Week 16/2023

What does it mean to view filmmaking as a political act? Three filmmakers each approached militant cinema when they documented social struggle as an indictment, as a tool of contemporary historiography or as a laboratory of the future.

In 1976, Barbara Kopple listened to the radio and heard about a miners’ association in Harlan County, USA, that was fighting for the right to have a union. She loaned some money and went to film the Miners for Democracy. Kopple’s involvement in the movement was not only through filming. She said: “We wore machine guns with semiautomatic carbines.”

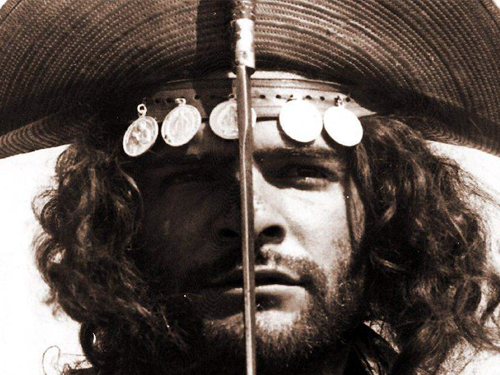

Combining political activism, film criticism and filmmaking, the practice of Brazilian Glauber Rocha as an artist and activist was intertwined. Black God, White Devil (1964) accounts the story of a man who kills his corrupt employer and becomes an outlaw who starts to venerate a violent, self-proclaimed saint. Stoffel Debuysere wrote that “in Glauber Rocha’s work, the myths of the people, prophetism and banditism, are the archaic obverse of capitalist violence, as if the people were turning and increasing against themselves the violence that they suffer from somewhere else out of a need for idolization.”

Relaxe (2022) is the first film of Audrey Ginestet, who is also a bassist in the band Aquaserge. The documentary is not about Aquaserge but about the band’s clarinetist, Manon Glibert, who was arrested in 2008 for ‘criminal association for the purposes of terrorist activity’, sabotaging high-speed lines in France. What came to be known as the group the ‘Tarnac Nine’ consisted of five women and four men who moved to a rural area in France in order to live communally, away from consumerist society. Audrey Ginestet made a portrait of Manon while she prepares herself for her trial.