A fearless Antigone, refusing to allow the dishonored body of her murdered brother Polynices to be devoured by vultures and dogs, defies the Thebian tyrant Creon by burying him.

EN

“Of all Straub-Huillet films, I remember Antigone as the one most at peace with itself, in all its details. Or rather: in all the instances we pay attention to its so-called details. In all its well-ordered structure and, at the same time, incoherence. Because, despite the film’s obvious overall monolithic quality, while we are trying to follow its words – and usually fail due to its powerfully lyrical Hölderlinesque language – we keep paying attention to detail. The strangely billowing garments, the oily quiver of the olive leaves in the wind and the idiosyncratic chant-like intonation. And its eccentric rhythmic phrasing, which suggests that the language we are hearing, that what is being said and, even more so, what is not being said, is being made up there and then.”

Klaus Wyborny1

“Antigone incorporates in many ways the return to mythic origins suggested by films such as Moses and Aaron or From the Cloud to the Resistance. It returns to the aesthetic origins of contemporary film and theater in its use of the visual simplicity of the silent cinema and the staging of Sophocles’ play in a Greek theater of his era. It also returns to the mythic origins of civil society in the death of the heroic individual: Antigone’s voluntary self-sacrifice parallels Moses’ sojourn in the desert and Empedocles’ plunge into volcanic fire. And its visual images, like its language, straining to be both German and Greek, mark the border between Europe and the other continents: the “African sun” shines on Sicily, as Huillet has put it.

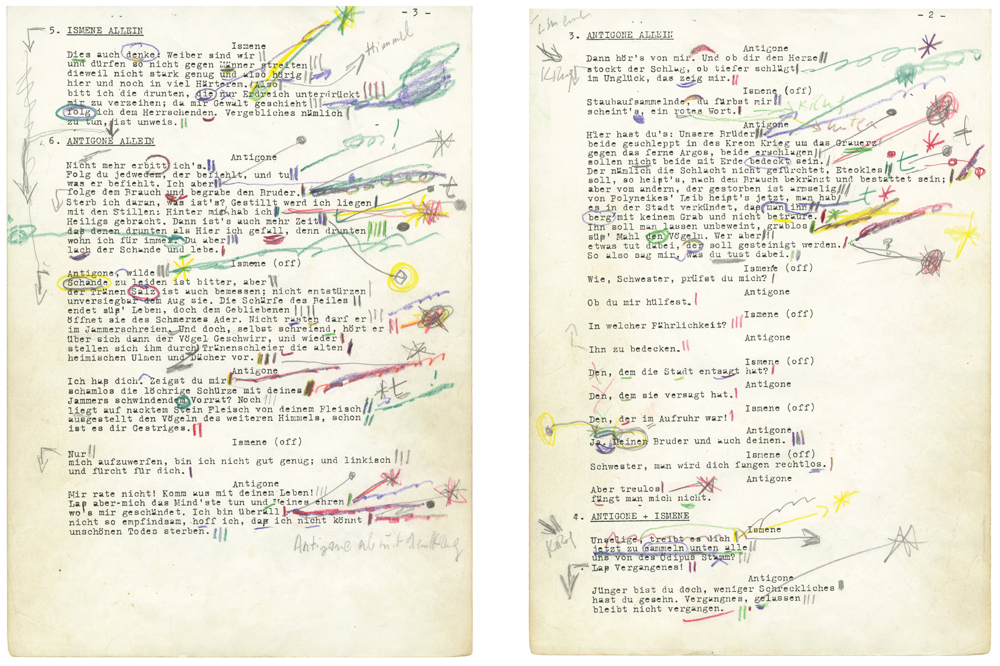

Danièle Huillet’s love for the light and landscape of Sicily, the fascination with the Teatro de Segesta (a Greek theater in Sicily dating from the fourth century B.C.E. and one of the best-preserved Greek theaters of antiquity, discovered by Straub/Huillet some twenty years earlier while scouting locations for Moses and Aaron) led her and Straub to conclude their ten-year consideration of Hölderlin while returning to Brecht’s political aesthetics. Brecht’s version of the Hölderlin Antigone translation is rather obscure among his works and seldom performed, but Straub has emphasized that the text is “very much Brecht,” including some of the strongest writing he ever did for the theater.”

Barton byg2

“Objects in Time: The Tree and the Autostrada

The full title alone reveals that this is a film about time. And there has never been a time to be unconcerned with state power, human love and honor, and the devastation of war.

Much of the film is from the past: the stones from Sophocles' time, the words from the times of Hölderlin and Brecht. But the voices, the bodies, the light, the air, and especially the tree are from the now of the film.

And how does the film take us into the future? Creon's defeat is ominously contradicted by the expanse behind him, a 20* Century empire revealing the viaduct of the Autostrada A29 leading toward the sea. Straub hated the idea of film imitating painting, but I can't help but see Cézanne here – as in so many Straub/Huillet portraits of figures, rocks, earth, and trees.

Brecht's words of warning onscreen at the film's end remain prescient, with the Carabinieri's helicopter thundering in our ears. War has been uninterrupted since this film was made.

But there is also the tree, Antigone's tree, the tree that "was also Antigone," as Huillet put it. A humble nettle tree stands by as witness to the comings and goings and protestations of Haemon, Ismene, Tiresias, and Antigone. Danièle Huillet had worried that the tree would not survive the 1980s, and without the tree, they would not have made the film. Since the film was made, a number of those involved have died, including Albert Heterle, Louis Hochet, William Lubtchansky, Danièle Huillet, and Jean-Marie Straub. Like the Autostrada, Google Street View is part of the violent technology that links the film to our own future. But using Street View I can also see that today the nettle tree is flourishing.”

Barton Byg3

- 1Klaus Wyborny, www.viennale.at.

- 2Barton Byg, Landscapes of Resistance, 1995, 215.

- 3Barton Byg, "The Antigone of Sophocles after Hölderlin’s Translation Adapted for the Stage by Brecht 1948", Balthazar, 2023.