The Reception of Farrebique

Reflections on a Polemic

The film was barely finished, and the “Farrebique affair” began – the selection committee of the first Cannes Film Festival eliminated the film from the competition by a vote of seven to two (Georges Charensol and Jeander).

“That Farrebique will not be going to Cannes is an outright scandal,” Maurice Bessy declared (Cinémonde, 10 September 1946). For Pierre Laroche (Patriote de Nice, 2 October 1946), “It is incomprehensible that this film was not selected for the festival.” Robert Chazal spoke of a “scandalous rejection” and a “glaring mistake” (Cinémonde, 2 October 1946). “Beware of a French cinema that disregards a film of the quality of Farrebique, a story of animals à la Jules Renard, for silly films of bipeds à la Gide.”1 (Le Rire, 1 November 1946) “Although some reservations could be made about the arbitrary conception of the subject,” wrote Georges Sadoul, “Farrebique clearly had its place at the festival, whereas the particularly incontinent logorrhea of A Lover’s Return should have been refused even a back seat.”

But the screenwriter of this last film, Henri Jeanson, was the very committee member who fought for the rejection of Farrebique, although he denies that: “Farrebique was not presented to us for approval. I am, admittedly, one of those who find this film boring. I don’t consider cow dung to be photogenic material. I agree that I may be wrong, but I protest against those who claim in bad faith that Farrebique was rejected.” (Spectateur, 15 October 1946)

The film’s coproducer, Paul Leclercq, replied to this in the same newspaper (5 November 1946): “The film Farrebique was presented to the film admission committee on 12 August at the Rue de Lubeck theatre of the Directorate-General for Cinema, in a session that Mr. Jeanson attended. Afterwards we were notified that the film Farrebique would not be admitted to the festival.”

Farrebique was presented at Cannes out of competition. Max Favalelli prophesied: “Farrebique was denied the honour of an official selection. It is not at all impossible, however, that Farrebique will become an unofficial success at Cannes. It would be the first step of a revenge that will surely be total one day soon.” (Paris-Presse, 19 September 1946)

And indeed, Farrebique’s presentation at Cannes was a success. For André Bazin, “This time, the case is heard. The absence of Farrebique at the Cannes Film Festival is a scandal. The preference of a film of such dubious quality as A Lover’s Return, of Mr. Jeanson’s words over Georges Rouquier’s peasant dialogue, is an inexplicable and unforgivable mistake, whose weight the festival will carry in remorse.” (Le Parisien libéré, 2 October 1946)

But the outcome of the festival marked the first recognition of the film – a prize was created especially to honour it, the International Critics’ Prize. From then on, the film profession and specialized journalists were divided into two camps: “One no longer gives one’s opinion on Farrebique. One takes sides.” (Carrefour, 27 February 1947) “Farrebique is no longer a film,” France Roche wrote, “It’s a hobbyhorse word, like ‘Hernani’, ‘Waterloo’ or ‘Dreyfus’. The battle of Farrebique is still taking place. You are ‘for’ or ‘against’ Farrebique. With passion and perseverence.”

Indeed:

“Farrebique is not just a great film or a masterpiece, which is a hackneyed expression. It is something that upsets our most firmly established conceptions of cinema.” (Claude Hervin, Paris-Presse, 3 October 1946)

“With the seriousness of great comedians, critics have decreed that this is pure cinema: the muck of Farrebique!” (Henri Jeanson, Jeudi cinéma, 10 October 1946)

“This brilliant work of craftsmanship opens a new way for cinema.” (Résistance, 13 October 1946)

“...the painful and boring and humiliating Farrebique.” (Le Canard enchaîné, 16 April 1947)

“Farrebique is indisputably a date in the history of cinema.” (Roger Toussenot, Le Libertaire, 17 April 1947)

“Sjöström without personality, that’s what they want us to believe is the best of the best of French cinema.” (Huguette ex-Micro2 , Le Canard enchaîné, 19 March 1947)

“This is by far the most beautiful film we have been able to admire since Jean Renoir’s last French films!” (Pol Gaillard, L’Humanité, 5 February 1947)

“I still believe – against the almost unanimous opinion – that it is a questionable work, but not in any case an indifferent work.” (Denis Marion, Paris cinéma, 15 October 1958)

There are those who proclaim it a masterpiece (René Barjavel, Jean Rougeul, Claude Vermorel, Michel de Saint Pierre); those who consider the film “certainly the most complete and intelligent document of French peasantry” (Marcel Lasseaux, Plaisir de France, March 1947); and those who are more reserved, who reckon it a “compromised success, because its creators may have hesitated to take sides at the right moment” (Jacques Dorlet, Temps présent, 21 March 1947), a paradoxical success since Jean-Pierre Vivet claims that “it is not common to reproach a director for a work that is too perfect. But that is Rouquier’s mistake. By immobilizing these snapshots in an overly meticulous montage, Rouquier has removed their life. In Farrebique, one never feels the irresistible breath that makes a film such as The General Line a masterpiece, despite its weaknesses. Which is a pity, really, because this absence of abandonment, this mastery of every moment by its director, ultimately turns Farrebique into a kind of academic exercise.” (Combat, 22 March 1947)

This “new Battle of Hernani” that was announced by Jean Painlevé in September 1946 (in Les Étoiles) lasted from the “clandestine” triumph at Cannes to the Parisian release in February 1947, fuelled by the awarding of the Grand prix du cinéma français on 17 December 1946, once again an opportunity for Le Canard enchaîné to mock the film: “The jury of the Grand prix du cinéma is still its usual self... After Legions of Honor, now Farrebique, a film that could be called ‘agricultural merit’. From turnips to leeks...” (1 January 1947)

The battle is fought on all fronts: those of realism and authenticity, of the mise-en-scène, of the techniques used, of rhythm, of spirit, of meaning... Most of all, they don’t know how to “classify” the film.

Documentary or fiction?

“With Rouquier, we enter an extreme zone where documentary is pushed so far that it ceases to be a documentary.” (Jean Rougeul, Spectateur, 24 September 1946)

“They will tell us that Farrebique is a documentary and as such defies the laws of fiction film. That’s the flaw. Because, if that were the case, it would be a bad documentary.” (Jacques Dorlet, Temps présent, 21 March 1947)

“Farrebique is a kind of documentary that is as exciting as a detective novel.” (Nord-éclair, 28 February 1947)

“It’s not even a documentary but a film that teaches us exactly nothing.” (Jean Fayard, Opéra, 19 February 1947)

“There is no work that is more – or better – composed than Farrebique. The contribution of the director in no way besmirches the truth of the images; on the contrary, it serves it, reinforces it, gives it extraordinary acuity. So please don’t say that Rouquier has made a documentary! In reality, he has made an admirable work of art along documentary lines.” (Roger Régent, Tout Paris, 12 February 1947)

“An admirable sociological documentary” for Jean Quéval (Fraternité, 10 October 1946) who adds (Entente, March 1948): “Farrebique is not an album, it’s a symphony.” “Musically and cinematographically, a pastoral symphony; not like Delannoy, but rather, if you will allow me to say so, like Beethoven.” (Georges Altman, Franc-tireur, 2 October 1946) “A true pastoral symphony,” Georges Magnane writes (L’Écran français, 18 February 1947), continuing: “The strong value, the shattering originality of this film lies in its totally authentic, new presentation of peasants.” But three columns further on, Jean Vidal wonders: “Is it an eclogue? Is it a pastoral? Should we evoke Virgil in the context of Georges Rouquier’s film?” O’Brady responds (Cinémonde, 4 February 1947): “Farrebique is a rural and realist symphony-documentary drama-pastoral with a pinch of The Rite of Spring. It’s a celluloid poem of powerful and tender beauty.” A judgment invalidated by Jean José Marchand (Climats, 20 March 1947): “From a documentary angle, Farrebique is a true masterpiece; in the future, it will be shown as a document of absolute truth on the life of French peasants in poor regions. But when it comes to Georges Rouquier’s creative disposition, we must acknowledge its shortcomings. The gap between The General Line and Farrebique is the gap between an auteur and a commentator.”

“Painting has been said to be ‘nature as seen through a disposition’,” J. Falga says, adding: “The same could be said of Rouquier’s film.” (Cahiers de notre jeunesse, April 1947)

According to Georges Sadoul, “The importance of Rouquier’s work is not that it revamps the documentary, but that it goes beyond it, joining the new European avant-garde which has recently emerged in films such as Lindtberg’s The Last Chance, Clément’s The Battle of the Rails and Rossellini’s Paisan.” (Les Lettres françaises, 21 March 1947)

Even René Clément, the director of The Battle of the Rails, took part in the debate (in an interview by Jean Queval in L’Écran français, 16 October 1946): “Cinema must provide an answer to the spectator’s social anxiety and the spectator must be able to find hope in it – not, of course, the optimism of an ostrich, but the hope of lucidity... It’s a conception that, I think, can be expressed through aesthetic and social realism, without ignoring the contribution of the documentary. In this respect, a film such as Farrebique is important.”

The second aspect of the debate revolves around the “capturing” or “reconstruction” of truth, in short, around authenticity and “cheating”.

Henri Jeanson takes the offensive: “Mr. Rouquier is an honest cheat but a cheat nonetheless.” (Jeudi Cinéma, 10 October 1946)

Jean Rougeul replies: “The blatant authenticity of what we see is the only thing that counts. It’s the strange feeling of finding oneself alive in an image, in a reflection projected on the screen, which touches the sensibility of the spectator.” (Spectateur, 22 October 1946)

“Cinema in its purest form, life surprised by the screen,” Georges Altman exclaims (Franc-tireur, 2 October 1946), which is echoed by the Swiss critic Jean-Pierre Moulin: “This unvarnished film, in which everything was captured on the spot, in its natural setting, at the right moment, is an example of patience and a masterpiece of both truth and wonder. It verges on the most overwhelming greatness because it’s very close to the little things in life.” (La Gazette de Lausanne, 17 October 1946)

“Why didn’t we realize sooner that the camera does not accept cheating?” Simone Dubreuilh asks, defending “the festival washout” (Paris cinéma, 24 September 1946): “After seeing Farrebique by Georges Rouquier, It Happened at the Inn, although not bad in its genre, seems like a farce. The former is life filmed like the news, news that is willed, chosen, animated by thought. The latter is mere theatre.” Jean Oberlé adds: “An astonishing, captivating film that exchanges the twaddle of filmed theatre and the facile spirit of screenwriters for something solid that touches the very essence of France, in keeping with the peasants painted by Le Nain or described by Restif de la Bretonne qua cultural heritage.” (Vogue, January/February 1947)

Jean Queval is definite about it: “The documentary is indisputable, even in its dialect.” (Entente, March 1948)

For Roger Régent, “Rouquier has managed both to remain within the realm of the most accurate truth and to escape documentary dryness.” (Tout Paris, 12 February 1947)

But Jeanson strikes back: “One doesn’t go to the cinema to see a washerwoman brilliantly beating real laundry in a real stream. [...] Farrebique’s admirers praise its authenticity. There’s nothing more fake than this authenticity, nothing more artificial than this truth. Let me explain. To film his documentary, Mr. Rouquier had a technical crew of electricians, sound engineers, cameramen, ... He did not act as a news operator. He did not catch the truth red-handed in all frankness. He behaved like a director.”

Behind this quarrel appears the main grievance against the film: boredom.

“Farrebique is an endless documentary about life on a farm. A slice of life. A terribly indigestible slice. It went on and on. It was no longer cinema, it was a magic lantern.” (Paris matin, 10 October 1946)

“A film that was made in a simple way, with the love of a craftsman taking great pains over an object, a film that is exciting and that we would like to see last even longer, such is Farrebique.” (Jean Oberlé, Vogue, January/February 1947)

“The film is extremely boring... I’m not going spend my holidays in Farrebique.” (Le Canard enchaîné, 25 September 1946)

“I was not in the slightest bored by this actionless film, which moves forward sluggishly with the tireless hardness of peasants and the certainty of ploughmen.” (Pierre Laroche, Le Patriote de Nice, 2 October 1946)

“Farrebique is not a scientific documentary or a report on our beautiful countryside. It claims to tell us the life of a peasant family, and it does so in such a slow and boring way that it is impossible to find it interesting.” (Regards, 8 November 1946)

“It is said that happy people don’t have a story. That’s probably why we can’t recount Farrebique. But it would be wrong to fear a monotonous and boring film.” (S. Dalens, La Vie catholique, 22 December 1946) And yet this is exactly the opinion of the anonymous critic of Carrefour (27 February 1947), of Jacques Dorlet (Temps présent, 21 March 1947), and of Jacqueline Lenoir: “The incessant asceticism turns the film into a skeleton; you get bored inside this farm like Jonas in the belly of the whale.” (Gavroche, 13 February 1947)

“Farrebique moves us and makes us yawn,” Carrefour thinks. Marcel Carné protests (La Rue, 4 October 1946): “The deeply moving thing in Rouquier’s film is its purity, along with a love of nature of an extraordinarily lyrical force.” A purity that Jacques Prévert, at the end of a screening, likened to that of “a Proust looking at common people” (reported by Minnie Danzas, Le Soir, 3 September 1946). France Roche is more reticent: “Devoid of lyricism, Rouquier is interested in babies jumbled together with ducks, harvests, and roses. Death, to him, is not a chatty ghost but a heart that’s no longer beating.” (Cinévie, 18 February 1947)

For Jean George Auriol, this “objective” approach is the expression of the auteur’s lyricism: “In accordance with the natural disposition of medieval or modern French artist-artisans, Rouquier’s inclination is intimacy. A few whispered reflections, whether or not in patois, a thought written all over an open face, ears strained towards some hoped-for or feared sign – they are notations of a melody whose lyricism is more often that of a cat purring in hot ashes than that of roosters and peacocks shouting at the top of their lungs.” (L’Écran français, 2 October 1946)

This discretion, admired by some and considered as “dryness” by others, is thus measured by its poetic quality.

“All those who have seen Farrebique were mesmerized by the intense poetry of a work whose most authentic virtue is that of truth,” states Max Favalelli (Paris presse, 19 September 1946)

Many filmmakers and critics were indeed sensitive to it.

Jean Painlevé: “A large part of the poetry that emerges from this film has to do with the unsaid, with the faces whose inner life is hard to guess. To achieve this amazing feat required a director imbued with the life of farms and fields.” (Les Étoiles, 24 September 1946)

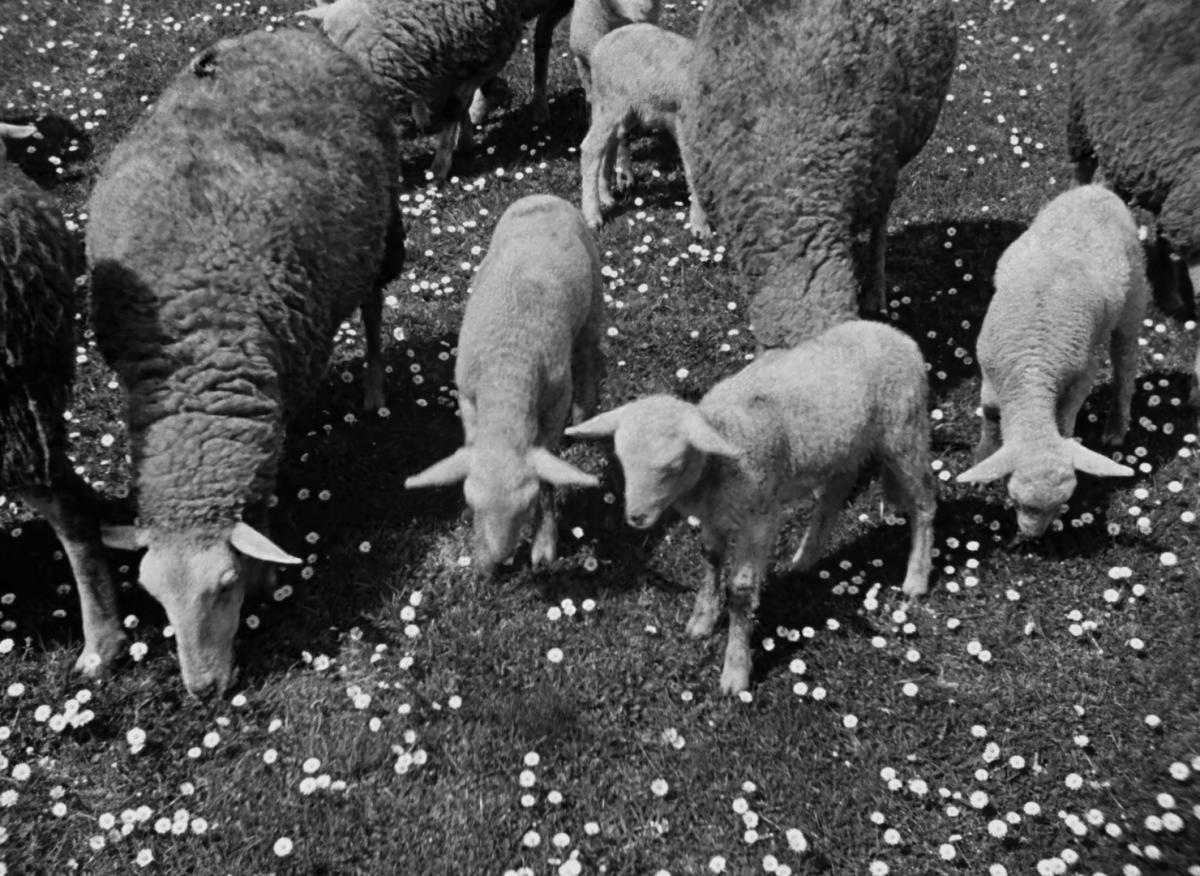

Jean-Pierre Moulin: “With the inhabitants of a farm, plants, meadow flowers, domestic and wild animals as his only actors, he created the most astonishing poem that cinema has ever given to us.” (La Gazette de Lausanne, 17 October 1946)

Jean George Auriol: “It took a poet to move us with the mud of paths, a call to soup, the sighing of a woman who has just given birth, nocturnal animals waking up at dusk, a multiplication table, the clever tricks of a grandfather, the brilliance of a ploughshare in the sun, the bursting of a bud, etc. but it also took a poet to evoke the absolute freedom of a child in control of a stream in which he’s installing little mills, the enchanted strength of a child using a dog to order the cows about, the full happiness of a child in silent conference with a ruminating ox.” (La Revue du cinéma, January 1947)

Marcel Huret: “The peasant films we know, even the best ones (I am thinking of Harvest and It Happened at the Inn), cannot be compared to this unique film, which is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful poems dedicated to the glory of the earth since Virgil.” (L’Écho de Normandie, 27 March 1947)

Jean Vidal, on the other hand, admits that he is “not sensitive to Farrebique’s poetry” and thinks that “to pull off this kind of film poem would have taken a certain touch, which Rouquier lacked, and especially a unity of style and inspiration.” (L’Écran français, 18 February 1947)

“He is not a poet,” Jacqueline Lenoir adds, “but a good cinema craftsman. He knows how to see without imagination, how to learn without consequences.” (Gavroche, 13 February 1947)

And Jean Fayard, peremptorily: “Everything is poor here, narrow, devoid of imagination, deprived of poetry, extremely stretched out.” (Opéra, 19 February 1947)

“Let’s not overindulge in this filmed ‘bucolic’,” the anonymous critic of La Gazette provençale writes (31 March 1947). “We know all too well that this Rousseau-like poem hides what Zola, Maupassant, and Mirbeau have depicted in a superior way. That’s what the film should have provided us with, not with this conventional view of a peasantry in accordance with the best stereotypical traditions.”

References and comparisons to Farrebique abound:

“This is a far cry from realist smutty peasantry à la Zola, from romantic peasantry à la George Sand” (Edmond Sée, Normandie, 5 April 1947); “No rural idyll or peasant drama here. Farrebique is closer to Virgil than to George Sand or Henry Bordeaux” (André Lang, France-soir, 8 February 1947); “Don’t expect to find in Rouquier the bland accents and romantic tremors that the worst kind of regionalist literature has introduced into the genre. Nor a taste of eclogue à la Virgil. And yet, there are none of the ‘realist’ exaggerations à la Zola, which are as false as René Bazin’s watercolours or Henry Bordeaux’s chromolithographs.” (Pierre Scize, Le Fait du jour, 28 January 1947)

Jean Cocteau declares (as quoted in L’Époque, 23 March 1947): “Cinema is going through a time that is comparable to French theatre under Antoine: the return to natural life. The most remarkable recent films, such as Paisan and Farrebique, prove it.” Le Grelot agrees (18 March 1947): “It’s a film that Antoine would have loved, who filmed The Earth and at times showed a similar concern to film the minute details of country life.” Henri Jeanson says the opposite: “It’s taking the audience for livestock to offer them these dreary images that would have made Zola yawn, Monet flee, Renoir sigh and Antoine pronounce one of those ‘goddamn, let’s get the hell out of here and go drink a beer!’ which made him look so sympathetic.”

“Some will talk about Virgil or Giono,” Maurice Bessy writes. “One day they will realize that it will be easier to simply talk about Rouquier.” (Cinémonde, 10 October 1946)

But for the time being, Rouquier still needs some solid backing:

“French by nature, Rouquier is only comparable to much-admired masters of different origins: Flaherty, Ivens, Dovjenko.” (J.G. Auriol, La Revue du cinéma, January 1947)

“The grandfather’s funeral bears comparison with the very best of cinema, evoking Dovjenko’s unforgettable peasant epic Earth.” (G. Sadoul, Les Lettres françaises, 21 March 1947)

“What endows this work, moulded from the most banal material, with a rare magnificence, is the fact that the director managed to communicate the movement and tone of a poem whose lyricism reminds us of the Soviet film Earth by Dovjenko.” (Raymond Barkan, Le Patriote de l’Oise, 26 February 1947)

“This lyricism gives Farrebique a meaning and a value that is not only very moving but also very rare, for there are very few examples of it in the immense repertoire of cinema, unless we go back to the great ‘Swedish School’ or to films like Women of Ryazan and Turksib that marked the early stages of Soviet cinema.” (René Jeanne, La France au combat, 13 February 1947)

The references also work in the critical sense: “Only Robert Flaherty in Man of Aran and Eisenstein in The General Line have been able to overcome the traps set by this unrewarding and dangerous subject matter.” (Denis Marion, France illustration, 22 February 1947); “Farrebique can only disappoint those looking for the French equivalent of Outskirts or The General Line because Farrebique is, despite some very beautiful parts, nothing but an honourable, excellent documentary.” (Claude Schnerb, La France au combat, 20 March 1947)

A reference that makes Jean Painlevé smile: “I still remember the critical reception of Eisenstein’s The General Line in 1925: ‘What’s the use? We have had tractors in France for a long time.’” (Les Étoiles, 24 September 1946)

Other filmmakers that Rouquier is said to be close to are Vigo and Renoir. For Marcel Carné (La Rue, 4 October 1946): “Farrebique today strikes the same different note as Zéro de conduite and L’Atalante when they were released.” Painlevé: “Finally we are in front of the work that should start a new cinema, joining Jean Vigo, to whom Rouquier seems the most closely related.” And Pierre Kast adds: “This passion for truth, combined with his mastery of the profession, makes the quarrel over Farrebique a battle for freedom of expression in cinema, and Rouquier the successor of Vigo.” (Action, 4 October 1946)

“No trace of Jean-François Millet’s The Angelus. Nothing but an overwhelming sense of the poetry of the land, a nearly pagan sense of the world, which sometimes calls to mind the Jean Renoir of A Day in the Country.” (J. Homolle, L’Enseignement, 15 June 1947)

“If I mention Renoir in relation to him, it’s because there seems to be a subtle connection between them – the instinct that drives them towards the most moving things in nature and the simple way of bringing its authentic secrets out into the open. This produces films with an innocent appearance and an infinite aftermath. In this sense, Rouquier’s film reminds us of Jean Renoir’s magnificent Toni,” Jean Rougeul writes in La Rue (4 October 1946). The reference to Toni is all the more interesting because Rouquier’s approach is based precisely on certain experiments by Renoir in this film, mainly its refusal of studio recordings and its direct sound.

“I have been one of the staunchest supporters of Farrebique, a genuine masterpiece, a slice of everyday life,” Carlo Rim says. “In order to survive, to escape the asphyxiation that threatens it, cinema has to desert these unhealthy sheds, the studios. It has to open its windows wide to the sun, to fresh air, to life; to soak up light, movement, truth...” (Films pour tous, 28 January 1947)

“With only small, mediocre and narrow things, what merit to achieve this great thing, washing away the perfumes of Hollywood and other places!” (Le Rire, 1 February 1947)

“A barely constructed script,” Jacques Dorlet criticizes (Temps présent, 21 March 1947). To which Painlevé replies: “A script so clever in its simplicity that superficial minds consider it a lack of script. Minimal dialogues that are only there to suggest. No theatre, no confusion of genres.” (Cinémonde, 24 September 1946)

“There is no – or hardly any – story. No stars, no actors even. But Rouquier had better things to show us. He had life, reality. His art is not distorting it.” (Le Parisien libéré, 21 March 1947)

“This lack of a story does not, however, make Farrebique completely different from others films. Georges Rouquier’s search is all the more gripping because the young filmmaker has played the game. Like other films, his film has a script, dialogue, and actors.” (Georges Charensol, Les Nouvelles littéraires, 6 February 1947)

That’s one of the central themes of the polemic instigated by Guillot de Rode in Le Courrier de l’étudiant (19 March 1947), the actors: “A film whose script was carefully written, whose scenes were rehearsed with precision, by improvised actors, agreed, but actors all the same; that’s where, as far as the human performance is concerned, you leave the documentary and discover ACTING, whether or not by an amateur, whether or not the amateur was a farmer.”

“Farrebique is not acted. It’s lived,” L. Ch. Debelle says (Le Libre Poitou, 28 March 1947). “This film does not feature professional actors, but real peasants, not invented peasants who have studied in front of the mirror how to take on a peasant appearance, adding make-up for a peasant complexion. The mise-en-scène is particularly delicate here, because nothing is more difficult than having non-professionals act and telling them not to “act” but to simply repeat their normal everyday acts in front of the camera.” (Jean Painlevé, Les Étoiles, 24 September 1946)

Which is what Pierre Chartier questions: “When peasants have to play their own character, they are clumsy, they are awkward, in other words: they are bad.” (France libre, 18 March 1947)

Jean Rougeul protests: “...real peasants that Georges Rouquier managed to direct, despite the difficulties. That is the difference between a real director and a maker of films.” (Spectateur, 22 October 1946)

“While some of the peasants marvellously portray their character, we can’t say the same thing about all of them. We also wonder whether it might not have been better to have the roles played by good professional artists who might have evoked reality better than real locals, who were clearly intimidated by the eye of the camera.” (Films pour tous, 4 March 1947)

To which Jacques Dorlet, however guarded about the film, retorts: “Professional actors could never match up to the absence of art that marks the awkwardness of these peasants who are so without effort.” (Temps présent, 21 March 1947)

“This family lives, it’s as simple as that. Georges Rouquier has watched them live, day after day, season after season.” (L’Homme nouveau, 15 March 1947)

“On the pretext of realism, Mr. Rouquier shows a peasant troupe in pitiful exercises in photogenicity... Everybody sounds fake, in natural décors carefully framed by Mr. Rouquier. The Angelus by Rouquier,” Henri Jeanson mocks once again, under his pseudonym of Huguette ex-Micro (Le Canard enchaîné, 19 March 1947)

“It Happened at the Inn, which is a very good French film, cannot match Farrebique. The former shows décors and artists disguised as peasants; the latter shows a real farm and real peasants.” (P. L. Pamelard, Forces françaises, 3 October 1946)

Jacques Becker, the director of It Happened at the Inn and a fervent defender of Farrebique, has some reservations about the “acting”: “All the men seem a little embarrassed, only the woman in the film, the young mother, is perfectly at ease. It seems like she has ten years of theatre experience.” (L’Écran français, 4 February 1947)

“After The Battle of the Rails (a film performed by real railway workers), the success of Farrebique brings us a brilliant confirmation of the thesis that we have often defended here, namely that there will be no film art as long as we resort to ‘stars’.” Guy Breton’s excessiveness here (L’Époque, 5 February 1947) is tempered by Mr. Guillon in Lundi matin (10 February 1947): “The peasants of It Happened at the Inn were certainly more at ease in front of the camera. Let’s not talk too hastily about removing the stars.”

But, for Simone Dubreuilh, “Ten or twenty years from now, film stars will be as anachronistic as sedan chairs or the Louis XIV coach of the Sultan of Morocco.” (Paris cinéma, 24 September 1946)

Another subject of dispute is the use of visual effects, of slow-motion or accelerated shots of a “scientific” nature.

While, for Georges Sadoul, “the visual effects that tap into Méliès’s divine naivety contribute to Farrebique’s lyricism” (Poésie 47, March 1947), “the accelerated shots showing the germination and blooming of leaves and flowers would have a place in a documentary, but not here”. At least, according to Denis Marion (France illustration, 22 February 1947), who adds: “As for the other microscopic views showing the circulation of sap, they seem to indicate a manifest lack of taste. Nothing could be further from a peasant’s notion of spring than this abstract and scientific point of view.”

Raymond Barkan (Le Patriote de l’Oise, 26 February 1947) is of the opposite view: “The accelerated shots, combined with Rouquier’s eloquent montage, gives the germination of seeds, the opening of corollas, the unfolding of ferns the value of superbly poetic themes.”

“The only criticism this film deserves is perhaps that some of these techniques are used a little too often and give an impression of length and monotony.” (J. J. Gautier, Le Figaro, 8 February 1947)

“He broke and rebuilt the rhythm of things in order to bring it to our visual perception. He did not use slow motion as an effect, but only to make us see the invisible things: the movements of a bird in flight, the effort of a blooming flower... Everything that used to be a lab experiment, becomes the total manifestation of life in Farrebique.” (Pierre Leprohon, Camping plein air, November 1946)

“The power of an undertaking such as Farrebique”, Georges Altman says, “is to have directed the gaze of the cinema at peasant life, as the lens of a microscope does with regard to its object.” (L’Écran français, 5 November 1946)

“He looked at these peasants from Aveyron as the entomologist Fabre looked at his insects live in Sérignan. This does not prevent Fabre from being one of our leading writers and Rouquier, what with his choice of images and their montage, from fully revealing his strong personality.” (Georges Charensol, Juin, 17 September 1946)

“Georges Rouquier looked into his small rustic world with the impartial curiosity of an entomologist, and his camera became a revelatory magnifying glass. His protagonists are neither beautiful, nor good, nor even bad. They exist as plants or animals do. They are real.” (Pierre Laroche, Le Patriote de Nice, 2 October 1946)

“An observer with a novelist’s refinement and an entomologist’s patience, capturing moments rather than painting a picture with effect, armed against both emphasis and convention, Rouquier possesses a rare gift: the gift of love.” (Jean George Auriol, L’Écran français, 2 October 1946)

The criticism also concerns the technical execution: photography, montage and sound recording.

Denis Marion is categorical: “The photography is often mediocre; the sound is always inadequate, and the montage is clumsy.” (Combat, 2 October 1946)

Jeanson speaks of “mediocre photography animated by clumsy amateurs” (Jeudi cinéma, 10 October 1946), while André Bazin is full of admiration: “The slow and massive cycle of the seasons, the solemn rhythm of the day, the variations of time, the internal life of the realm of plants and animals are the prodigiously photogenic actors of his film.” (Le Parisien libéré, 2 October 1946) To which Jean Fayard remains insensitive: “Beautiful images? From a completely impartial standpoint, I counted five or six. The rest is shit.” (Opéra, 19 February 1947)

“The photography is flat, without density, the montage is clumsy. Mr. Rouquier seems to have the sensibility of a pitchfork handle.” (anonymous, La Gazette des Iettres, 5 April 1947)

Denis Marion insists (France illustration, 22 February 1947): “On the whole, the montage is deeply flawed, even though it took nine months.” Marcel Carné reacts (Cinémonde, 24 September 1946): “It has been said that this film was poorly edited; that’s not true. It has been edited as it should have been.” Jean George Auriol nuances this opinion (L’Écran français, 2 October 1946): “A montage that is as clumsy in the last third as it is ingenious, vivid and fluid in the first half.” He does this without however tempering his praise: “Farrebique’s images don’t mean much by themselves, apart from the role they play as words, notes, chords, verses in the general montage of the work. Here, the montage is no longer merely the result of sorting out the best shots, of marvellous moments, and of an effort of rhythmic composition – it is a real second-degree conception of the film.” (La Revue du cinéma, January 1947)

The reservations have less to do with the sound design, which is generally considered as original: “Farrebique is not a talking picture like so many other films; it’s rather a sound film in which all the noises of life are mixed, those of the farm, of the land and the people, all melted into one harmony of great music.” (Julien Regnault, France libre, February 2, 1947)

“The noises are not made with disk recordings and patented foley artists slapping their thighs to imitate the galloping of a horse. Don’t tell me that exactitude is useless.” (Jean Painlevé, Les Étoiles, 24 September 1946)

“This ring of truth also owes a great deal to the sounds recorded during the shoot,” Raymons Barkan writes in Le Patriote de l’Oise (26 February 1947). The use of this sound, however, is not immune to sarcasm: “On the close-up of an artery that stops beating, the sound of a tree falling is superimposed. This metaphor comes close to the most superficial of literary clichés, of the Almanach Vermot type.” (Jean-Claude Vignes, La Revue Montalembert, May-June 1947)

André Bazin corrects: “If Rouquier was the first who dared to record the peasant’s dialogues and the authentic noises of the night in direct sound (whereas the sound recording remains the terror of documentary filmmakers), he knew that the slight imperfection of this technique, the inevitable awkwardness these improvised actors would show in front of the microphone, was still a thousand times preferable to any postsynchronization. The result is there.” (Conquêtes, April 1947)

And Georges Sadoul believes that “Farrebique’s greatest technical discovery is the use of sounds, noises that had never been heard in the cinema. This is probably the first time that we hear in the cinema the thousands of inaudible noises that make up the silence of the countryside.” (Poésie 47, March 1947)

“Farrebique, a work that – at long last – brings something new to the art of filmmaking,” proclaims Marcel Idzkowski. (Opéra, 2 October 1946)

“Like The Battle of the Rails, Farrebique is written in a style that many would call revolutionary and that we would describe much more simply as human and truthful. It’s revolutionary insofar as the truth must be revolutionary in order to reach the screens.” (J. F. Narbé, France vivante, 19 February 1947)

Jeanson replies: “Farrebique, revolutionary? In what? Revolutionary in postcards? For a revolutionary, Mr. Rouquier is a little late. He’s just a late disciple of Antoine – naturalism having failed to die, here comes Rouquier...” (Jeudi cinéma, 10 October 1946)

But for Marcel Carné, “This film is incredibly powerful and brings about such a revolution that it will inevitably find its place on its own merit.”

In the same issue of Cinémonde (24 September 1946), Jacques Doniol-Valcroze recounts the following comment by Jacques Becker: “Farrebique is a revolutionary film. Revolutions are always ahead of their time. The real avant-garde film of the last years is not Citizen Kane, it’s Farrebique.”

Jeanson, however, doesn’t give up and opens a new line of attack: “Uninterested by nature and conformist by taste, Mr. Rouquier shows us idyllic peasants as seen in Les veillées des chaumières.”

“Demagogy and cow dung.

- Don’t move! We’re shooting! Here we are, sir!”

Reactions of supporters: “This is not a propaganda film preaching a return to the land, as Vichy could have shown us.” (La Vie heureuse, 27 November 1946)

“It’s not a ‘return to the land’ kind of film. You might as well say that Gates of Night is a return to the chapel or Beauty and the Beast a return to the candelabra.” (O’Brady, Cinémonde, 4 February 1947)

One last grievance remains, the film’s lack of a “social” reality and the filmmaker’s “detachment”.

“Obviously, I would have liked Rouquier to take sides,” regrets Pierre Laroche. “This would even be my only criticism of his film, but he would reply that such was not his intention.” (Le Patriote de Nice, 2 October 1946)

“It’s a very beautiful film, screaming with truth, which has only one flaw, it sidesteps social issues,” Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes tells this same newspaper (3 October 1946).

“I don’t think he sufficiently brings the peasants into the economic and social life of their time; for example, we never see them worrying about the price of wheat or fertilizers, or about the fate of their country, to which most of us pay so much attention.” (Pol Gaillard, L’Humanité, 5 February 1947)

“I, personally, would have liked these peasants to be more involved in the life of their time, despite their geographical isolation.” (Gilbert Badia, La Marseillaise, 12 February 1947)

“It’s pretty strange that the collective problems affecting farmers today are never mentioned.” (Raymond Barkan, Le Patriote de l’Oise, 26 February 1947)

“There is a whole social side that was not sufficiently brought to light, despite the somewhat skimpy passages of the threshing machine, the church and the café.” (Guillot de Rode, Le Courrier de l’étudiant, 19 February 1947)

“Farrebique only provides us with a very limited aspect of peasant life. Rouquier betrayed his intentions. He was a victim of a certain impressionism, which made him neglect psychological truth in favour of the beauty of the eternal gestures of life, love, and death.” (Claude Després, La France catholique, 18 April 1947)

A judgment that Michel de Saint Pierre does not share: “The filmmaker did not want to represent the life of a peasant family from Rouergue at a given time. He wanted to celebrate humankind’s eternal engagement with the land. What we have here is a document of general importance, whose fierce sense of modesty has no use for current events.” (Témoignage chrétien, 21 March 1947)

And France Roche concludes: “Ignorant of regionalism, folklore, and propaganda, the story of Farrebique neither criticizes nor advises. It shows.” (Cinévie, 18 February 1947)

So, all things considered?

“Farrebique is, if you like, eternally topical. You can show it to the Chinese, Hindus, Russians, Danes, Eskimos. They will understand.” (Georges Altman, Franc-tireur, 2 October 1946)

“... a mediocre, artificial, conventional, and tedious film that hides real pretention under false simplicity.” (Henri Jeanson – Huguette ex-Micro, Le Canard enchaîné, 19 March 1947)

“More than a film that is naturalist and poetic at the same time, Farrebique is a work implacably marked by the inconstancy of our time.” (Jacques Chastel, L’Alliance nouvelle, 4 April 1947)

“I don’t know if it’s a masterpiece, but I am sure of the exceptional quality of this extremely beautiful film poem.” (Pierre Laroche, Le Patriote de Nice, 2 October 1946)

“If only films like Farrebique were made, no one would go to the movies anymore, but among all the other productions, Farrebique looks like an exceptional masterpiece.” (Charles Ford, Film Information Agency, 20 November 1946)

“If this example were followed, it could have dire consequences. Why not turn the life of metalworkers, sardine fishermen, or crossing keepers into feature films?” (Raymond Jarry, Le Miroir de la semaine, 2 March 1947)

“Farrebique is in a class of its own within French cinema; it opens a dead-end street and must be considered as an exceptional and wholly successful event, and not as a model.” (Jean-Pierre Morphé, Bref, 15 February 1947)

“It seems to me that Georges Rouquier’s achievement cannot serve as an example. One will never again come across peasants speaking with the naturalness of the farmers of Farrebique.” (L’Époque, 24 January 1948)

“Farrebique represents a date in the history of French cinema; a masterpiece was born but not a school.” (J. Homolle, L’Enseignement, 15 June 1947)

The debate remains open, even if the originality of the approach ultimately found two visionary analysts in the persons of Jean Rougeul and André Bazin.

“That Rouquier was able to find in front of his camera the very tender spot where a simple document touches the heart more deeply than dramatic action, is obviously sensational and is enough to classify him, from now on, as one of the greatest directors ever.” (J. Rougeul, Spectateur, September 24, 1946)

“I consider Farrebique a major event. One of the very few French films, together with Malraux’s Man’s Hope, that had a premonition of the realist revolution that cinema needed. This revolution has broken out in Italy quickly, and filmmakers there have managed to draw such perfect lessons from it in less than two years that I fear they are already concealing their conventionalism.” (André Bazin, Esprit, April 1947)

These last words are also by André Bazin, a sort of quip: “In his paper, a film critic who is undoubtedly overly distinguished complains that he has seen cows dropping dung, rain falling, sheep bleating, peasants speaking in patois, which, according to him, is enough to make you tired of the countryside. Enough to make you tired of film critics.” (Conquête, April 1947)

This text appeared originally in Images Documentaires 64, third and fourth trimester 2008.

With thanks to François Porcile and Catherine Blangonnet-Auer.

Milestones: Farrebique ou les quatre saisons takes place on Thursday 18 February 2021 at 19:30 on Sabzian. You can find more information on the event here.