Two Eyes in the Night

Pedro Costa’s Vitalina Varela

There are several ways to talk about Vitalina Varela. The first would start from its overall narrative structure. Classic, even Hollywoodian: it starts with men returning from a funeral. Then, the plane bringing the woman who loved the deceased. She is going to meet witnesses of his life, search his home, and discover his secrets. Little by little, the puzzle of their two lives, of what united and separated them, is thus reconstructed. And the journey back in time ends in the evocation of the young happy couple, building this house where they have never lived together but where the image will unite them forever. An unhappy and yet indestructible love story.

This way of storytelling has at least one merit: it underlines the evolution that seems to lead Pedro Costa’s cinema back to an overt fictional structure. This movement of return reverses the direction the filmmaker had taken in Ossos, in which the narrative form seemed to come undone, as if the lives of the immigrants and dropouts discovered in the alleys of Fontainhas made it impracticable. The film ended with a door closing, as if to definitively refuse the spectator the traditional lament of the poor. So, one could consider the entire cycle that begins with In Vanda’s Room as one long effort to invent a new form capable of rendering the lives lost in the slums of the Lisbon suburbs or in other shanty towns of European metropolises. In Vanda’s Room adopted a quasi-documentary form in which the film’s temporality seemed to be modelled after the frozen time of the drug rituals that were pushed away from the outside by the rapid progress of bulldozers destroying the shanty town. Colossal Youth shattered this overly linear form by enclosing the continuation of Vanda’s story and prosaic conversations in a mosaic of small scenes ranging from Brechtian dialectical lessons (the visit to the Gulbenkian Foundation) to Benjaminian allegories (the dialogue between Ventura and Lento in the burned-out house). Horse Money extended this second vein by condensing forty years of migrant life into the unity of an immobile time and the geographical unity of a hospital – real and symbolic – opening directly onto the underworld. While the space in which Vitalina Varela is set remains, at least symbolically, a place between life and death, the film seems to open up this immobile time by adopting the fictional form of an inquiry into a deceased person. Other characteristics highlight this shift. The dialogue that Vitalina establishes with the dead man is immediately perceived as a fictional scene. And Ventura, who had only played himself in previous films, now appears as a full-blown actor, playing against type a double role taken from the world of fiction: a fallen priest character distantly echoing Bernanos’s and Bresson’s miserable country priest; but also a privileged witness of the life of the deceased, a witness behind whom one sometimes seems to perceive the wandering shadow of Joseph Cotten/Leland in his retirement home, even though Citizen Kane is not part of Pedro Costa’s pantheon.

But that’s where the formal similarity ends. There will be no flashbacks. No sentimental child; no feverishly ambitious adult will rise to re-embody the deceased. No fabulous mansion where a simple child’s dream would hide. The emigrant’s dream had long since waned, buried in one of the shanty towns hastily erected with salvaged materials by these construction workers waiting for a future that would never come. It is impossible to bring the distinct bodies of a story back to life in flashbacks, to endow them with the colour of life. They have become shadows that slide into the night, all alike. And in this night the inquiry into the deceased will take place. In the first shot we can only barely discern crosses dominating high walls along which silhouettes parade with no more than the sound of a crutch resonating on the pavement. We will understand that they are friends of the deceased returning from the funeral when we see two of these shadows briefly take shape while cleaning his flat. It is still night when we later see Vitalina’s silhouette appear framed by the door of the airplane before her bare feet come down the steps and a group of other shadows, dressed in cleaning-crew colours, appear on the tarmac and greet Vitalina in a low voice, telling her that her husband has already been buried and that there is nothing for her to do here: there is nothing for her in this abode of shadows. And only at the very end of the film sunlight will appear, to illuminate the cemetery where the deceased is resting. The entire inquiry into the deceased will take place during the night, or rather in a universe where day and night, inside and outside are indistinguishable, where bodies pass each other in the half-light, a mother calls in vain the son she is bringing a meal to, idle men play cards, visitors knock on the door, without any of these workers ever leaving for or returning from work.

One could think, then, that the fictional structure of the inquiry into the deceased is only an appearance, belied by the frozen time of this abode of shadows: a time occupied by a long funeral ceremony arranged by Vitalina to replace the funeral that she was deprived of. Slowly, watching herself in a mirror, she takes off her black scarf and ties a white scarf round her head, which she will later untie to wrap a crucifix on a makeshift altar with two candles burning in glasses in front of photos of the deceased. Men – or rather indistinct shadows – file past her, paying tribute to the image, murmuring words of condolence. She offers a ritual meal, an opportunity for the shadows to become distinguishable, to evoke moments spent with the deceased and talk about his last days. Later, Vitalina will have a mass said in his memory, at which she will be the sole attendant. And the ending of the film sees her peacefully reburying, as it were, in the cemetery’s full daylight, the one who had died without waiting for her. So, the film should be regarded as the unfolding of a long lament that not only mourns Joaquim’s death but his very life, a life buried in this underground universe.

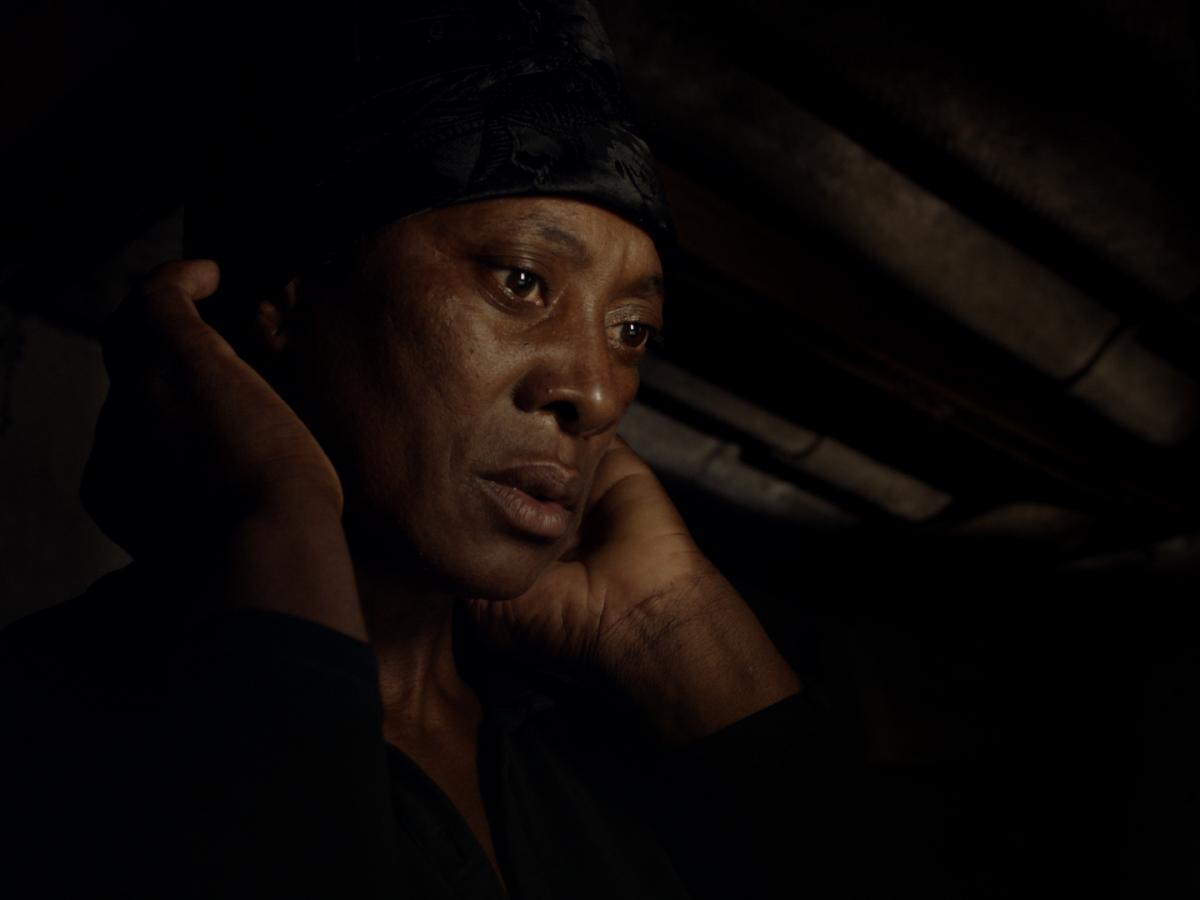

Yet the journey from shadow to shadow is not a simple liturgy. There is indeed a story being built within these repetitive-looking episodes. A story that is first and foremost visual. The apparent immobility of this liturgical time and the obscurity of this nightly parade of shadows are pierced by an implacable light: that of Vitalina’s gaze, the flame that burns in the two white spheres of her bulging eyes, on this black face that sometimes barely stands out in the half-light. These wild eyes watch the shadows file past and seem to see through the lies of their ceremonial attitudes and words of condolence. It is as if they can see clearly what the visitors are nonetheless only whispering about the deceased’s other wife, the one who was at the funeral. We don’t know if Vitalina has heard their words, but her eyes read the lies: those who attend the ceremony are in fact false witnesses. And she abruptly discards her polite grateful-widow mask to dismiss them without mercy. The seemingly frozen time of liturgy thus gives way to an equally classical fictional plot: we are dealing with a trial, in which Vitalina conducts the investigation and draws up the charges. Later she will say that she “does not lament cowards” to another false witness and true accomplice: the visitor who arrives unexpectedly and opens the door with his keys as if it were his home. And he, indeed, shared Joaquim’s flat, his life and his pleasures. He shared his lie, above all. He talks in plain terms about the letters they wrote together to Vitalina. Hearing him talk, those familiar with Pedro Costa’s films automatically think of Colossal Youth and all the poetry of that letter to the distant dearly beloved that Ventura kept intoning and that he vainly tried to teach Lento: a ready-made love letter that is nevertheless sincere, since its very impersonality reflected these men’s shared destiny. But here, the duet-writing becomes a lie, becomes identified with the imposture that all these men are complicit in. The nocturnal visitor appears as a double of the deceased, and this process extends the one Vitalina began, once the funeral ritual had been completed, with regard to the deceased, whose death is just one more abandonment in addition to all the previous ones: the departure for Lisbon where, of course, he had to earn the money to bring her over; the house back home, established together and left unfinished; the impromptu departures after short stays that left her pregnant with children he would not take care of. His betrayal is the betrayal of all those men who left, full of energy, to provide wife and children with the means for a new life. All of them quickly let their dreams wane in shanty towns where they rushed into dwellings without light, with sweating walls and crumbling ceilings. These hard-working peasants, brought up with a love for land and family, have become men without faith, workers incapable of building a roof over their heads, cowards incapable of building a life for themselves, traitors who have not only forgotten their beloved wives but also the very meaning of the word love by getting into bed with the women of the streets who have the advantage of just being there. They have fled work on the pretext of going to look for work; they have become lazy, deserters of their own lives. They are, in short, the proletarian version of those young property owners or idealistic bourgeois that Goncharov or Chekhov had shown, slowly getting buried in the routine and parochialism of Russian provincial life. In Horse Money, Pedro Costa put Irina’s (of Three Sisters) last words into Ventura’s mouth, hoping that the suffering of their lost lives would turn into joy for the generations to come. Here, when hearing about the last time fat Joaquim was seen, with slippers and grown-out dreadlocks, we think rather of Oblomov’s degeneration, puffy and sagging, as if in a coffin, in the comfortable rut that has been arranged for him by his landlady, a vulgar woman he took to wife so that he would never have to move again.

The film, therefore, does not unfold a simple service for the dead, but the implacable process of a life already similar to death. He unfolds it from the perspective of the only character who did not give up, who continued to work the land, to build her house, a family and a future, while all the cowards buried themselves in cellars with drinks, side businesses and easy companions. This leading role for a female accuser is what sets Vitalina Varela apart. One could certainly say of all the Fontainhas films that they drew up an unforgiving charge against the capitalist and neo-colonial system that had torn away Cape Verdean peasants from their land, their families and their loves, in order to have them risk their lives on the construction sites of Lisbon and pine away in the shanty towns around it. But Ventura lived the story of his work and suffering with the dignity of an exiled king. And Lento, at the end of Colossal Youth, took on the haughtiness of a judge that had returned from the underworld to condemn the living. It is true that, in the lift scene in Horse Money in which a soldier-statue, a symbol of the Carnation Revolution, had to respond to what that revolution had done for men like Ventura, a voice from elsewhere asked Ventura in return what he had done with his own life. But here it is a well-individualized voice that takes charge of the accusation and asks all these fallen men the brutal question that no well-mannered left-wing filmmaker would dare to ask migrant workers, knowing the answer all too well: they are not the guilty ones, the system is. And it is the system that must be judged. But Vitalina does not know the “system”. She only knows men who have made a promise and who have betrayed that promise; who have betrayed her for the very reason that they are men: beings who can always go away, leave their home, fields, wife and family behind because they are given the privilege of travelling, which is reserved for those who are in charge of preparing the future; beings who, once far away, can still use the solitude of exile, the gruelling labour, the exploitation and the wounds suffered for that famous future as an excuse for justifying this small, miserable and forgetful life these men have cobbled together. Vitalina’s gaze and words redistribute the game: it is not about male workers and capitalism exploiting them. There is only one and the same world: the world of men – males – who agree to capitalist exploitation if it allows them to live their misery comfortably among themselves and to confirm their privilege over women who are left, somewhere far away in a domestic underworld, to take care of the land, the house and the children. Everything is said in Vitalina’s few sentences that refute the funeral oration pronounced by the priest, Ventura, who represents the male world, in order to pay tribute to the memory of Joaquim, the worker who has finally found peace after a life of toil and moil. This oration is nothing but the discourse of the descendant of Cain, the man “always in favour of men”. “I have closed his eyes full of bitterness,” the priest says. With a scathing sentence, Vitalina then wipes out the conventional formula that leads the hard-working man to his final resting place: “Upon seeing a woman’s face in a coffin, you cannot imagine her suffering.”

Not even in death is suffering equal. But Vitalina turns this unequal relationship against the men who complacently exchange the roles of suffering worker and consoling priest. The suffering of men who have given in and that of women who have kept going are incomparable, as are the house built back home for the future and the poorly built hovel of slum-dwellers. Pedro Costa subscribes to this reversal of power by which the woman judges and condemns the world of men. He agrees to it as to the light that pierces the darkness. But the simple relationship between light and night makes up an unequal dramaturgy. And art does not thrive on inequality. The filmmaker must find a way to restore equality. In order to do so, he must restore dignity to those who have been pushed even further into darkness by Vitalina’s gaze and words. Their bodies must be given a way of being that redeems their laziness: a way of being attentive to doing the right thing. As weary and disillusioned construction workers, they may have lost that. But they can win it back in a practice that is new to them, that of the actor. They can, just like Vitalina, learn the text that slowly took shape while Pedro Costa spoke with Vitalina and with them and whose verbal mass Costa gradually blended with his own literary and film culture and synthesized into possible scenes. They can say the text like actors of a new genre. They are telling their lives, but not in the usual conversational tone. Nor in the manner of those professional actors who try to act “naturally”. The latter would undoubtedly try hard to put themselves in their characters’ shoes, express the frustrated feelings of the inhabitants of these neighbourhoods and take over their slipshod language. Joaquim’s companions do the exact opposite here. They use an even and continuous phrasing that recalls the manner of the tragedians. As they don’t need to adopt the tone of the people, they can concern themselves only with giving the words and their combination a power of their own, which will always be superior to whichever grimace or clamour. They put their lives into words as if it is a role they have rehearsed at length and which they endeavour to reproduce without fail. Hence, as always with Pedro Costa, the extraordinary concentration of faces, where the mere effort of those trying to remember their text opens up an abyss of thought and endows the simplest words with unprecedented depth: “I washed him, I shaved him, I changed him, I gave him soup.” The man who says these words, upright, arms glued to his body, right after having prosaically flushed the toilet and adjusted his trousers, endows this equally prosaic evocation with the power of gospel words: “I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in.” And young Ntoni, who lives on the street with a depressed girlfriend and collects leftovers from the supermarkets – more than leftovers, probably – also finds the right tone to amplify the words that correct Vitalina’s irrevocable judgment: “We may be traitors, but we also know how to help our friends.”

For the duration of this performance, the fallen workers have become trustworthy men again. By remembering their text and the right way to say it, they have, for a moment, regained the capacity to be men who remember, men who do not break their word. However brief this reconquest, it is nonetheless decisive. The filmmaker has confidence in and restores the dignity of those in whom Vitalina has lost all confidence, those she has condemned. The film is made of this tension between a long process of condemnation and a series of short performances of redemption. That is why the rage that animates Vitalina’s inquiry will end in a kind of peace. In spite of her, in a way. Vitalina indeed refuses any reconciliation. There is nothing left of her love apart from a grief that she wants to be endless. She announces that she will forever stay in this country which Joaquim had vainly withheld from her. It is her revenge, and she intends to wield it at her own expense by shutting herself away in the hole where he had buried himself to flee from her. But the filmmaker cannot leave Vitalina like this. He cannot let her grow old in the house of the deceased even if his friends, who have become worthy men again, keep their promise to repair the roof. The film will therefore take her to Cape Verde, where we will see a younger-looking Vitalina dressed in bright colours blithely climbing the cinder blocks and lovingly putting her arm around her young worker husband before casting a last confident gaze towards the sea and the future. Of this love, indeed, an image remains that nothing will ever erase.

This text was originally published as ‘Deux yeux dans la nuit. Vitalina Varela de Pedro Costa’ in Trafic, no. 115 (September 2020).

With thanks to Jacques Rancière