Partners in Crime

Interview with Dion Beebe, cinematographer of Miami Vice

From a material standpoint, cinema was at a tipping point in the late twentieth century. Digital cameras were improving, evolving into a palette of choices. Companies such as Canon, Panasonic, Sony and Thomson Multimedia developed professional, semi-professional and non-professional cameras, from Mini DV to high definition digital video. The emergence of video was initially accompanied by much skepticism and the renewed declaration that cinema, the art supposedly inextricably linked to the twentieth century, was dead and buried at the beginning of the third millennium. Cinema and celluloid seemed to be synonyms; the digital a “different” medium. Not surprisingly, the first professional digital cameras were initially developed to reproduce the look and feel of 35mm celluloid. Technical efforts were made to suppress the digital look, often by using coarser grain and specific lenses. One of the selling points was that it could reduce the expensive celluloid costs. The result was not infrequently nostalgic. Filmmakers who were working with a digital camera were looking for a cinematic image from the past.

More than twenty years later, much has happened in the development of digital cameras. The initial suspicion seems to have disappeared and filmmakers are making a more casual choice about whether to shoot digital or not. After all, celluloid has not been put away forever either; even Hollywood makes frequent use of it today. Examples abound: from Christopher Nolan’s Tenet (2020) and Patty Jenkins Wonder Woman 1984 (2020) to the latest James Bond film, No Time to Die (Cary Joji Fukunaga, 2021). Today, the choice of format is also less decisive. The major material differences between digital and celluloid are negligible to inexperienced viewers. At the turn of the century, things were different, and a number of filmmakers then took up the task of exploring the digital as digital, as a material with its own pleasures and aesthetic value, against any nostalgia for twentieth-century celluloid-only cinema. Some well-known examples include Pedro Costa’s No quarto da Vanda [In Vanda’s Room] (2000), Jean-Luc Godard’s Eloge de l'amour (2001), David Lynch’s Inland Empire (2006), Wang Bing’s Tiexi qu [West of the Tracks] (2002), Agnès Varda’s Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (2000), Michael Haneke’s Caché (2005), Richard Linklater’s Tape (2001), Abbas Kiarostami’s ABC Africa (2001) and Dah [Ten] (2002), and Steven Soderbergh’s Full Frontal (2002).

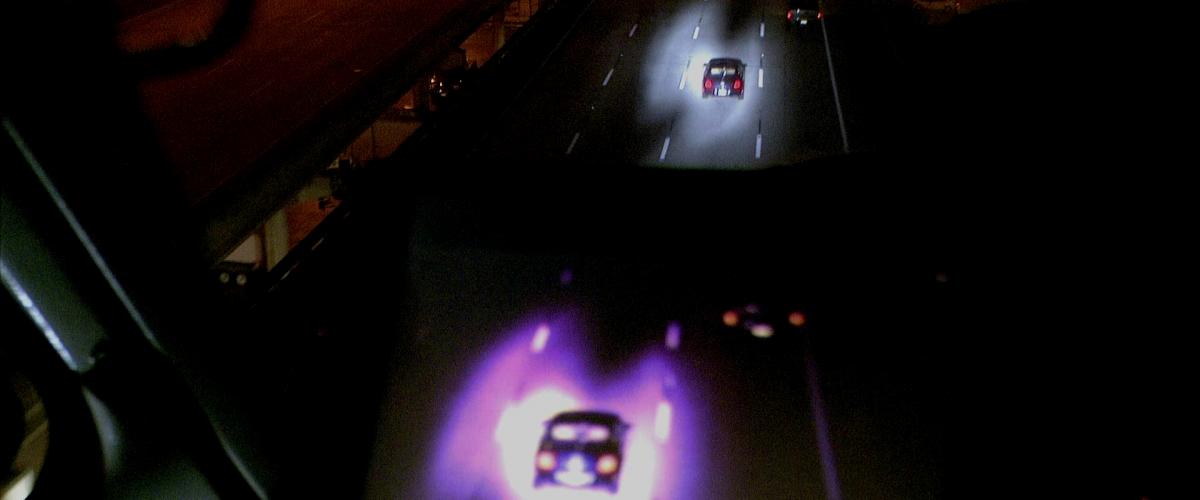

American filmmaker Michael Mann, known for Thief (1981), Manhunter (1986), Heat (1995), Ali (2001) and Public Enemies (2009), was one of the first filmmakers working in Hollywood to embrace the digital. After earlier experiments with high-definition digital video in Collateral and Ali, Mann resolutely opts for the digital format in his 2006 Miami Vice. The result is an action movie that is not only driven by plot and spectacle but is just as much a plastic work, characterized by the grainy texture and colors of the first HD cameras. On the occasion of the screening of Miami Vice organized by Sabzian at Cinema Galeries on the 25th of November, a number of texts will be published around the film in the coming weeks. In this interview, Miami Vice’s cinematographer Dion Beebe explains that the choice of digital came not from practical concerns but through an experimental search, guided by Mann’s intent of the film. From their experience with Collateral, they discovered the aesthetic possibilities of the digital format in night shooting: “Certainly when you look at it on screen, the format is different from film. It’s a different result. Because you’re seeing a night world that is richly illuminated, with an enormous amount of depth, it’s slightly unsettling. It feels almost otherworldly, and it’s somehow a little bit alienating. I think that works so well with the storyline and with the journey of these two characters in this cab, because it becomes this alien landscape. You’re left with a different impression, certainly, than if it were shot on film.”1

For Miami Vice, the question arose as to whether digital also held up well enough in daytime shooting. Michael Mann, Beebe and his team tested every format available at the time to determine which best matched what they were looking for aesthetically. That’s how they ended up with the GrassValley Thomson Viper camera, combined with Zeiss HD lenses. The filmmakers loved the great depth of field and texture, the wide range in blacks and how the camera surrendered to different lighting situations. It gives Miami Vice a unique digital look typified by an impressionistic color palette – from the dingy yellow-red of the Miami highway to the bright blue light of ports and warehouses. As Jean-Baptiste Thoret writes in his latest book on the cinema of Mann: “The grain of the image, the heightened sensitivity to light that reveals, in the darkest areas of the shots, an infinite variety of tones, these lightning bolts that zap the Miami sky and give it an evocative power close to pictorial romanticism, or this greasy, incandescent night that permeates everything, provide the feeling of a sensualist, almost dreamlike film, where man, nature, and urban environments vibrate with a single breath.”2

This interview contains at times very technical information but is important as a document because it captures this specific moment in film history. It bears witness to this turning point where digital cinema still had to come to terms with itself, still had to start believing in its own possibilities. It is to the credit of Michael Mann and his team that they took on this task in an unforced and experimental way. This interview also tells the story of a period when the digital still showed itself to be digital, and was still recognizable to that extent. That is what is so special about Miami Vice and the makership that lies behind it: the digital is approached as a material. But Mann’s Miami Vice is more than a style exercise; the aesthetic possibilities of the digital are brought into play to describe a new globalized and connected world, defined by overvisibility, surveillance and intangibility. Oscillating between “hyperrealism and impressionism” (Thoret) and starting from the rules of the genre film, Miami Vice seems to be driven by both a fascination and a distaste for late capitalism, with Mann using a new cinematic technique to make the spectator a witness to the process of a contemporary world and its forms.

Gerard-Jan Claes

Miami Vice undercover cops Sonny Crockett and Ricardo Tubbs are back, and for their feature-film debut, they have been given a facelift by original series creator Michael Mann. The days of high-fives in fast cars and zipping along in speedboats with bikini-clad babes are over, and the film finds our heroes struggling with moral dilemmas amid a gritty, hard-hitting crime drama.

Miami Vice undercover cops Sonny Crockett and Ricardo Tubbs are back, and for their feature-film debut, they have been given a facelift by original series creator Michael Mann. The days of high-fives in fast cars and zipping along in speedboats with bikini-clad babes are over, and the film finds our heroes struggling with moral dilemmas amid a gritty, hard-hitting crime drama.

Miami Vice was photographed by Dion Beebe, ASC, ACS, a recent Academy and ASC award winner for Memoirs of a Geisha. Beebe first teamed with Mann on the thriller Collateral, which was the cinematographer’s first foray into high definition (HD) digital video. For Vice, Mann and Beebe returned to HD, shooting most of the action with Thomas Grass Valley Vipers, Sony CineAlta T950 CCD Block Adapters, and Sony CineAlta F900s.

“We went back down the digital path, but we weren’t looking to reproduce the look of Collateral,” says Beebe. “We used the experience we gained shooting nights on Collateral to develop the night look on Miami Vice, but this picture has a very different look. We went for more contrast with hard light, as opposed to the soft, wraparound look we did on Collateral. We also had to deal with daylight, which was a new challenge for me in HD.”

Before the filmmakers decided to use HD, they spent months testing the digital cameras alongside film cameras to see which would give them the best shot at the look they had in mind. “We wanted to satisfy ourselves that what we could achieve in digital was not something we could simply produce on 35mm film,” explains Beebe. After investigating a number of negative stocks, he settled on two in Kodak’s Vision2 family, 50D 5201 and Expression 500T 5229, and all test comparisons of film and HD were done against the two stocks to maintain a control base.

“We found once again that where HD really stood out was in night work,” says the cinematographer. “We also decided there were attributes of HD technology we liked and wanted to exploit, like the increased depth of field. Because of the cameras’ chip size [2/3”], they have excessive depth of field that we decided not to fight, but rather utilize. In addition, because we were already in a digital format, we elected to push the image even further in color correction to really refine the look. Through the testing process, we found a look we loved with HD.”

“Hi-def already stands out for its incredible sensitivity in the low end,” he continues. “You are able to create files that really extend this end of the sensitivity curve, enabling the cameras to really dig into the shadows. The perfect example of this is shooting at night and actually capturing details in the night sky, which is something that film, shooting at 24 fps with a 180-degree shutter, just can’t do yet. Early on in the testing, we shot a daytime sequence that involved some stand-ins against a brilliant blue sky with beautiful cumulus clouds. When we took that footage to Company 3 and worked with [colorist] Stefan Sonnenfeld to apply the look we already set, the image just popped off the screen – it was almost like a 3D effect. The result was a combination of the increased depth of field, the exposure settings, color timing, and something in the nature of the medium itself. The clouds and the people were so vivid it really excited us. It’s not necessarily something you’d identify unless you were looking at film and digital side by side, but this was the kind of effect we were looking to achieve.”

The filmmakers also tested Panavision’s Genesis camera against the Viper and Sony CineAltas. “The Genesis is a fantastic camera, but it shoots in the uncompressed mode and you can’t do any manipulation on the set, which is something Michael really likes to do,” says Beebe. “So it wasn’t in the running for us.”

In terms of lighting, Beebe went for a hard, contrasty look. “Michael and I discussed a chiaroscuro, hard-light style, and we mainly achieved it with undiffused single-source lighting that created strong shadows,” he says. “That in itself was a departure, and we went further to develop a look with Stefan, to really push for a higher-contrast look with a stronger color palette than we had on Collateral.”

“The HD cameras have less latitude in the highlights than film, and that was a tricky part to negotiate,” he continues, “We had to find a daylight look that was bold and interesting but would ultimately work to protect our highlights. Summer in Miami is a variety of extremely bright sun, haze and heavy clouds – very trick situations exposure-wise. The most challenging situations were when we were shooting day interiors against very bright exteriors. We had one interior location looking out on Biscayne Bay with huge, floor-to-ceiling windows and open doors. We had set a mandate with our exposure that we worked from the background forward. This meant exposing for low ambient light for our night work and lighting to that stop or, in this situation, exposing for our highlights and then bringing the interior up to meet the exposure set for the exterior. When possible, I tried to work within a 1- to 2-stop latitude between the highlights outside and the key light on the actors. With film, I could easily have made that a 3- or 4-stop latitude, but with the digital cameras, two was the most I would do, and for our look, it seemed the best approach.”

That required a great deal of light; lighting actors to a T22 to match exterior highlights is no small feat. For the Biscayne Bay location, Beebe positioned three 18K HMIs about 12’ from the actors to get them within one stop of the exterior highlights. “It’s certainly not ideal for a cinematographer to put lamps that close to actors, but my back was a bit against the wall with the look we had set. Because we had open doors in addition to big windows, there was no way to put any kind of ND [gel] on the windows. We used a heat shield in front of the HMIs, and there was also glass between the fixtures and the actors, but still wasn’t ideal, because you want to protect the actors and their environment as much as possible.”

HD cameras are, of course, capable of more latitude than a single stop, “but the way we were setting the menus, the way we set our look for the final transfer to 35mm, and the way I wanted to hold the highlights outside, I found one stop of high-end latitude was as far as we wanted to go,” says Beebe. “It’s pretty common knowledge that you have to protect your highlights with HD. Once something peaks, it’s gone, and there’s no getting it back.”

Mann’s shooting style often requires rolling multiple cameras simultaneously, and the production carried a veritable army of HD cameras. The picture’s look was set with the Viper, which the filmmakers preferred to use whenever they could. One of the main reasons for that is the Viper’s ability to record a native 2.37:1 image with standard spherical lenses without any loss in image resolution. (The 1.78:1 CineAlta image must be cropped to achieve the anamorphic aspect ratio.)

“Michael likes to make adjustments in the camera, whether that be a percentage of desaturation of just the reds, or adjusting the gamma,” notes Beebe. “We could often do those kinds of minor tweaks before we rolled.” Just as on Collateral, the Viper was set to VideoStream (RGB) mode so such adjustments could be made on set. In the uncompressed mode, no internal signal processing is possible, because the RAW data from the camera’s three CCDs is transmitted directly to the recording device; in VideoStream mode, the camera’s full processing menu is available to manipulate the image. The output is 4:4:4 dual-stream HD-SDI in 22-bit RGB data. This data was then recorded to Sony HDCam SR SRW-1 decks at 4:1 compression.

Once a look was settled on, scene files were created and recorded to adjust the CineAlta cameras to match the final look set by the Viper.

There were limitations to the Viper, however. “The cameras aren’t really designed for field use, and we built on modifications we’d made them on Collateral to modify them further,” says Beebe. “Referring to specific requirements from [A-camera operator] Gary Jay, we worked to make the Vipers more robust and suitable for the style of filmmaking Michael likes, which is a lot of handheld work. In a Michael Mann movie, someone is always holding the camera, and that puts a lot of wear and tear on the gear.”

“During prep, we were in the machine room at Plus 8 making rigs to try to offset the weight of the camera, which is very front-heavy, by displacing the battery off the back,” he continues. “We actually ended up creating an aluminum casing for the Vipers, which also stood to protect the body and make them much more robust. We knew those cameras were going to be running around in a lot of exteriors, heat and humidity, on boats, in cars and in jets. They had to be ready to take the punishment.”

Although the production tested recording options such as the Thomson Venom FlashPack and the S.two portable record drives, they eventually decided to stick to the Sony SRW-1 decks, which also stood to form a common denominator with the CineAlta T950s. “At this early stage of this technology, there are only a few various workflows for shooting HD for an eventual film-out,” explains Beebe. “[Producer] Brian Carrol created our workflow, choosing recording to tape over hard drives. Even if we had gone with hard drives, we most likely would have had to back up all our material on tape anyway, so we elected to go with the decks and forgo the drives altogether. This meant that with the Viper, we were always tethered to the mothership.”

Beebe’s “mothership” consisted of a video village that housed a rack of three HDCAM SR SRW-1 record decks (to record up to three cameras simultaneously), waveform monitors and 27” HD monitors. There was also a custom look-up table (LUT) box that was programmed with a series of LUTs set to emulate the final look of the film print. Beebe worked with three main settings, one for daylight and two for night looks. These looks were not recorded to decks, but were applied to the HD monitors.

Although a lot of work went into refining a fiberoptic tether for the Vipers, “we had varying success with the fiber lines and had to resort to the larger copper lines quite a few times,” says Beebe. “Trying to get the fiber lines working was pretty much an ongoing research-and -development process. In either case, the cameras were always tethered, but we knew that was going in and carried the Sony cameras to fill in when we needed to disconnect.”

“We were usually running three cameras at a time, and we often wound up mixing cameras because one [Viper] couldn’t be tethered for one reason or another. Whenever we could, we tried to run three Vipers, but that depended on a lot of factors, not least of which was our setup time. Setting up three Vipers meant running three tethers to the mothership, and that took time, unlike having someone grab an F900 that can go wherever. Nevertheless, the Vipers were our preferred choice, and we tried to stick to the discipline of tethering them up whenever possible. Our digital crew, led by Dave Satin, worked tirelessly to keep the mothership running and the cables run for all three Vipers through some very difficult locations; we were often running fiber cable in excess of 100 feet.”

Deciding when to incorporate the CineAlta cameras was purely a logistical matter. “If we were in run-and-gun mode or had to put a camera in the front seat of a Ferrari or the cockpit of a powerboat, we would go with the T950,” says Beebe.

The T950 is a modification of the HDC-F950, and the camera’s imaging system can be separated from the body and processors by up to 50 meters. This allowed Beebe to use a very compact and lightweight camera head with a short cable to the body and portable SRW-1 record deck (which ran on batteries) to fit the T950 into tight spaces. “That solved the problem with the size of the cameras, but the afterthought was always, ‘Now, how we do fit the operators intro these spaces? Gary [Jay] is over 6 feet tall!” says Beebe. “Gary and the other operators, Duane Manwiller and Niles Roth, worked hard to take these cameras into places they’d never been before, and they did great.”

During prep, the production filmed out footage from all the HD cameras it planned to use. “We knew what we had to do to ensure the pictures would match,” says Beebe. “With the way we were setting our exposures and processing the image, the 3:1:1 of the HDCam deck on the F900 wasn’t a problem against the 4:4:4 Vipers. Being able to choose from among the Viper, the T950 and the F900 allowed us the necessary flexibility to cover any situation. We were always shooting with a least two cameras, and we worked in a third whenever possible.”

“We were always assessing the placement of the cameras, discussing how they’d integrate into the scene, and finding ways to light around them,” continues the cinematographer. “There is ultimately no clear, single solution to shooting with three cameras; you’re always working on the fly and adapting to each situation. Sometimes Dave [Satin] was making adjustments to the iris on the fly to compensate for lighting changes, but I was always looking for ways to protect all three cameras. I found no real textbook approach to it. Michael’s style is very dynamic, and the tension he creates is due partly to the unpredictable nature of how the cameras are placed and how they move in relation to the actors.”

“This is all further complicated by Michael’s blocking of the actors – they are seldom static. We were rarely, if ever, in a situation when we could just double up camera coverage, with one camera close and another wide. The A camera might start on a close-up of one actor, but as the scene progresses, that actor will move to another area and the A becomes a two-shot while the C [camera] becomes that actor’s close-up for the next part of the scene, before he moves again and the B camera picks him up in a close over-the shoulder. It’s very organic, but also very considered. Michael is very precise with camera placements and compositions, and he creates tension not just through movement, bus also through a refined composition and placement of actors and objects within the frame. There were very specific frames and compositions that we would lock on, and those would lead the process. It’s quite hard to describe, honestly. Michael is very, very specific, but at the same time he lets the scene develop. At the end of the day, he wants coverage to feel as real as possible.”

Throughout the shoot, Beebe worked almost exclusively with the new Carl Zeiss 6-24mm DigiZoom, even though he also carried a set of Zeiss DigiPrimes. “We pretty much lived on the DigiZoom, and it was a great tool for us. Michael really likes to utilize the zoom for specific emphasis, especially with handheld cameras. DigiZooms were on the A and B cameras almost all the time.”

Although the majority of Miami Vice was shot digitally, the production used 35mm film cameras, Arri 235s and 435s, for high-speed and underwater work. The team discovered they also had to use film cameras in order to work with a specialized lens for some very close shots. Beebe explains, “Michael likes to work with the Frazier lens system to get very close to the actors. We weren’t working with Panavision cameras, so we went with the [P+S Technik] T-Rex SuperScope lens system. When we fitted the T-Rex to the HD cameras, we noted a significant loss of light that didn’t make sense. There was some anomaly with the optics of the lens system and the HD cameras that made them incompatible. Through the heat of battle, we never really got a clear answer as what was happening, so we simply used film cameras to shoot all off the T-Rex work.”

On Collateral, Beebe shot entire sequences on 35mm, but that was not the case on Miami Vice. Instead, the decision to use film was made on a shot-by-shot basis. “We made a commitment to shoot HD, and we really only turned to film in situations where we absolutely could not use HD,” says the cinematographer.

The look of Miami Vice is distinguished by very hard, bare sources and high contrast. “In a broad sense, it was a show about single-source lightning,” says Beebe. “I looked for opportunities where I could light with a single broad side-light to create a deep shadow on the faces. That’s often a challenge when you have a very dynamic coverage and actors who are constantly moving and turning into shadows; turning into full, flat front light; or becoming completely backlit! I often had to adjust my single-source approach according to the requirements of the scene. In general, I found myself leaning toward much harder sources all around to get that great half-light effect.”

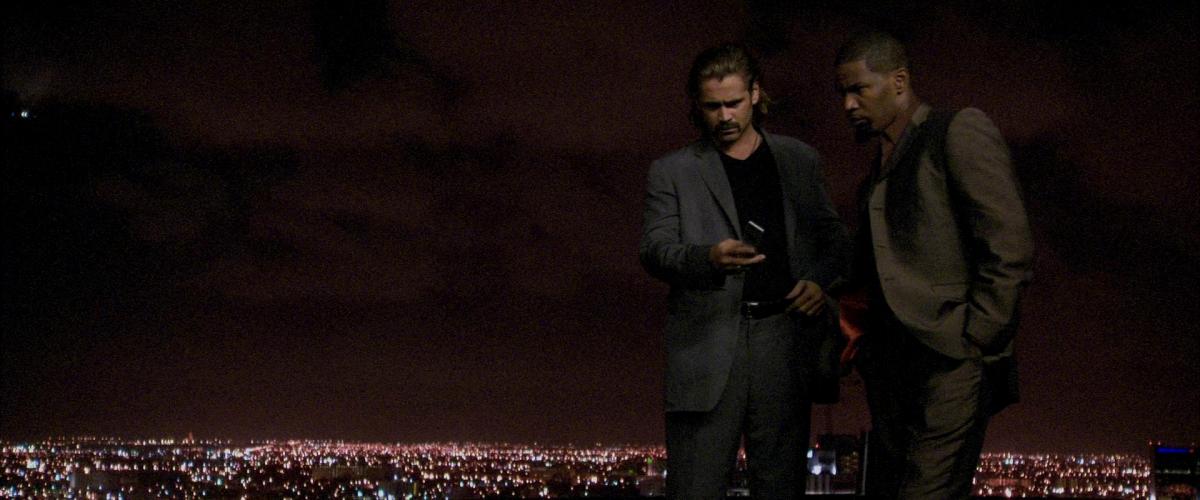

These sources were often undiffused 20K tungsten Fresnels. One large-scale sequence takes place at a boatyard in Miami and involves a major shootout between Crockett (Colin Farrell) and Tubbs (Jamie Foxx) and the bad guys. Beebe wanted the whole sequence to have the single-source sidelight look, so the crew lined up five 20K Fresnels on one side of the boatyard. “The real challenge was making the multiple sources look like a single source,” he says. “We had to do a lot of flagging between the fixtures to blend the light output and eliminate multiple shadows. It was very tricky to get uniform coverage and not overlap the lights. Scott Robinson, our key grip, and his guys had to work hard setting flags and then re-establishing the effect night after night for a week.”

The sequence is complicated by a hostage exchange that takes place in the boatyard’s large, open field. Isabella (Li Gong), the mistress of one of the villains, is exchanged for one of Crockett and Tubbs’ colleagues, Switek (Domenick Lombardozzi). The coverage for the scene starts out with A-camera operator Jay following Lombardozzi across the field handheld, with Gong walking toward camera in the background. As the two meet in the middle of the open field, Jay spins around 180 degrees to follow Gong’s continued walk back toward Crockett. Because the spin happens in the middle of the field, Jay’s camera kept throwing a shadow on the actors. The solution was to time out the walk and the switch so the exchange would take place within a narrow channel of complete shadow in the middle of the field where Jay could do his rotation.

In an earlier sequence, Crockett and Tubbs travel to the Dominican Republic to meet with Montoya (Luis Tosar), the lead villain, in an abandoned town square. After scouting locations in Dominican Republic, the production picked a rundown area called The Mercado Nuevo. The production obtained permission to film for a few days but was unable to gain control over the city’s electricity, which was often shut down at night. Beebe, Robinson, gaffer Steve Mathis, rigging gaffer Mark Wostack and rigging grip Don Reynolds subsequently conducted an extended scout to determine how to light up the entire square with their own fixtures could help light up an area that was about the size of a football field,” recalls Beebe. “It took a fair amount of planning to economize the power runs in that huge square, ant to light up nearly every inch with our own fixtures.”

For key lights in the sequence, Beebe placed three Nine-light Maxi-Brutes on the rooftops and a fourth in “one of only two scissor lifts found in the Dominican Republic,” he says. “I think we only used one or two bulbs in each of the unites due to the fact that we were working a such low levels on the cameras. What was important for Michael was that you feel our heroes’ vulnerability as they walk across the no-man’s land. They sport a sniper position on the rooftop and realize they’re in trouble. It was important to see the openness of the location and the distance they had to move through without protection.”

When working with HD, Beebe doesn’t use a traditional light meter. “A handheld waveform monitor becomes my meter,” he says. “Particularly when we were working run and gun, I’d cable into the back of the camera with a handheld waveform and check my percentages. If the cameras were cabled back to, the mothership, I could check there quite easily.”

“Building on our experiences on Collateral, we set some pretty strict guidelines as to how I would expose, especially faces and what percentages were acceptable to avoid digital noise,” he continues. “On night exteriors, I tried to keep the exposure values at around 30 or 40 percent, never letting them fall below 20 percent, and kept gain at +3dB most of the time, rarely going to +6dB. It’s tricky, because you can look at the monitor and think the exposure looks great, and when you check the exposure values on the waveform, you find it’s too low. When it’s too low, you get noise, and often you can’t see the noise on the monitors. The only way to know for sure is to check the image on a large screen.”

To facilitate that, the production set up a screening room with an NEC DLP IS8 2K projector. Dailies were view on HDCam in the United States and on HDCam SR clones outside of the country. (When the production was working in another country, dupe clones were made before tapes were sent to the States.) An LUT box was hooked to the projector so Beebe could dial in a final print emulation when necessary. “Seeing your dailies on a big screen is crucial,” he remarks. “As much as you balance out the set monitors and test your way through the process, there are things – particularly electronic noise – that somehow get lost on those cathode tube monitors. It’ll look great on the set, but when you blow it up on a big screen, there’s noise everywhere. Sometimes when you’re trying to shoot fast in a low-light situation, you can look at the monitor and think the image is fine, but when you see it on the big screen later you find you shouldn’t have gone as far as you did. So our dailies projection was important, and keeping disciplined with the exposure values was really key.”

“There was much debate about where HD sits relative to film and what the future of film is, but I feel HD is merely another tool for the filmmaker,” he concludes. “It’s a system that will just continue to improve, and who knows what these cameras will be capable of in five years? Ultimately, it’s a tool for realizing the story, just as film cameras are. At the end of the day, my choice of a system is based on what best serves the telling of that particularly story.”

Technical Specs Miami Vice

2.37:1, High-Definition Video and 35mm

HD: GrassValley Thomson Viper; Sony CineAlta HDK-T950; CineAlta HDW-F900; Zeiss DigiPrimes, DigiZoom

35mm: Arri 235, 435; Zeiss Ultra Primes; P+S Technik T-Rex SuperScope

Kodak Vision2 Expression 500T 5229, 50D 5201

Digital Intermediate

- 1Bryant Frazer, “How DP Dion Beebe adapted to HD for Michael Mann’s Collateral,” StudioDaily, 1 August 2004.

- 2Jean-Baptiste Thoret, Michael Mann: Mirages du contemporain (Flammarion: Paris, 2021).

This text was originally published in American Cinematographer, August 2006. Article reprinted with permission from American Cinematographer magazine.

Thanks to Jay Holben, Stephen Pizzello and American Cinematographer