Communist Photosynthesis

“Neither the paradoxicality of what is happening, neither the scale of what has already happened, nor the perspective of what awaits the world to experience – can be grasped by a single consciousness. We know firmly – ahead there will be victory over darkness. Ahead – there is light. But we are still not able to assimilate its rays, to examine the new life in these new rays, to move along the new paths illuminated by them. We foresee, have a presentiment, and have a foreboding of it. But this light is only now being born in the truly apocalyptic madness in which the universe is now enveloped. Humanity is stretching out to it, toward this unknown light of the future.”

– Sergei Eisenstein, 19421

“In the yellow of the sempiternal rose,

Which unfolds by degrees and dilates and breathes back

The odour of praise to the sun which keeps perpetual spring.”

– Dante Alighieri, 13202

In the first part of the film O somma luce (2010) Jean-Marie Straub leaves us in the dark for just over seven minutes (a couple of seconds longer in the second version) with a recording of the first performance of Edgard Varèse’s Déserts (Paris, 1954).3 The first two and a half sections of Déserts are thereby spliced together with the second half of the final canto, XXXIII, of Paradiso from Dante’s Comedìa (1320). The overall shape of the Comedìa, which is a long and gradual movement from darkness into light, is with Straub an irruption of light and words.

Varèse’s piece brings together his ideas on how to organize sound and music (and therefore time) away from the classical tradition, through the concepts of duration, intensity, frequency, and timbre. Déserts also features interpolated tape recordings of electronic sound which were played into the auditorium. It is this first interpolation which produces the eruption of boos, abuse (“This is a scandal!”), and hisses from the audience attending the premiere, adding another layer of sound. Straub brings these un/intentional forms into juxtaposition with Dante’s strict metre and rhyme. He also honours Varèse’s intention for Déserts to be experienced in company with a film,4 one that would have to be “in opposition with the score. Only through opposition can one avoid paraphrase... There will be no action. There will be no story. There will be images. Phenomena of light, purely.”5 With Straub, the opposition is almost absolute because music and video footage stand side-by-side, the two domains separated in space and time.6

Despite the atonal and athematic principles of the work, Varèse spoke of it in terms reminiscent of programme music by listing various deserts:

“All those that people traverse or may traverse: physical deserts, on the earth, in the sea, in the sky, of sand, of snow, of interstellar spaces or of great cities, but also those of the human spirit, of that distant inner space no telescope can reach, where one is alone.”7

Here Varèse approaches Dante, since the poet is constantly engaged in a montage of the personal and the cosmic and exploring the tension between the subjective and the objective. Moreover, in his Inferno, deserts are a constant refrain: “The sand caught fire, like tinder under flint”; “Here is no hope of any comfort ever, neither of respite nor of lesser pain”; “Eyesight unaided – in that blackened air, through foggy, dense swirls – could not carry far”; “Here pity lives where pity’s truth is dead” (Inferno, XIV: 37; V: 44; IX: 5; XX: 28.). The simultaneous implosion and explosion of space finds clear expression in Friedrich Nietzsche’s verses which also concern the desert: “Many suns circle in desert space: to all that is dark do they speak with their light – but to me they are silent”;8 and “The desert grows, and woe to him who conceals the desert within him!”.9 And finally, for Jean Genet, the desert is a wellspring, in this dare and advice: “Put all the images in language in a place of safety and make use of them, for they are in the desert, and it’s in the desert we must go and look for them”.10 All this by way of posing a question that the film does not answer: does the world presented by the music precede the text of O somma luce, or is it contemporaneous with it? In the same way we can ask: is the catastrophe, which finds Giorgio Passerone sitting on a dismembered and rusted excavator’s arm, over, or is it still unfolding?

Before I turn to the cinematic treatment of Dante’s text, it is useful to look at the exact nature of the source material, because it will inform our understanding of Straub’s artistic decisions. Dating back to 1320, the Comedìa is one of the oldest texts which Huillet and Straub worked with. It is written in a proud, rich, and earthy vernacular, which Dante came to refer to as “volgare illustre” and whose standard he took up militantly against “the detestable wretches of Italy who hold this precious vernacular cheap”.11 In the enemies of the vernacular, Dante sees moral failings – vainglory, envy, and avarice – and in the vernacular he sees the very origins of philosophical friendship between author and reader. The vernacular is associated with the reign of Love (rather than Latin’s reign of Law), it is favoured by God because it is “natural (and naturally humble)”.12 As Robin Kirkpatrick summarizes, “in its power to arouse benevolence, the vernacular resembles God himself”.13

Dante’s belief in the power of the word borders on the mystical: he variously refers to the bone structure of the human face as inscribed with the letters “omo” (spelling “man” (homo), with the eyes standing in for the “o”s and the brows and nose for the “m”, Purgatorio, XXIII: 31) and of the Latin word aueio (“author”, one who can knot words with authority) as itself formed by knotting the standard sequence of the vowels: a, e, i, o, u.14 Here is a writer who takes his exploration of the power of words beyond the syllable to the molecular level of letters, yet never forgetting the syntactical, or narrative structure. It is hard to declaim or hear l. 126 of Paradiso XXXIII, “e intendente te ami e arridi!”, without feeling the full force of a phrase in which there are more vowels than consonants.15

Taking up the cause of the vernacular and the problems of how to elevate it to Latin involved theory (two unfinished treatises) and practice (his poetry). This brought about a revolution in syntax as part of a project, in Kirkpatrick’s words, “to expand the philosophical capacities of Italian writing”.16 This consisted partly of “reclothing” the Latin in the vernacular, partly in seeking “to bestow [on the vernacular] a permanence such as, by its nature, it is bound to lack”.17 This permanence, or stability of phrase, Dante found through language, as he himself put it Convivio Book One, “binding itself with metre and rhyme”.18

For the Comedìa he devises the terzina – a new, three-line verse form (in a rhyming structure of ABA BCB CDC), elegant and propulsive (a prerequisite for a narrative poem) – which can hold both reported speech and philosophical speculation. The Comedìa’s standard unit of metre is an eleven-syllable line, which concludes almost invariably with a stressed followed by an unstressed syllable.19 Each canto is never more than a mere 160 lines long (much shorter than the traditional 600 lines of Virgil or Milton) which begs the question: why does Straub, who often insists on the integrity of a text (see the Introduction to this volume), decide to cut the first sixty-six lines of the last canto? This we will return to. For the three canticles of the Comedìa (Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso), some of the language, narrative devices, and imagery are constant, while others are specific to Paradiso. All of them come into play in O somma luce and I want to touch on them briefly below.

The ‘modest voice’ is typical of the Comedìa and is a response to the ineffable nature of the poet’s experiences. It is also an acknowledgment of the natural limits of the mind, of memory, imagination, and speech.20 Throughout, Dante acknowledges that to speak is one thing and to remember is quite another. As Kirkpatrick has commented, “Though speech may be possible only where memory is active, the action of the memory cannot, it seems, automatically ensure that speech should follow”.21 It is in our nature not to see clearly (when we do see), also not to see “divine counsel” (Paradiso, XIII: 141).22 It follows that it is difficult to make reliable statements, so we should proceed with “leaden-footed” caution (Paradiso, XIII: 112).23 The eyes fail, the body quivers under the weight of the theme (Paradiso, XXIII: 64‒66), and often Dante falters and withdraws: “my pen leaps and I do not write it” (Paradiso, XXIV: 25).24

Speech is counterposed to sight. For Dante the most fundamental act of the mind is that of seeing, and for much of the poem “what is thought and what is seen are profoundly inextricable”.25 Ultimately, in the last canto of Paradiso, his experience is revealed as greater than its recounting: “from that point on my seeing was greater than my speaking” (Paradiso, XXXIII: 55).26

A courtesy which Dante seeks to foster between reader and poet is a joint intellectual and spiritual endeavour akin to the bond that Dante describes between himself and Virgil, his guide through Inferno and Purgatorio.27 Throughout Paradiso, Dante invites the reader into collaborative endeavour, seeking to engage the full exercise of all their faculties – rational, discursive, emotional, perceptual, and imaginative. Even though an anatomical and static description of heavenly order is one of his main concerns, dogma is not offered as a replacement for living faith and experience. Paradiso has a tendency to isolate statements and for the poet to interrupt himself in what Kirkpatrick has identified as self-possessed “didactic pauses”. Contrary to the previous two canticles, here the pause is not primarily an “agent of emotion”, but of understanding.28

In Paradiso, having left Virgil in Purgatory, the poet must face tests of faith and demonstrate on his own the independent virtue of his art.29 These tests are presented without suspense, or a possibility that he might fail, because the journey of the soul is complete.30 The poet has been completely exposed to the truth, having come face to face with the Light of God. It is telling that Straub excises all explicit references to the Virgin, St Bernard, and Beatrice, which feature in the first part of the canto. While Inferno and Purgatorio teem with many voices and characters, several of Paradiso’s cantos are Dante’s arias. Straub’s script features only the poet’s voice, thereby achieving maximum concentration as well as a partly de-Christianized character through a focus on natural imagery, without the allegorical scaffolding which an otherwise integral reading of the canto would impose.

The natural imagery is presented through the encounter of the poet with the variously “simple”, “living”, “lofty”, “eternal”, and “supreme” light and three rainbows. This light, which moves everything, is “self-loving” and “self-known” (Paradiso, XXXIII: 124‒26), “always what it was before” (111), an “infinite value” (81) which gives “abundant grace” (82) without receiving. However, it does receive itself as reflected in us, and it receives our “odours of praise” (as in the verses which open this text). The poet sees the face of God “painted with our likeness” (131) and feeling himself photosynthetically changing (114) knows it is impossible to turn away from this light (100‒02).31 In this glow he sees the rainbow of the Holy Trinity, which should also remind us of the Rainbow of the Covenant: the earth (“commune madre”, Purgatorio, XI: 63) is for humans and other creatures to inhabit (Paradiso, XII: 16‒18, and Genesis 9:13).

The whole text of O somma luce’s personal revelation is framed as another one of Straub-Huillet’s “to those born after”, like the philosopher’s final speech in The Death of Empedocles (1987), which addresses the People not shown by the film.32 The last line of the second terzina (72) in Straub’s script addresses the usefulness of the poet’s illumination to “the future people” or “the people yet to come”.33 This line is isolated in Straub’s instructions with a caesura before and after, which is not often found in other performances of Dante, where the performers are keen to complete the sentence which runs on for another terzina. We should not see this as a distortion of Dante, who set out to aid “the world that lives all wrong” (Purgatorio, XI: 63), by writing a public poem which, as Kirkpatrick puts it, “aims to explore the political and ethical principles on which a successful society must always depend”.34 We should also note that, rather than sinking into quietism, the final lines set in motion the dynamic and world-changing forces of will and desire.

Straub sets the text up in an alternating rhythm between mobile (panning) landscape shots and static shots of the speaker sitting “in love’s palm” (Inferno, V: 127). The division of the text creates an irregular rhythm, as the shots feature between one and four terzine.35 You can see an overview in the following breakdown of the film’s eleven shots after the music, where “P” stands for the shots of Passerone, “L” stands for the shots of landscape and the numeral represents the number of terzina: P – 3, L – 2, P – 1, L – 4, P – 1, L – 2, P – 3, L – 2, P – 4, L – 2, P – 2. The landscape shots are of varying duration and cover more or less ground depending on the speed of the pans. The widescreen frame allows Straub to cover twice the angle while maintaining a stately pace to the unfurling of the landscape.36 The first and fourth pans cover half the span (the first being the only one which Straub cuts into with the movement still ongoing), while the remaining three pans complete the full arc, and the last is the only one which also reverses, returning to the opening position. The three full arcs invite a parallel with the three rainbows in Dante’s text. The cuts correspond strictly to ends of sentences in the Comedìa as set in modern printed editions, mostly featuring one sentence and sometimes two, apart from the last cut which falls on a semi-colon. This last shot matches a change in mood, with the poet’s powers faltering as the vision slips through his fingers. Straub thereby explicitly underscores Dante’s didactic pauses, matching them with static shots of the landscape or the performer sitting silently between one verse and another.

When it comes to Passerone’s performance we have four records to draw on: the two versions of the film (shot over a period of four days) and two performances at the communal theatre in Buti which took place on the same night and were subsequently broadcast on Rai 3.37 The duration of each speech (from first to last line of speech) varies: the live performances at Buti are 7 minutes 30 seconds and 7 minutes in duration respectively. Version one and version two of the film are 9 minutes 11 seconds and 9 minutes 4 seconds in duration. The film presentation is obviously significantly slower and the pauses are given more prominence. In the theatre the speaker faces the audience head-on and in the film he is at three-quarter profile. The Buti stagings thus continue the long popular tradition of Dante being performed to the community (helping it think and feel through its life together), affirming it in an uncomplicated manner.38

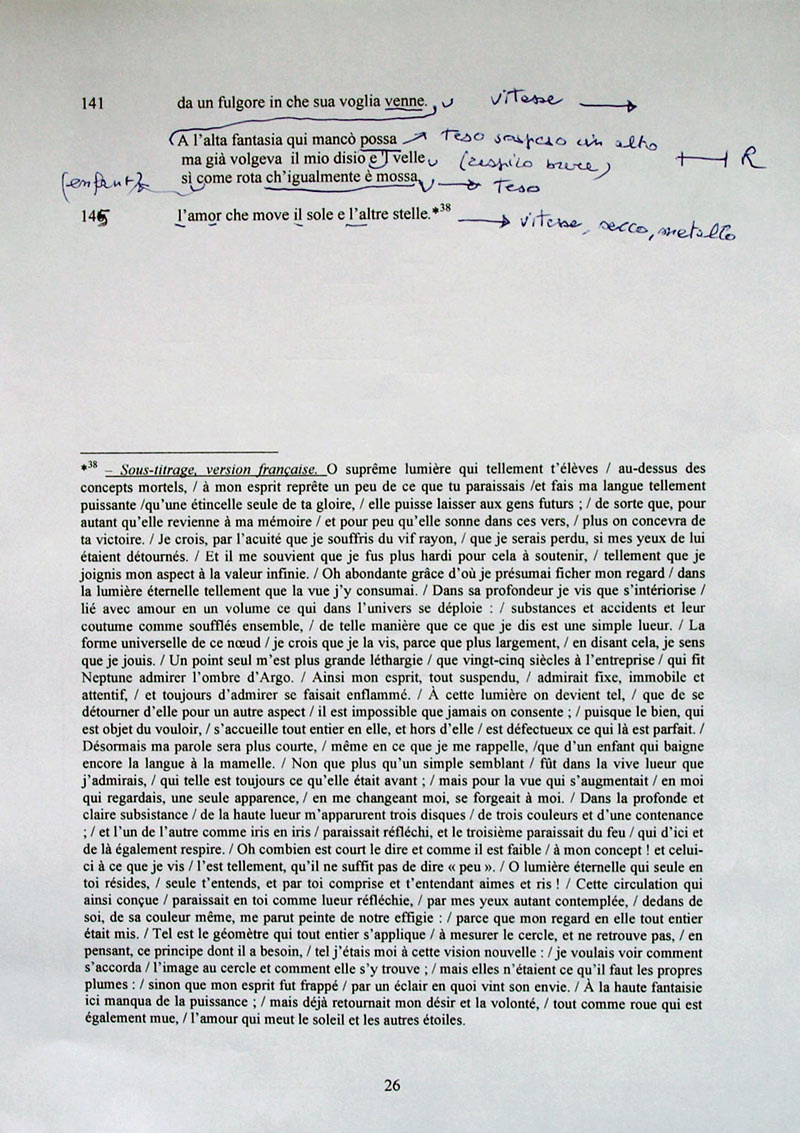

The complications arise elsewhere: “For instance, a man would be seen struggling with a text, its material nature: meter, scansion, sound and sense”, Jean-André Fieschi wrote about the films of Straub and Huillet in 1976.39 We have seen how much Dante concentrated on all the aspects that Fieschi lists. Straub and Passerone often follow the structural strengths of Dante’s design. The statements, whether full sentences or not, are marked with pauses at either end. Inserted phrases and asides (such as “of what I still remember”, in Paradiso XXXIII: 107) are grouped together and treated as incisions into longer statements. Pauses for breathing are leisurely, often before the last line in a terzina, and rarely are they short hesitations (as in A Visit to the Louvre, 2004). The Rai 3 Buti recordings show Passerone and Straub agreeing on the necessity of breathing in fully after the aforementioned Paradiso XXXIII: 126 – it ends up clearly marked with an exclamation in Passerone’s script: “Respirare!” (see Image 10 below).40 Often the last word in the line is stressed, as designed by Dante’s rhyme and end-of-line stresses. Words are mostly separated, especially when one ends with a vowel and the next begins with one. In the Buti rehearsals, Straub is seen fixing Passerone’s pronunciation of “secoli” and “foco”, concerned that they sound too French and that the first vowel in each word should be longer, truer to the measure of Italian. Straub is also concerned that Paradiso XXXIII: 123, which is another example of Dante’s modest voice and relates how feeble the poet’s speech is, is delivered by Passerone in “too prosaic” a manner. It is clear that our equivalent modern statement “my words fail me” is off the mark when attending to Dante’s intentions. Straub wants Passerone to be more emphatic, in a metaphysical sense, because of the distance of man from the divine (the Light Supreme). Likewise, the didactic, post-factum aspect must not be sacrificed to the immediate and experiential.

Occasionally, terzine, statements, or sentences are brought together, such as in Paradiso XXXIII: 93 and 94, maintaining momentum and avoiding pauses. This is an interesting passage since it is one of the most arcane and is often failed by translation. The first terzina speaks of how clearly the poet saw the all-present order of things within the light; the second terzina contradicts this by saying that this one moment brings more forgetfulness than ever in the twenty-five centuries since Neptune was startled by the ship Argo on its great endeavour to find the Golden Fleece.41 In this paradox, Dante uses the degree of oblivion (measured in centuries and relating to a myth that persists even seven centuries after the Comedìa) to speak about how much was revealed to him in an instant.42 Presence is described through absence. By bringing the two terzine together, Straub keeps the contradictions close to each other, rather than treating the second terzina as a commentary on the first. By stressing two of the three rhymes (“modo”/“nodo”/“godo” and “largo”/“letargo”/“Argo”), Straub keeps the statements together. The third, weak, emerging rhyme of “impresa”/“sospesa”/“accessa” naturally proceeds in the following statement (which is also a different shot) without any stresses on the rhyme. This is a general organizing principle of keeping the sections in the sequence set out above contained.

Straub, so fond of irregular rhythms (see, for example, Every Revolution is a Throw of the Dice (1977) and A Visit to the Louvre), ignores the commas within lines which, after all, were only introduced into Dante’s verses by the printing press, preferring instead to group words and phrases using tone of voice or equal rhythm, rather than have hesitations standing in for commas. There is a general tendency to avoid the invitation to sing the text through strict control of ascending and descending words, and a few tremolo lines, such as ll. 96 and 108.43 This last line is noted for its modesty, Dante stating that his words are as weak as the baby-talk of a suckling. It lends itself to a reduction to melody at the expense of sense.

Passerone’s gestures flow through all the four performances and play on the relationship between speech and memory, reading and reciting, since the division in the sequence listed above is also one between Passerone speaking (P) and reading from a few fluttering pages (L). All the landscape shots are preceded by him opening the script, sometimes lifting it off the ground, straightening the pages. There is thus a strict separation between the speaker’s sightline and the moving camera which performs the kind of reverence which Simone Weil also writes of: “To see a landscape as it is when I am not there... When I am in any place, I disturb the silence of heaven and earth by my breathing and the beating of my heart”.44 The unfailing sight of the gaze into heavenly light and the struggle to remember, which Dante writes of, are underscored by the gestures featuring spectacles and the fragility of the pages and the words they contain. Passerone even uses a rock to keep the pages from flying away. The modest voice finds form in a modest gesture.

In contrast stand the opening and closing shots of the performer, which both start with Passerone gazing out intently. The last shot also features two quickly succeeding gestures of poise, the first which precedes the line “not for this were my wings” (Paradiso XXXIII: 139) with the speaker leaning forward as if ready to stand up, the second with him leaning back, chest out, as if bracing for a gust of wind. Here, then, is the beginning of the work of will and desire which has to be done after the heavenly vision has passed. Both versions of the film end with a shot in distinctly overcast light – the passing of the vision is palpable, and in the first version Passerone sits poised for almost a full minute, the tension unrelenting. We would do well to remember that for Dante, the cause of Lucifer’s fall was that he would not wait for light to reveal itself progressively (Paradiso, IX: 46).

When it comes to costume, long gone are the sandals of Othon (1970) or The Death of Empedocles; the performer is dressed in everyday pale shirt and trousers which catch every change in the light, just as his scarf is caught by the wind.45 The unpatterned fabrics stand out against the burnt grass of late summer and the rust of the excavator’s arm. The red scarf teases our eye as a banner or standard would.

O somma luce dwells in the well-beloved vistas of Buti (think of the opening sequence of These Encounters of Theirs (2006) or the last shot of Workers, Peasants (2001)) with Passerone poised to recite in a quasi-amphitheatre, his back to the escarpment, facing what is probably Monte Aspro, covered in a lush canopy of trees. The poet’s aria comes up against the reality of a humble spot of Tuscany with its hints of farms, worn-out machinery, and the traces of many generations who have lived on these hills.

O somma luce emerges from the tension between these different elements: costume, setting, props, camerawork, music, editing, actor’s gestures, and actor’s speech.

This approach has parallels with what Brecht wrote about the theatre in 1930: “Words, music and setting must become more independent of one another”.46 Two decades later, he would restate this by inviting the sister arts of the drama to ‘alienate’, that is estrange, each other, rather than losing themselves in an “integrated work of art”.47 This attitude whereby contradiction and friction help to maintain freedom and integrity of various elements which enrich each other, is one shared by Straub, Huillet, Dante, and Brecht. Similarly, every question as to a pure definition of “the political” is for Straub to be answered only prismatically. To paraphrase him: there can be no political film without morality, theology, mysticism, and memory.48 He might well have been talking about the Comedìa.

Binding all these elements together is the longue durée of remembrance, moved by will and desire to fulfil our human destiny. Cornel West, speaking of the relevance of Dante to the catastrophe experienced by African-Americans in the last four centuries, centres the long duration across past and future generations: “a notion of temporality and historicity that cannot be snuffed out even in hell, and [...] the conception of the possibilities of transformation in the face of whatever kind of catastrophe is coming your way”.49 In growing deserts and among ever-multiplying catastrophes of “death, dogma and domination”, there will also be revelation.50 Here, the fate of the collective is bound to individual illumination, to knowledge, which the individual brings to the collective, and to works of art. However, as Eisenstein wrote in the depths of World War Two (in the lines which open this chapter), the paradox and scale of the catastrophe transcends individual consciousness and can only be grasped collectively. This connection between the individual and the collective is found in the content of what is revealed in the experience of illumination. Often (as in O somma luce), the experience of ecstasy, rapture, or apocalypse is represented through a tension between the raw experience and its content, be it Christian, pantheist, humanist, communist, etc. Here I want to draw on Eisenstein and Walter Benjamin (both of whom Straub repeatedly returned to). I believe they will also help us to reconcile the gradual and painstaking perfection of the soul (of the poet and the reader) which is integral to the design of the Comedìa (told in a stratified manner through the longue durée of lives dating back to Ancient Greece) with Straub’s gesture in O somma luce: a tiger leap, a sudden, almost blasphemous, short, heavenly torrent.

In Nonindifferent Nature, Eisenstein’s study of ecstasy as human experience and organized re-presentation in various artforms, we find a passage recounting the visions of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, based on a notebook the theologian forgot to burn.51 Sometimes “a symbolic image accompanies his vision, for example the image of the sun, but it is evidently only an accessory”. The passage then goes on to report Loyola’s words about the experience of the divine Being or Essence in these terms: “at first I saw the Being and then the Father, and my prayer ended with the Essence before arriving at the Father”.52

Eisenstein is fascinated that a zealot and master of psychotechnics such as Loyola would acknowledge the primacy of the universal form of ecstasy without binding it to its Christian content. This passage is mirrored by Dante’s ll. 124‒38 in O somma luce where he relates how gradually, deep in itself, the eternal light seemed to show him our human face, moving from pure light to an image. This tension between specific symbols and images which might be discovered through an ecstatic state and raw embodied experience is one which in Straub’s film is felt through the tension between the text and the bodies of the performers (human or heavenly). It is also present in the decoupling of music from figuration. The body does not exist without language, which is our link to the past, and also the organ for engaging with the world. From here it is but one small step to Benjamin’s fourth thesis on history:

“The class struggle, which is always present to a historian influenced by Marx, is a fight for the crude and material things without which no refined and spiritual things could exist. Nevertheless, it is not in the form of the spoils which fall to the victor that the latter make their presence felt in the class struggle. They manifest themselves in this struggle as confidence, courage, humour, cunning, and fortitude. They have retroactive force and will constantly call in question every victory, past and present, of the rulers. As flowers turn toward the sun by dint of a secret heliotropism the past strives to turn toward that sun which is rising in the sky of history. A historical materialist must be aware of this most inconspicuous of all transformations.”53

The river-like virtues which Benjamin lists (confidence, courage, humour, cunning, fortitude) flowing from the past, are products and refinements of Dante’s forces of desire and will, with which the poet concludes his poem, and starts again. Benjamin’s virtues of class struggle are what remain after a battle lost or won: in strata, across generations. With Eisenstein (writing two years later, in 1942), there is an understanding that a catastrophe can only be met through communion with forces which are larger than a single consciousness, but which also manifest in the individual. And just as the individual can photosynthetically change through illumination or struggle, so can “what has been” heliotropically grow in response to an illumination by the virtues of class struggle or Christianity. The past can turn to the future anew; to the past, it is of little relevance whether its future is our present or if it is our future. We find this framework in Dante, who encounters in Inferno and Purgatorio various virtuous proto-Christians who lived before Christ – for him they are imbued with the forces which follow Christ and which seem to have prepared the world for his coming. We can be illuminated differently by worlds which have ended. For Eisenstein it is the present which stretches out towards the light; for Benjamin it is the past (alive in all of us), which turns towards the sun. This is the same sun which we find in one of the poems which accompanied Babeuf’s failed Conspiracy of the Equals (Conjuration des Égaux) in 1796: “People, take hold of your rights, | The sun shines for all”.54 Just as the sun gives to all, so should the earth, and learning from the sun we can redeem the earth and ourselves in paradise on earth or in communism. The personal illumination which sets this movement in motion could be termed “communist photosynthesis”. I believe that this is the central gesture which Straub deploys in his work on Dante’s text. With reverence, yet decisive editing and organizing of the different elements analysed above, Dante’s words open out onto new worlds and opportunities for illumination.

If, however, we find ourselves in dark times, “here, too, dead poetry will rise again” (Purgatorio, I: 7). Within us dwells our illustrious vernacular language, the mover of body and spirit: “something that illuminates, and being itself illuminated casts forth its light... And this vernacular of which we speak is raised aloft in authority and power and raises its own followers in honour and glory”.55 This is the attitude which permeates every line of Dante’s poetry (and which has made it so beloved and desirable for all factions and projects: Left, Right, nationalist, humanist, cosmopolitan etc.). Straub, who devoted his life to the voicing of German, French, Italian, and English words (and their relationship to place), must be a fellow traveller. One cannot induce divine or communist photosynthesis, but one can put words into motion. Modestly and with maximum attention, this is what Passerone and Straub do with these verses. For a few minutes they dwell on the supreme moment of illumination, asking us to match the concentration of the poet and of the speaker.

- 1Sergei Eisenstein, Nonindifferent Nature, trans. by Herbert Marshall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 290. This text was written in Alma-Ata in October 1942 as part of a preface to an English edition of The Film Sense published in the same year. It was not included in that edition, but a revised version formed the preface for Nonindifferent Nature, first published in 1948.

- 2This literal translation is taken from Robin Kirkpatrick, Dante’s Paradiso and the Limitations of Modern Criticism: A Study of Style and Poetic Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), 161. I have chosen this word-for-word rendition on this single occasion for clarity. Henceforth, quotations from Dante’s text are, unless otherwise indicated, from Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, trans. by Robin Kirkpatrick (London: Penguin Classics, 2012), in the form canto: line(s). The original text reads “Nel giallo de la rosa sempiterna, | Che si digrada e dilata e redole | Odor di lode al sol che sempre verna” (Paradiso, XXX: 124‒26).

- 3The first version is 17 minutes 50 seconds long, the second 16 minutes 53 seconds. There are multiple differences between them, as they are composed of different takes. The overall structure of the film is the same.

- 4This is ground which Huillet and Straub have already covered with their adaptation of Arnold Schoenberg’s Accompaniment to a Cinematographic Scene, Op. 34 in 1973. Other filmmakers have answered Varèse’s call, notably Bill Viola in Déserts (1994) and Alain Montesse in Étude pour Déserts (1987).

- 5Quoted in Paul Griffiths, Modern Music and After (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 140.

- 6The transition from music to voice resembles the shifts between music and voice in Straub’s beloved John Ford films. These moments – in Cheyenne Autumn (1964) at approximately 33 minutes or The Searchers (1956) at around 39 minutes – build up tension musically and relay it to the voice, but by keeping the two separate, with a brief pause in between. The two different versions of O somma luce illustrate the different effects of tension and rhythm that can be accomplished by pauses between the music and the voice: almost two seconds in version one and less than a second in version two. These approaches follow through in the two versions and predictably version two is significantly shorter.

- 7Quoted in Griffiths, Modern Music and After, 140.

- 8Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book for All and None [accessed 12 March 2021].

- 9Friedrich Nietzsche, Dionysian-Dithyrambs [accessed 6 May 2021].

- 10Jean Genet, Prisoner of Love, trans. by Barbara Bray (New York: New York Review Books, 2003), vii.

- 11Dante Alighieri, The Convivio Book 1, quoted in Kirkpatrick, Dante’s Paradiso and the Limitations of Modern Criticism, 53.

- 12Kirkpatrick, Dante’s Paradiso and the Limitations of Modern Criticism, 193.

- 13Ibid., 192.

- 14From Dante’s Convivio, discussed by Eisenstein in Nonindifferent Nature, 275.

- 15The full terzina runs like this: “Eternal light, you sojourn in yourself alone. | Alone, you know yourself. Known to yourself, | you, knowing, love and smile on your own being”. The theatrical break of the line which someone like Vittorio Gassman makes (in Legge una selezione di Canti della Divina Commedia, Rubino Rubini, 1993 [accessed 6 May 2021]) works against the relentless drive of this line. As different an artist from Straub as can be, Roberto Benigni, who has spent years performing Dante, comes to the same conclusion that it is the minority of consonants which suffice in tempering the otherwise unbroken flow of vowels, and that the line should be delivered in one expiration. See Roberto Benigni: Tutto Dante — L’ultimo del Paradiso, 2002 [accessed 6 May 2021].

- 16See commentary on C. Segre in Kirkpatrick, Dante’s Paradiso and the Limitations of Modern Criticism, 93.

- 17Ibid., 85.

- 18Quoted in ibid., 85.

- 19See Robin Kirkpatrick, ‘Introduction’, in Dante, The Divine Comedy, trans. by Kirkpatrick, ix-lvi (xliv).

- 20Kirkpatrick cites Angelo Jacomuzzi in this context: Kirkpatrick, Dante’s Paradiso and the Limitations of Modern Criticism, 37.

- 21Ibid., 38.

- 22Ibid., 30.

- 23Ibid., 43.

- 24Ibid.

- 25Ibid., 16.

- 26Ibid., 39.

- 27Ibid., 75.

- 28Ibid., 155.

- 29Ibid., 82.

- 30Ibid., 123.

- 31For reasons of clarity and in order to distinguish between them, these words and phrases have been compiled from the translations of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Robert and Jean Hollander, and Kirkpatrick (see note 3). See: Dante, The Divine Comedy, trans. by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow [accessed 16 November 2021]; and Robert and Jean Hollander, Princeton Dante Project [accessed 16 November 2021].

- 32See Byg, Landscapes of Resistance, 213. As Byg states, included in Straub’s models for the ending of Empedocles are the final sequences of Alexander Nevsky (1938), Foreign Correspondent (1940), and The Great Dictator (1940), all of which feature voices addressing the People. This is based on Charles Tesson’s report of a discussion after a screening of Empedocles: Charles Tesson, “L’Heure de vérité,” Cahiers du cinéma, 394 (1987), 50. See Byg, Landscapes of Resistance, 212.

- 33See “la vita futura” from Inferno, VI: 102. These two phrases are respectively translated by Longfellow and by Robert and Jean Hollander (see note 32).

- 34Kirkpatrick, ‘Introduction’, xvi.

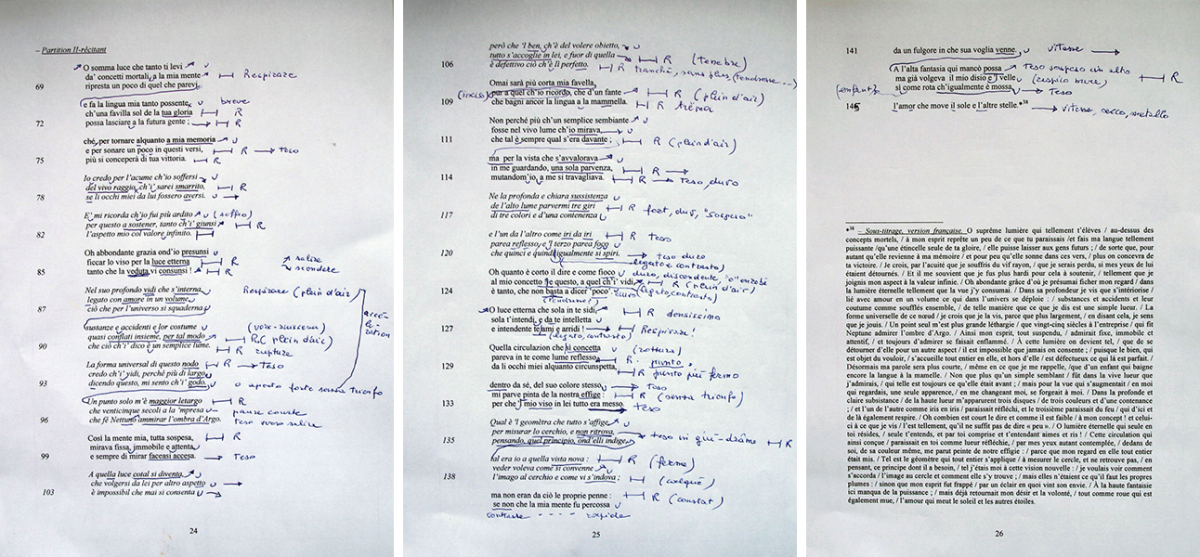

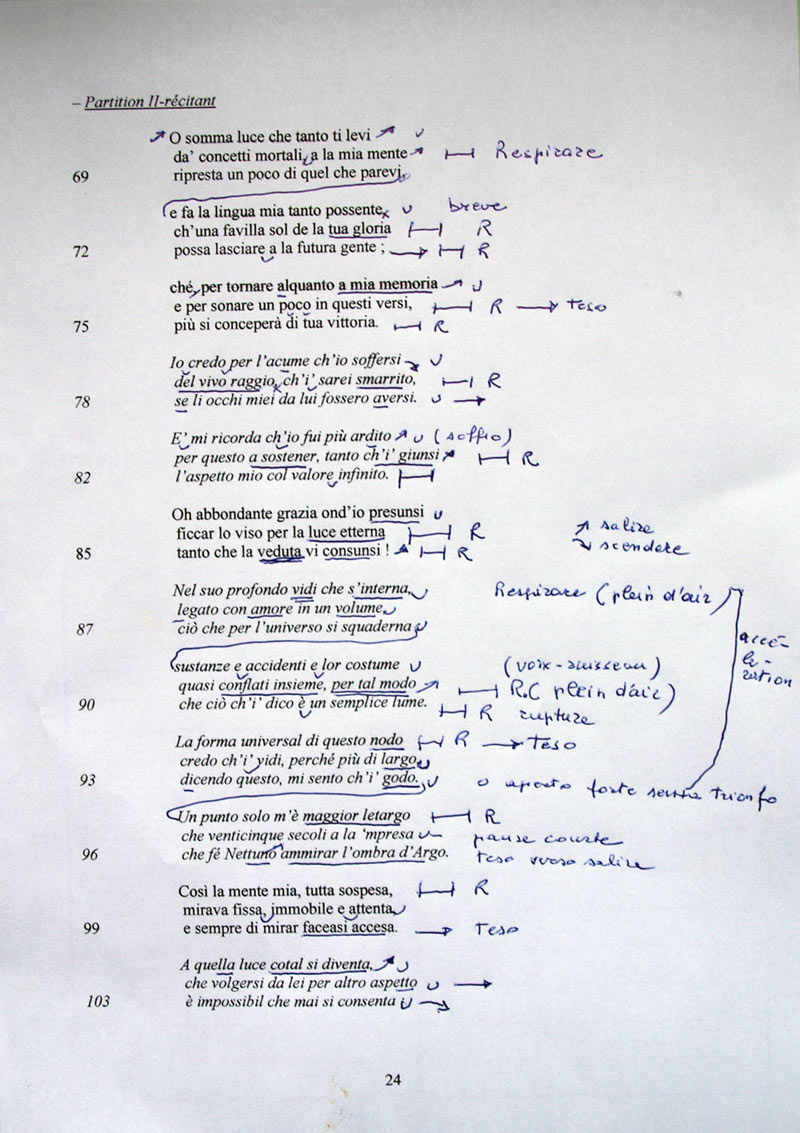

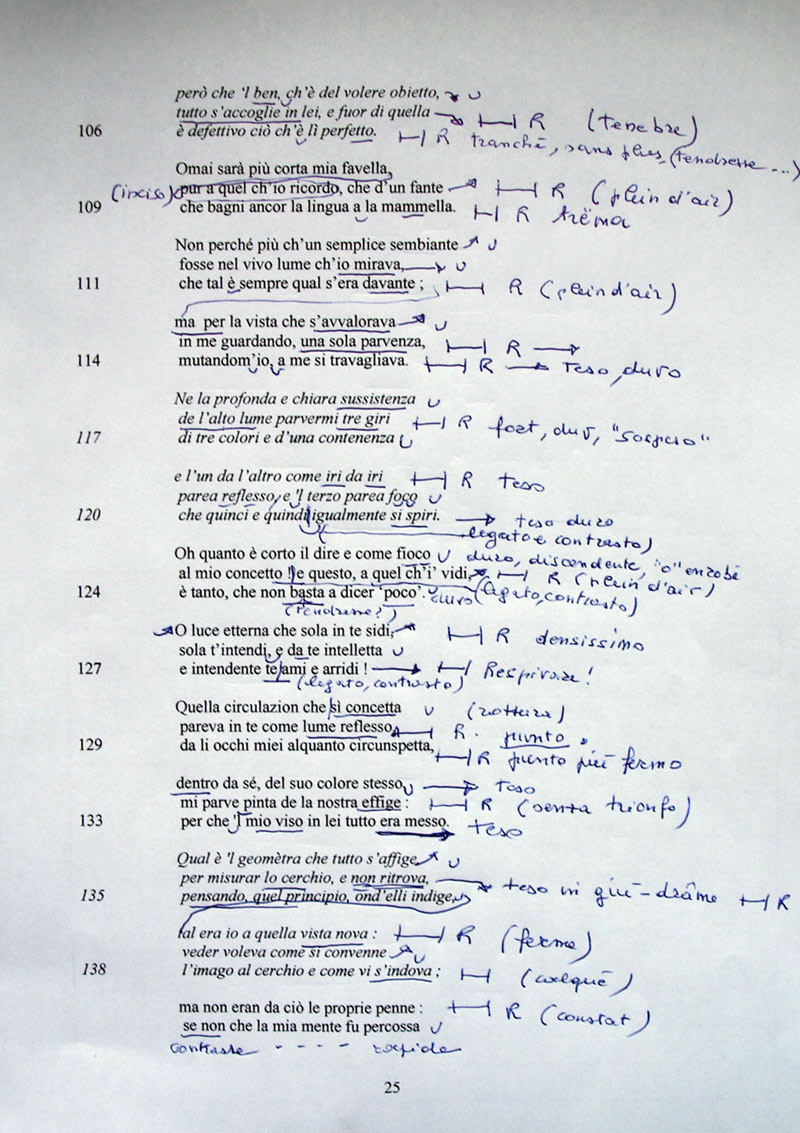

- 35Passerone’s annotated script is reproduced here [accessed 28 January 2022].

- 36After five decades of filmmaking, this is the first time Straub has explored the potential of a widescreen frame.

- 37In their Buti work, Huillet and Straub started with the theatre performance and then proceeded to the film shoot a few weeks later; this is the one case where the sequence was reversed.

- 38Carmelo Bene, for example, did a reading of Dante to commemorate the first anniversary of the Bologna massacre in 1981: Rino Caputo, “Dante by Heart and Dante Declaimed: The “Realization” of the Comedy on Italian Radio and Television,” in Dante, Cinema, and Television, ed. by Amilcare A. Iannucci (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 213‒23 (216).

- 39Fieschi, “Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet”.

- 40See here. The line numbering in Passerone’s script does not always match the conventional numbering used in this article.

- 41Of course, Neptune was not around at the time, it would have been the Greek god Poseidon. This is just one of many examples of Dante’s passion for the layers and palimpsests of history, shared by Huillet and Straub.

- 42See George Ferzoco, “Changes,” in Vertical Readings in Dante’s Comedy, ed. by George Corbett and Heather Webb, 3 vols (Cambridge: Open Book, 2015‒17), III, 51‒69 (67‒68) [accessed 8 March 2021].

- 43For indications of ascending words see the arrows before and after the first line of Passerone’s annotated script, and the end of l. 76 for an indication of a descending enunciation.

- 44Weil, Gravity and Grace, 42.

- 45Huillet and Straub have spoken about the many aspects of this shift away from period dress between their early and late treatment of Pavese in Emmanuel Burdeau and Jean-Michel Frodon, “L’Important est l’éventail,” Cahiers du cinéma, 616 (2006), 36‒39; “Encounter with Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet: Quei loro incontri,” trans. by Ted Fendt [accessed 8 March 2021].

- 46Bertolt Brecht, “The Modern Theatre is the Epic Theatre,” in Brecht on Theatre, ed. by Willett, 33‒42 (38).

- 47Bertolt Brecht, “A Short Organum for the Theatre”, in Brecht on Theatre, ed. by Willet, 179‒205 (204).

- 48Albera, “Sickle and Hammer, Cannons, Cannons, Dynamite!,” 109‒11.

- 49African-American Interpretations of Dante’s Divine Comedy, hosted by Trinity College, 4 October 2020 [accessed 10 March 2021].

- 50Ibid.

- 51Eisenstein Nonindifferent Nature, 165, 181‒83.

- 52Ibid., 172‒74.

- 53Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, 246. Translation corrected to include “confidence” [Zuversicht].

- 54“Peuple resaississez vos voix | Le soleil luit pour tout le monde,” Charles Germain, ‘Chanson des Égaux’, 1796; ‘Song of the Equals’, trans. by Mitchell Abidor [accessed 11 March 2021].

- 55Dante Alighieri, De vulgari eloquentia, quoted in Kirkpatrick, Dante’s Paradiso and the Limitations of Modern Criticism, 64.

I am indebted to Lia Mazzari for a translation of the Buti audience discussion and rehearsals. I am grateful to Tag Gallagher for an extensive and generous polemic. Ian O’Sullivan and Eleanor Watkins from the BFI Library very kindly tracked down the Charles Tesson article during the library’s closure to the public due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Images (1) and (8) Jean-Marie Straub, O somma luce (2010, courtesy of BELVA Film).

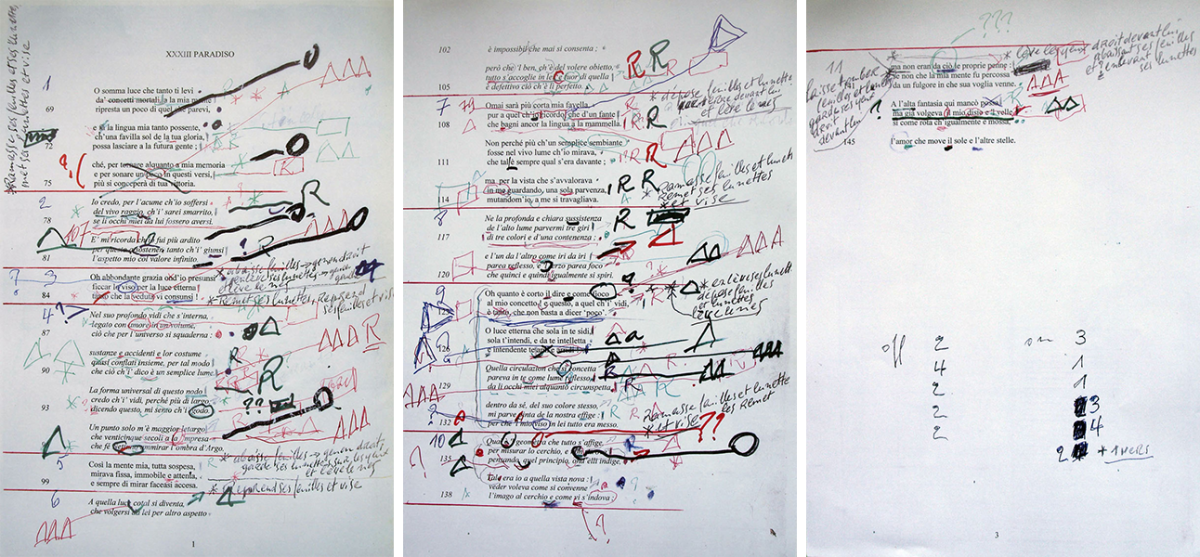

Image (2), (3) and (4) Jean-Marie Straub, annotated script of O somma luce.

Images (5), (6), (7), (9), (10) and (11) Giorgio Passerone, annotated script of O somma luce (© Giorgio Passerone, by permission).

More detailed representations of both the annotated scripts can be found on this page.

This article was first published in The Cinema of Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, eds. Martin Brady and Helen Hughes, Moving Image, 14 (Cambridge: Legenda, 2023).