Bardot is Bardot is Bardot...

On four minutes of Godard

We’re given something to see.

– Serge Daney

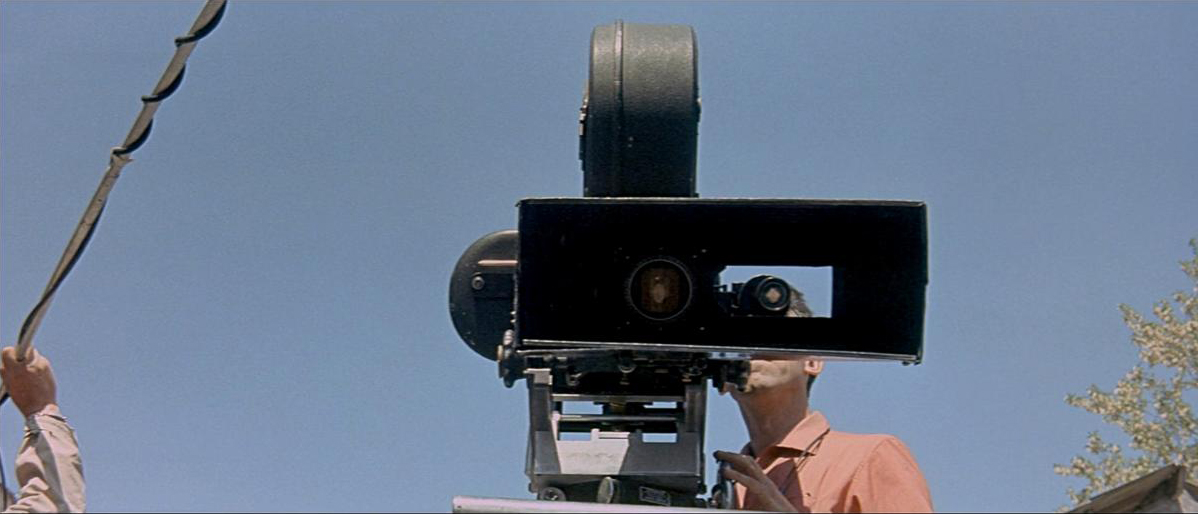

Le mépris (1963) by Jean-Luc Godard begins with a voice off dramatically reciting the credits and Georges Delerue’s ominous music. A cameraman on a dolly follows a woman walking in our direction while browsing a notebook. At the end of the credits, the only thing we’re still seeing is this camera, sideways, like some kind of big cannon. Making a quarter turn, it rises above our heads, until it lowers and gazes at us like a giant, open orifice that could swallow us, that in fact has swallowed us already, because we don’t realise that we already are only seeing what this blank, cyclopean eye gives us to see, that our gaze is pulled into a peeping box where everything we see is given to us in order to be seen.

The music ends when the credits end. A woman (Camille, played by Brigitte Bardot) is lying on her belly, naked, on a bed next to her lover, who is dressed (Paul, played by Michel Piccoli). She’s facing him. The room is bathed in a red glow. Because the light is coming from the left, Bardot’s head is casting a shadow onto Piccoli’s face. “I don’t know,” she says. She seems bored. Piccoli’s posture also suggests boredom. When the dramatic music resumes, we are suddenly in another world. Bardot asks: “Do you see my feet in the mirror?” “Yes,” Piccoli answers. “Do you like them?” “Yes.” Apparently, an offscreen mirror to the left allows her lover to admire her. She asks him if he loves other parts of her body as well: ankles, knees, hips, buttocks, breasts, and some body parts that are not visible in the mirror. He cannot but answer affirmatively. When the music stops the room is suddenly filled with yellow light, as if someone has abruptly opened a curtain. The music immediately resumes and Bardot proceeds with the enumeration of all her attractive body parts. Fully exploiting the horizontality of the CinemaScope format, the camera slides over her body once. When it reaches her face again, she asks: “And my face?” As soon as she starts enumerating all the parts of her face, the room is bathed in an unreal blue. Paul says he loves everything equally. “Thus, you love me entirely?” “I love you entirely, tenderly, tragically.” “Me too, Paul.”

In this scene of minimal narrative importance, squeezed in between the credits and the actual beginning of the film, the woman doesn’t have a name yet, but everyone recognizes her as ‘Brigitte Bardot.’ This ‘Bardot’ is not the person ‘behind’ the actress, but an equally fictional character, namely the woman moulded by the mass media (tabloids, television, cinema…) into an icon of sensual beauty and sexual freedom, provocative as well as naive, through her naked appearance at the beginning of Et Dieu...créa la femme (Roger Vadim, 1956) for example. The opening scene of Le mépris is a kind of paraphrase of that scene.

Godard doesn’t even consider turning Bardot into a character shattering the stereotypical image the mass media make of her. He presents Bardot as ‘Bardot’. He cites the phenomenon Bardot, uses it as a kind of ready-made, without irony. And because the mass media associate the name Bardot with ‘nudity,’ he promptly presents her naked. It is as if Godard is saying to the audience: “You came to watch a film with Bardot? Here she is in her entirety, totalement, naked like Urbino’s Venus.” Using camera work, lyrical lighting and compelling music he lets her iconic beauty appear in all its glory, boldly, directly, unrelated to any action, without any typical narrative pretence (bathing, dancing, sunbathing, taking care of her body, getting out of bed…), and also without pseudo-naive coquetry or ‘suggestive’ poses. No, this is not a slice-of-life scene; it’s a scene clearly made for us. The abruptness of Bardot’s naked appearance points at this. The nudity we’re served is unannounced; it’s as if her body pops up out of nowhere. Throughout the entire film Bardot will moreover never transform entirely into the character Camille. Her celebrity status will keep radiating from her character.

Bardot doesn’t see herself in the mirror she uses to ask her lover to look at her and admire her in. She only knows she’s in this mirror; she knows she is beautiful in it. That the mirror remains out of sight is understandable. After all, it represents a mirror that is essentially invisible, the mirror of film as a medium not seldom displaying female beauty, and more broadly the mirror of the mass media film is a part of, the mass media that since the 1950s ever more obtrusively and vociferously colonize our lives and that endlessly milked Bardot as an icon. For us this mirror is equally invisible; we can only look in it.

That we can’t see this mirror doesn’t mean this intimate scene isn’t an allegory of it. The scene allegorizes the way this mirror plays on our desire. The bedroom scene immediately succeeds the credits that end with a short quote: “‘The cinema,’ said André Bazin, ‘substitutes for our gaze a world more in harmony with our desires.’ Le mépris is a story of that world.” We are warned: while film usually plays on our desires, this film will lay out how this is done. Is it the sobering, ‘disenchanting’ unravelling of the medium? Doesn’t this scene with a naked Bardot use all means to dazzle us? Yes, it does, but that’s not concealed from us.

The shadow over Piccoli’s face shows us something we can never see, namely our own gaze. Even if he is her lover, just like the anonymous cinemagoer, he’s sitting in the dark looking at the beauty of what Bardot is showing in the mirror behind her. Looking in the invisible mirror, he’s, like us, the passive prisoner of the medium, willingly without willpower. His obscured gaze allegorizes the fissure between who is looking and who is in the frame. Piccoli represents the film audience that is supposed to enjoy, from a distance and thanks to this distance, this distance enabling everything to be seen and recorded for the first time in history, far more than one could, would dare or even would want to see and record in real life. Like Perseus was able to obtain Medusa’s head only because he didn’t look at her directly but watched her in his mirror instead, film allows us to access everything because we do not actually reach it, we only take an image with us. This cunning, shameless, professionally organized theft constitutes the often praised ‘magic’ of cinema. Cinema is often accused of fragmenting the female body through camera work, actors’ direction and lighting and consequently of reducing it to a collection of fetishes concealing a woman as a person. When Bardot enumerates her pretty body parts one by one and asks her lover if he loves these, it’s as if she herself offers her body as a totality of fetishes.

What does a fetishist do? He idealizes a woman. He elevates her to a perfect being who’s capable of satisfying him entirely. He knows very well she is not able to do this; but in order to renounce this truth, he elevates a part of this woman or something in her surroundings to an ideal object: a foot, a garment, or something ‘immaterial,’ like a glance, a shiny forehead, a tic. For him, this single aspect signifies the untouchable perfection of this woman. Nudity being a taboo, classical Hollywood films incited a fascination for and a kind of collective cult revolving around a particular characteristic of every female film star. This characteristic became their hallmark. Eric de Kuyper recites some of them: the legs of Marlene Dietrich, the glance of Lauren Bacall, the back of Kim Novak… Because his attention is caught by these ‘typical characteristics,’ the spectator is trapped by the image and thereby cast out of the story but also unconsciously motivated to follow the story, how ridiculous or clichéd it may be. Strictly speaking, the fascination for such a typical characteristic is not fetishistic. The fetishist adores a part or an attribute he, as it were, cuts off or away from a woman. The unique characteristic on the other hand is not isolated from the total image. It unemphatically colours a woman’s entire appearance and gives it an aura of sovereign inapproachability.

In the bedroom scene, the camera doesn’t fragment Bardot’s body. The fragmentation happens only verbally. Moreover, it’s induced by the woman herself who lists her body parts one by one and in so doing discourages all fixation. In words, she scans her entire body for her lover and the audience. This explicit verbal fragmentation of a body left intact as an image stands in sharp contrast to the way the camera fragments the female body in music videos for example, ‘provocatively’ zooming in on body parts, usually less than a second, so that buttocks or breasts are hitting the eye rather than offering themselves as a passive object to the gaze. Bardot gives the spectator some time to look at her and enumerates calmly what there is to see. Because the body parts are named, they are virtualized, as if what you think you’re seeing is only an image announcing or promising an actual appearance. The nudity that’s displayed becomes a kind of veil, hiding something. Words that identify do not show, they cause the gaze to not entirely believe what it sees and consequently to grope for something invisible. Bardot, by the way, also names body parts we don’t see, like her knees and breasts.

Bardot’s diction is rather expressionless, reciting almost mechanically. Her questions don’t sound hysterically at all, in the sense of “Do you really love me?” They sound indifferent. These are the questions of a woman who is at ease, who knows that she is beautiful and adorable and that her lover will answer affirmatively. He doesn’t answer in the sense of “But of course I love you, you know that, don’t you?” He articulates the obligatory “yes,” the answer already included in the question. This is not an emotional confrontation between two characters. All psychology is lacking. It’s a private ceremonial. Maybe these two are repeating a dialogue that once developed spontaneously. Maybe they are playing a game they have played before, a game that's only entertaining when played really seriously.

The indifferent, recitative tone accentuates the absurd logic of the dialogue: you love my feet, ankles, hips and so on, thus you love me entirely. It’s not absurd that Piccoli loves all Bardot’s body parts, nor that he loves her in her entirety, it’s the connecting ‘thus’ that is absurd. Bardot dispassionately suggests an uncomplicated continuity between her beauty and sexual attractiveness and the unnameable about her that causes her lover to love her, as if you only need to put her parts together in order to obtain a harmonious totality worthy of the love of her lover. It’s as if Bardot with this enumeration and absurd ‘synthesis’ is parodying the Greek beauty ideal with cool irony – in this film, revolving around a film adaption of the Odyssey, Greek statues are popping up frequently – and at the same time alluding to the mass media that constantly take apart and reassemble her body.

According to Jean Baudrillard, an advertising slogan from the 1960s epitomizes how publicity interpellates women: “The body you dream of is yours.” The explicit message is: “You deserve the body you have been dreaming of for so long, that’s why we give it to you. Grant it to yourself.” The implicit message is: “You yourself have to earn what you deserve. You have to work for what you are naturally entitled to. Only when you take care of your body with our products, and thus manage it well, you will get the body you have been dreaming of for so long.” While the explicit message suggests an immediate, magical wish fulfilment, the implicit message points at the necessity of labour, discipline. Only the explicit message applies to Godard’s Bardot, stretched on the sheet. She is the goddess who effortlessly obtained the body the media make every woman dream about. That dream body is a magical gift of which she is the gifted receiver. When Bardot invites Piccoli to declare his love for this dream body, she acts that there’s nothing she wants more than to be seen and loved by him as this body, as if she is the happy prisoner of the dream the media make women dream. She acts that she coincides with the image appearing behind her back, in the invisible mirror. She plays that she has merged into this split off image, that she’s disappeared into it and that she expects from Piccoli that he affirms her. “I have become All-Image, in other words Death in person.” (Roland Barthes) Piccoli plays along, like Bardot, he’s not suspecting some truth is at work in this game. This unsuspected truth is not only to be seen in the shadow over Piccoli’s face, but also to be heard in the sinister music they don’t hear. Piccoli is our equal, our double in the affirmation of his love for Bardot, assembled into a beautiful totality in the mirror. He has yielded his lover to the medium that turns people into ossified icons, for example into stereotypes of ‘liberated, uncomplicated sexuality.’ Inside the idyllic privateness of this heavenly radiating bedroom he already has lost his wife, because he sacrificed her to her image. Godard was obsessed with the gloomy, obsessional painter of Poe’s The Oval Portrait, who succeeds in painting a perfect portrait of his beloved wife: he captures not just her figure, but her vital force. When the painting is finished, he realizes that all her vitality has been transferred to the canvas. His wife is dead.

The opening scene of Le mépris doesn’t merely show us an image of Bardot, we’re actually seeing something there’s no image of, namely how Bardot is made into an image. The abrupt, unannounced aspect of her naked appearance at the beginning of the film, the mirror she talks about, Piccoli’s obscured gaze that is ours too, Bardot’s laconic enumeration of her body parts – all this forms an allegory of how Bardot becomes an image and gives us a feeling of unreality. This tableau of an intimate, amorous encounter isn’t presented to us as something we witness by chance but as a scene manufactured in order to be presented to us. This feeling of unreality is reinforced by the theatrical, hyper-artificial lighting. Bardot’s body is first immersed in romantic red light, then in radiating yellow light, finally in mysterious blue light. This change of lighting gives the impression that the uninterrupted shot appears anew every time, as if Bardot’s naked, sudden, ‘magical’ appearance ex nihilo after the credits repeats itself.

The spectator feels he’s not just seeing what he wants to see, but only what is shown to him, what is staged for him. The changing lighting both glorifies Bardot’s body and reveals the mechanism of this glorification. Artificially clad in lighting, this body becomes smoother, more flawless, excessively disposed of its fleshiness, like a smooth sculpture. It’s obviously not meant to be touched. Bardot immediately fends off her lover when he tries to hold her for a moment: “Not that firm, Paul.” The body is an image and appears like that: as something deposited in a peeping box, outside the world. But this is cinema. The image stays intertwined with this body, this breathing, lightly surging body of which we know that it exists in the world and belongs to a human being. The body here has become an image of itself.

In conjunction with the theatrical lighting, the overwhelming soundtrack contributes to the glorification of Bardot’s beauty. It helps the spectator to ‘elevate’ a sexually attractive body to a body that affects us aesthetically. The rhetoric of this elevation is very present. Like the changing lighting, music is also artificially poured over the tableau. This is most obvious when it breaks off and subsequently starts again. In this way the shot is broken in three. When the music starts, an anecdotical, rather bored conversation that mentions Bardot’s mother is transformed into the more ceremonial, impersonal recitation that combines Bardot’s attractive body parts into an adorable whole. When the music suddenly stops in the middle of the shot, you become aware of the fact that the music pumped in the feeling you experienced while watching the scene. You experience this also when the music starts again. You experience how you get thrown out of your emotion and back in. You experience how your emotions are manipulated, how easily this is achieved. And this way an irony creeps into your emotions. This doesn’t take away your emotions, but rather seasons them with the melancholic feeling that you can’t really seize your own emotions, as if you find yourself in a space where your unseizable emotions are roaming about. This scene is enveloped in a mist of melancholy, as is the entire film. For Godard, cinema has had its day. It’s like he says: “I’m celebrating a female star for the last time, using all cinematographic means, drenched in beautiful colours and overwhelming music. I’m showing her to you and I show you how this is done.”

The tragic, ominous sounds contrast with the light-heartedness of the dialogue. They’re floating above it. These sounds thus most likely point at a future the lovers are unaware of. They make the audience feel something the protagonists don’t feel yet, namely that the end of their relationship has already ushered in. Only at the end of the dialogue it seems Piccoli is seized with the emotions voiced by the music, namely when he answers Bardot’s question if he ‘thus’ loves her in her entirety: “Yes, totally, tenderly, tragically.” But it seems Piccoli has been carried away by the solemn, sehnsuchtig rhythm of the music rather than that the music expresses his feelings. His character, Paul, is like an actor in a film about a tragic love affair. In this sense, he’s tragicomical.

The so-called simplicity, the ‘directness’ of the image is always an inevitable illusion: the image presents things as identical to themselves but holds back that this identity is an illusion existing only in the image, as a duplicate. The image withholds itself. It withholds that what it shows doesn’t exist in any world, it only exists in what the image itself shows. The image is deceptive in that it presents itself as a re-presentation, in that it pretends to show something that existed before, as if the represented is not always already given to us in order to be seen, as if its appearance is not always already framed through the ways in which it has already been described and imagined before, with all of the mise-en-scène this brings with it. Before an image has been made of it, a thing is always already tilted in its similarity. Think of Gertrude Stein’s “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose”… You can interpret this as: you shouldn’t want to define or describe a rose, the existence of the rose should remain a secret forever and thus you will never get past its name that will remain a meaningless chiffre, comparable to the biblical God who can only say that he is that he is. But doesn’t the repetition of self-identity reveal that it never belongs to itself, that every postulation of this identity is an incantation of an internal difference?

Bardot is Bardot is Bardot... Everywhere she went, her name, her persona, her logo had preceded her, turning her into a kind of hallucinatory stand-in of herself. The bedroom scene shows us this unreality, a woman unabashedly letting herself slide into her stand-in, over and over again clad in different lighting and with majestic music poured over her. This woman is no rose. Light-heartedly and frankly acting as if all her beautiful parts together form her – adorable – ‘identity,’ playing that she coincides with her image, she reveals her radical self-difference, namely that nothing of all that is said and imagined about her actually applies to her.

Images from Le mépris (Jean-Luc Godard, 1963).