Ventura, a Cape Verdean laborer living in the outskirts of Lisbon, is suddenly abandoned by his wife Clotilde. Ventura feels lost between the dilapidated old quarter where he spent the last 34 years and his new lodgings in a recently-built low-cost housing complex. All the young poor souls he meets seem to become his own children.

“It seems to me that we are losing an incredible amount of things that are vital to go on telling the tale. I mean, me being someone who believes in narration. This is the catastrophe we’re facing. We’re left with nothing else but words, with the power of words. I’ve always had a great belief in them, much more than in images. When I say ‘the power of words’, it’s not like there’s a secret meaning to it. Remember the letter in Juventude em marcha? Do you know the sad story of the last days of the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam? The KGB was coming to his apartment to arrest and deport him to the gulag. In a frenzy, he begged his wife to memorize his poems so that the police wouldn’t get hold of them. He could no longer write them down, do you understand? Perhaps you’ll disagree and say it’s not yet that tragic; but I’ll tell you that if we don’t grab the words now, they will be taken from us. And the feelings too. Then there will be no more films. We’ll have to grab the words quickly because they are being kidnapped. Our people are going mute, amnesic and insane. Our people are being imprisoned and impoverished. The working class – what we used to call the working class – is handicapped, autistic, confused. Insane.”

Pedro Costa in conversation with Martin Grennberger1

“It is true that there has been a certain shift from the beginning Pedro Costa’s cycle, which now consists of four films. The very first film, Ossos (1997), was still a kind of conventional fiction, while the second one, No quarto da Vanda [In Vanda’s Room] (2000), looked like a chronicle, following the character in her room, her drug addiction, her conversations with other drug addicts. Then, in the following film, Juventude em marcha [Colossal Youth] (2006), it appeared more and more clearly that what looks like a chronicle of the life of some migrant workers was entirely a fiction, meaning that it was composed, if you will, of theatrical performances, of little scenes that have some kind of Brechtianism about them, though not in the same way as in Straub. Scenes in which the characters play or replay moments or episodes of their own life or the life of their friends and acquaintances, of all the people who came from Cape Verde to work in Portugal. With each new film, these theatrical performances become epic – something that looks like a journey into Hell, something reminiscent of the journey into Hades in the Aeneid or the Odyssey. That’s what Pedro Costa wants to show: these people are in our world, living amongst us, even though, at the same time, they don’t really live amongst us, they are a kind of living dead. There is a moment at the end of Juventude em marcha when they appear to be ghosts and this ghostly presence becomes a way of illustrating their situation.”

Jacques Rancière in conversation with Stoffel Debuysere2

“Over time, and through Costa’s patient, insistent observation, Ventura “comes to presence,” in the Heideggerian sense. He is allowed to transcend the categories that both well-intentioned liberal cinema and the social bureaucracies have slotted for him. Colossal Youth bathes him in shafts of almost heavenly light, bringing him forth and challenging the imposed, even ritualized invisibility that society has typically imposed. Likewise, Vanda, the garrulous single mother and former heroin addict, gets to launch into a manic monologue that, over time and through the cluttered verbiage, allows us to see who she might really be – a scattered thinker, a loving but distracted mother, a fighter, an effortless comedienne. This isn’t to say that Costa idealizes his subjects. We clearly perceive Vanda’s mania, just as Ventura's endless repetitions of the poem following Clotilde’s departure speak to his traumatized frailty. But Costa and his film embrace these contradictions as part of the human tapestry, and nothing to fear. (Likewise, Ventura's run-ins with the museum guard, himself a former slum-dweller, are socially charged, but Costa refrains from judging the guard’s obligation to give Ventura the bum’s rush.) Like Straub and Huillet before him, Costa practices a cinema of exacting materialist rigor, and this allows him to re-see the world for us in ways that have significant consequences for how we, his audience, might behave in the world. After all, as I watched Colossal Youth, I had to think about my own reactions and where they came from. I had to wonder why I was surprised when Lento dished up a plate of food and, instead of digging in, passed it over to Ventura. I had to remember that part of the reason that Costa’s hieratic lighting effects were possible was the fact that his subjects were living with holes in their ceilings. They must let the rain come in, but Costa challenges us to remember that they let in sunshine as well.”

Michael Sicinski3

“In other films they’d call it a retake, but for us it’s not: we don’t correct. I don’t think Vanda or Ventura correct. They are writing, if we can say ‘write’ for this kind of work. They reorganise the text in their heads and find different ways to tell it. The great pleasure I get is feeling that we’re all searching at the same time. I really like when you see the effort on the screen. People try to avoid that. The idea is that you shouldn’t see the work. I like to see it. There’s an element of resistance that confronts the viewer, the audience. I think this work, this repetition, is an attempt to exclude the bullshit you see in other films: clever looks, all the unnecessary things. They come up like a monster and we beat them away with a stick.”

Pedro Costa in conversation with Giovanni Marchini Camia4

“Ik ben geen videokunstenaar, ik ben een filmmaker, en een film is een constructie. De onderdelen moeten in elkaar passen, anders zakt het hele ding in elkaar, of erger: het mist beweging en spanning. Elk shot, elke scène hangt af van de shots en scènes die eraan voorafgaan en erop volgen. Je kunt natuurlijk ook zeggen dat elke scène haar specifieke waarde heeft, maar uiteindelijk is film de kunst om momenten op zo’n manier samen te brengen dat ze een verhaal vertellen. Misschien kom ik nu wat reactionair over, maar ik geloof dat de film zijn narratieve basis nooit kan vergeten.”

Pedro Costa in gesprek met Catherine David en Chris Dercon5

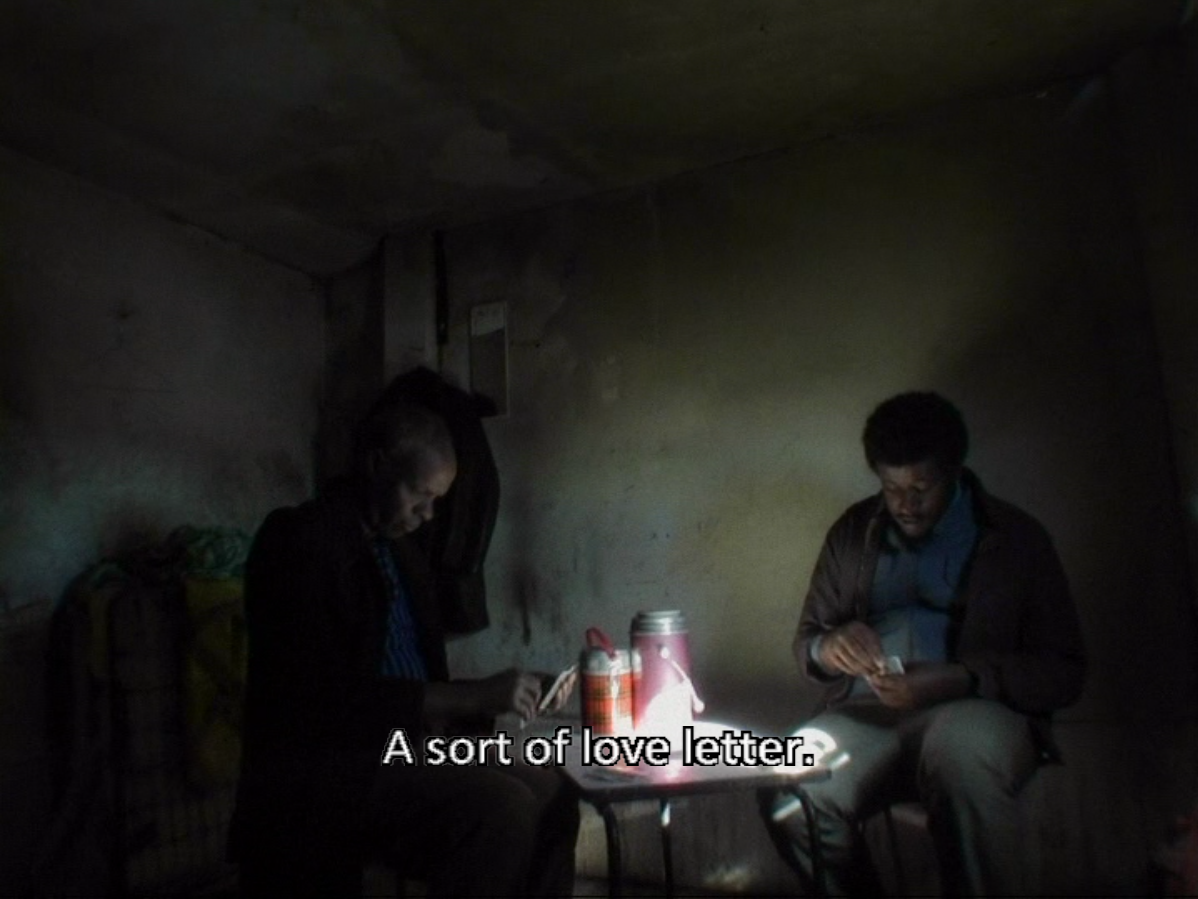

“Hij zit gebogen over een tafel, insisteert gebiedend dat Lento moet komen kaartspelen en gaat voort met het lezen van de liefdesbrief die hij aan Lento wil leren, die zelf niet kan lezen. Deze brief, die verschillende keren luidop voorgelezen wordt is zoals een refrein voor de film. Hij spreekt over een scheiding en over werken op bouwwerven ver van geliefden. Hij spreekt ook over de nakende vereniging die twee levens voor twintig of dertig jaar zal begenadigen, over de droom om de geliefde honderdduizend sigaretten te geven, kleren, een auto, een klein huis gemaakt van lava, en een driestuiversboeket; hij spreekt over de inspanning om elke dag een nieuw woord te leren – woorden waarvan de schoonheid perfect geschikt is om deze twee wezens te omhullen zoals een zijden pyjama.”

Jacques Rancière6

- 1Pedro Costa in Martin Grennberger and Stefan Ramstedt, “In the Shadows of Catacombs. A Conversation with Pedro Costa,” Sabzian, 16 October 2015.

- 2Jacques Rancière in Stoffel Debuysere, “On the Borders of Fiction. A Conversation with Jacques Rancière,” Sabzian, 20 September 2017.

- 3Michael Sicinski, “Another 10-day, 50-film clustertiff,” The Academic Hack, 2006.

- 4Pedro Costa in Giovanni Marchini Camia, “Interview with Pedro Costa,” Fireflies, 4 (2016), 55-65.

- 5Pedro Costa, Catherine David en Chris Dercon, “Film in het museum. Een panelgesprek over video en film tussen ‘cinema’ en ‘tentoonstelling’,” De Witte Raaf, 2007.

- 6Jacques Rancière, “De politiek van Pedro Costa,” Sabzian, 2 juni 2014.