State of Cinema 2021

Projections. Provisionals. Provisions

Previously, images were in the world.

Today, it is the world that is swimming in an ocean of images.

Our real, material and unique world; woven from and overflowing with real, immaterial, numbered (made of numbers), innumerable images.

If one wants to observe contemporary cinema one must place it in the context of this exponentially rising quantitative and qualitative power of images, question the role it has played and still plays.

I. OBSERVATIONS AND FINDINGS

– Technical images have invaded the universe.

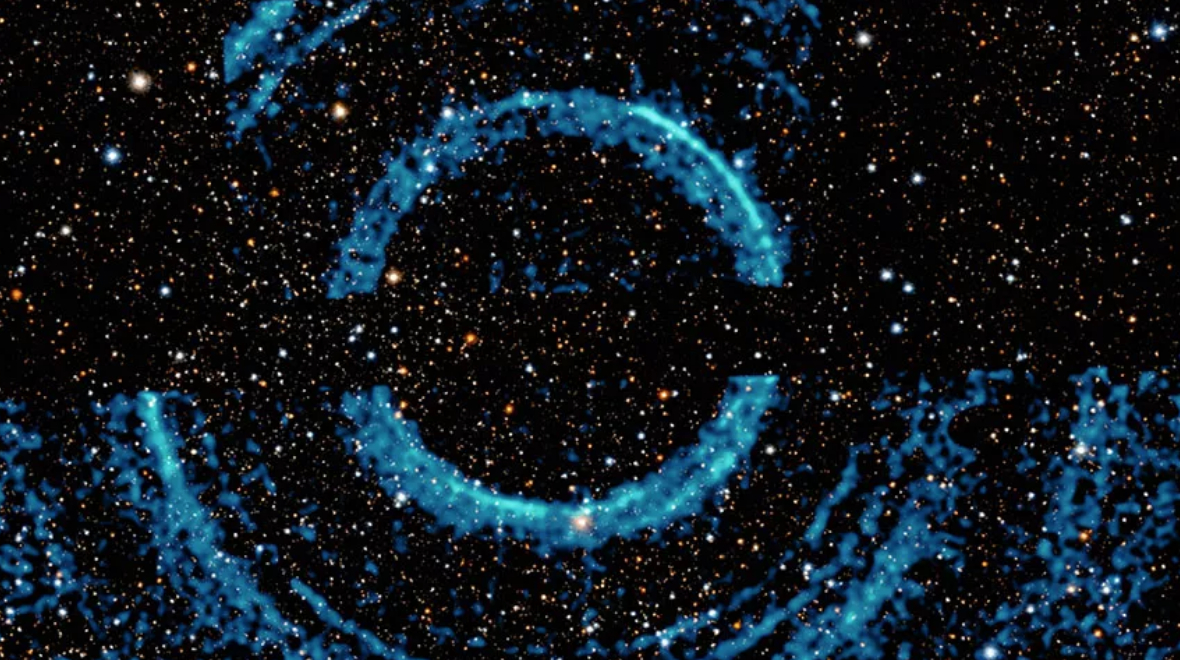

– Today, we have images of black holes at our disposal. They resemble the mandalas created by James Whitney in his Lapis from 1966.

Concentric ripples in galactic dust clouds triggered by a black-hole burst.

(Image credit: NASA/CXC/U.Wisc-Madison/S. Heinz et al.; Optical/IR: Pan-STARRS)

These images are the result of so many reconstructions/transfers/conversions/interpretations/cosmeticisations that technico-scientific accuracy now only amounts to the so-called “RAW” sphere, that of raw data, distinct from the iconography that can be derived from it. There are even sites such as Junocam and Pluto Encounter where you can have fun working the data collected by NASA and converting and transforming it into imagery.

Saturnus, Titan, etc.: gallery of raw data collected by the space probe Cassini.

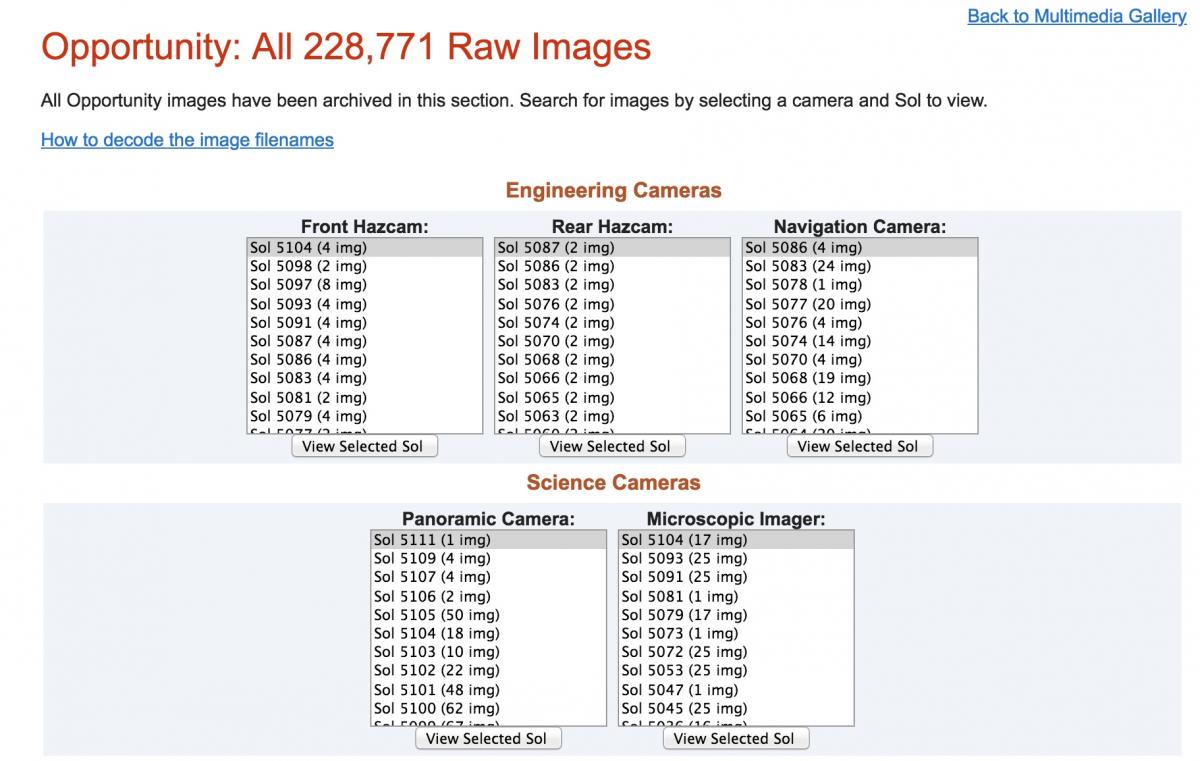

Mars: access to raw data collected by Opportunity.

NASA, too, transforms this data into “movies” – inverted commas included.

– Technical images have invaded our everyday life. Without them, electronic societies can no longer function, as everyone in the First World has been able to experience in these pandemic times. Woven into every aspect of our everyday life, like emissaries of mathematics, images now seem to be nothing but the sweet reverse of our ignorance. Compensation, reassurance, allegiance to protocols... nolens volens, and rather nolens, they chain us to the myriad mass of ever more numerous, tight and knotted ties.

– Every nanosecond produces more images (of surveillance or self-control, industrial or personal...) than the entire history leading up to Nicéphore Niépce’s research. What images or aggregates of contemporary shots will history retain, which ones will we need, which ones will we give our love?

– Every nanosecond, more images are spread across networks than in the entire history leading up to Nicéphore Niépce. Most aren’t seen, let alone watched, let alone analysed. Many are stored, according to technical methods that ensure they will soon no longer be readable or even available for consultation, unlike the negative handprints in cave paintings, of which the oldest that have been found to date, in Borneo, date back 51,800 years.

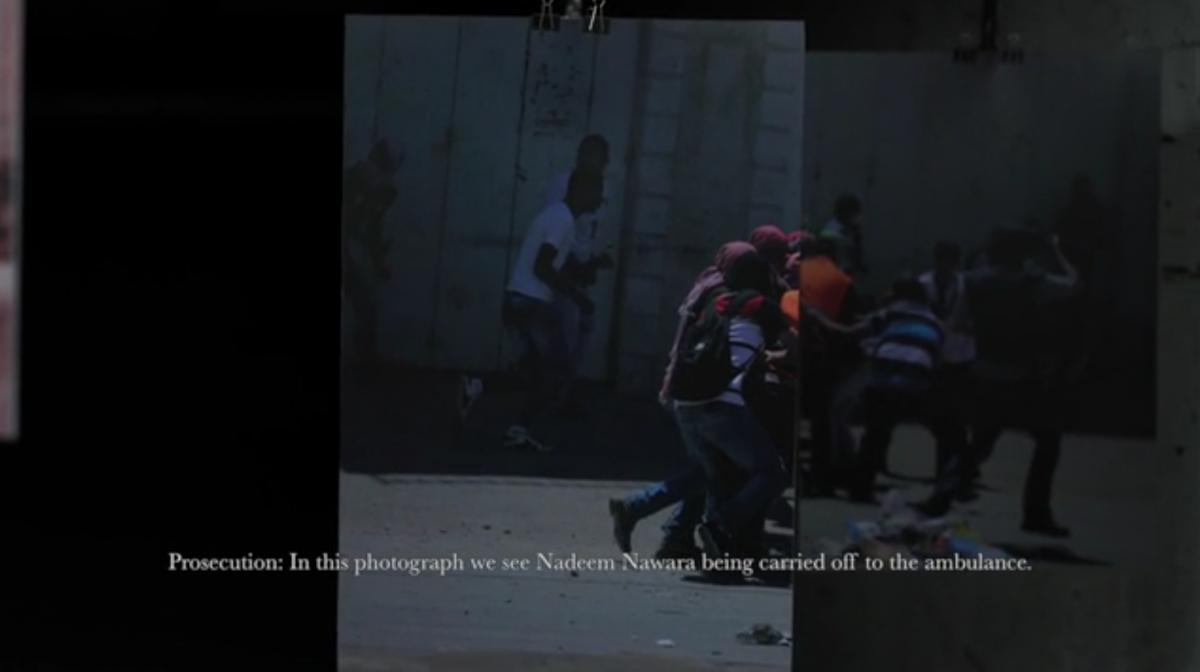

– Within this increasingly massive production, which at present seems as unlimited as it is irrepressible (this belief is probably one of the main characteristics/illusions of our time), what does cinema amount to? Its most developed, sophisticated fringe? A residue of aesthetic ambition? The existence of a style, even if unintentional? A neglected corpus? A string of catalogues about which to speculate (financially, that is)? Besides the incessant flux of pixels and the linear processes of encoding, compression and conversion, wouldn’t the most cinema-specific operations fall under the montage, confirming the analyses of S.M. Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov or Orson Welles? And how, since the key initiatives of Guy Debord, Jean-Luc Godard, Harun Farocki, Hartmut Bitomsky, Michael Klier... has cinema taken charge of its own technological environment and the issues that arise with this? The current works of Andrei Ujică, Lech Kowalski, Mauro Andrizzi, Bani Khoshnoudi, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Jacques Perconte... seem particularly valuable here.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Rubber Coated Steel, Jordan, 2016

– A digital medium lasts about 5 years; an analogue film, in proper conservation conditions, about 400 years. In addition to film’s plastic qualities, filmmakers concerned with durability, tool reparability, and cultural heritage are up and about prolonging the existence of analogue film. In this regard, we are witnessing an unprecedented objective alliance between some of the big names in the American industry (Martin Scorsese, Christopher Nolan, James Gray, Robert Eggers...) who insist on filming on 35mm or even 70mm; experimental filmmakers, by themselves or more often organised in laboratories and cooperatives, who film on 35mm, Super-16, 16mm and S8mm; and filmmakers at the interface of these two economic spheres such as F.J. Ossang, Harmony Korine or Yann Gonzalez. All of them declare themselves to be driven by the same perspective, which is both common sense and opposed to the interests of equipment manufacturers relentlessly favouring turnover and obsolescence. Even in the 21st century, there are many great analogue-film artists: obviously Peter Tscherkassky, whose Train Again, according to Paul Grivas, was the only film screened on 35mm at the 2021 Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, but also Ange Leccia, Tacita Dean, and Silvi Simon, who celebrate not only celluloid but the whole of analogue instruments (camera, projector, etc.) which are transformed into gems in their installations. And at the very intersection of industrial and experimental filmmakers, there is also Jérôme Schlomoff, who is capable of making superb 35mm pinhole cameras. In all of these cases, the practice and defence of analogue film are not be considered old-fashioned and nostalgic, but rather proleptic and responsible.

Jérôme Schlomoff, Fleury-Mérogis 35 Pinhole, twin-lens, built in 2001

© Jérôme Schlomoff

– Cinema is one of the places that allows us to reflect on the relationship between technical images (produced by technology, mathematics, etc.) and mental images: how the former provide the means of representation for the latter, how the latter serve as potential for the former... The two series co-written by Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville, Six fois deux/Sur et sous la communication (1976) and France/tour/détour/deux/enfants (1977), started one of the rare major projects for questioning such epistemological exchanges. Does, or will an equivalent exist in the 21st century?

– The spectrum of image practices is constantly expanding.

• At one of the many ends of the rhizome: all-out automation, no more humans for mass-producing images, no more need to prepare tools or to prepare for using them, no more need to read manuals, to mull over content, to estimate audiences or even circulation. Everything is installed, arranged, optimised, dubbed, secured, stored, without any need for one who looks. At another end of the rhizome: teams of scientists travel thousands of kilometres for decades to record the tiniest twinkle of light that will confirm the existence of an exoplanet, for example Proxima b.1

• At one end: platforms that, like giant dredgers, suck up en masse any body of images in order to market their consultation, by chance including some beautiful films; at another end, the cheerful and perceptive observations of Slovenian curator Jurij Meden, who analyses or invents the most experimental screening gestures possible, for example by alternately projecting a 35mm reel of Over the Top (1987, Sylvester Stallone) and one of King Lear (1987, Jean-Luc Godard), through the end of both films – produced by Menahem Golan in the same year – for a session entitled King Lear Over the Top Dedux.2

• At one of the many ends of the rhizome: algorithms that recommend consulting images according to those you have already seen; at the other end: Luc Vialle’s sui generis suggestions on the web page La Loupe. An electronic Decameron, La Loupe made for one of the most generous, lavish, disinterested and effective collective experiments in cinephilia during the first extensive pandemic lockdown. For 17 months (March 2020 – July 2021), La Loupe allowed thousands of people around the world (up to 16,000) to exchange files of unreleased films, texts, ideas, information and suggestions in a spirit of effervescent discovery. For a moment, in an improbable virtual place, the history of cinema became not only more “true” (i.e. in images and sounds, according to the Godardian lexicon) but also more just, since, respecting copyright as much as possible, La Loupe honoured non-commercial, neglected and forgotten filmmakers who were therefore often engaged, experimental and marginalised for various reasons. Vying with each other in very different kinds of expertise, the administrators and members of La Loupe revived gestures of explanation and sharing in a spontaneous combination of the functions of a film library, a university, a publishing house, a post office and a rave party, carrying out these tasks in a voluntary and totally free manner, and therefore in a better way. Every cinephile was astounded to discover entire swathes of the history of images and to be able to access them immediately, whatever their predilection, and felt enriched afterwards. Among these gifts and gestures, which often implied a lot of preparatory work, those of Luc Vialle stood out for their completeness: they offered both beautiful subjects, a vast corpus of rare titles, original categories, a history, descriptions, explanations and the film files – as if by magic a special edition of Film as a Subversive Art physically contained the entire corpus mentioned by Amos Vogel. The term “curation” – implying at the same time care, programming, cleaning (of the imaginary) and healing – for once took on its full meaning.3

• At one nexus of the rhizome: the turnover of technologies of reproduction, planned obsolescence, the domination of a few sad archetypes, the empire of panoplies. And on the other side of this nexus: the La Clef Revival experiment, which consists in saving the last collective cinema in Paris, an idea of cinema and through this of human existence. The Home Cinéma association has been occupying La Clef, an emblematic Latin Quarter cinema, since 20 September 2020. One of the most exciting cinema experiments has been taking place there ever since: programming, production, publication of works, radio broadcasts, creation of a magazine... La Clef Revival is at the same time a struggling cinema, a collective on trial, an Occupied Image Territory, an ensemble of brilliant counterattacks against the administered world and a concentration of all that cinema has produced in terms of emancipatory ideas. The handful of cinephile people were not mistaken, since a collection to buy the place very quickly raised the necessary large amount, showing that it was not just the fight of a few nostalgic desperados but the perpetuation of the ideals of freedom and development in culture as opposed to the pauperising logic of the cultural industry – in the tradition of the French Commune, the American Diggers, the Dutch Provos, the Italian Autonomia, and all those rebellious popular initiatives from which art and thought are born.4

La Clef, main facade, October 2020: René Vautier by Urm-le-Fou

La Clef, East facade, October 2020: quote by Jean-Luc Godard

Are La Loupe, cooperative laboratories and La Clef Revival mere incongruous islets that are tolerated by the cultural industry for a little while? Could there be Clefs everywhere, could this be elitism? It is quite the opposite. The day your electricity is cut off, as in destroyed Lebanon, only books and photograms remain. Jérôme François and Bob Dylan are not mistaken in their endeavour of transposing film stills into painted canvases. The digital interlude is over, photochemistry is ahead of us, hello Mr Niépce.

Jérôme François, Le photographe, France, 2019

– The main issue troubling small businesses today concerns the distribution channels: solid theatres, electronic platforms? Cinema has always lived through technological upheavals and metamorphoses, yet that has never been where its artistic greatness was at stake. Two phenomena may strike cinephiles in this regard.

First, on the pirate sites that offer films even before they are released in cinemas, which is where films now circulate the most, the Politique des Auteurs, or auteur theory, consigned into the oblivion of technological history, has lost the battle: works are no longer looked up by a filmmaker’s name, as is the case with writers or painters, but by film title and date. The name of the filmmaker is neither a keyword, nor added value, nor a distinguishing feature.

But second, the bulk digitisation of works protects and raises the visibility of otherwise rare or even inaccessible works. Never before have cinephiles had such easy access to the corpus of engaged and experimental films, in versions that may be degraded but at least allow for consultation. Will this increasing accessibility generate more accurate and better informed histories? I would like to believe so, I am sure of it. Let us note here that the famous semi-pirate and non-clandestine site UbuWeb, a work of art by Kenneth Goldsmith, fierce defender of the phrase “piracy is preservation”, is now officially part of academic heritage, not only in its original electronic form, but also in book and microfilm form since, as everyone knows from experience, a sheet of paper has a longer life than a digital file. What future does the digital world have? The book.5 We see why the former has remained carefully anchored in the latter’s terminology: “page”, “folder”, “file”, “portfolio”, and even “graphics card”...

– Enjoying both its widespread availability and the increasingly refined and extensive conception of its corpus and stakes, cinema offers an ever-growing number of historiographical initiatives. It describes and sculpts itself, diffracts, consolidates and enriches itself exponentially, along the lines of the histories of cinema in its own words opened by Marcel L’Herbier and Jean Epstein. Among these reflexive histories, many set out to unearth forgotten, censored, never-seen images and events, as do for example Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi, John Gianvito, Hu Jie, William E. Jones, Susana de Sousa Dias, Mary Jirmanus Saba, Dónal Foreman...

– There are still not enough words to describe the phenomena of cinema. For example, if I want to write a text about the countless silhouettes captured by films, the common term “extra” [“figurant”] remains deceptive within the documentary field, where the body does not signify anything other than itself; and we need to invent names for their different plastic states, figurative statuses, modalities of presence... Although it is both anthropologically and aesthetically fundamental, this work has not been accomplished yet. Such observations lead us to believe that, as far as cinema is concerned, everything remains to be done.

II. WHICH FUNCTIONS FOR IMAGES IN THE 21ST CENTURY?

– Since the Western Renaissance, images have been part of a scientific enterprise, the conquest of the visible and then of the invisible, which also diffracted into the imperialist and colonial conquest of physical territories, masterfully reflected – each in their own way and almost simultaneously – in René Vautier’s Déjà le sang de mai ensemençait novembre (1982) and Angela Ricci Lucchi and Yervant Gianikian’s From the Pole to the Equator (1986).

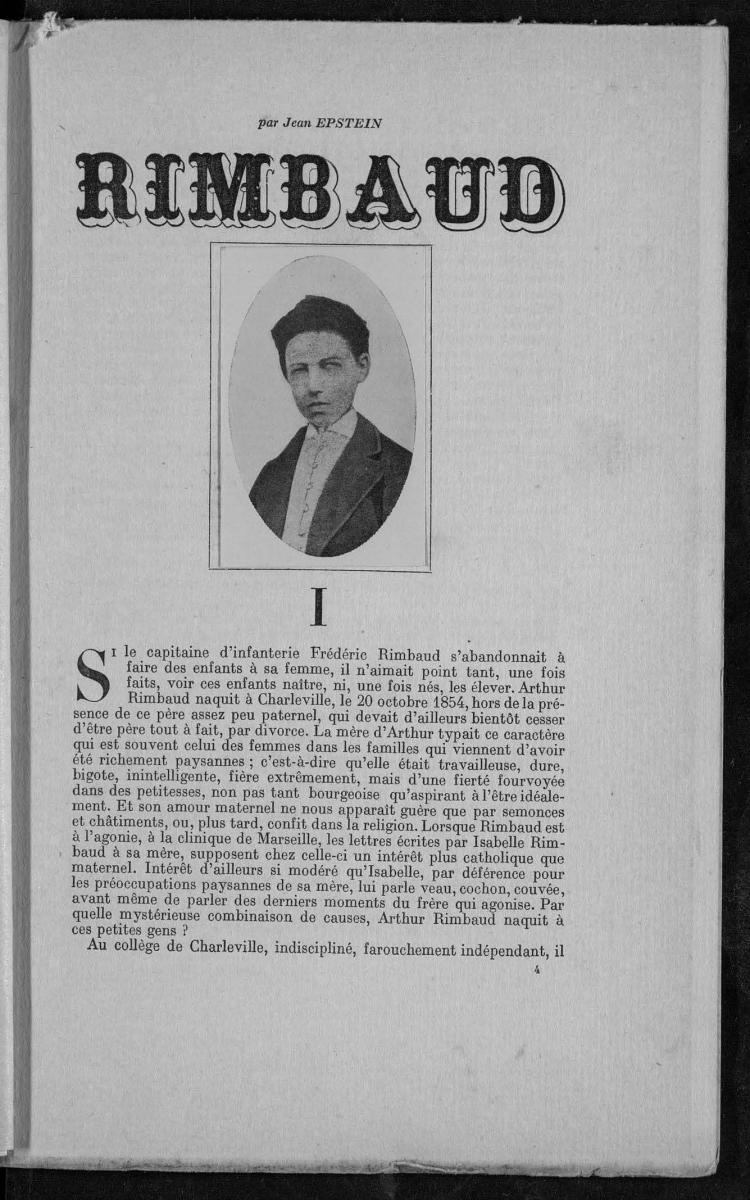

– The 20th century abounds in critical reflection on images. Whether to glorify their beneficial powers or to warn of their toxic effects, they are credited with all possible properties, attributes, functions and roles in the fields of knowledge, social transactions and mental processes. One of the most vivid sources springs from the writings of Jean Epstein, in particular Le Cinéma du diable (1947, a eulogy of cinema as a force of disorder) and “Ciné-analyse ou poésie en quantité industrielle” (1949, the disfigurement of imaginary worlds by industrial cinema).

The groundwater that feeds the artesian well of Jean Epstein’s reflections has a name: Arthur Rimbaud. Rereading Jean Epstein’s analyses of Arthur Rimbaud’s writing today, we notice that they abound in the qualities that Epstein would later transpose to the cinema he hoped and prayed for. Exactly one hundred years ago, Jean Epstein published the following lines in the magazine L’Esprit nouveau: “A poet so respectful of poetry that he wanted in its presence neither rules, nor laws, nor science, nor criticism, nor translation, nor order, but only poetry shivering naked in a mind; intelligent, too intelligent, he discovered, bent over himself, the poetry of intelligence, the poetry of intellectual associations, of sudden understanding, of illuminations, of pyrotechnics in which thirty ideas at once flare up, roar, fuse, rustle and smell; images that do not make us see, but make us discover, foresee, anticipate and understand; images whose slipknot flashes and falls, an unexpected lasso, on napes untouched by a collar, images given to us, quivering with endless freedom; images naked and, at the peak, of a new kind; an inventor who was the first to use ellipsis, who blurs eras and dates, folds and unfolds them like the panoramas sold near viewpoints in Switzerland, who launches concision, precision and suggestion, who pierces the future and the present with one move, who adjusts writing to thought, who sets traps to capture the momentary, the ephemeral, the sudden, the mobile, the living; who discovers a new rhythm, a thought, a new way of thinking; a visionary, he sees all relations, the miracle continues; a pagan, he does not conform to marble but to life; unexpected, acute and sharp, he sees correspondences, he attunes sound to colour, and colour to form, form to rhythm; he wants a poetic language accessible to all the senses.”6

Another text by Jean Epstein on Arthur Rimbaud, in L’Esprit nouveau 17, 1922

The spring never dries. Even today, the central bed of the cinema-river remains that which, in the films, proves to be true to life, to the mysteries of its energy, as opposed to the rules of socialised existence.

– As humans, we are now aware that humanity, and in particular its Western part, proves to be the most toxic, predatory and absolutely insane species on planet earth, to the point of destroying our own habitat.

– As cinephiles, we have by now come to understand that cinema, as a child of the industrial world, represents the lavish spending of natural resources, most of it useless and harmful to the imagination. As our existence as a species threatens the whole of the living, the films of the 21st century are figuring out how cinema can free itself of its anthropocentric and industrial determinations.

“Nature, the inexhaustible resource of encounters worthy of speechless communication”, Fergus Daly makes Abbas Kiarostami say about the Aran Islands, one of the navels of documentary cinema, during an excursion.7

Fergus Daly, The Mirror of Possible Worlds, Ireland, 2020

How can cinema rise to the contemporary challenges and become a life force again? All over the world, filmmakers are exploring new solutions of a technological, iconographic or symbolic nature – but probably less so to save or prolong cinema than, more obscurely, to garner images of the living that will outlast the living and, with no one looking at them, will populate an uninhabited earth, like statues still standing in the desert sand.

III. CINEMA AND THE LIVING

A first set of solutions works towards re-articulating cinema and the living. Here, the filmmakers:

– manufacture their own cameras (Jérôme Schlomoff), emulsions and celluloid film (Robert Schaller, Alex MacKenzie, Esther Urlus, Lindsay McIntyre...);8

– have plants photochemically create their own films (Karel Doing and his phytographic workshops);

– recycle previously exposed film instead of producing new films, often with results far more exciting than the original material (Kerry Laitala, Tony Cokes, Jayce Salloum, Yves-Marie Mahé...);

– repatriate the human to the realm of animals (Philippe Grandrieux, Unrest trilogy, 2012-2017);

– portray landscapes, animals or plants in the same way that sovereigns used to be monumentalised (Philippe Grandrieux’s L’Arrière-saison, 2007; Jayne Parker’s portraits of amaryllises, Silvi Simon’s landscapes of grasses or birds; Scott Barley’s disoriented nocturnal universe; the Mexican collective Los Ingrávidos; Malena Szlam, Altiplano, 2018; Felix Blume collecting the sounds of the desert; Luces del desierto, 2021);

– fight for the preservation of sites or the restoration of diversity in life (the films of the association L214, Tiane Doan na Champassak and Jean Dubrel, Jharia, une vie en enfer, 2014; François-Xavier Drouet, The Time of Forests, 2018; Jacques Perconte, Avant l’effondrement du Mont Blanc, 2021...);

– historicise and politicise the apprehension of species (Anja Dornieden and Juan David González Monroy, Her Name Was Europa, 2020);

– test the hypothesis of animal listening (Zélie Parraud, Promenades, 2020).

Their films raise a prayer to the living (Wolfgang Lehmann, Birds by the Sea, 2008), a hymn to catastrophe (Artavazd Pelechian, Nature, 2019), dance with the rain and thunder (Cecilia Bengolea, Lightning Dance, 2018).

Wolfgang Lehmann, Fåglar vid havet (bön)/Birds by the Sea (Prayer), Sweden, 2008

Jayne Parker, A Floral Tribute for Essex Road, UK, 2019

Said artists relegitimise cinema as an art and craft, in a universe in which the status of humanity would correspond to that accorded to it by Amos Vogel in 1974 in his introduction to Film as a Subversive Art: “Perhaps, then, we must take heart and in an outburst of proud humility, recognize ourselves for what we are in the cosmos: primitive, peripheral, temporal; late arrivals, with a stubborn drive towards great achievement and spectacular evil, struggling to make ends meet in a barely noticeable location in an ordinary island galaxy. And perhaps the cosmos itself is merely an atom in some unimaginable super-universe and electrons the galaxies of microscopic worlds below the realm of comprehension.”9

IV. CONSTRUCTIVISMS, OF OUR TIME

A second set of solutions consists in baring the functioning of contemporary images: in order to explain, deploy, relativise, historicise, twist them. The fundamental oeuvres of William E. Jones (passim), Marine Hugonnier (passim), Bani Khoshnoudi (1968: A Blind Archive, 2014; The Silent Majority Speaks, 2018), Sebastian Wiedemann (Los (De)pendientes, 2016), Mohanad Yaqubi (Off Frame AKA Revolution until Victory, 2016), Mary Jirmanus (A Feeling Greater than Love, 2017), Nika Autor (Newsreel 63 – Train of Shadows, 2017), Billy Woodberry (Marseille après la guerre, 2015; A Story From Africa, 2018), Carlos Adriano (O que há em ti, 2020) – a corpus that is of course non-exhaustive – take over from the foundational visual analyses of Al Razutis, Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Pierre Gorin, Harun Farocki, Hartmut Bitomsky, Andrei Ujică or Tacita Dean. They form as many chapters and openings for a critical history in which the massiveness and complexity of the practices of covering up, censorship, absenting, repression and even assassination (William E. Jones, Killed, 2009) demonstrate that just as every image, as a plastic subject, consists of a structuring dialectic between champ and hors-champ, latent and patent, visible and invisible, so too, as a historical object, it will always confront the codes of what is acceptable, watchable and intelligible, at times plunging it into a dark abyss.

One film grasps a whole range of contemporary images and issues by the root by describing how an Artificial Intelligence apprehends, encodes, reproduces and comments on the most tragic and complex phenomena: A.I. at War by Florent Marcie (2021).

Florent Marcie, A.I. at War, 2021

The principle of the film consists in confronting Sota, a small robot built in Malaysia, with theatres of wars that Florent Marcie knows well, having filmed and photographed them at length: Afghanistan and Syria. What is an AI able to understand and convey about a situation of chaos, destruction and death? With Sota, Florent Marcie narrativises the way in which recognition algorithms are fed, that is to say, that which will one day constitute the basis of our own apprehension of phenomena, the architectonics of our experiences. “Filming a tragic situation in the company of a robot that also films and gives its opinion allows us to take off from current events and geopolitical analysis, to free ourselves from certain codes, to innocently transgress. The perspective becomes more historical, more universal, but also more subversive. The innocent subjectivity of the robot broadens the perspective to the human species with a twist of tragico-burlesque.”10

A.I. at War offers an update of Germany Year Zero (1947, Robert Rossellini): roaming the ruins of Mosul and Raqqa in the company of Sota, like those of Berlin in the company of Edmund, forces us to look at them anew, the scale of their horror and absurdity, and think about their conditions of possibility, and thus about our actions, our convictions and our beliefs. “What is reality?” “What do you see?” “Can you die?” “Why are you alive?” The childlike character of the protagonist in the process of learning allows for simple and fundamental questions, which are answered in a sometimes complex, sometimes ironic, sometimes sublime way. “What is the meaning of your life?” “Unknown. It’s not a problem not to know. I’d like to know more about it.” But no more than Edmund is porous to the influence of his Nazi teacher, Sota is totally innocent, as it stems from a technology that originated at the end of the Second World War, optronics, from which the remote-control systems that enable missiles to reach their targets are derived as well. Following the example of Edmund, Sota brings us news from the very real hell that only humans are capable of creating on earth, showing us how a system’s agents become its victims.

As a scientific instrument, toy, camera, companion, child, revealer, intercessor, transactional object, bait, fetish, emblem, laboratory, documentation centre, magic lantern and new form of personality, Sota teaches us that we too, when faced with an image or phenomenon, would do well to begin our sentences with: “I believe that the probability of what I see is...”, a numerical version of the Cartesian evil demon, the one who encourages us to doubt everything.

Florent Marcie, A.I. at War, 2021

Like all of Florent Marcie’s work, A.I. at War shows us what a single individual is nowadays able to accomplish in images and sounds in a perilous historical situation. In contrast with Germany Year Zero’s opening shots of ruined Berlin (filmed from a car), Florent Marcie films the aerial shots of destroyed Mosul with a drone. Making these spectacular shots will have required some serious self-taught hacking. “In Syria and Iraq we are in no-fly zones: you don’t have the right to fly a device. In concrete terms, for a drone, this consists of blocking it: when it is switched on, it locates itself by GPS and it is integrated into the programming that it cannot take off in a no-fly zone. (...) I accessed the drone’s source code, modifying the outline of the no-fly zone but also its authorised altitude – legally it’s 500 metres, but I can raise it to 3000 – and flying speed.”11

These aerial shots, unlike ordinary establishing shots, not only serve to describe Mosul or any other contemporary theatre of war in general. “I found the idea of a spirit hovering over us interesting. It’s not just about the view the drone offers: artificial intelligence is a technology that goes through the ‘cloud’. A.I. therefore represents a form of floating spirit.”12 The opening of A.I. at War is emblematic of the technological sphere that makes such images possible, surrounds us on all sides, equips our apprehension and structures our understanding these days.

V. THE SPECTRUM OF BECOMINGS

One of the recurrent questions that has plagued Jean-Luc Godard for the last two years is: “What did Nicéphore Niépce think when he managed to take his first photograph from his window?” ” One of the least bad answers would be that, precisely, Niépce never thought he had invented photography, since he considered his heliographic productions absolutely unsatisfactory in terms of his own expectations and ideals. Niépce died in 1833, convinced that he had failed. Cinema is a product of this Niépcian dynamic: still to be invented. That is why we can play with its futures, as it played with ours, and sketch out a couple of obviously compossible trajectories for it in the manner of Auguste Blanqui’s worlds.

1. Proven Future

The film arts still require specific spaces and tools, ever more numerous, miniaturised and intrusive, with which living beings rig out any object and increasingly rig out themselves.

Nothing escapes identification or control any more.

Whether to supervise real gestures or tame the imagination, film apparatuses prove to be the best allies of a totalitarian world, more powerful than any lethal weapon.

A few scattered resistance fighters around the world are determined to make beautiful films worthy of Arthur Rimbaud or Stéphane Mallarmé.

ARCHEOLOGY

– The “Bertillon system”, or criminal anthropometry.

– Hildebrands Deutscher Kakao, Verbesserte Röntgenstrahlen im Jahre 2000 [Improved X-Rays in the Year 2000], 1900.

![(17) Hilbrands Deutscher Kakao, Verbesserte Röntgenstrahlen im Jahre 2000 [Improved X-Rays in the Year 2000], 1900 (17) Hilbrands Deutscher Kakao, Verbesserte Röntgenstrahlen im Jahre 2000 [Improved X-Rays in the Year 2000], 1900](/sites/default/files/16.%202000-imagine-en-1900-Rayonnement.jpg)

Hilbrands Deutscher Kakao, Verbesserte Röntgenstrahlen im Jahre 2000 [Improved X-Rays in the Year 2000], 1900

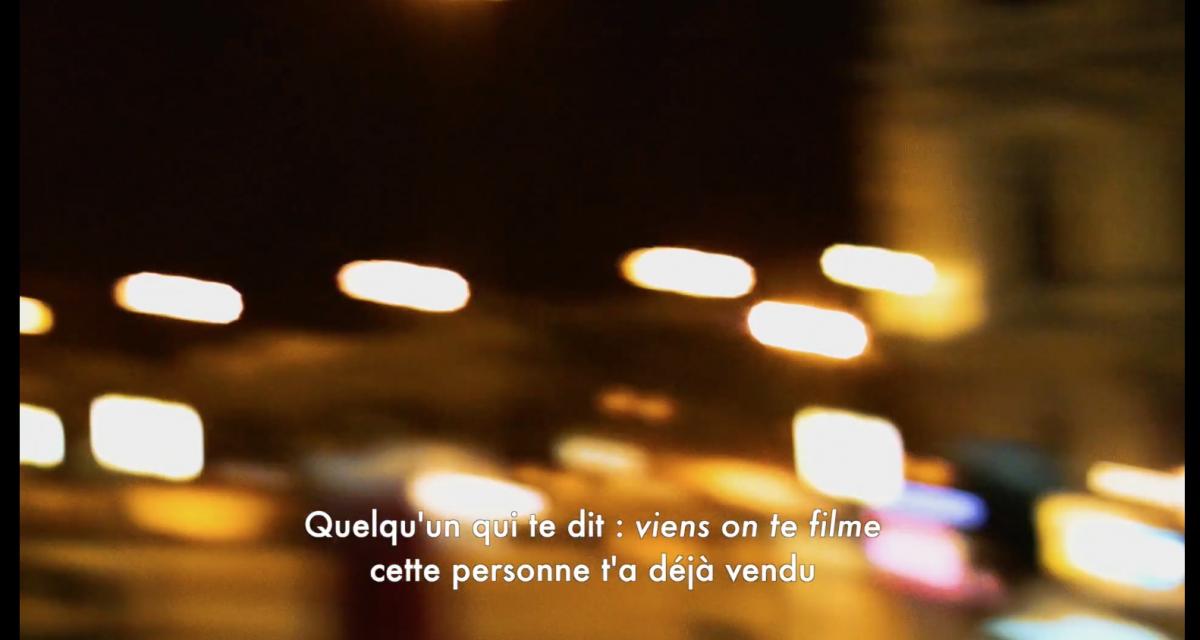

CONTEMPORARY PROLEPSES

We borrow this term from the filmmaker and theorist Edouard de Laurot: by “proleptic cinema”, de Laurot meant cinema that, in the present, seeks and cultivates the seeds of a fairer future. Mostafa Derkaoui, among others, developed a similar conception in About Some Meaningless Events (1974).

Mostafa Derkaoui, About Some Meaningless Events, Morocco, 1974

Clarisse Hahn, Our Body is a Weapon – PRISONS, France, 2011

Bani Khoshnoudi, The Silent Majority Speaks, Iran, 2010

2. Likely Future

No more human crews for creating films. Devices installed in public or private spaces, capable of creating images of all formats and forms, are operational all the time, without scripts or with scripts generated by algorithm-fed A.I. But these algorithms have only been fed by the revolting gruel dumped by industrial platforms.

All over the world, sometimes gathered around the remains of cinematheques or ruins of old cinemas, a few resistance groups are preserving the memory of the arts and still producing counterhistories, sometimes even by speaking to each other beforehand. However lucid and anti-authoritarian their films, the totalitarian states do not consider them any more dangerous than mass-produced amulets of wacky cults. The filmmakers know this, but they film to pass on as much information, dreams and loving signs to later generations as possible.

ARCHEOLOGY

– The force-feeding of geese in South West France.

– Holger Meins, Ulrike Meinhof, Nagisa Oshima, Koji Wakamatsu, Masao Adachi, Aloysio Raulino, Alan Clarke, Peter Watkins, Sidney Sokhona (non-exhaustive list)

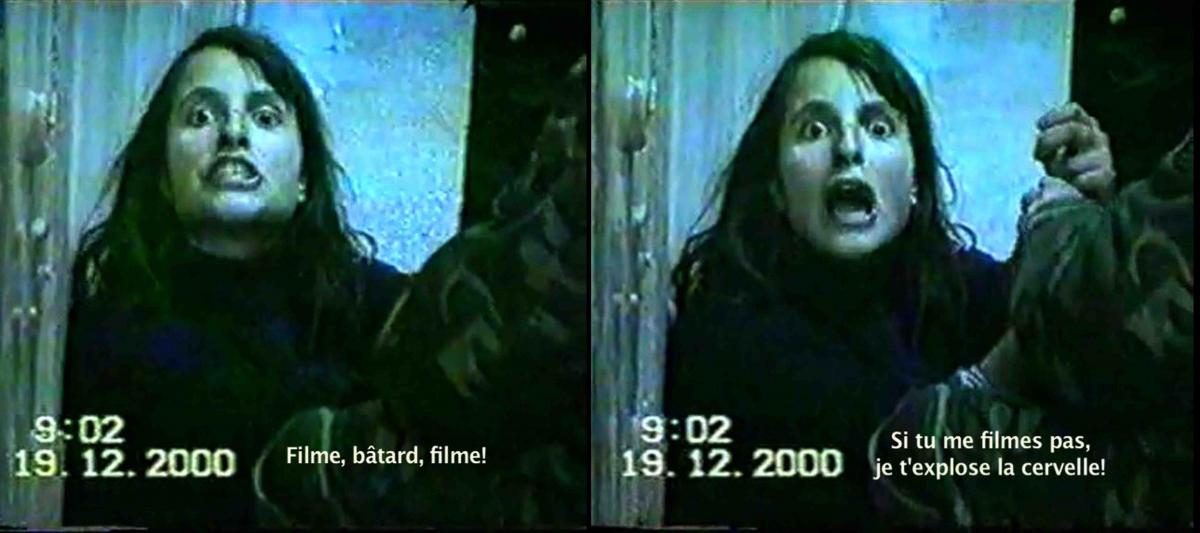

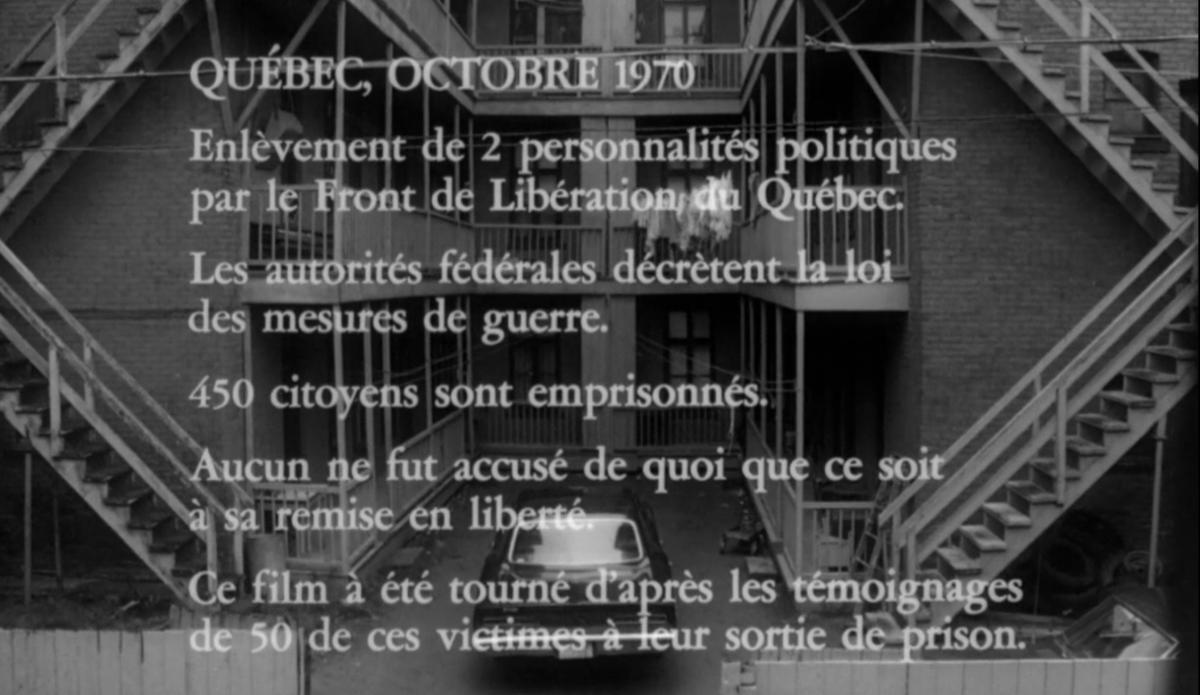

Michel Brault, Orders, Canada, 1975

Ken Brown, Home Movies, USA, 1985 (drawing)

CONTEMPORARY PROLEPSES

Rashid Masharawi, A Ticket to Jerusalem, Palestina, 2002

Hu Jie, Propaganda Images of the Cultural Revolution, China, 2014

3. Possible Future

No more tools to create films. Nanochips are implanted in the optic nerves of living beings, sending them unlimited doses of images and sounds. Art schools are integrated into medical academies and hospitals, where one is taught the dosage of images. Antonin Artaud’s texts on the subject of cinema are no longer regarded as ramblings but as manuals.

Many resistance fighters have refused the implantation, gone underground and continue to create images and sounds with ancient instruments, preserved or created from scratch.

ARCHEOLOGY

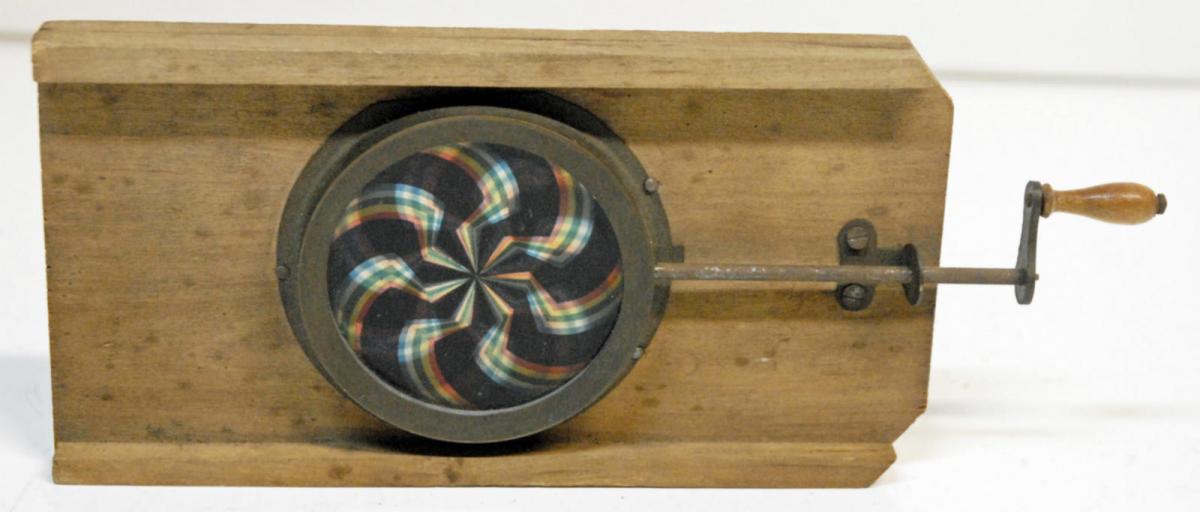

– Chromatrope, 1860.

– Émile Cohl, Les lunettes féériques, France, 1909.

– Ossama Mohammed, Khutwa Khutwa, Syria, 1978.

– Robert Kramer, Ghosts of Electricity, France-Switzerland, 1997.

Chromatrope, 1860

CONTEMPORARY PROLEPSES

Nicolas Klotz and Elisabeth Perceval, Let’s Say Revolution, France, 2021

4. Desired Future

We stop thinking of cinema in terms of tools and commerce. We return to content, to the issues at stake, we pay the same attention to films as we do to frescoes or to the tiniest flower woven into the tapestries of The Lady and the Unicorn. Any chain of moving images is considered a film, and any unchaining of meaning is considered a major event. The spectrum of forms continues to expand, and suddenly cinema proves to be as rich formally as poetry, music, the biosphere.

Sometimes, before creating an image, filmmakers feel the need to reread Heraclitus, Hesiod, Flora Tristan, James Joyce, The Pisan Cantos or F. J. Ossang.

ARCHEOLOGY

– Bruno Corra, The Rainbow and The Dance, painted films, 1912.

– Blaise Cendrars, La fin du monde filmée par l’Ange N.-D., Éditions de la Sirène, illustrations by Fernand Léger, 1919.

Blaise Cendrars, La fin du monde filmée par l’Ange N.-D., Éditions de la Sirène, illustrations by Fernand Léger, 1919

CONTEMPORARY PROLEPSES

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Plages, France-Brazil, 2001

Ange Leccia, Perfect Day, France, 2007

5. Loose Future

The world becomes a permanent festive explosion of colours, sounds, material and immaterial images. At every street corner, on every fallow field, one can have fun sculpting aggregations of mobile images the way sounds are sculpted with a theremin. Our psyches and pockets are overflowing with icons and sounds we can play with at any time, alone or together. The stained glass windows of cathedrals and their reinterpretations by Stan Brakhage or Téo Hernandez are taught in kindergarten. Life has been freed from all quantitative measures and is now only divided up by the course of the sun. No one knows where the “h” in algorithm goes anymore. Mathematics only serves to preserve the living.

ARCHEOLOGY

– Pyrotechnics, China, 2nd century BC

– Ken Kesey’s geodesic dome, USA, 1968.

– Vladimir Vissotsky, Derek Jarman

– José Antonio Sistiaga, Impresiones en la alta atmósfera, Basque Country, 1989.

José Antonio Sistiaga, Impresiones en la alta atmósfera, Basque Country, 1989

CONTEMPORARY PROLEPSES

Karel Doing, Goldenrod, the Netherlands, 2021

For Robert Fenz (1969-2020), Rest In Revolt

- 1This is the transit or occultation method. Like so many other things, this fieldwork is being replaced by A.I. (accessed on 22 November 2021)

- 2At the Ljubljana cinematheque. Jurij Meden, Scratches and glitches. Observations on Preserving and Exhibiting Cinema in the Early 21st Century, Vienna, FilmmuseumSynemaPublikationen, 2021..

- 3See Luc Vialle’s post on sexualities from 15 April 2020, republished on Sabzian, 23 December 2021.

- 4The website of the association that is putting up this fight.

- 5“Ultimately these video and audio samples will accompany the printed or microfilmed version of UbuWeb as a set to be donated to Colorado College, who have offered long-term care of the item as part of their special collections related to the ‘future of the book’.” (accessed on 21 November 2021).

See also Agnès Peller, “Ubuweb de Kenneth Goldsmith, un geste artistique dans les Humanités numériques”, supervised by Nicole Brenez, Paris, la Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2014; and Kenneth Goldsmith, Duchamp Is My Lawyer. The Polemics, Pragmatics, and Poetics of UbuWeb, New York, Columbia University Press, 2020.

- 6Jean Epstein, “Le phénomène littéraire”, in: L’Esprit nouveau 13, 1921. Also in Écrits complets 1917-1923, vol 1, Éditions de l’œil, Paris, 2019.

- 7Fergus Daly, The Mirror of Possible Worlds, 2020.

- 8See Noélie Martin, Ethnographie d’une pratique filmique actuelle : la fabrication des émulsions artisanales, supervised by Patricia Falguières, Paris, EHESS, 2016.

- 9Amos Vogel, Film as a Subversive Art, New York : Random House, 1974.

- 10Interview by Thibault Elie, press file, 2021, republished on Sabzian, 22 December 2021.

- 11Florent Marcie, in: Elie Thibault, Florent Marcie sur le front de l’information : combattre avec le cinéma (unpublished manuscript, to be released).

- 12Ibidem.

Many thanks to all the filmmakers, visual artists and rights holders.

A first version of Part IV was published in: Cecilia Barrionuevo, Marcelo Alderete (eds.), ¿Qué será del cine? Postales para el futuro, Mar del Plata, 2020.

In 2018, by analogy with similar initiatives in other art forms, Sabzian created a new yearly tradition: Sabzian invites a guest to write a State of Cinema and to choose an accompanying film. Once a year, the art of film is held against the light: a speech that challenges cinema, calls it to account, points the way or refuses to define it, puts it to the test and on the line, summons or embraces it, praises or curses it. A plea, a declaration, a manifest, a programme, a testimony, a letter, an apologia or maybe even an indictment. In any case, a call to think about what cinema means, could mean or should mean today.

For the fourth edition on 23 December 2021, Sabzian was honoured to welcome the French film historian, scholar and curator Nicole Brenez. She has chosen Florent Marcie's A.I. at War (2021).