A Place in Time and Killer of Sheep: Two Radical Definitions of Adventure Minus Women

It would be more than fair to say that in American films, the motif of adventure is one of the favorite story-telling devices. So many films come to mind – from the most banal to the most memorable of the western, detective, and war genre films of the 30’s, 40’s and 50’s to the rash of modern-day science fiction films patterned on the Star Wars or Close Encounters formulas. From Bogart to Cagney, Marian Brando to James Caan, adventure is the name of the game: war, murder, treasure hunts, safaris, journeys to outer space and fast cars, filmic adventure is a familiar odyssey with familiar rituals and rites of passage. The word adventure itself has heroic overtones; it implies a journey in which the risks count as heavily as the potential gains. It presupposes a rupture with present definitions and present surroundings in favor of the unknown. It is also implicitly masculine: men have adventures, women may support, encourage, even inspire them, but the adventure itself is a potent expression of maleness.

Certainly, the Black film wave of the 70’s patterned itself on an adventurous mythology. Superfly, Shaft, etc., reflected an on-going fascination with the male as adventurer/conqueror/hero. Nor did Sidney Poitier break ground with this tradition either as a film hero himself or as a director with his "Uptown comedy-adventure films, in which Poitier/Cosby fall, stumble or scheme their way through a series of misadventures while their wives provide stand-up relief to their antics.

The question arises then: What happens in the Black film tradition when we turn to speak of the representation of Black women in independent Black Cinema approached from male viewpoints. Two important films come to mind: Larry Clark‘s Passing Through, in which a man seeks to come to terms with his past, and Bill Gunn’s Ganja and Hess, in which the hero is in search of his own salvation. Both films fit the adventurous mold but the adventure has taken an interior turn. Still, they are particularly male odysseys laden with potent male imagery.

Two other films stand out in my mind that take the adventure story theme to another level, and therefore deserve a closer look: Charles Lane’s A Place in Time, and Charles Burnett’s Killer Of Sheep. A Place in Time carves out a very slippery terrain. If the young hero’s odyssey can be called adventure, it is one in which the search is so amorphous, so preoccupied with the fragile possibility of love and kindness in a chaotic world, that to label it too strictly becomes difficult. One might preferably call it a moral tale, with its strange indebtedness to the American silent-era comedy. For when you watch it, Chaplin or Keaton come to mind, but with a new, surprising overtone. It is acceptable for Chaplin to waddle down the street, fall in and out of scrapes, be made the butt of ethers’ cruelty and insensitivity for Chaplin is white, and the jokes played on him, while funny, are not intended to represent the dominating biases of society against the character and sensibilities of a particular group.

Despite the fact that Lane chose to tackle sensitive ground, that the hero of A Place in Time (with all his Chaplinesque charm) happens to be black is so radical a step in a new direction, that when I first saw it, it took my breath away. With his round, expressive face, poignant drooping eyes, Charles Lane’s hero – played by Lane himself, is without a doubt a bit of a bungler and a fool. He tries to make a living as a street artist, but in the midst of his sketching he is forever falling off his stool. His belongings are always in danger of being ripped off. When he intervenes in other people’s fights, or muggings, he winds up taking the blame or being beaten up in their stead. And when he falls in love, he does so in the most heartbreaking, doe-eyed way imaginable and thus remains vulnerable to the slightest hurt. In the end, when after many misadventures he returns almost unwillingly to his craft, he reads in the face of a woman who asks to be sketched, his own love and caring for beauty; he acknowledges her with a look that despair will not win out.

In the annals of filmmaking by, about or incidentally peopled with blacks, there does not seem to exist a hero quite like Lane’s. With all the terrible mythology around Black people as true bunglers and tools, Lane has created a black hero with true pathos – avoiding all the pathetic traps into which the Steppin Fetchits of the world have fallen. It is an act of great jubilation that Lane has replaced the bulging eye-balls of the frightened negro with the soft humane consciousness of a being whose adventure is life itself. The quest for the meaning of life is as much the black man’s inner quest, foolish, bungling and wise, as it is that of any other human soul.

Still, with all its radical import, the film refuses to extend beyond the masculine boundaries so carefully laid out as adventurous terrain. The two women in the film – the hero’s girlfriend and the woman who closes the film with her gentle, aging face pleading to be sketched, are much more symbolic characters than real ones. When I recall the film visually, I see the girlfriend as a puppet through which the hero pulls certain vital strings. She is one of the things that happen during the course of the film as is the woman at the end whose face allows him to resolve some notion about existence that he has been working out since the beginning of the film. In an otherwise radical movie, the women are once again reduced to still-lives, background tapestry for a complex male dance.

In Killer Of Sheep, Charles Burnett also proposes radical notions of adventure: a man in the process of going about his daily existence must confront his own willingness to live or die. The adventure of the spirit, Burnett seems to say, hap pens in the pursuit of life – of one’s daily bread, on the terms and within the peculiar limitations imposed on that particular life.

Simply recounted, in Killer Of Sheep, we meet a man who works in a stockyard killing, stripping and shearing sheep for a living. He has a family, friends, a small house in need of much repair. When we meet him, we are quickly made aware of his depression. Nothing seems worthwhile. He scorns his wife’s efforts to love and comfort him, his children’s attempts to make him laugh. There is a kind of futility surrounding him that deadens him to the world. Slowly, he begins to teel more in harmony with life. Vet this very harmony seems to emerge out of failed moments: a newly bought engine needed to repair his truck ruined in a careless accident, a family outing deadened by a flat tire; the humor of both these situations is not lost on him, He knows that things are unlikely to get much better, yet by the end of the film, he turns a gentle ironic face towards life. He has decided to stay in the game.

In no other black film that I have seen has working-class black life been captured with such completeness. There is no apology for its rough edges. No sociological explanations border the fringes. It is alive and well in Burnett’s gentle lens, and it is what it is. Even more than this is the film’s daring willingness to be particular. While it is surely possible to view the film as a metaphor for the plight of the black man in general, Burnett seems to go to great pains to make his hero one man rather than all men. The film seems to say again and again this is one particular black man you are watching, and he is coming to terms with his life. His acceptance of his own existence is an individual thing that now separates him from any other man, black or white, who has so far refused this private dialogue with himself.

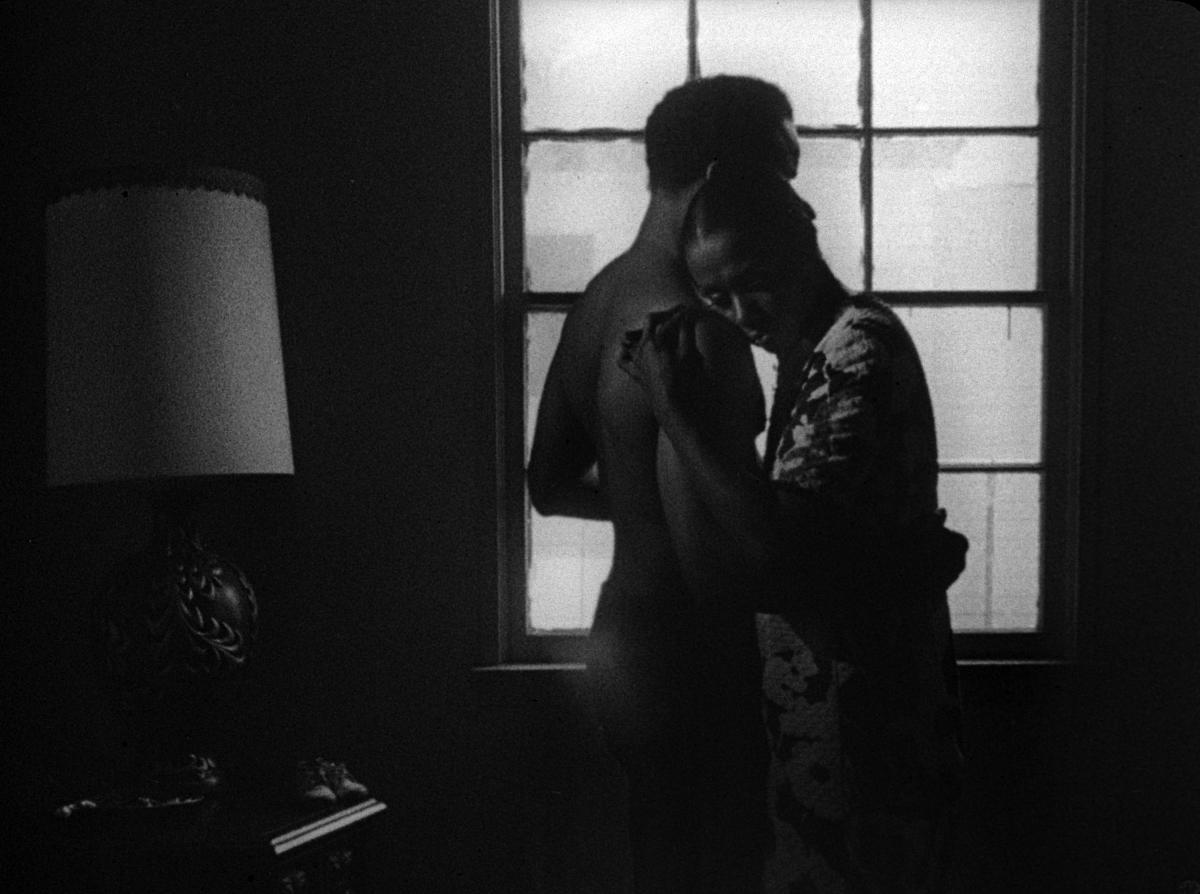

Once again, a film so radical in its perspective suffers from a kind of stagnant female impotence that is made poignantly clear. With Dinah Washington crooning “This Bitter Earth” on the stereo, the hero and his wife dance a slow, powerful dance in which she tries to coax him out of despair with her own real needs for intimacy and communication, only to be rebuffed by the deep inertia still gripping him. Even the composition of the shot speaks volumes: unable to coax him into union, she walks out of the frame, leaving him there alone. And one cannot help but impose on that shot the notion of female helplessness in the face of the enormity of male anguish. That notion is reinforced by the film’s final scene, when we sense Burnett’s hero emerging from despair and reaching out once again to his wife for companionship. This reaching out must be faced for what it is: a private male decision imposed upon her in much the same way that his earlier withdrawal has imposed on her. She is not a participant in any true sense of the word.

How odd that two films which propose a new kind of freedom within the Black experience never quite extend this freedom to (their) women. It is certainly to Lane’s credit that he abolishes Steppin Fetchit before our eyes, yet allows for the genuine foolishness of man. Likewise, the boldness with which Burnett pursues the issue of choice is not to be taken lightly, for he flatly refuses the notion that Black life is so confining an exercise that choice is irrelevant. Choice is the very essence of life, he proposes, and a man only achieves his manhood by taking upon himself both the joy and the despair of his lot. In American film terms, the notion of adventure has certainly undergone a Black metamorphosis. Yet how sad that in the end, we are still left with stagnant female souls hovering aimlessly around the male universe. How limiting is the idea that only men despair; women can only comfort.

This text was published in Pearl Bowser and Ada Griffin eds., Color: 60 Years of Images of Minority Women in Film, 1921-1981 (New York: Third World Newsreel, 1984).

With thanks to Nina Lorez Collins and Third World Newsreel.

Image (1) from A Place in Time (Charles Lane, 1977)

Image (2) from Killer of Sheep (Charles Burnett, 1978)

This text was published on the occasion of ‘Milestones: Losing Ground’, a collaboration between Courtisane and Sabzian. On the occasion of the online screening, several texts have been published on Sabzian, selected and edited by Stoffel Debuysere and Gerard-Jan Claes. ‘Milestones: Losing Ground’ takes place on Thursday 3 June 2021 at 19:30 on Sabzian. You can find more information on the event here.