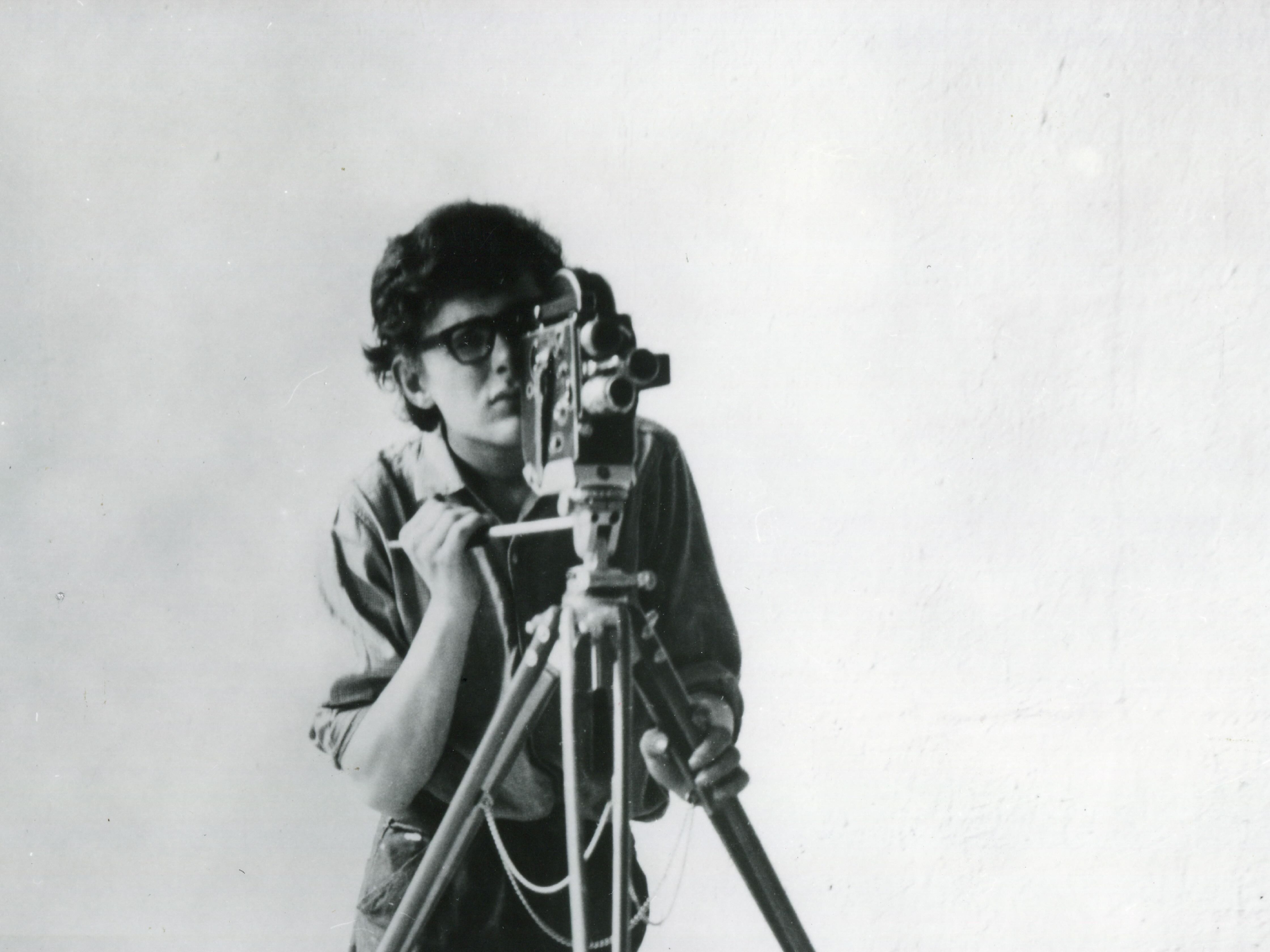

Frans van de Staak

People Passing Through Me in an Endless Procession

An artist and engraver, Frans van de Staak (1943–2001) first encountered the power of cinema in a sequence from Michelangelo Antonioni’s Red Desert. He went on to enrol in film school and founded CINEECRI, a journal he distributed himself. Using grant money earned through graphic design, he made a series of short films in the 1970s that laid the groundwork for his cinema: early attempts to transpose texts by writers such as Korneliszoon Poot and Spinoza to the screen. Rather than striving for faithful reproduction, he filmed amateur actors in their effort to give voice to the text, judging takes more by ear than by eye.

At the end of the decade, he began collaborating with filmmaker and partner Heddy Honigmann, who edited four of his films, including his first feature, De onvoltooide tulp (1980). Later, working later with poet Lidy van Marissing, he explored the everyday use of language, idioms, and the interplay between poetry and film editing. He played a formative role for a new generation of emerging filmmakers and forged close relationships with leading figures of Dutch experimental cinema, including Johan van der Keuken. In his self-built workshop, which ensured complete autonomy, he edited sound and image, recorded voices, and welcomed beginners, sometimes producing their films. Collaborations with poet Gerrit Kouwenaar sharpened his attention to gesture and the sensory, while music by Bernard Hunnekink and recurring shots of objects and elements of nature gave his cinema a concrete yet meditative quality. In the 1990s, having further mastered his craft, he began working with professional actors, though his films remained largely confined to the Rotterdam Film Festival, where Huub Bals was an ardent supporter.

Returning to short forms before his final film Lastpak, van de Staak affirmed his desire to make things tangible when life’s temporality escapes us. Jean-Marie Straub called him the only worthy heir of Dziga Vertov: van de Staak sought to make the world better by inviting viewers to observe it rather than by telling stories. Asked by Van der Keuken what propelled his work, he spoke, “Desire, I’m driven by desire, not by anger, yet a very strong emotion indeed. This desire arises from the tension between being alone and being together in society.”1 2