The Gallardo family lives off a strip of land on the edge of the jungle. In fragile equilibrium, this goes well for generations until the big economy and politics reach their lives. A radiography of a country through portraits of individuals and families. Lav Diaz and his extreme cinematographic approach - films of five to ten hours, a limited number of shots, little camera movement - has long divided minds, but now he is almost unanimously counted among the most important directors of the moment.

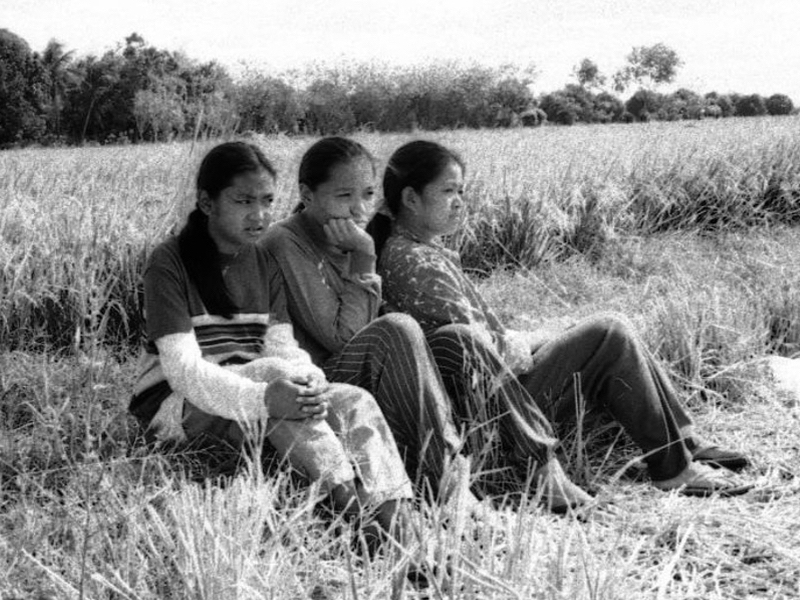

“Diaz’s aesthetics blend the national-popular praxis of the Bandung era with the realist film ethics of French theorist André Bazin. An archetypal scene is one framed as a long shot and lasting the duration of a long take. Diaz’s mise en scène displays the materiality of the physical environment; he stages movement as powerless human bodies traversing through immense space. Land, forest, water, rain and volcanic clouds simultaneously engulf all matter and figure historic destruction. Detritus of past conflicts sediment in soil layers; forest vegetation grows rampant over anonymous, slain bodies from past struggles; the coneshaped Mount Mayon is a mass murderer. A shot may begin with a panoramic view of a paddy field, a forest, a shoreline or a hill. The recorded pro-filmic space seems depopulated at first, until we catch a glimpse of a tiny figure moving on the furthest plane. The duration of the shot corresponds to the length of time it takes that person to walk into the foreground and out of the frame. Diaz often uses the long take to mark the duration of the hard yet purposive labour of peasant and underclass characters. Activities such as farmers planting, miners digging or vendors pushing a cart shape the tempo of scenes and sequences. Further, the extended duration of each shot gives time for bodies to pause from physical activities and to accrue gestural intensity. This staging of gesturing bodies in desolate landscapes is one example of the ways in which Diaz’s aesthetics blend the theatrical mode of performance with realist filmic space.”

May Adadol Ingawanij1

Alexis Tioseco: This is both your first and your latest film.

Lav Diaz: Yes

How has your perspective of cinema, how has the way you see your work, and what you are trying to do with it, changed since you started and are now finishing this work?

It changed a lot. When I was starting I was still groping and looking for my aesthetic. Through the years, while I’ve been searching, it’s evolved. Now, I’m very clear with my aesthetic now. If you compare that to a growing person, in 1994 I was child, in relation to cinema, my aestheticism. But now I’ve matured, I’ve found it; I know what I’m doing. My vision is clear. I know what I’m doing now; I know what the purpose of my art is. It’s very clear now.

Do you think that will affect this work in the effect that some parts will be from the person who was searching for his vision, and some parts will be made by the director that has understood what he’s looking for?

Yeah, it’s like that. The very idea of Ebolusyon is like that; the search, the study; the examination. Just like Batang West Side. It’s still an extension of that perspective; that search for answers. It’s the same with my cinema. It evolved and it involved, and I know what I’m doing.

Lav Diaz in conversation with Kerrine Goh2

- 1May Adadol Ingawanij, “Long Walk to Life: The Films of Lav Diaz,” Afterall 40 (Autumn/Winter 2015): 102-115.

- 2Kerrine Goh, “Lav Diaz And The Insane Struggle For Evolution,” ASEF CULTURE360, 22 Sep 2009.