Pedro Costa

The Portuguese filmmaker Pedro Costa made his first film, Blood, in 1989. In 1994, Down to Earth followed, which was filmed in Cape Verde. Costa came back from the island with a number of parcels and letters from Cape Verdeans he had met there, addressed to their relatives and friends who had emigrated to Portugal. His task as a postman brought him to Lisbon’s Fontainhas neighbourhood, where many migrants were living at the time. After this first contact with the inhabitants of the neighbourhood, Costa kept returning there, filming Ossos in 1997, the first instalment in a series of films he would make with the inhabitants of Fontainhas.

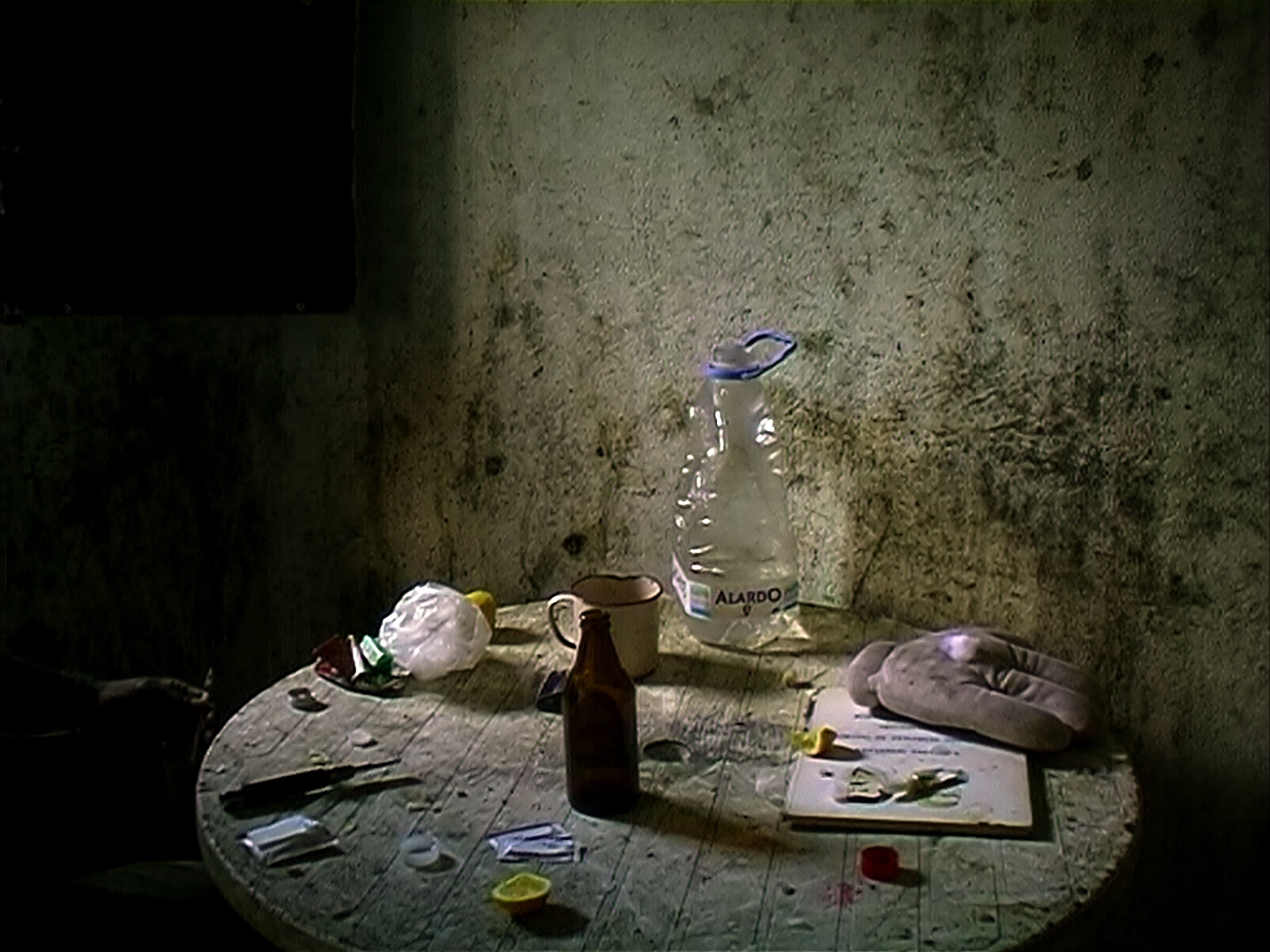

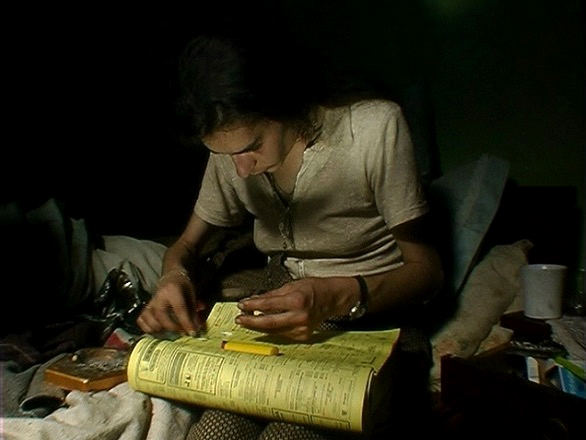

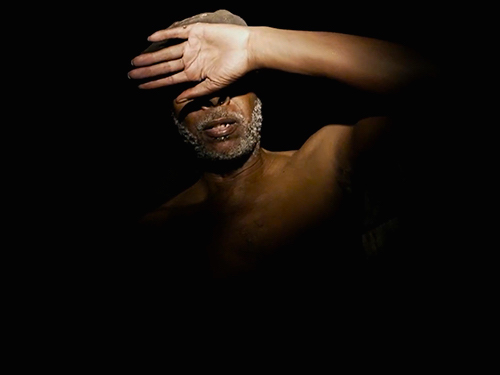

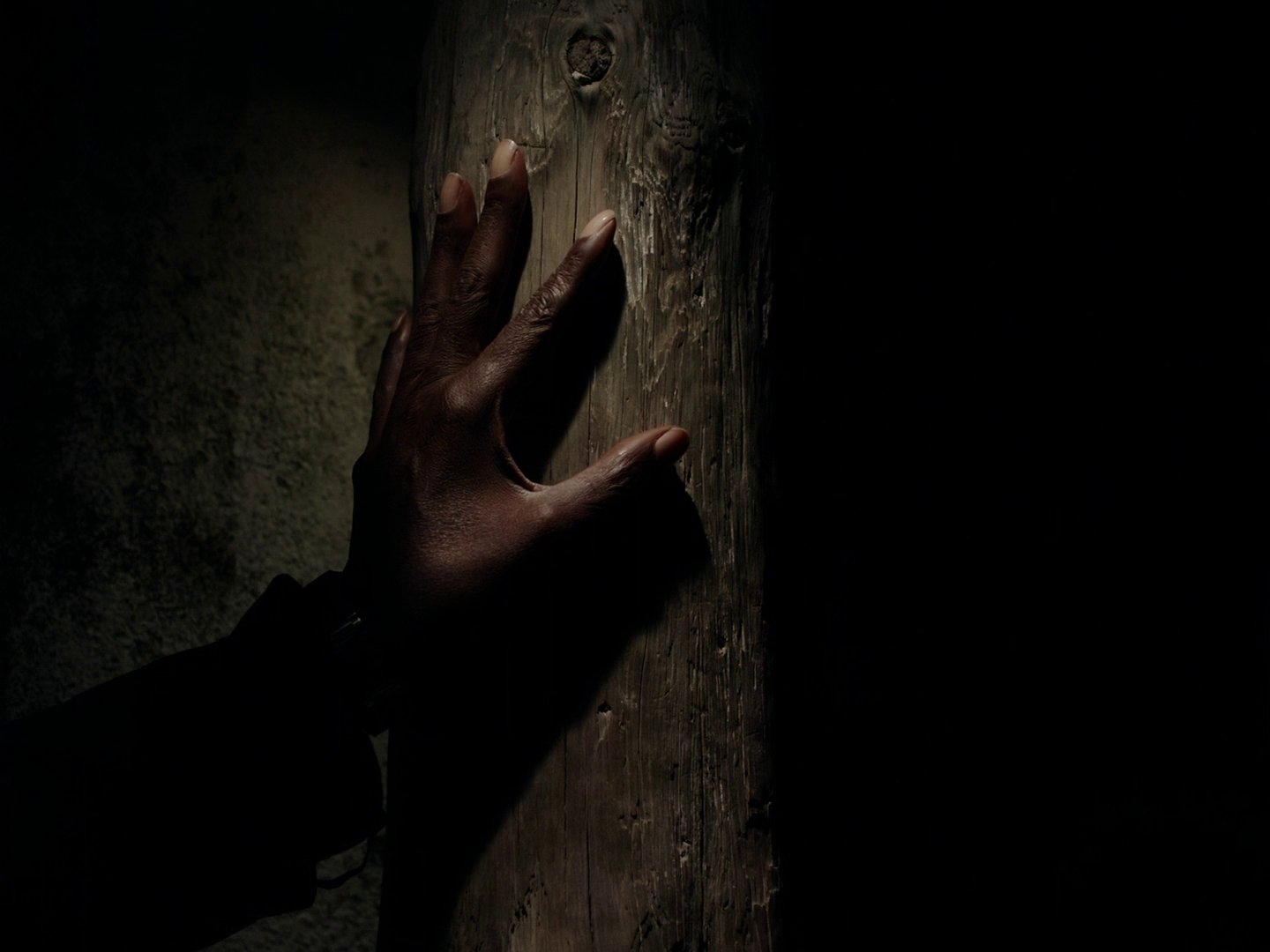

After Ossos, which was filmed with a fairly large and standard film crew, Costa decided to radically rethink his approach. He returned to Fontainhas, alone this time. Unlike his previous work on 35mm, Costa started filming on MiniDV with the newly released Panasonic DVX-100, which resulted in the three-hour film In Vanda’s Room (2000). To date, three more full-length films featuring the residents of this neighbourhood have ensued: Colossal Youth (2006), Horse Money (2014), and Vitalina Varela (2019).

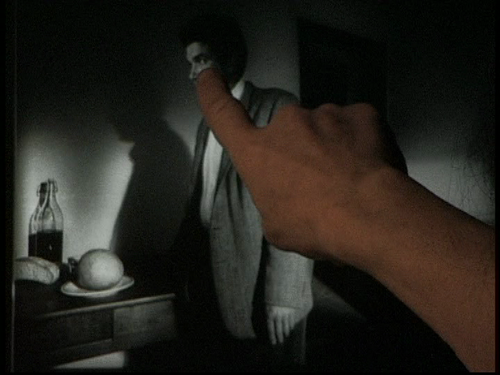

Besides his feature-length films, Costa has also made a number of short films with the inhabitants of Fontainhas. His most recent short film, As Filhas do Fogo [The Daughters of Fire], was released in 2023. In 2001, he also made the feature Where Does Your Hidden Smile Lie?, in which he filmed Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet during their third reworking of the montage of the film Sicilia!. In 2009, he made Change Nothing, a portrait of the French singer Jeanne Balibar.