Scope: Format or Ethics

I have nothing to contribute to the technical, organisational and financial aspects of CinemaScope: I know too little about technology and I don’t want to be influenced too strongly by the primacy of economic considerations – otherwise I might as well stop working, that is, thinking. For example, about how innovation comes about in the arts. Even in the arts that are less dependent on the industry, the relationship between technological and utilitarian inventions and artistic expression are more intricate and far-reaching than one generally tends to assume.

Jean Renoir, almost an eyewitness to the emergence of Impressionism, claims that painters were able to “go to their subject” after the invention of tube paints and that this was the beginning of plein-air painting.

To find out what wide-screen is all about, it is helpful to look at directors who filmed in this way before it was commercialised. With Scope, something happened to the cinema images that followed from the movement they contained and from the circumstances of their projection. Which was initially suppressed by the classic academy format. But even before the introduction of Scope, directors who endeavoured to explore the fundamental conditions of their medium tampered with the arbitrary boundaries of the image by expanding them virtually, as it were. Carl Theodor Dreyer, for example, and Renoir, William Wyler and Mizoguchi.

In the spring of 1955, the venerable English film magazine Sight and Sound published the results of a survey among directors on CinemaScope. Jean Renoir pointed out the following:

“Fifteen years ago, everyone who planned to build a house for their old age dreamed of something tall, preferably with a fake Gothic tower on top. Today, the same persons dream of a house with at most two storeys and windows that aren’t high but wide. The I-shaped bonnet of their cars has been replaced by one that looks like a laughing mouth showing all its teeth. Our contemporaries see things horizontally, the generation before them saw everything vertically. There’s nothing you or I can do about that.”

A relief: perhaps taste, before it becomes a fashion and then the norm, is not so externally determined. And German television, which is beginning to adjust to 16:9, its sights set on Europe and because HDTV is not quite there yet, is doing the hardware industry a favour but may be hoping for a different audience than the very large audience that was satisfied with their little TV and its programmes.

In the debate on Scope, from its emergence in the early 1950s until today, the formats and frames of painting are repeatedly invoked as an example – but it is always classical painting, including classical modern painting.

![(2) Pauline à la plage (Eric Rohmer, 1983) [1.33:1 version] (2) Pauline à la plage (Eric Rohmer, 1983) [1.33:1 version]](/sites/default/files/vlcsnap-2020-01-20-14h36m05s739.png)

![(3) Pauline à la plage (Eric Rohmer, 1983) [1.66:1 version] (3) Pauline à la plage (Eric Rohmer, 1983) [1.66:1 version]](/sites/default/files/Pauline_166.jpg)

Nestor Almendros was Eric Rohmer’s cameraman in seven of his films. Rohmer has been in favour of the Academy format 1.33:1 ever since he started making films himself, after he designated the Christian method, as he called it, in 1954 as the only true avant-garde cinema of the time, and Almendros was in favour of the moderate wide-screen format 1.66:1, which he defends by referring to the golden section. Only once did he manage to convince Rohmer of his preference, through the trick of framing Pauline à la plage for both formats. Almendros argues that 1.33:1 is a lazy compromise of the available painting formats for either portraits or landscapes.

From the outset, CinemaScope did not primarily raise the question of image boundaries for Rohmer. The decisive factor was that it changed the viewing conditions. For him, it meant openness, more air, more space for movement, which seemed to him to be enhanced even more by the emergence of colour film at the time. When he defends the Academy format today, preferring grainy 16mm colour film to slick 35mm gloss, it is based on the same motives and fundamentally unchanging idea of cinema: he was and is against the beautiful image, against standardised images that no longer stimulate seeing.

There is no lack of practical, common-sense reasons why Fox pushed its wide-screen approach in the early 1950s by resorting to an invention from the 1930s. But there are also considerations from the realm of painting, specifically American painting, that give a more general purport to what in the context of film merely looks like a matter of cinema formats and screen ratios. At the beginning of the 1950s, a different understanding of the image, a reorientation of seeing was emerging, for example in Rauschenberg’s work, away from the vertical determined by the upright human figure, towards artefacts that neither depict nature nor simulate image depth. We know of de Kooning that he repeatedly watched Giant by George Stevens, whose appeal for him was certainly not the heartfelt family tragedy.

Giant, from 1956, was not shot in CinemaScope. But its image compositions tend towards it. Remember the famous shot that became a cult image of the 1950s: James Dean, in the very front of the image, stretched out in an open-topped car, his feet on the steering wheel. His cowboy hat on one side and his boots on the other form the image’s horizontal boundary. The vertical is meaningless. The architecture, the mansion of the large landowners, is desolately in the back, a miniature dummy. It no longer creates a perspective.

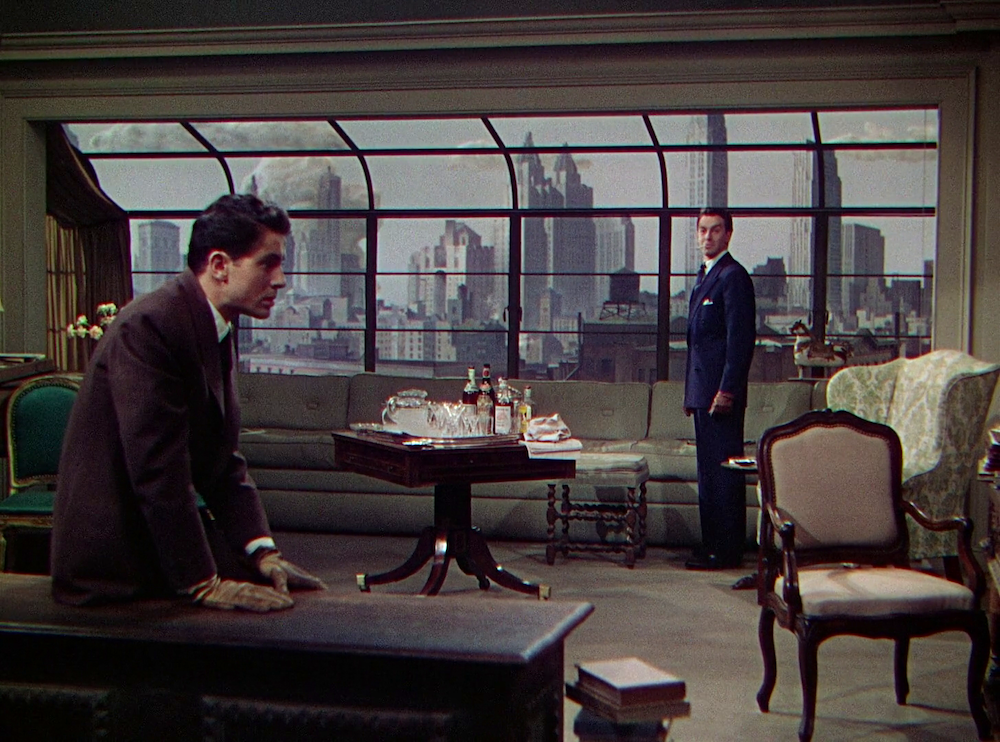

Very early on, André Bazin was surprised to discover that the new CinemaScope format, which was so much in keeping with his idea of more reality in cinema, did not necessarily prove its value in westerns, in wide spaces, but rather in what he called “psychological films”. East of Eden, for example, or the films of Nicholas Ray, which are always bigger than life and approach the new format in a rather hysterical, theatrical way – he has a background in The Group Theatre in New York.

Ray referred to American architecture’s decisive influence on his idea of the image, to Frank Lloyd Wright’s way of perceiving things: “I dreamed of destroying the rectangular boundary of the image, a formal principle that is intolerable to me; I love CinemaScope because I love the horizontal line, which is so crucial in Wright’s work.” At Wright’s academy in Taliesin, Wisconsin, Ray did not study architecture, however, but made theatre at the accompanying playhouse. On its first floor was a movie theatre with 35mm projection and seats arranged in a curved shape “because you weren’t supposed to look straight at the screen”.

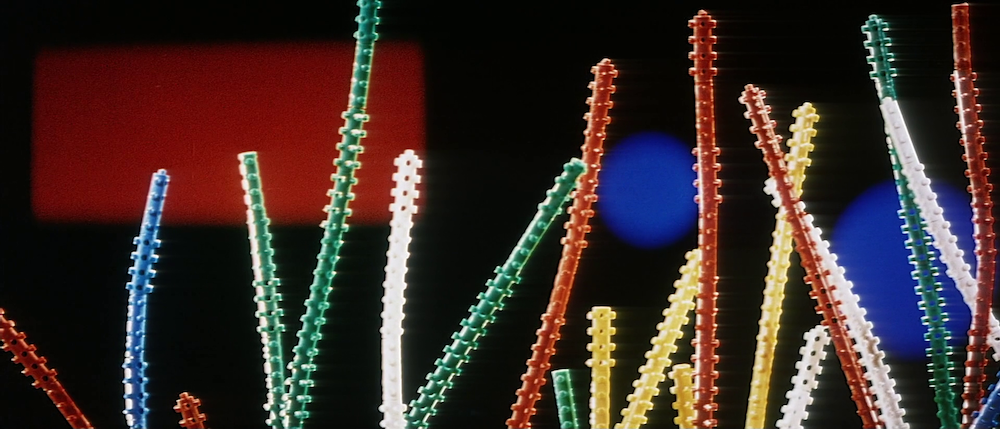

Thirty years after silent film, the wide screen signalled a return to the scenic space in which you could show several people talking at the same time – the rectangular screen forced you take a distance from the actors if you wanted to show them in full size, making it impossible to show the emotion on their faces as well. CinemaScope was the perfect cinema format for sound films. Alain Resnais demonstrated how well it fitted a rolling, sweeping language in The Song of Styrene, in which he combined Dyaliscope images with a text in alexandrines to demonstrate that, in its own way, plastic is also a noble material. The complicated chemical transformation processes were communicated more intelligibly in lofty poetic language than in utilitarian everyday speech. The client, the Pechiney group, initially had another commentary made in the usual explanatory documentary tone but then realised that the coherence of format, colour and language in Resnais’s version was more convincing.

At stake in the new format is the liberation from the perceptual standards that have governed the visual arts since Renaissance scenography – with its depth-focused vanishing points, terms such as foreground, middle ground and background, centrally positioned person and compositional harmony derived from antiquity.

The best films of the late 1930s and ’40s, Rohmer wrote, were inspired by the spirit of the wide screen – Renoir’s The Rules of the Game, but also Hitchcock’s Rope. Those were films that already carried the potential of CinemaScope.

For Renoir, the wide screen is the natural consequence of the introduction of sound, CinemaScope being finally the adequate sound-film format. In The Rules of the Game, he shows the connection between sound and image format by virtuously sending the camera in search of the sound sources, after one first hears only the sound. This is about continuity of space. In Toni, from 1934, he began to combine the environment and the action by means of panning shots. What would otherwise remain mere scenery he brings into the foreground by moving the camera, thus integrating the characters into the décor. The shot gives way to the scene.

The problem of the wide screen as an aesthetic concept, the new image idea before its actual technological possibility, also occupied Carl Theodor Dreyer after Day of Wrath. And he was forced to remain occupied by it until his last films because, however eager he was to film in CinemaScope, he never got the opportunity. After 1943, he had long, uncut passages in his films, with the express intention of eliminating all effects of perspective. He calls it the method of the gliding close-up or “long-tracking close-up with a wave-like rhythm”: “The camera automatically takes all shot positions in a natural order as it moves along.” Depth and volume disappear in favour of a woodcut-like flatness and Japanese-derived two-dimensionality. Dreyer’s intention to direct the eyes in the cinema in other directions, to make them look at the images as if they were friezes, can even be seen in Gertrud, in the minimal details of his last film, in which the heroine’s pelerine is set with a meandering motif that creates irritating movement when she walks.

When André Bazin saw Day of Wrath in Paris after the end of the war, he noted Dreyer’s unusual procedure: instead of the usual shot-countershot, there were short pans, a nauseating horizontal pendulum movement. Dreyer, like Renoir, considers his method and sequence of images to be more appropriate to the speech situation of cinema. They correspond to a scenic conception of space that is no longer only scenography and whose rhythm results from the combined action or interaction of the flow of speech and the movement of the camera.

![(8) Vredens dag [Days of Wrath] (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1943) (8) Vredens dag [Days of Wrath] (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1943)](/sites/default/files/Dies%20irae.png)

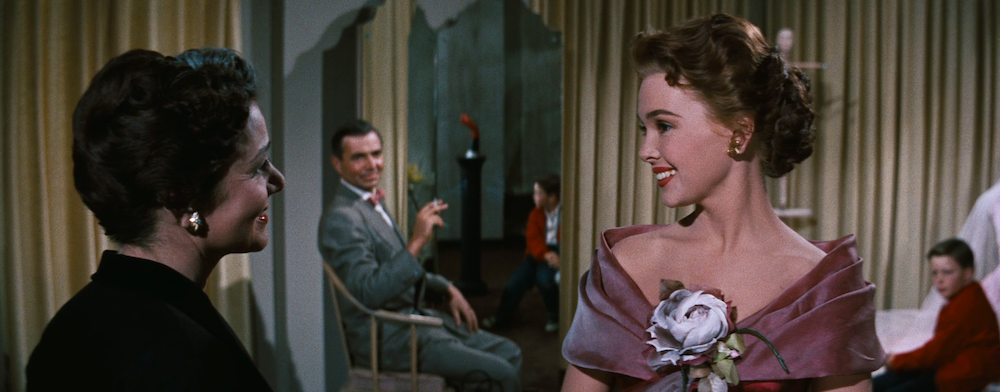

The new linguistic space of the cinema also produces more expansive gestures and new body postures. The wider scene prompted American critics of Otto Preminger’s films to the sarcastic remark that since the mid-1950s Hollywood has increasingly become Broadway. Which also means that, instead of continuing to cater to the masses, which is gradually turning towards television, Hollywood is targeting a middle-class audience who has other habits of cultural consumption. Who now goes to expensive premiere cinemas as it used to go the theatre. An early Fox press release on CinemaScope said that it creates the same form of involvement in the spectators as the spoken theatre with live actors.

The introduction of the new 16:9 television standard could be compared to Zanuck’s reaction when he tried to counter the cinema crisis triggered by television with CinemaScope. The declining number of television viewers heralds a new change in leisure activities. People prefer to play games on their home computers. HDTV is only for audiences with a lot of space anyway. The former mass entertainment, the old films, are now watched at home, privately, in the very best quality.

CinemaScope – and later Panavision – was therefore by no means the better, more expansive genre of spectacle with plenty of room for masses of extras, as was initially assumed, which is why old monumental film strategists like Kertész and Kosterlitz were initially commissioned to produce Bible adaptations. With CinemaScope, Eric Rohmer wrote in his review of Preminger’s The Court Martial of Billy Mitchell, it is not the style that changes, but the ethics. The correspondence between content and image proportions is not of a physical but of a moral nature.

The initial enthusiasm of all the Cahiers writers was rather theoretical. Soon, Eric Rohmer conceded that any method was only as good as the use that was made of it. Since wide-screen became the norm, innovative filmmakers can only seek its destruction.

Based on a lecture held at the symposium on Scope and Super 35 image making, 23–26 November 1995, Dortmund.

Image (1) from La règle du jeu (Jean Renoir, 1939)

Image (2) from Pauline à la plage (Eric Rohmer, 1983) [1.33:1 version]

Image (3) from Pauline à la plage (Eric Rohmer, 1983) [1.66:1 version]

Image (4) from Giant (George Stevens, 1956)

Image (5) from Bigger Than Life (Nicholas Ray, 1956)

Image (6) from Le chant du Styrène (Alain Resnais, 1958)

Image (7) from Rope (Alfred Hitchcock, 1948)

Image (8) from Vredens dag [Days of Wrath] (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1943)

Image (9) from The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell (Otto Preminger, 1955)