The Image

The Image by the French surrealist writer Pierre Reverdy originally appeared in Nord-Sud, the literary magazine he founded in 1917 with Guillaume Apollinaire and Max Jacob. The text, quoted and recut, shows up like a refrain without reference in several of Jean-Luc Godard’s films. The crux of Reverdy’s piece, which also goes for Godard’s work, is that the image, as a monolithical entity that can be isolated, doesn’t exist. “I’ve always said”, Godard said at the press conference on the occasion of the premiere of Passion at the Cannes Film Festival, “that images don’t exist in cinema. There is always an image before and an image after. In cinema, the present doesn’t exist. Monday doesn’t exist. It’s always either Sunday or Tuesday. And Monday is simply the link between the two. And that’s the image. And even the image doesn’t exist. There is a text by Pierre Reverdy that goes: “An image is not strong because it is brutal or fantastic – but because the association of ideas is distant and fitting.” Everything is always interval [entre-deux]. The light is always between day and night, between light and night. Everything is interval.”1 Reverdy primarily talks of metaphors, metonymies and analogies, a poetic interval that is the result of two “more or less distant realities”. In Godard, this also becomes a literal technique: a definition of editing, the work of two images combined, in which the relationship between the two images is characterized by difference and resemblance.2 This way, the image becomes a relationship, a connection, an association. Godard will also connect this to an idea of historiography through images. “When I think about something, I’m actually thinking about something else,” says Edgar, the protagonist of Éloge de l’amour, several times throughout the film. A view which, according to Ewa Mazierska, summarizes Godard’s idea of history as editing, a historiography in which events and ideas at a distance from each other are connected and produce new meanings that were unavailable for those who lived the events.3 For Godard, editing remains a virgin territory in film history and practising his idea of editing “la vraie mission du cinéma” at that.4

Gerard-Jan Claes

*

The Image

The image is a pure creation of the mind.

It cannot be born of a comparison, but only of the bringing together of two more or less distant realities.

The more the relations of the two realities brought together are distant and fitting, the stronger the image – the more emotive power and poetic reality it will have.

Two realities without any relation cannot be usefully brought together. Then there is no creation of an image.

Two contrary realities will not come together. They are opposed.

We rarely get anything strong from such an opposition.

An image is not strong because it is brutal or fantastic – but because the association of ideas is distant and fitting.

The result obtained immediately controls the fittingness of the association.

Analogy is a means of creation – a resemblance of relations; and the strength or weakness of the image created depends upon the nature of these relations.

What is great is not the image itself – but the emotion it provokes; if this emotion is great, we value the image proportionally.

Emotion thus provoked is pure, poetically, because it is born beyond all imitation, all evocation, all comparison.

There is surprise and delight in finding oneself before a new thing.

We cannot create an image by comparing (always weakly) two disproportionate realities.

On the contrary, we create a strong image, one that is new for the mind, by relating, without comparison, two distant realities whose relations can be grasped by the mind alone.

The mind must grasp and taste a created image without any admixture.

The creation of the image is thus a powerful poetic means, and we should not be astonished by the major role it plays in a poetry of creation.

To remain pure, this poetry requires that all means come together to create a poetic reality.

There cannot be any direct means of observation interfering; they only serve to destroy the whole by blowing it up. Such means have another source and another goal.

Means of different aesthetics cannot strive together toward the same work.

Only a purity of means commands the purity of works.

The purity of the aesthetic derives from that.

Pierre Reverdy

*

An image is not strong because it is brutal or fantastic – but because the solidarity of ideas is distant and fitting.5

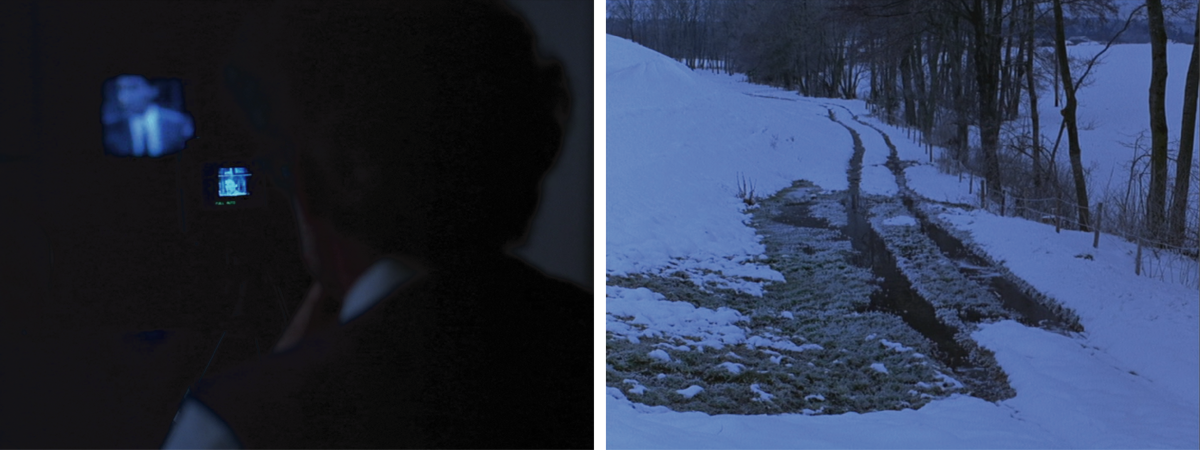

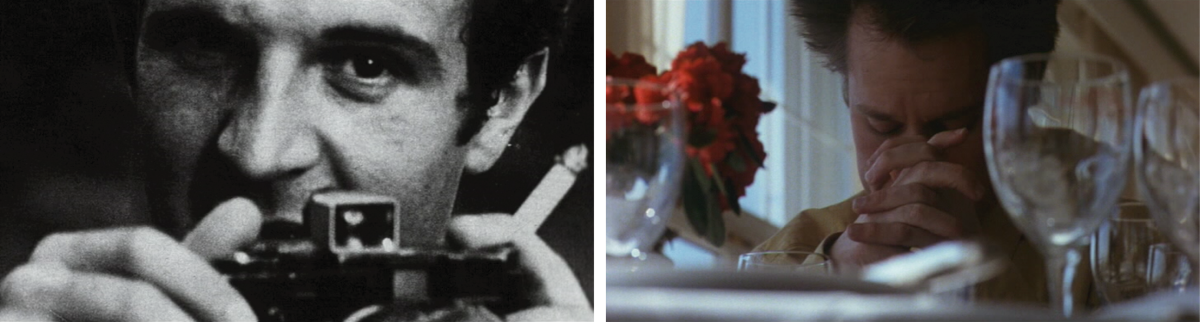

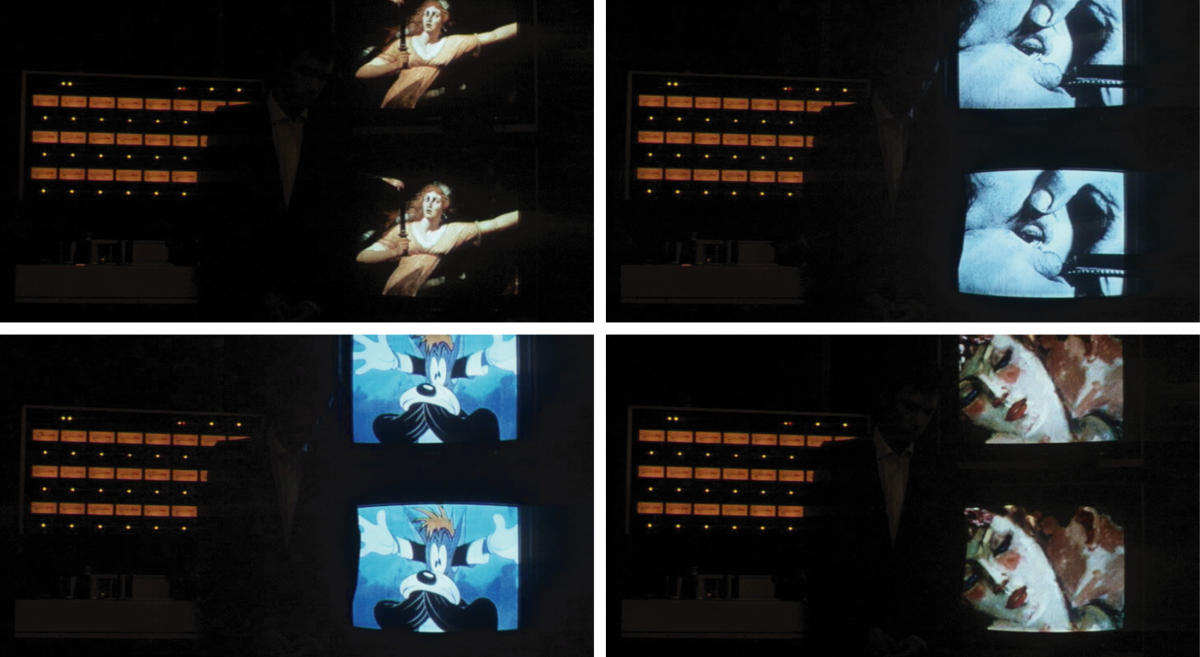

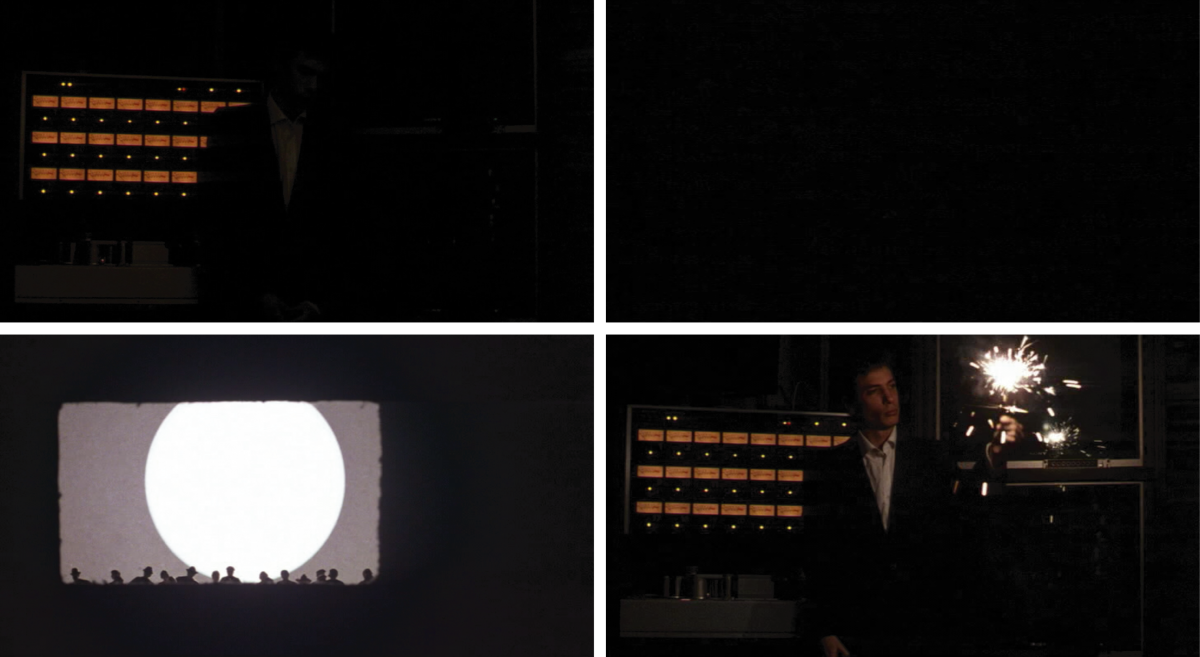

Passion (1982)

All is one and one is in the other and those are the three persons.6

Hélas pour moi (1993)

The image is a pure creation of the mind.

It cannot be born of a comparison, but only of the bringing together of two more or less distant realities.

The more the relations of the two realities brought together are distant and fitting, the stronger the image.

An image is not strong because it is brutal or fantastic but because the association of ideas is distant.

Distant and fitting.

JLG/JLG - autoportrait de décembre (1994)

If an image, looked at separately, expresses something clearly, if it includes an interpretation, it will not transform itself in contact with other images.

The other images will have no power over it, and it will not have power over other images. No action, no reaction.7

And you, my dear Mr. Shakespeare. You see, all those reckless words for the simple things on earth. It’s only life and how it works.

And you, my dear Mr. Shakespeare. You see, all those reckless words for the simple things on earth. It’s only life and how it works.

Thank you indeed for this definition of life.

Oh, not life. Only an image.

Oh, not life. Only an image.

An image? What’s that again?

The image is a pure creation of the soul.

It cannot be born of a comparison, but of a reconciliation of two realities that tell more as far apart.

The more the connection between these two realities are distanced, the stronger they get to be, the more they could have emotive power.

Two realities, that have no connection, cannot be drawn together usefully.

There is no creation of an image.

Two contrary realities will not come together. They oppose each other.

One rarely obtains forces and power from either position.

So out went the candle, and we were left darkling.8

So out went the candle, and we were left darkling.

An image is not strong because it is brutal or fantastic but because the association of ideas is distant and true.

The result that is obtained immediately controls the truth of the association.

Analogy is a medium of creation. It is a resemblance of connections.

The power or virtue of the created image depends on the nature of these connections.

What is great is not the image, but the emotion it provokes.

If the latter is great, one esteems the image at its measure.

The emotion thus provoked is true because it is born outside of all imitation. All evocation. And all resemblance.

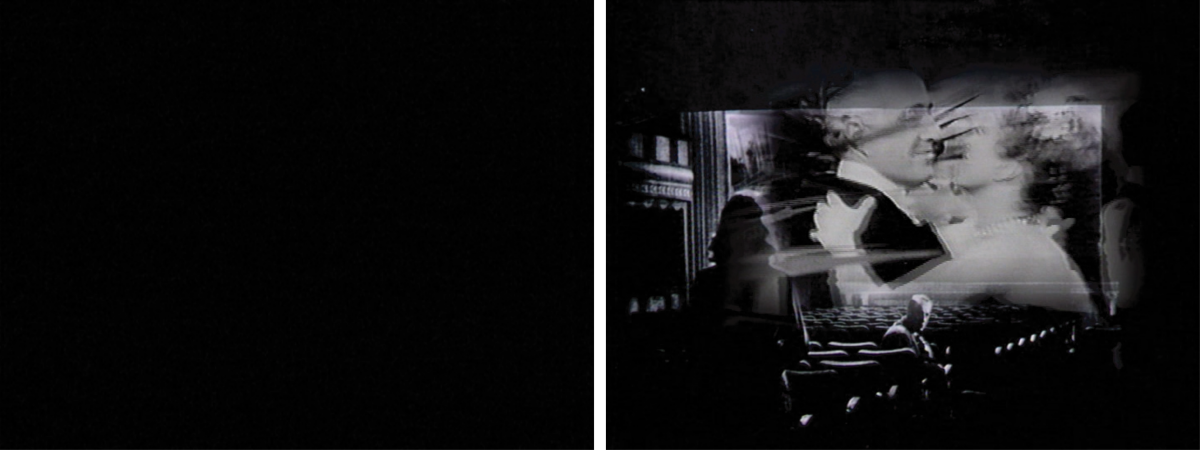

King Lear (1987)

When I think about something, I’m actually thinking about something else.

We can only think about something when we think about something else.

You see a new landscape, for example, but it’s only new because you compare it in your mind to a different, older landcape, one you already know.

Éloge de l’amour (2001)

The image is not strong because it is brutal or fantastic

but because the association of ideas is distant.

Distant and fitting.

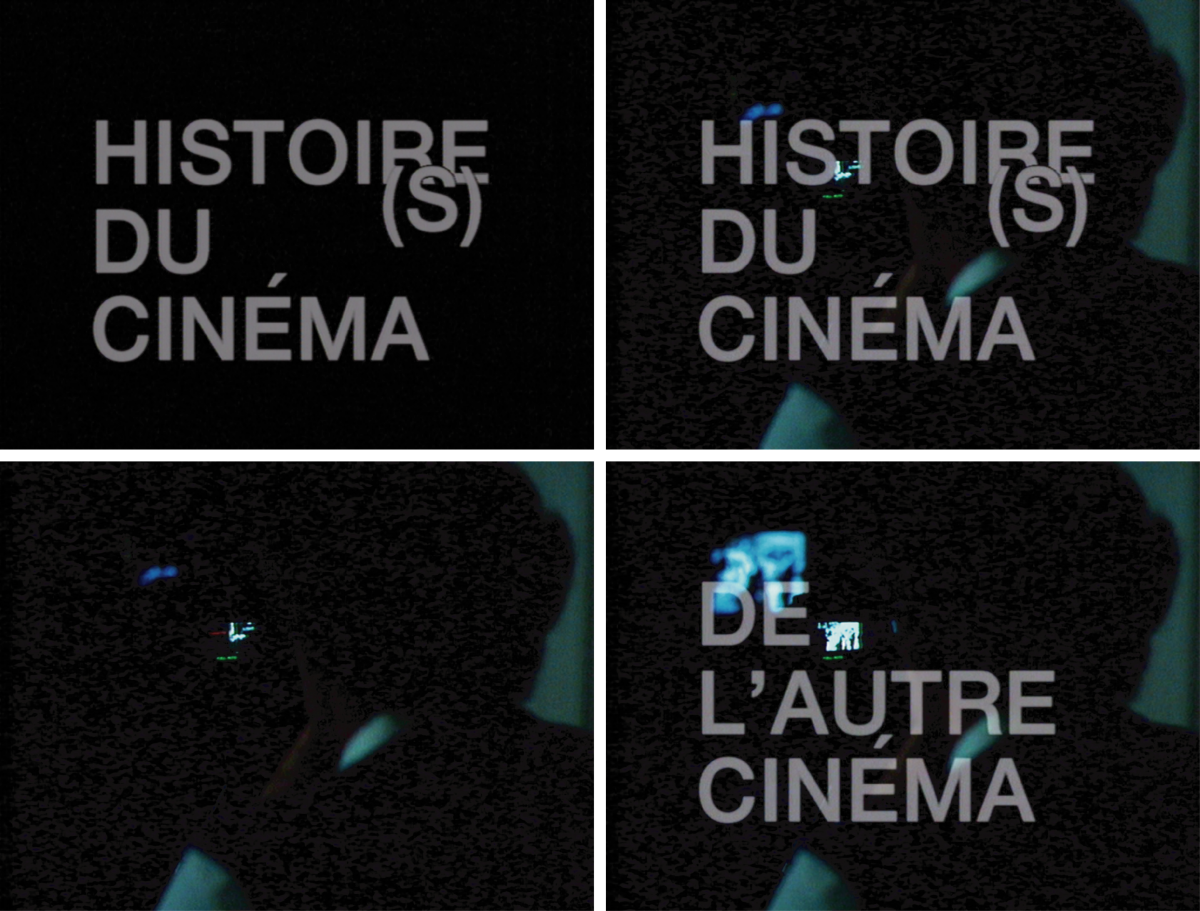

Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998)

- 1Le cinéma des cinéastes - Conférence de presse de Jean-Luc Godard au Festival de Cannes 1982, France Culture, 1982.

- 2Volker Pantenburg, Farocki/Godard: Film as Theory (Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, 2015).

- 3Ewa Mazierska, European Cinema and Intertextuality. History, Memory and Politics (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan: 2011).

- 4Gavin Smith, “Interview: Jean-Luc Godard,” Film Comment, March/April 1996 Issue.

- 5“Une image n’est pas forte parce qu’elle est brutale ou fantastique mais parce que la solidarité des idées est lointaine et juste.”

- 6Léon Brunschvicg cited in Hélas pour moi (Jean-Luc Godard, 1993).

- 7Robert Bresson, Notes sur le cinématographe (Paris: Gallimard: 1975).

- 8“So out went the candle, and we were left darkling.” William Shakespeare, King Lear. Translation: Willy Courteaux.

First published in Reverdy’s magazine Nord-Sud, no. 13 (March 1918); partial translation from the French by Mary Ann Caws completed and revised by Adrian Martin. The somewhat free translation recited by Jean-Luc Godard in his film King Lear (1987) has also been consulted; thanks to Michael Witt for transcribing it in his book Jean-Luc Godard, Cinema Historian (Indiana University Press, 2013).

© Estate of Pierre Reverdy

Images from Passion (1982), Hélas pour moi (1993), JLG/JLG - autoportrait de décembre (1994), King Lear (1987), Éloge de l’amour (2001) and Histoire(s) du cinema (1988-1998)