Straschek 1963-74, West Berlin

Part 4

The title of the text “Straschek 1963–74 West Berlin” is as simple as it is informative: it is a subjective, self-reflective insight into Günter Peter Straschek’s eleven years in West Berlin. During this time, he was many things: filmmaker, film historian, film theorist, writer, politically active in the protest movement of 1968 and part of the first generation of students at the Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin [German Film and Television Academy Berlin] (DFFB). Straschek’s fellow students included people like Helke Sander, Harun Farocki, Hartmut Bitomsky, Johannes Beringer and Holger Meins. His essay provides unique access to the film-aesthetic and -theoretical debates and practical-political discussions of a generation of filmmakers who were to fundamentally renew filmmaking in Germany, and whose political and formal experiments made the preceding generation of Oberhausen Manifesto filmmakers look staid. Born in Graz on 23 July 1942, Straschek merged his experiences and interests from his West Berlin period into one condensed virtuoso composition for the magazine Filmkritik. Straschek created a constellation of various text types, such as political-theoretical and film-aesthetic reflections, anecdotes, diary-like entries, letters or even feeding instructions for Danièle Huillet’s cat. It is a text montage that most filmmagazine editors today would probably shorten considerably and change formally. The text owes its publication in this form to the spirit of the time, but especially to the editorial guidelines of Filmkritik, which was certainly the most prominent film magazine in the German-speaking world at the time.

– Julian Volz1

59.

Suhrkamp Press

– edition suhrkamp –

Attn. : Mr. Günther Busch

6 Frankfurt am Main

P.B. 2446

Günter Peter Straschek

1 Westberlin 41 Kniephofstraße 12

Tel. 791.63.09

29 May 1974

Dear Mr. Busch:

I informed you a couple of weeks ago that notes on the publication of my Handbook against Cinema (hereinafter HwdK) would be forthcoming in the August issue (which I shall be writing) of the periodical Filmkritik. You took note of this and reserved the right to reply. The present letter to the Suhrkamp publishing company, directed to your attention, presents my complaints. Should your answer reach me by June 14, it could also, with your consent, appear in the August 1974 Filmkritik as a counterpoint.

The ms. of my HwdK was sent to your press in October 1971. To that point, I had received advances on royalties of 4,000 (four thousand) marks. On December 20, 1971, you wrote, in response to me: “Your ms. will be going to the typesetter in January … As to your request concerning the fee, I cannot accommodate it at present. Our accounting department has informed me that the balance of the sum owing to you will become available only after publication of the volume.” In January 1972, I resubmitted a revised version of part of the ms. – in particular, of the concluding chapter, chapter 4. I repeatedly urged you, in letters and telephone conversations, to see to it that HwdK was released rapidly, in view of the extensive editorial apparatus. I do not know whether you have ever read my work; a cursory glance at the ms. would have convinced you of the need to publish it in short order.

It is true that I had already finished the ms.; I had, however, to continue updating it for as long as it was at your press pending publication. This cost me a great deal of work, time and, especially, money. In yours of July 10, 1972, you stated: “We have decided, with promotional considerations in mind, to publish the Handbook in late autumn. This release date seems to us to be more advantageous for the book than a date in late summer.” Your “more advantageous” is fairly cynical, given that your press has not marketed HwdK to the present day; what is more, this kind of scheduling hardly seems to be standard practice for a series such as the “edition suhrkamp.” In the expectation that I would have to make corrections calling for a major expenditure of money and time (as goes without saying, I was already at work on a different project), I again requested that your publishing house grant me a partial advance on royalties of 1,000 (one thousand) marks. This request too was denied.

In the event, the galley proofs did not reach me until January 1973, that is, fifteen months after submission of the ms.! Moreover, half the text was missing, around forty sheets of bibliography and fifty sheets of footnotes; and it was the October version that had been typeset (sloppily at that), not the January 1972 version with my additional corrections. Quotations in Italian, Russian, and Portuguese that I had asked your press to translate had been left in the original languages. On the other hand, not only had your copyeditors “Germanized” my Austriacisms; my view that the student moviegoing audience was, measured against its pretensions, the least thoughtful, comparatively speaking, had been purely and simply struck from the text!

At any rate, over the next year and a half and more, it was again left to me to update the text (the galley proofs) and the editorial apparatus with some eight hundred footnotes (in the manuscript), and also to draw up three indexes. To be able to provide new statistical details, dates of death, and other supplementary information, I had to conduct correspondence with cinematheques throughout the world, and also to travel to the Danske Film museum in København, because the collections in German cinema libraries are inadequate. All costs had to be paid out of my pocket – I had to assume them, despite my strained financial situation, because your publishing firm refused to disburse the funds, while I was unwilling to see the HdwK published with an outdated editorial apparatus and could not simply throw the whole thing over after putting so much work into it.

In July 1973, I returned all the updated material to you, and urgently requested, by letter and in telephone calls, that you produce the page proofs and proceed to publish the book as soon as possible. Nothing of the sort happened.

You should not, let me add, ignore the fact that, in a period in which a few sparse signs of West German interest in books about cinema had appeared, it was not particularly cheering to see the work of “my colleagues” come out before my own as a result of your publishing firm’s quasiboycott. And if it was flattering for me at first to be often asked when my book was finally going to appear, it quickly became annoying to have to answer, literally for years, that I didn’t know. In the end, the whole business became not just embarrassing for me, but also dangerous, because the long wait for the already announced book could only raise expectations, which generally find their simplest resolution in the form of disappointment. Your behavior in this period, or Suhrkamp’s, was more than strange. Not only did I not receive a cent, in spite of an unusual situation for which I bore not the least responsibility; I was ignored even when I ordered Suhrkamp books at the reduced prices granted your authors. HwdK was never again mentioned in the press’s prospectuses, and even went unmentioned in the announcement of books forthcoming in the latter half of 1974. The idea of running an advertisement in Filmkritik was rejected. In June 1972, I wrote to ask whether “edition suhrkamp” might be interested in a biobibliofilmographical cinema lexicon by me (as editorinchief); in July, I inquired about the possibility of publishing a German edition of (Antonio) Labriola. In neither case did you deem my question worthy of a reply. In December 1973, you announced that I was to correct the galleys in January 1974. I planned accordingly, budgeted time, postponed other work – but, once again, things were repeatedly postponed, dragging on until May 1974; that is to say, another ten months after correction of the galleys. And what I finally received wasn’t page proofs, but a second set of galleys – with eighty pages of bibliography this time, but nothing of the text proper. When I called you about that, you said something about “a little mishap.” In other words, in the space of ten months, the editorial apparatus had been typeset, but the handcorrected body of the text itself had once again been forgotten. Let me note in passing that you promised me the galleys of the text proper by a date that is already ten days behind us.

Thus I again find myself confronted – two and a half years after delivering the manuscript – with a fragment. Not only do I once again have to write to or call all the cinematheques, travel to København, and revise the whole book; it is not clear, even today, when it will be possible to publish it, the more so as correction of the page proofs still lies ahead of us.

I of course accuse Suhrkamp of deliberately or negligently delaying publication of my HwdK, something that has resulted in considerable damages for me. I am not, however, angry at you and the publisher alone; I am much angrier at myself for playing the fool. I have, after all, spent two years writing this book (not counting the preparatory work), and subsequently had no choice but to emend all sorts of little slips and update the material while I waited around, simply because your press had left me on hold, and all this for a fee of 4,000 (four thousand) marks – a sum that I had to spend in its entirety on postage, telephone calls, photocopies, and so on. Although you were aware of that and, what is more, although the cover price of HwdK has in the interim risen to twelve or fourteen marks, and, with it, my royalties of seven percent on each copy sold, it never once occurred to Suhrkamp to make me so much as a gesture of financial support.

After enduring all this, I now find the whole business disgusting. I had to cancel a contract with Rowohlt for a study of movie companies; I can hardly afford to waste another couple years writing a complicated chapter of cinema history – for a fee of a couple thousand marks!

If my HwdK should appear on the market in October of this year, exactly three years will have gone by since I delivered the manuscript! I would be very much obliged if you would let me know the reasons for this delay, and your press’s motives toward me. I myself am unable to come up with a convincing explanation for it, since I cannot see what your, or, rather, the press’s interests in such a delay are. Perhaps there were technical problems; typesetting the ms. is admittedly complicated. Acquaintances of mine ascribe political motives to you; I myself do not, since publishers are, after all, making a killing on the leftist book boom, and since, as BB rightly remarked, “in the end, Marxism has become so little known thanks to the many writings about it.” Or was it that you wanted to get even for my late delivery of the ms.? (I have stated my reasons for that in my text for the August 1974 Filmkritik.)

I would be very much obliged if you would respond to my questions and criticisms. I would also ask, in view of the circumstances I have de¬scribed, that you intercede with your press to have 2,000 (two thousand) marks paid into my account with the Berliner Bank, account no. 1113264700.

Best regards,

(Günter Peter Straschek)

60.

Günter Peter Straschek

1000 Westberlin 41

Kniephofstraße 12

Suhrkamp Press

Frankfurt/M., 12 June 1974

Bu/wi

Dear Mr. Straschek,

I shall make it short.

1. In your letter, you state that you sent the ms. to the publisher in October 1971. What was involved was of course not a ms. ready for the typesetter, for you say – I quote – “in January 1972, I re¬sub¬mitted a revised version of part of the ms.” That means that the completed ms. was not in the press’s possession until late January 1972.

A marginal note on the chronology: the contract between you and the Suhrkamp publishing company bears the date of May 22, 1969. The agreement was that the ms. would be in the press’s hands by August 1, 1970. (I cannot, incidentally, remember ever having confronted you with a legalistic interpretation of the situation.) So much for a reconstruction of the facts of the matter.

2. You yourself admit that your ms. puts unusually high demands on the compositor. Anyone who does not take this sufficiently into account will also underestimate the problems that technical production of the Handbook involves.

3. The printer’s work schedule is geared to our publication program for the following six-month period. Work can be done on titles that have reached the press after a significant delay only as ongoing production, which has priority, allows. There is, be it added, no lack of other instances in which publication of volumes in the series “edition suhrkamp” was delayed for the same reasons as in the case of the Handbook.

4. Your remark that the student moviegoing audience is “the least thoughtful, comparatively speaking” contains, as you yourself know, a blanket judgment that you make no attempt to prove or explain in your text. But a countercliché too remains a cliché.

5. It only makes sense to discuss promotion of the Handbook in connection with the publication date. The same holds for the corresponding references in our prospectus. I have repeatedly explained that to you.

6. The idea that political motives have played a role in this affair – an interpretation that you do not share, it is true, but that you nevertheless repeat after others – is one which only those unfamiliar with either the “edition suhrkamp” or your ms. (or both) could entertain.

Nothing of what I have said to you here about this matter is new to you; it cannot be. Over the past months, I have repeatedly presented you with reasons and explanations. I would prefer that our working relationship not be entirely skewed by emotionality.

Yours sincerely,

(Günther Busch)

P.S. I shall try to arrange another advance on fees.

61.

[Okay. I dispense with a response and emotionality, because, on June 15, 1974 – for the first time – all the galley proofs of my ms. reached me. It can now be presumed that Handbook against Cinema will appear in October. As for the Rowohlt press, I offered it the movie industry emigrants in lieu of the movie companies. But it simply wasn’t interested. After I had insulted the acquisitions department by airing the view that it should stop making such a fuss, that it was ultimately a matter of perfect indifference whether movie companies or film industry emigrants were sold in the collection “das neue buch” [the new book], the best of all possible solutions was found: I am to return 4,000 marks of my 5,000mark advance, and neither the movie companies nor the emigrants are to see the light.]

62.

Passionate music lover. I have downright styled myself a Schubert fan – the string quintet in C major, the piano trio in Eflat major, or the great piano sonata in B major are, in my opinion, magnificent works. I’m by no means embarrassed about continuing to enjoy music (about which I haven’t the least notion) as a naïve art experience. Because my various media knowledge of literature, cinema, theater, or television no longer allows me to enjoy the corresponding massmarket art forms. I nevertheless believe that, of all the traditional art forms, music is, by its nature, the one most closely akin to cinema.

63.

The incident occurred in a London Hotel near Lancaster Gate, on the nexttolast day of shooting for Part 1 (“Europe”) of the film about filmindustry emigration. In the breakfast room, the staff of immigrant Spaniards had more work than it could handle. That was, to be sure, not particularly pleasant for us; but our head cameraman, who, like most West German TVtypes when they’re abroad, had his head stuffed full of the arrogant idea that all he was supposed to be doing was eating and fucking, had to go and lodge a complaint. When he came back, he found a tray on his seat that the waiter had deposited there. Angrily, he hurled it into a corner of the room. That enraged the waiter. He crept up behind my cameraman and yanked him up by an ear, as if the fellow were a naughty schoolboy. What happened next was slapstick. The cameraman bellowed in showoffish Oxford English, “Don’t touch me!” while the Spaniard came out with “You stupid man!” Then each went at the other. Because we had to shoot in a club at 10 o’clock, I separated the two of them after a while. Clutching their necks with outstretched arms, I held them apart. The cameraman was trembling with rage and white as chalk: a pair of Scandinavian tourists sitting at the next table over had to restrain him. The Spaniard prepared to let fly with a coffee cup. After that, he tried spitting; since he was nice enough not to want to spit at me, he spat in an artistic arc over my head, successfully attaining his target, Werner D. The latter had ruined a good part of my film with his lousy camerawork, but, for a fraction of a second, I felt sorry for him. What terrible times must these be for a reactionary, when a fortythreeyearold cameraman with a permanent job at the WDR can be dressed down by a Spanish breakfast waiter in a London hotel …

64.

Women’s effort to achieve emancipation seems to me to be one of the most complicated forms of warfare on several fronts at the same time. It is beyond question for me that it represents a decline in men’s power (which might well lead to the conclusion that the zealous gentlemen who go on endlessly in defense of women’s liberation aren’t quite kosher, or are hiding their hand and up to no good). Things get fuzzier when one tries to conceive of liberation as a new quality. Today there really is no lack of women who are quite happy to be able to engage in the same sort of idiocy as men. But what is at issue here is “better,” not “more equal.” Not much can be done with that misunderstood quotation from Engels – in view of “women’s” mind-numbing capacity to show each other no solidarity at all. A cultural revolutionary cleanup among the feminine rankandfile is, in any case, badly needed: in the film sector, for example, the number of hysterical females who are full of themselves is an embarrassment for the “professionally active woman.” I myself have a solid reputation among feminists as a “misogynist.”

65.

A tremendous interest in modern history, or what should perhaps be called interest in the competition. It’s only in the past few years that I’ve stumbled upon the field of military history and the history of warfare and chosen the relationship between Marxism and armed conflict as a field of specialization. Even here, certain roots go back to my childhood: I was brought up by my parents in an antiNazi spirit, and that was bound up with a powerful aversion to the military and uniforms. Naturally, I was a pacifist, although I never got as far as formal conscientious objection because I’d left Austria beforehand (that was one of the reasons I left). It was the Außerparlamentarische Opposition [ExtraParliamentary Opposition] that brought me round to new ways of looking at things: to the view that certain areas are traditionally dominated by the enemy only because we would ideally like to deny their existence. Moral condemnation shouldn’t be allowed to become a factor; necessary knowledge of the strategy of the anticlass struggle should. While arriving at this insight, I discovered a curious left predilection for glorifying our defeats. Is it not more urgent, rather than perpetually underscoring the International Brigades’ bravery, to take note, for once, of the weaknesses of the Left in defining its strategy, arming its forces, stocking up on supplies, etc., and of the Soviet Union’s mistaken decisions – and to learn from them? (Even as a teenager, I was irritated by the fact that, in films about revolution set in Mexico, peasants were mowed down like flies by machine guns as they stormed the presidential palace. Couldn’t that have been done better, with fewer casualties?) I’ve never for a second doubted that socialism will triumph. The question is when and how. In the day-to-day struggle, teleological hope in the form of an eschatological confession of faith isn’t without its dangers. Furthermore, my readings in Marx and Engels, as well as the study of the sources that I’ve carried out so far, have shown me that the Left was anything but pacifistic in the nineteenth century. Only in the revisionist phase did pacifistic defeatism carry the day, and this was partially to blame for the string of defeats between 1918 and the Second World War. Whether in Spain, Indonesia (the most appalling mass slaughter since Hitler), or – as is to be feared – in Chile: when the reaction succeeds in physically crushing working-class cadres in a putsch/civil war, it seems that it is wellnigh impossible to make good the defeat for decades to come. No one should behave like a Red weepingwoman; rather, what should be insistently promoted is generalstaff work and ongoing analysis of the many defeats (of the German working class in the face of Nazism) that are still incomprehensible for many (and, ultimately, for me too).

[Personal balance: however passionate and aggressive a human being I may be, I’m as emotionless as I can be (and already was as an SDS member) when confronting the reactions of the state and those who hold equity in it. The reaction is, precisely, a reaction; almost nothing can be achieved by means of indignation. It would contradict my tactical principles to rebel in hopeless situations instead of staying cool to save my strength. When I was once briefly in jail, I neither bombarded the cops with appeals to convert in the “we really aren’t at all like that, and you’re different too” mode, nor were they swinish scum in my eyes. (I take the liberty of noting that anyone acquainted with the police state known as Paris, or with Italian, to say nothing of American, cops, can only consider ours to be relatively “tame”). The cops were, rather, typically anonymous lackeys from the lower orders, and I was only able to steer clear of them in this situation by remaining calm and reserved. Grandstand gestures on our part after defeats, as well as unnecessary victims, should always be rejected or avoided. We’re not in the Boy Scouts, after all.]

66.

A city of squares. On every one of my annual visits to Rome, I find the Piazza Farnese or the Piazza di Santa Maria in Trastevere to be as magnificent as ever, and the same holds for less spectacular squares such as the Piazza di San Salvatore in Lauro, not to mention the Piazza del Catalone. It was, in any case, cold as a witch’s tit in the movie theater (the 1973 energy crisis) and boring besides; but when Helmut Berger clambered over the bed Edwardgeerobinsonstyle, I said to JeanMarie S. that Romy Schneider was the only decent actress in this Viscontioperetta. “Did you know she wanted to do a film with me?” I thought to myself, “Now he’s joking.” “Not at all. She wrote a letter to Delahaye to say she’d seen Not Reconciled and would be happy to be able to make a movie with me. That was right after Not Reconciled; we hadn’t directed anything else yet.” I added that, for me, Romy had always been a decent actress who was generally underestimated because she was unpopular. JeanMarie S.: “I like that girl!”

67.

In November 1973, after eight weeks of shooting, we were driving through Belgium headed for Cologne and its WDR, stepping on the gas because we were homesick. Soundman and production manager started gushing. Those were the days, way back when in Berlin, on the other side of the border! We’d change money every weekend at the “Zoo” train station, at a rate of four marks to one (at least), and then make straight for the border. For a couple of westmarks, you could eat yourself sick and fuck your heart out; a fiver got you the farmer’s perfect daughter fresh off the farm; for pocket money, she’d give you a blow job. And then the deals we used to make! … [From the word go, I’ve had an understanding attitude toward the Wall and, necessarily, for the order to shoot, since, otherwise, anyone with a ladder could have clambered over to the other side. What’s more, I don’t find the idea of Germans shooting at Germans any worse than that of Germans shooting at foreigners. Besides, everyone is tacitly happy about the fact that the Krauts are divided and so have to leave the rest of the world more or less in peace for a change.]

68.

To tell the truth, I’m struck by the fact that I don’t stand a chance when it comes to TV dramas. Switzerland and Austria (where the entertainment department is headed by the cryptoNazi Kuno K., disguised as a Freemason) are in any case out of the question; but if you aren’t accepted at the WDR, NDR, Bavaria, or the ZDF because of your conception of cinema, and face accusations of “personally motivated” boorishness besides, you can go emptyhanded for years. A handful of bosses and a couple of purchasing agencies. Offer TV something and hope it will cooperate: okay. Or you’re commissioned by TV to do a Gaboriau, for example. Also okay, and almost better. Ever since my synopsis of “Those of Goodwill: A Portrayal of Customs” was vehemently rejected everywhere, TV doesn’t even consider my proposals, which are turned down with cookiecutter letters. This leads me to suspect that a few script editors have understood something of this project and drawn a few parallels. The story line: entrepreneurs in West Germany hire leftist intellectuals to carry out a special mission – exposing failings and dirty tricks in our society. Then they invest in “social change.” Concrete example: construction of a Hilton Hotel reserved for immigrant workers in West Berlin. Progressive sorts discover the trap they’ve been lured into too late. They’re left with a few private solutions. Structure and style: sequences in geometrical progression, puppets as characters, artifice. The response of the producer of “Alfred,” the WDR’s Peter M., in a letter dated June 1, 1973: “We feel that this movie is contrived; it pays no attention to its characters and runs them through their numbers like abstract, lifeless marionettes who are therefore – as I see it – inhuman … I’ve stated the matter this bluntly and impolitely because I think such candor is indispensable if we’re to continue to try to work together.”

Reclam’s Guide to Correspondence. In a letter dated January 13, 1972, the union boss Werner K., started out with the rejection: “Dear Mr. Straschek, I would like to state the conclusion of my letter beforehand: I see no chance of success for your project, ‘The Collegno Amnesiac,’ at Bavaria” (after he’d familiarized himself with my movies), and ended on a conciliatory note: “The quality of your films consists, among other things, in the fact that certain aesthetic problems aren’t so much as broached: you simply take up what is simplest and closest to hand. It will occur to one who knows how to interpret this properly to level the charge of dilettantism that you feared. It so happens that I saw, a few minutes before your movie, one of those unutterably unimaginative television movies in the problemfilm genre. The sheer inanity of the takes in this movie is aesthetic dilettantism. Your purism stems from careful consideration; it is easy to see that it is an expression not of conceptual poverty, but of passion. Aesthetic professionalism, however, is a poor selling point, and no selling point at all with the only possible financial backer in this case, the WDR, which now even balks at Straub. I shall spare both of us the remark that I am deeply sorry about this.” Dieter M. of the NDR about my synopsis of “Those of Goodwill: A Portrayal of Customs,” in a June 26, 1973, letter that begins “Dear Mr. Straschek, I have left you waiting for a long time, but can inform you of no better decision: unfortunately, no”; follows up with a bit of praise: “but I was astounded by what is obviously a profound misunderstanding of your text. For precisely what he [Werner K.] belittles as ‘schematism’ seemed to us to be – how shall I put it – almost Sternheimian quality. The stringency of the images makes sense to us”; and ends with insulting sentimentality: “you may, however, be sure of one thing – if we had found your text less relevant, I would not have hesitated as long as I did before sending you this reply.” That is why I would like to make the personal acquaintance, before I die, of the ZDF’s Mr. Hermann Meier. Whereas, in the case of Werner K. and the WDR’s TVdrama department, differences at least surfaced, and whereas other TV stations (such as the HR) took the view that my plots, “too remote and exclusive for the broad general public of a mass medium such as television,” called for “a correspondingly educated and, as it were, elitist public, of the kind that we unfortunately do not have in television” (I have indeed failed to find such a public “in” television), Mr. Meier is a ghost. When I send him something, he responds forthwith, informing me of the number assigned to my synopsis in Mainz. Three months later, he must unfortunately inform me that the “material cannot be integrated into [the station’s] programming.” A more personal approach did make itself felt in a letter dated December 14, 1973; in a chummier tone, I was told that my “story failed to convince” at the ZDF.

One more example. With Uwe G., I write a “detective story” synopsis titled “Not Bad, Theoretically Speaking.” A married couple pulls off a coup, but, trying to avoid the compulsory mistake after getting its hands on the loot, lends the money to an entrepreneur for three years at interest and thus manages to avoid giving anyone grounds for suspicion. At the end of the prescribed period, the old boy refuses to shell out the lucre. A silent struggle ensues. The husband wants to fight to recover the haul; the wife coolly suggests that they pull off a still bigger coup – in the field of computer crime …

On October 30, 1973, I send the synopsis from London to a few television stations. In a short two months, it’s turned down on all sides; not a word is said about the subject matter or possible modifications. Only the NDR fails to reply. On February 15, 1974, I request that Dieter M. respond to my letter, should the occasion offer. On May 1, 1974, I apply to him again, requesting that he at least send the synopsis back. A few days later, a script editor from the televisionmovie department calls me and, repeatedly begging my pardon, informs me that parts of my synopsis have been lost, that time went by while he looked for them, and so on and so forth. I ask whether the scenario stands a chance. Answer: none whatsoever; the NDR has no money. I thereupon politely request that the gentleman refrain from using these hackneyed excuses in my case: I’ve been hearing them for years, I say; it is obvious that movies will continue to be produced (if, admittedly, on a limited basis) and, I add, there surely exist criteria for determining what can and can’t be produced. All I ask for is an editorial team that, instead of shaking me off as if I were an old lady penning Sunday school verse, takes the trouble + has the courage to explain to me the whys and wherefores of the decision to reject my work, or what alterations seem desirable. The script editor answers that skeleton summaries of screenplays no longer stand any chance of success / everyone knows that there is a shortage of good television writers / no funds for commissioned work. I’m aware of that, I say, but TV can’t reasonably expect me to invest the time needed to write out a screenplay (apart from the fact that I consider it wrong to do so, because a television screenplay should only be written when the author has at least a rough idea of the total available budget) that will eventually be subject to the department head’s decision about whether I receive payment of approximately fifteen thousand marks or, after working away for perhaps nine months, have to come up with the third-class postage on top of everything else. Even when all that’s involved is a skeleton synopsis, the disproportion between the investment in time and effort and one’s chance of success is crippling. TV, I tell the script editor, ought therefore to sign contracts with its authors. If I ever make the trip to Hamburg, the script editor tells me, he and I can discuss the matter over a beer. I ask whether, in that case, the NDR would pay for my beer. No, says the script editor.

I’m to blame. I work too long on stories, and then I send the nth, highly condensed synopsis to TV, without doing the necessary lobby work – and get pissed off when the script department shows no understanding of it and isn’t even ready to enter into a discussion. I obviously ought to produce very different sorts of films, and produce them in a team that, for starters, throws in a woman for good measure. A theme with plenty of pedagogical humbug and “emancipation” (a pretty young heroine leaves a very dumb advertising exec, belatedly earns her secondary school degree in adult evening classes and is profoundly politicized thanks to her fouryearold son’s progressive play group).* The whole thing in tearjerker mode with long takes, preferably of riding down the road in a car. Obviously, we’d shoot on original locations; it looks like reality but, in reality, costs much less than shooting in a studio. I see Eva Mattes or Hanna Schygulla in the leading role, backed up, on the RainerWernerF.method, by an old trouper from the 50s (they come considerably cheaper these days). Dialogue in dialect wouldn’t be a bad idea, and the word “fuck” would have to be used in the movie theater version. The background music for all this rubbish: beat or pop – I really don’t know the first thing about either – which would crescendo during the long rides down the road. Finally, the most important part: the issues, politics. So that the gentlemen in the script department in Cologne, Munich, and elsewhere don’t have to think too hard – they’re responsible for an audience millions strong, remember, not for an elite – sentences such as “society is to blame for everything,” “we see a reflection of the relations of production in that,” and “the capitalist system is only out to make a profit” should all occur twice. At the same time, because this mustn’t stick out, I recommend another trick here too: the old concept of destiny should be replaced by the new concept of society. As for the style of the rest, the good old BavariaTV style has proven its merits.

* The sequel, i.e., what she does next, would truly interest me. Apropos: I don’t have health insurance. So far, I’ve only come down with the clap a couple times, but if something more serious should …

69.

Bedtime treat, 1974: reading Jay Robert Nash, Bloodletters and Badmen: A Narrative Encyclopedia of American Criminals from the Pilgrims to the Present, published by M. Evans and Company, Inc., New York, and distributed in association with J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia and New York, 1973.

70.

Making movies is, for me, just one means of expressing myself. The idea of blustering my way around this trade to the end of my days (in line with the TVformula: regular staff editor marries secretary while secretly supporting film editor girlfriend) scares me. If, for example, I really stood no chance of making films for TV, I would move to another country or work in an institute or publish a book or go off somewhere for a couple of years and do manual work or take a civil service job. I’d like to live in as unalienated a way as possible; things are awful enough as they are. It’s true I’m already thirty-two, but in the coming thirty or forty years, in which I’ll have to work to be able to live, I’d like to do enjoyable work on problems whose solutions I can, with other colleagues, turn to political advantage. Let me expressly emphasize how important pleasure and satisfaction in my work are for me; I couldn’t make a good factory worker for the rest of my life any more than I could make a “progressive” schoolteacher – and for as long as the party doesn’t require me to do anything of the sort, I won’t. With that, I acknowledge my special status, and intend to take advantage of it to the extent that I can without impairing the interests of the proletariat. People have accused me of cynicism in this regard as well, but the accusation was more an expression of their own envy and insincerity. I’ve known too many colleagues who, in their midtwenties, when they were still getting an education, were on the radical Left, but turned into reactionaries when they started in on their careers in their mid-thirties – discovering and exploiting their privileges only at that stage. I’m training for the long haul.

71.

Daily routine: 8:30 a.m., breakfast and the newspaper. The current main project until noon (at present, movie industry emigration). A selfprepared lunch. A midday nap & music, or a cafe and a stroll. Work on one or two parallel projects until evening (at present, socialism and violence/the military), winding down into less strenuous activity (bibliography, correspondence, etc.). Then dinner out and movies/TV or a pub, not by myself, if possible. One library day per week. In London, I want to go on bicycle trips to the countryside.

72.

I share JeanMarie S.’s and Danièle H.’s opinion that, should a revolutionary situation materialize in Western Europe, radical leftist intellectuals would, for reasons of security, have to be taken into custody for a month or two – for the sake of success. These radical leftist intellectuals are a risk because they’re extremely unpractical, and try to make up for it by doing nothing but passing resolutions and theorizing every which way. They can and ought to be put to cautious use after the victory, but should be put out of harm’s way during the armed conflict. They can’t hold a rifle, haven’t the foggiest notion of technology, and lack all practical experience; they would just stand around or write pamphlets. A glance at the history of the socialist movement in various countries shows that there is nothing monstrous about this suggestion.

73.

The WDR has paid me for my work on emigration in the film industry (the obligatory 7,000 marks for forty-five minutes of third-network programming) = my first year of eating regularly. I’ve already put seventeen pounds (some of it in the form of a paunch) on my already rather unattractive exterior. Who would have expected that of television.

74.

Our socialist film work could start moving forward again if we admitted to ourselves forthwith that our methodological approach has failed; if we overcame our fragmentation and unified, drew up balance sheets and classified our mistakes. A point I suggest putting on the agenda: that we talk more about money and how to drum it up. Moratorium on theory.

75.

What I’ve lived on all this time:

From 1961 to 1963, on all the “miracles” you experience only on the road (being treated to meals, etc.) or on donating blood. On the kibbutz Giv’at Hayim Me’uhad, I picked oranges and dragged irrigation pipes around; in Paris’s central food markets, I swiped fruit; for eight months and more, I polished silverware in Amsterdam’s Hilton Hotel. My dear mother would (often without my father’s knowledge) slip a five dollar or ten dollar bill in the letters she sent me.

In West Berlin, I had an extraordinarily tough time of it until 1966. I worked as a deliveryman, distributed handbills, washed dishes, did translations, was a fur trader’s assistant and a correspondent for a Graz daily, ran off photocopies and typed for Prof. Goldmann, while polishing up the German of his lectures, for months was a packer for C. & A. Brenninkmeyer in Neukölln, and did other things besides. My parents still had to help me out with small sums. I wrote for the radio for the first time (manuscripts about Leiris, Blanchot, and Bataille, joint articles with Dr. Friedrich K. about serialized novels or the aesthetics of political speeches). I was determined to work only just enough to make ends meet; I lived on tea (or, for as long as it lasted, a five pound container of cocoa I’d bought on sale) and bread smeared with margarine, as well as on Aschinger’s pea soup (with, at the time, as many bread rolls as you could eat for just fifty pfennigs). I went to the cheapest movie theater (the Olympia near the Zoo train station), becoming acquainted with the West German distributors’ entire stock of Bmovies as a result. I often spent whole days in bed for lack of anything to heat with. Yet I prefer not to be embarrassed, today, over these artistic poses à la Carl Spitzweg, since I did practically nothing else but read in these three years, primarily political literature and MarxismLeninism, carefully & taking my time. However incomprehensible it may seem to outsiders, that saved me a good deal of disappointment and frustration – precisely because I wasn’t “trained” in exhilarating intensive courses in vulgar Marxism, with the blues that inevitably follows the exhilaration. Instead, my own brand of critical optimism enabled me to survive, pretty much intact, the tough times that follow overrated initial successes, whereas they led to resignation in others. Terrible tragedies occurred in the years after 1968 (and we didn’t take very good care of the more fragile among us).

In 1966–1967, I was granted a monthly scholarship of 220 marks at the DFFB; after my first suspension, I was supported by collections taken up by the political student body; my lawsuit against the academy, conducted by the lawyer Horst M., was financed by the Campaign against the Court System.

I was able to survive – although I made no effort to earn a living, but, instead, was busy all day with politics and film, and although I wasn’t willing to sell the results of my work yet (apart from a few essays in periodicals that brought in no more than a couple hundred marks) – thanks only to various shared apartments and communes. I owe a debt of gratitude to them above all. For I was al ways the socially weakest element and, economically, I never did well for long – although that was always my own fault.

I wouldn’t make much of a pimp; my relations with women never even netted me room and board. On the other hand, if I toted up all the meals I ate and movies I was able to go see thanks to girlfriends, I’d come up with a tidy sum.

Running up debts and riding buses and subways without a ticket; good relations with bailiffs.

Only in the past few years has my situation been stabilized. I feel that I’m in a position, now, to sell some of my intellectual work – and also that I’m capable of doing so as well, to some extent. Texts for radio (about Antonio Labriola or various film subjects). Talks, seminars, teaching jobs. Drafting books for publishers. TV jobs as author or director.

P.S. I’m by no means opposed to founding a family in principle. But a family would mean, in my case, radically altering my whole life so that, for example, I could cover the costs of bringing up and educating a child over a period of better than twenty years. I’m not at all ready to pursue the experiments and risky ventures I’m currently engaged in at a child’s expense – and could feel nothing but contempt for a woman who took raising a child off my hands and found fulfillment as a housewife and mother. On the one hand, I can afford “freedoms” that I wouldn’t want to forego and that many people (especially parents) envy me for. On the other, this comes at the price of a conspicuous solitude. I can only weigh my freedom up against my solitude and make my choice. I’ve long since made one that hasn’t changed for a long time (and won’t unless circumstances take a marked turn for the better). It was not insignificantly influenced by the circle of my acquaintances: many couples have taken children on board, only to see new problems crop up – hardly a couple with a child has been able to fulfill its aspirations the way it had imagined fulfilling them without one. This sortof wanting to have a child while also sortof wanting to pursue a youthful lifestyle is surely the worst of all possible solutions. Either or. I know enough colleagues, after all, who have to earn so much every month simply to pay for the bare necessities that they’re prepared to do, and must consent to do, something more than and different from what I’m prepared to. A number of colleagues have shown themselves to be no mean opportunists and sycophants, and I’ve lost all contact with them. I’m aware, nonetheless, of the circumstances motivating them. That’s why I’d prefer, if possible, not to expose myself to such circumstances to begin with.

76.

Thus I pursue, and rather happily, the strange life of a man with privileges but without means. Besides spare furnishings, I own only books, records, and ring binders; I don’t drive, don’t care much at all about clothes, don’t smoke and loathe bricabrac. Yet I’m more of a hedonist than an ascetic = even when I go hungry, I do so as a privileged member of society.

77.

The woman I love wants nothing more to do with me. This almost correct decision has increased my esteem for her. It is understandable for anyone who knows me and her and has read Pavese.

78.

My plans for the 1970s:

A priority project: to produce “Those of Goodwill: A Portrayal of Customs” as a TV movie;

to finish the history of emigration in the Germanspeaking film industry after 1933 – for both the WDR TV series and a book publication (with a British or American publisher, if publishers in West Germany were to pay significantly less);

to direct a porn film (with Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony as background music);

to collect materials on the evolution of the Styrian middle class in the twentieth century – for a detective story inspired by the case of the “The Collegno Amnesiac” (novel or movie);

to finish up an essay about Antonio Labriola, perhaps for an Englishlanguage edition of his works (now that Suhrkamp has announced a Germanlanguage edition);

to carry out further studies in politicseconomicsmilitary history, the initial objective being to produce a TV series on twentieth century warfare; to make various trips, beginning with the one from Mexico to Peru right after Hollywood 1974.

79.

What a provocation: I’ve gone into raptures over Schubert and squares in Rome, have defended craftsmanship, have spouted gossip, have engaged in rationalization – and haven’t once quoted Marx and Engels. Because I’m familiar with the leftist objections raised against me, and because they’re very much on the mark, I’ve been able to come forward as a representative “leftintellectual wanderingJew type from the Austriacisticschizophrenic petty bourgeoisie.” I would kindly ask the reader not to ignore what has motivated me to present West Berlin 1963–74 the way I have and in no other way: I’m disgusted by people who can communicate only by way of their little aches and pains, their pleasures, and their everyday material problems. In contrast, individuals who imagine that, now that they’ve turned to Marxism, their little aches and pains, their pleasures, and their everyday material problems have ceased to exist because they’ve found their theoretical explanation seem to me to be dangerous idealists.

PS: The views expressed in the foregoing are my so-called personal ones. I have not made public anything concerning the concrete issues of socialist filmmaking that concern us, and that I consider to be strictly internal matters.

- 1Julian Volz, “Prolegomena. Straschek 1963 – 74 West Berlin (Filmkritik 212, August 1974)”, Sabzian (2022)

This text was originally published as “Straschek 1963-74 Westberlin” in Filmkritik vol. 8, no. 212 (August 1974), and is published in 4 parts on Sabzian on the occasion of the exhibition and retrospective dedicated to Günter Peter Straschek organised by CINEMATEK and the Goethe-Institut Brussels in collaboration with Sabzian.

The exhibition “Militant Film and Film Emigration from Nazi Germany” runs until 21 June 2022 in CINEMATEK.

The retrospective “Film Emigration from Nazi Germany” runs from 1 to 26 June 2022 at CINEMATEK.

This project was realised with the support of the Goethe-Institut Brussels.

With thanks to Karin Rausch, Julian Volz and Julia Friedrich and the Museum Ludwig Cologne for providing the english translation.

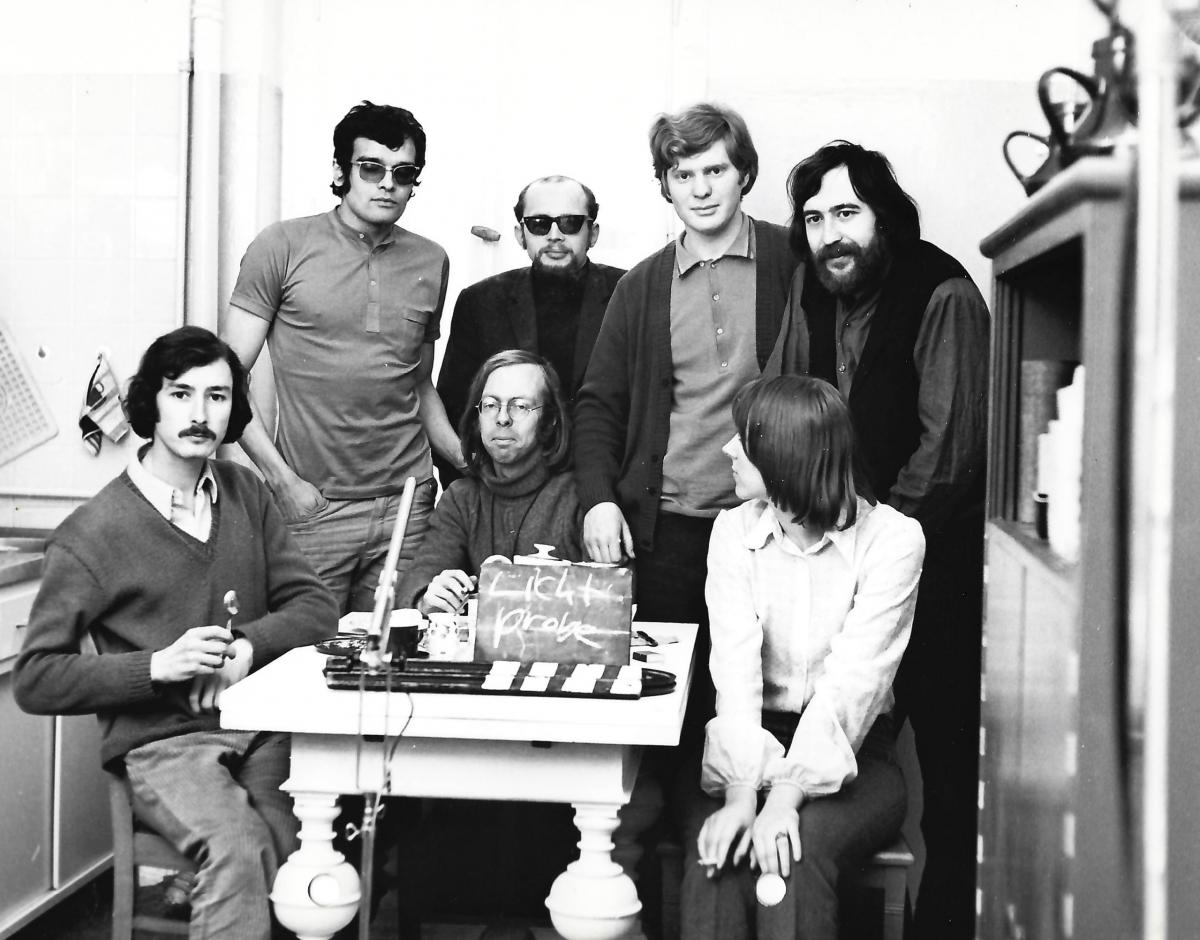

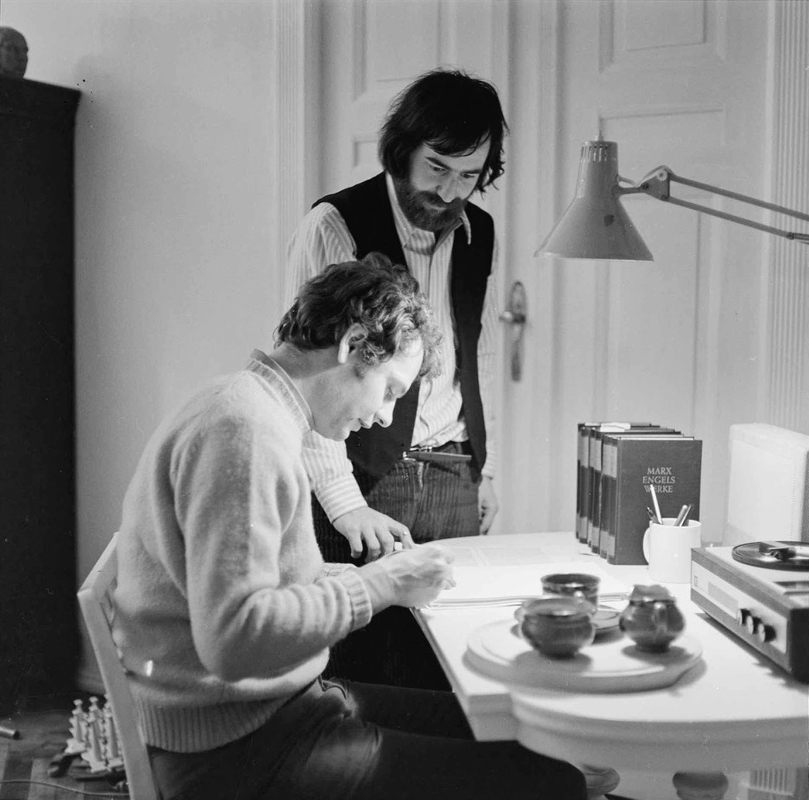

Image (1): Set photo of Labriola (Günter Peter Straschek, 1970). Photo: Michael Biron.

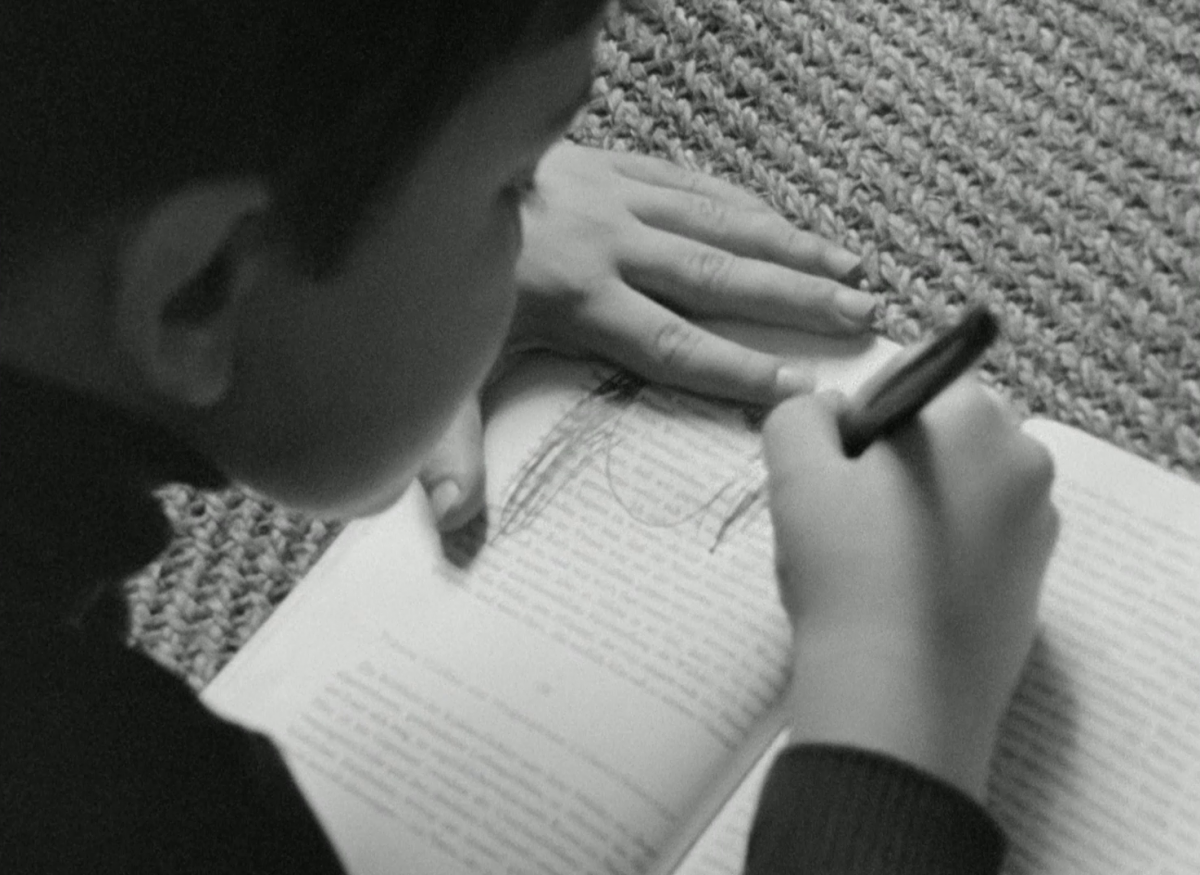

Image (2): Hurra für Frau E. (Günter Peter Straschek, 1967)

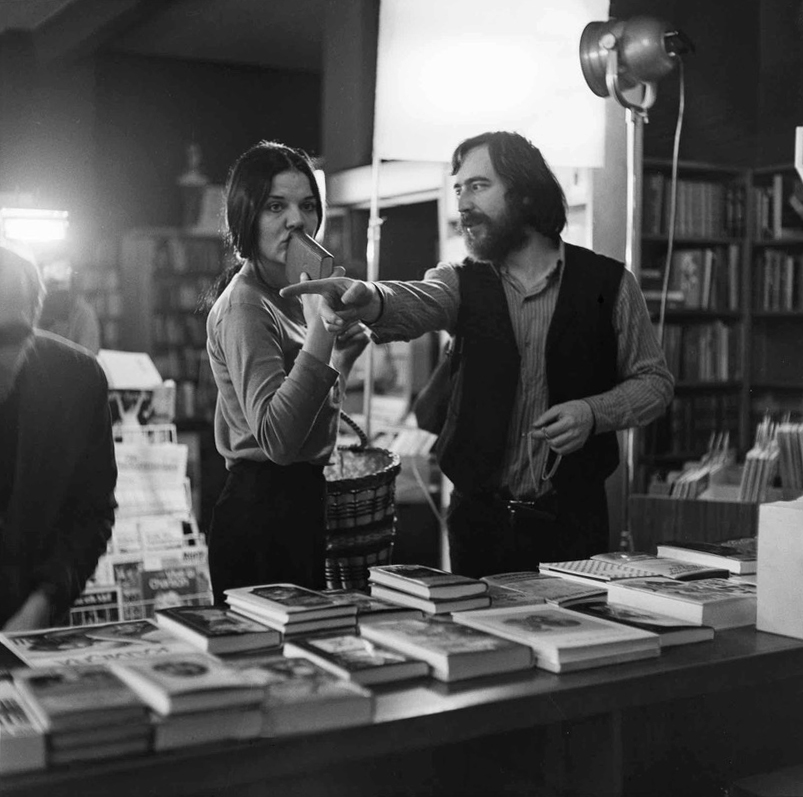

Image (3), (5), (7): Set photo of Labriola (Günter Peter Straschek, 1970). Photo: Michael Sauer.

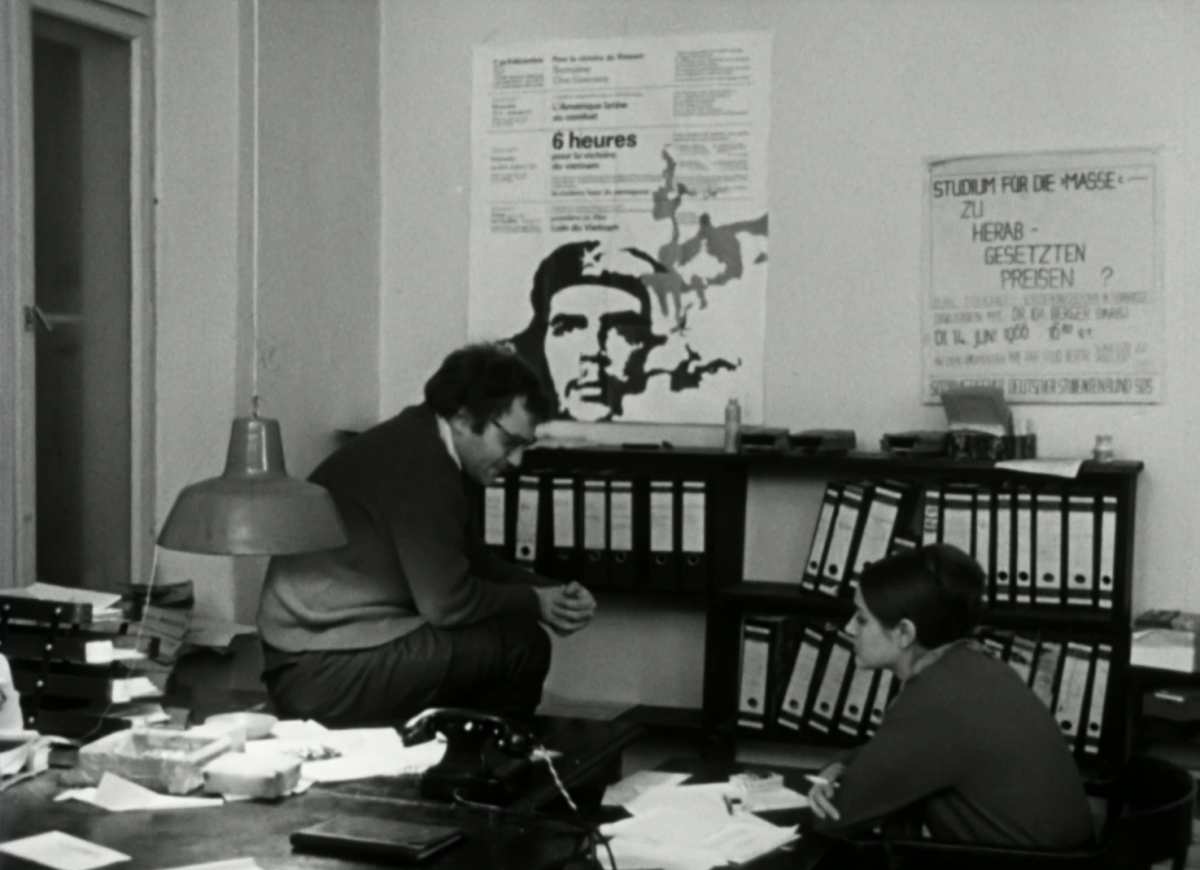

Image (4), (6): Western für den SDS (Günter Peter Straschek, 1968)