Pourquoi le film se déroule-t-il en Belgique ?

Alain Resnais: Ce n’est pas un hasard. Je ne suis pas Belge, mais c’est un pays qui m’a toujours, comment dire, auquel j’ai toujours été sensible: Magritte, Delvaux, la lumière, une certaine qualité de lumière, le surréalisme, la tradition fantastique belge, etc. Et puis, [l’écrivain et scénariste] Jacques Sternberg est Belge. Et il y a beaucoup de sa mythologie personnelle dans le film. Jean Ray, l’auteur des Aventures De Harry Dickson, ce film que je rêve de faire depuis douze ans, était Belge. Je ne le savais pas. Et puis, la Belgique, c’est la première frontière que j'ai franchie. En ’46–47... c’était les films américains que nous ne pouvions pas voir à Paris. Les ‘serials’ qui arrivaient à Bruxelles, nous allions les voir dans une salle située Place de l’Etang Noir. Toujours le fantastique... Tout cela m’a marqué. La Belgique, pour moi, c’est l’imaginaire...

Why does the film take place in Belgium?

Alain Resnais: That’s not by accident. I’m not Belgian, but it’s a country that has always – how do I put it – to which I’ve always been sensitive: Magritte, Delvaux, the light, a certain quality of light, surrealism, the Belgian tradition of fantasy, etc. And then, [the novelist screenwriter Jacques] Sternberg is Belgian. And a lot of his personal mythology is in the film. Jean Ray, the author of The Adventures of Harry Dickson, a film that I’ve dreamed of making for 12 years, was Belgian. I didn’t know it. And then, Belgium is the first border I crossed. In ’46-47… it was for American films we couldn’t see in Paris. Serials that came to Brussels, we went to see them in a theater in the Place de l’Etang Noir. Always fantasy… It all left a mark on me. Belgium, for me, is the imaginary…

Interview with Resnais at The Film Desk (original source unknown)

Erik Martens: U bent ook in België komen filmen.

Alain Resnais: Ja, Je t’aime, je t’aime werd gefilmd in België: in Oostende en Brussel. En voor een deel ook Providence [1977], een film die zich eigenlijk in New England in Amerika afspeelt, maar waarvoor we locaties zijn gaan zoeken in Antwerpen, Brussel en Gent. De beelden die we zochten moesten geïnspireerd zijn door de Italiaanse Renaissance, door de traditie van de Europese architectuur. Ik wist dat ik daar in België een equivalent voor kon vinden. Daarnaast bracht ik in België ook geregeld bezoekjes aan mensen als [Henri] Storck en aan een aantal Belgische acteurs die ik waardeerde. Het viel me ook altijd op dat in de Muntschouwburg opmerkelijke stukken werden gecreëerd. Men wachtte geen twintig jaar om een Amerikaans stuk op te voeren. Nee, er waren altijd veel redenen om naar Brussel te komen. Het is natuurlijk jammer dat men er zoveel oude huizen heeft afgebroken. De stad heeft veel van haar sfeer van mysterie en avontuur verloren.

Had u contacten met schilders, met de surrealisten bijvoorbeeld?

Ik heb het geluk gehad ooit Magritte de hand te kunnen schudden na een vertoning van L’année dernière à Marienbad. Hij was heel vriendelijk. Hij vertelde me dat de film hem interesseerde en helemaal in zijn lijn lag. [Alain] Robbe-Grillet en ik hadden bij het tot stand komen van het scenario vaak aan Magritte gedacht. Voor het nooit gerealiseerde project van Harry Dickson had ik Paul Delvaux gevraagd decorontwerpen te maken. Ik had zijn toezegging toen al op zak. Ik houd trouwens ook van de andere Delvaux: Un soir, un train, dat is een goeie film.

Erik Martens in gesprek met Alain Resnais1

This footage shows Resnais shooting the film in Ostend while we hear him answering the questions of longtime RTBF film journalist Sélim Sasson (in French, 12’).

“Resnais is the master-cutter of ‘60s cinema... Resnais is the anti-Ophuls. Ophuls used camera movements to turn space into time, to waltz himself through Vienna 1900, or Paris à la belle époque, in a fond remembrance of time past. Resnais twines past and present around each other so that neither can escape the coils of the other... Resnais’s title promises naive romantic fervor, but the repetition proves ominous... It’s a science fiction tragedy in comic strip images. Everybody thinks of [Henri] Bergson, and no doubt they’re right. But if Resnais, Marker (La Jetée) and their friend [Walerian] Borowczyk (Renaissance, 1964) are all obsessed with time, there may be another reason too: a profoundly Marxist sense of history as the nightmare from which man is trying to awaken. People weren’t then ready for this quiet mixture of science fiction with a love story as subtle as anything in Rohmer and Rivette. But with Marker’s La Jetée and Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris [1972], it constitutes a holy trinity of meditations on the horrors of eternal life.”

Raymond Durgnat2

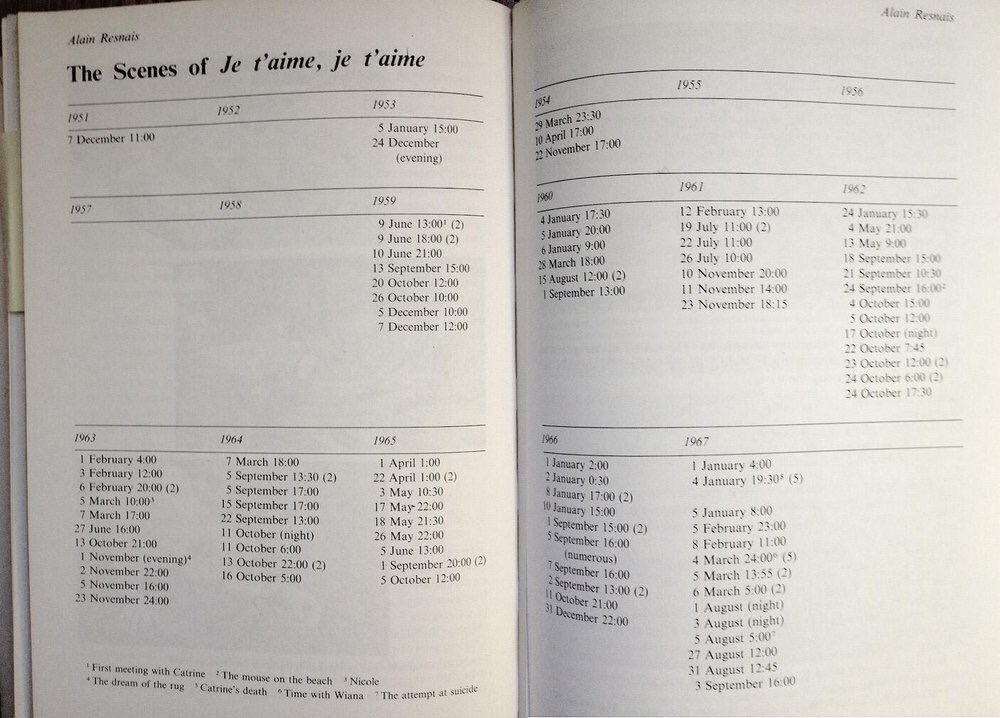

“For anyone with even the mildest interest in the particular cinematic concerns of Alain Resnais, Je t’aime, je t’aime should be thoroughly irresistible. [...] It’s an editor’s film par excellence. [...] The découpage of the film, which seems complex at first viewing, is actually among the simplest in Resnais. The film has only about 334 shots (as opposed to almost a thousand in Muriel ou le temps d'un retour). [...] In a way, this is Resnais’s most practical, least theoretical film. Its provenance lies in his experience in the 1950s as a film editor. Anyone who has had the experience of discovering the power of the editing table to analyse the rhythms and mysteries of reality will understand Resnais’s premise immediately. [...] Je t’aime, je t’aime is, quite simply, Resnais’s masterpiece of realistic montage. [...] Je t’aime, je t’aime – the doubling of the title mirrors the doubling of times and sentiments in the film – is a glistening mosaic... Joyceian poetry out of the strange language of Flemish, the film is also studded with puns and wordplay, much of it difficult to translate.”

James Monaco, who also made this timeline / cheat sheet of Je t’aime, je t’aime3

- 1Erik Martens, “Film is emotioneel wisselgeld. Gesprek met Alain Resnais,” Streven: cultureel maatschappelijk tijdschrift, 15 oktober 1999.

- 2Raymond Durgnat, “Pacific Film Archive Programme Notes,” In Henry K. Miller (ed.), The Essential Raymond Durgnat (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 159.

- 3James Monaco, Alain Resnais. The Role of Imagination (London: Secker and Warburg, 1978). The source of the timeline is pp. 138–139.