the beautiful cinematography of Gregg Toland.

Week 21/2023

This week’s selection features a series of fantastical creations.

On Monday, Art Cinema OFFoff leads the way with a program of films by Pierre Clémenti. OFFoff invited Clémenti’s son Balthazarto present the new 4K restorations of À l'ombre de la canaille bleue (1986) and Soleil (1988), his father’s last two films. Clémenti’s hallucinatory sci-fi-noir À l'ombre de la canaille was his sole narrative feature, and it may also be his masterwork. Shot on 16mm, Clémenti’s dystopian vision of Paris is called Nécrocity, a hedonistic netherworld where state police (with the chief played by Clémenti himself) chase gangsters through hazy, heroin-fuelled nightlife.

Introducing our second film, Paul Verhoeven’s classic Starship Troopers (1997), requires a small jump to a different kind of dystopia altogether:. Although not well-received upon release, the film’s blend of genres and American TV soap-like tropes gained special acclaim in the post-9/11 era. As Verhoeven himself said, “In some ways, it's a pleasure that it all became true, but on the other hand, there's not much pleasure that it came true.”

Our last film, Malá morská víla [The Little Mermaid] (1976) by Czech filmmaker Karel Kachyna, is an adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s classic fairy tale. Unlike Disney’s recent reboot, this adaptation is most faithful to the grim morality of the original story. Known for its beautiful costume design and optical ingenuity to achieve an underwater effect, the film stands out for its musical score composed by Zdeněk Liška, who also composed music for Spalovac mrtvol [The Cremator] (Juraj Herz, 1969) and Ovoce stromu rajských jíme [Fruit of Paradise] (Vera Chytilová, 1970). Fittingly, the score was release on the Finders Keepers label.

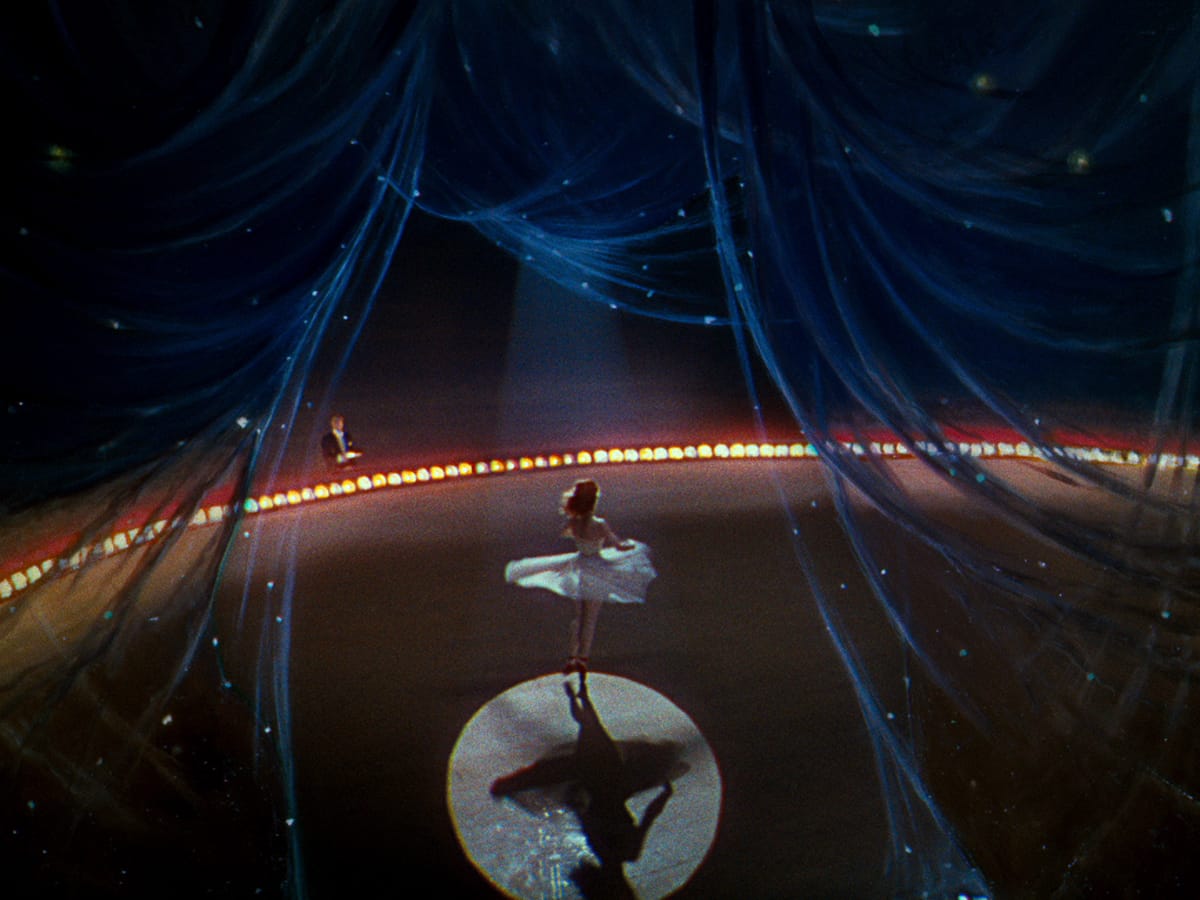

Week 15/2023

Starting off the week on Monday is The Red Shoes (1948), directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. The film follows a young ballet dancer torn between her love for a composer and her dedication to becoming a prima ballerina. Martin Scorsese, who counts the film among his greatest inspirations, once said of the film: “The ballet sequence itself was like an encyclopedia of the history of cinema. They used every possible means of expression, going back to the earliest of silent cinema.”

Fittingly, the next selected film is Martin Scorsese’s own After Hours (1985), a film that blends screwball comedy and film noir to tell the surreal story of a man’s wild journey through the streets of New York City after a chance encounter with a woman. Made in the wake of The Last Temptation’s cancelation, it remains one of Scorsese’s lesser-known films.

Also screening on Saturday is India Song, directed by Marguerite Duras in 1975, a film that defied traditional cinema with its unconventional aesthetic and anachronistic setting. The film tells the story of a married French ambassador who becomes infatuated with a mysterious woman in India. As described by Ivone Margulies, India Song is a “hypnotic chant d’amour” in which she subverts traditional cinematic techniques by using dialogue that “hangs as if in doubt, creating a sort of echo chamber where the present is continually being troubled.”

Week 10/2023

The annual Classics Restored Festival is entering its second week. From its treasure trove of recently restored films, we’d like to highlight Dolgie Provody [The Long Farewell] (Kira Muratova, 1971) and Chikamatsu monogatari [The Crucified Lovers] (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1954). And to close this week’s selection, a special screening of White Epilepsy (2012) by Philippe Grandrieux.

Although shot as early as 1971, Dolgie Provody [The Long Farewell], Kira Muratova’s second feature film, was withheld by Soviet censors for nearly two decades, only to be finally released into circulation at the time of perestroika in 1987. Calling her film an “exercise in editing” in Cahiers du Cinéma, Muratova’s films are deeply rooted in the work of montage. “If you start editing as early as I do, at a certain moment you know all the material by heart. In bed at night, you continue editing. Like a chess player who has the chessboard constantly in mind, even while sleeping.” The film was the subject of Claudio Pazienza’s State of Cinema in 2019. He praised the intimate language that runs throughout her work, describing it as: “an écriture that minutely analyses an era, the end of a world. An écriture that sees.”

On Sunday, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Chikamatsu monogatari [The Crucified Lovers], one of the films closing the festival at Buda, tells the tale of forbidden love struggling to survive in the face of persecution. Contrary to Muratova, Mizoguchi’s film style was indebted to the art of mise-en-scène. Jacques Rivette: “If music is a universal idiom, then the same goes for mise-en-scène: it is this language that should be learned to understand ‘Mizoguchi’, not Japanese.” Asked the question what he understood mise-en-scène to be, Mizoguchi replied: “It’s man! One must try to express man adequately.”

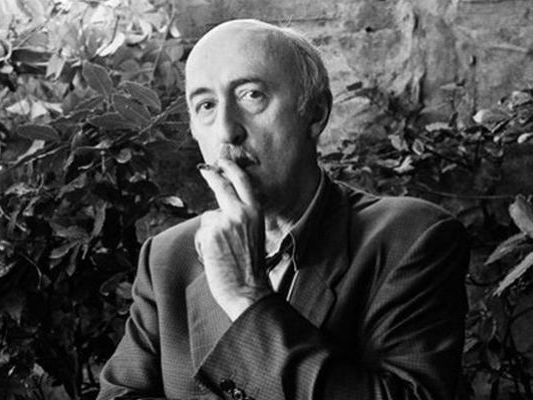

On the occasion of Philippe Grandrieux’s new staging of Tristan und Isolde by Richard Wagner at Opera Ballet Vlaanderen this month, Cinema Cartoon’s in Antwerp shows Grandrieux’s White Epilepsy on Sunday. Two of his other films, La vie nouvelle (2002) and Un lac (2009), will also be screened in the next weeks.