Bio-filmography of Chantal Akerman

From 1950 to 1995

Born in Brussels on 6 June 1950

- Her maternal grandfather left Poland in 1918 and settled in Brussels. He was a very religious Jew. His wife was a painter, a transgression difficult to accept. She never returned from the concentration camps and her work disappeared in Germany.

- Her mother was deported to Auschwitz. Chantal was deeply influenced by her grandfather, who lived with her parents and ensured that the family home remained in the shadow of the synagogue.

“There are portraits of my grandfather at home, with his beard and everything.” (Interview with Jean-Luc Godard, Ça cinéma, issue 19)

- Her father had a workshop for leather and pelts. He became a shopkeeper. He would have liked Chantal to go into business.

1957

Birth of her sister Sylviane. Married, she now lives in Mexico.

1958

Death of her grandfather.

- She first attended the Jewish school, then the school on Rue Léon Lepage and finally the Lycée Émile Jacqmain, where her future producer, Marilyn Watelet, was also a pupil.

- She remained at the lycée [high school] until the third year. Her best memory: learning to write and writing.

“I have a relationship with writing that is certainly as strong as with cinema.”

1965

“I was in Brussels, I didn’t like cinema at all, I thought it was for idiots, all they took me to see was Mickey Mouse or things like that... and then I saw Pierrot le fou and I had the impression that it spoke of our times, of what I felt. Before, it was always The Guns of Navarone. And I didn’t give a damn about those things. I don’t know, but it was the first time I had been moved by a film, and I was moved violently. And no doubt I wanted to do the same thing with films that would be mine.” (Interview with Jean-Luc Godard, Ça cinéma, issue 19)

- Shoots her first shot, her mother entering a large building and opening the letterbox.

1967

Attended the Knokke-le-Zoute Experimental Film Festival with Marilyn Watelet, created by Jacques Ledoux, curator of the Royal Belgian Film Archive [current CINEMATEK]. One of the films she saw there was Wavelength by Michael Snow. “But I rejected a lot of films because I was looking for a story, sensations, feelings... What I remember is lying on the floor and sleeping through the whole festival. There’s a time for everything.” (Interview with Michèle Levieux, Écran 76)

1968

Saute ma ville (short film)

Without this decisive revelation, Chantal Akerman would probably, she says, have become a writer. But since cinema had become part of her life, she applied to INSAS (Institut national supérieur des arts du spectacle)1

where she would remain for a short time.

“Nobody took me seriously at that school. They just laughed at me. I realised that I had to make a film to earn any respect at all. So I went to work for a bank, just long enough to finance a short film, which I shot when I was 18. It was shown a lot at festivals...” (Interview with Alain Riou, Nouvel Observateur, 28 September 1989)

Due to a lack of money, the film remained stuck in the laboratory for two years. It was seen by chance by André Delvaux, who spoke enthusiastically and decisively about it when it was programmed by Eric de Kuyper on his BRT programme, De Andere Film. This was to be the start of a long friendship with Eric de Kuyper, a film theorist and historian as well as a filmmaker himself. As for André Delvaux, whom she went to see to thank him, he gave her advice on how to get into the modest but effective film support scheme run at the time by Émile Cantillon.

- “There’s a whole problem in relation to the image for the Jew: you’re not allowed to make images, you’re in transgression when you do, because they’re linked to idolatry. That’s why I try to make a very essentialised cinema, where there are no sensationalist images.” (Interview with Jean-Luc Godard, Ça cinéma, issue 19)

- Chantal Akerman moves to Paris.

“The real reason why I live in Paris is, in the end, very independent of whether or not I like the city. In a way, I didn’t want to live at home, but I didn’t want to be too far away. For that, Paris was the ideal place. As a Dutch speaker, I might have chosen London. As a French speaker, I chose Paris. At the age of 18, when I packed my bags, the literature lover that I was also thought that it was the city where people write the most. I very quickly realised that this was not true. People write everywhere. But even as a child, I had this rather silly idea that one day I’d write novels in Paris in a maid’s room...” (Interview with Louis Danvers, Weekend-l’Express, 6 September 1991)

1969

Six-month internship at the Université internationale du théâtre. Writes two screenplays, Une histoire d’amour and L’enfant mort. Play based on Vincent van Gogh’s letters to his brother: “A studio rooted in life itself.” Assistant director on three feature films directed by Yvan Lagrange: Naissance, La famille, Une leçon de chose.

1971

L’enfant aimé (short film)

“It’s a film that never satisfied me. I applied very abstract ideas to it about refusing to edit as a way of manipulating the spectator, without taking into account the fact that opting for the sequence shot formula is very nice, but you have to prepare and time this kind of shot tremendously. I let it happen and it didn’t work. (Interview with Jacques de Decker, Le Soir, 14 January 1981)

- She travelled to Israel, then left for New York with Samy Szlingerbaum, a childhood friend. She made a living from odd jobs. Among other things, she worked as an usher in a porn cinema. She met Babette Mangolte, who shot her first films and introduced her to many new things. With her, she also entered the movement of Yvonne Rainer, Michael Snow and other New York experimental filmmakers. She frequented the Anthology Film Archive. She watched the films and discovered a territory of freedom. She would say that it was a fantastic period in her life.

1972

Hotel Monterey (feature film)

“The only place where I could feel a bit at home is New York. Because over there, everyone comes from elsewhere... Personally, I don’t like belonging to a specific place: it keeps my mind awake and allows me to understand and feel what people who are stranger than me in terms of language or skin colour are going through.” (Interview with Louis Danvers, Weekend/l’Express, 6 September 1991)

“When I first saw the Monterey Hotel, I was interested, shocked. If I’d done anything straight away, it would have been a reportage. But I spent six months working and thinking about the hotel. It’s all about recreating a certain reality through the cinematographic language. It works on different levels: time, space, colour, light, duration and rhythm. (Interview by Marie-Claude Treilhou)

1973

La chambre (short film)

Le 15/8, co-directed with Samy Szlingerbaum (medium-length film)

Hanging out Yonkers (feature film)

“This might have turned out to be a magnificent film. I was asked to do it by an organisation in New York that dealt with the rehabilitation and reintegration of young offenders. But as I wanted above all to work on the soundtrack, and I only had a cassette recorder, it didn’t work out. I only kept the rushes.” (Interview with Jacques de Decker, Le Soir, 14 January 1981)

1974

Je, tu, il, elle (feature film)

“I worked as a temp to earn 5,000 to produce Je, tu, il, elle. As luck would have it, I found some blank film abandoned in a corridor.” (Interview with Alain Riou, Nouvel Observateur, 28 September 1989)

“I made this film with three people and we had to do everything ourselves.” (Interview with Godard)

“I made this film in ’74, based on a text written in ’68. At the time I wrote it, I was the same age as the character and had the same sort of problems. If I had shot it then, I would have made a film about an anecdote, whereas the space of six years made a mise-en-scène possible, and my use as an actress was part of that mise-en-scène. And yet, every time I see the film again, the image – my own image – that it sends back to me makes me uncomfortable. I don’t seem to have anything in common with this character who is so out of touch with society, so desperate, yet who takes one action after another, with a kind of secret decision, a silent despair bordering on screaming. I have a busy life and I seem to have gone over to the adult side with a smile, but I think that in all of us, there remains a resonance of that scream of a moment, which we stifled to play the game of society.” (Royal Belgian Film Archive, unsigned interview, not situated.

1975

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Brussels (feature film)

The first version of the script was called Elle vogue vers l’Amérique. The role of Jeanne interested Delphine Seyrig, but Chantal Akerman rewrote the script and completely transformed the story.

“I was tossing and turning in bed, worried. And suddenly, in a single minute, I saw Jeanne Dielman in its entirety.” (Nouvel Observateur, 28 September 1989)

The film was made with the help of the film department of the French Community of Belgium, which allocated four million Belgian francs. Delphine Seyrig remained a close friend of Chantal Akerman until her death.

When the film was released, a masterly article by Louis Marcorelles appeared in Le Monde on 22 January 1976. It was entitled “Nouveau cinéma comme nouveau roman” and ended with the sentence: “Certainly the first feminine masterpiece [chef-d’œuvre au féminin] in the history of cinema.”

- Creation of Paradise Films with Marilyn Watelet. In 1978, Marilyn Watelet, who until then had been a script girl at RTB,2

gave up this job to devote herself to the production company Paradise Films, which primarily produced films by Chantal Akerman.

1977

News from Home (feature)

“It’s a project I did without writing, like Hotel Monterey or La chambre. I wasn’t worried about it, because it’s a more conceptual project that started with an idea, a shock, an image I had of New York, and the sounds that were my mother’s letters.” (Interview with Godard, Ça cinéma, issue 19)

“The only thing that usually works for the spectator is identification with the character. But in my film, there’s no hero, no classic narrative. It works elsewhere, on rhythms, on pulsations, on the gaze. One image leads to another. It’s like music. You follow notes and here, you follow images. There’s only one thing you can do, watch and listen, and it challenges you as a viewer. It’s a film about time, space. I’m showing a certain New York, which is not the New York people are used to seeing. (Interview with Martine Storti, Libération, 20 June 1977)

1978

Les rendez-vous d'Anna (feature film)

This was the first film to be produced by a major company, Gaumont, and was therefore made within a classic production system, even if the budget remained modest when compared with mainstream commercial investments.

“Anna’s journey through Northern Europe is not a romantic one, nor is it one of learning or initiation. It is the journey of an exile, a nomad who owns nothing of the space she crosses... The people Anna meets are all on the edge of something. It wouldn’t take much for them to topple over ... they are vaguely aware that the values on which they have built their lives are shaking ... they wonder about happiness. What kind of happiness and how? I think we’re at the end, at the end of something, and that we’re about to start something we don’t yet know anything about. I’m like the characters in the film. What might happen, I don’t know...” (Cahier Atelier des arts, 1982)

1979

Chantal Akerman wrote the adaptation of two novels by Isaac Bashevis Singer, The Manor and The Estate. She went to Los Angeles to set up the production. The budget was estimated at five million dollars. She was unable to raise the money and the project was abandoned.

“Basically, I’d always managed to do what I set out to do, and then I hit a brick wall. I talk about it lightly now, but it was very hard.” (Libération, 29 October 1982)

1980

Dis-moi (short film)

First work for television. From then on, Chantal Akerman alternated between feature films and commissioned works, to which she gave the Akerman touch, the latter being no less personal than the former.

1982

Toute une nuit (feature film)

“The film begins with a very hot night, crossed just before dawn by a violent storm, and ends in the morning, a morning of very bright sunshine, with a sky washed in a soft blue. The first – and longest – part, the night, takes place in a very tense atmosphere, one that precedes major storms, to the rhythm of the beating heart. It is made up of a series of fragments, almost all of which have to do with quivering, romantic or sexual tension, and always with feelings. These fragments are like pieces of intensity. Finally, the storm breaks ... and then everything in the houses stops. The second part of the film is much shorter. It’s dawn, the only moment of respite before the day begins... all tension has disappeared, it’s dead calm. With the dawn comes the third part of the film. The activity resumes with the awakening. Normally, as if the night, with its emotions, had been forgotten. During the night, we see a host of different characters, couples, families or loners of all ages... At dawn, we find only a few of them. Three or four. And in the morning, hardly any more. Some we would have seen again at dawn, others we would have lost since the night.” (Atelier des Arts, 1982)

Hôtel des acacias (medium-length film)

Raymond Ravar, then director of INSAS, asked Chantal Akerman to return as a teacher to the school she had so hastily left as a student. She ran a directing seminar there, and wrote the screenplay Hôtel des acacias in collaboration with Michèle Blondeel. It was made with the students and was the first draft of Golden Eighties.

- Also at INSAS, the first seminar devoted to Chantal Akerman under the direction of Jacqueline Aubenas. It led to a publication (out of print) with papers by Thierry de Duve, Eric de Kuyper, Benoît Peeters, Françoise Collin and others.

1983

Les années 80 (feature film)

“Between a script and a film, there’s a whole territory to cross. Les années 80 is the time spent in that territory. A love battle with reality and its elements: the actors, the singers, the dancers, bound and constrained by a story, in a set, under a light crossed by music. How, between the still unrepresentable script and its future representation, are the different elements of reality gradually organised into a film? How do you go from reality to fiction?” (Foreword to the press kit)

1984

L’homme à la valise (feature film)

Un jour Pina a demandé (feature film)

J’ai faim, j’ai froid (short film) (episode of Paris vu par... vingt ans après)

Family Business (short film)

New York, New York bis (short film)

Lettre d'un cinéaste (short film)

One of the years that separated Toute une nuit from Golden Eighties. But between the two, Chantal Akerman never stopped working, accepting television projects, writing and living.

1985

Golden Eighties (feature film)

Chantal Akerman took four years to put this project together. On 23 September 1985, Louis Skorecki published a virulent article in Libération entitled “Qui veut empêcher Akerman de tourner?” (“Who wants to stop Akerman from filming?”) The producer’s energy did the rest. This was the first film she shot entirely in a studio in Paris, where the setting of La Toison d’Or in Brussels was recreated.

“First of all, I wanted to make a comedy. A comedy about love and commerce. Burlesque, tender, frenetic. A comedy where the characters would talk quickly, move quickly and constantly, driven by desire, regret, feelings and greed, crossing paths without seeing each other, seeing each other without being able to reach each other, losing each other only to find each other again. As the film unfolds, the plots will become tighter and tighter, the feelings will become more exasperated, and the characters will move faster and faster... It will be like a mad machine that goes into overdrive, only to suddenly regain its composure in the last frame, when, for the first time, we finally catch a glimpse, in the light of the setting sun, of the outside world, of other life.” (Cahier des Ateliers des Arts, 1982)

- Encounter with cellist Sonia Wieder-Atherton, whose influence will be decisive in the development of the musical score of Chantal Akerman’s films.

1986

Letters from Home (feature film)

Le marteau (short film)

Rue Mallet-Stevens (short film)

Journal d’une paresseuse (short film)

1988

Histoires d’Amérique (feature film)

“I always wanted to make a film about the Jewish diaspora. In my mind, it was a vast, ardent, romantic Gone with the Wind. Then I thought about a more interior form, but I didn’t want to make an abstract film either. I’m not sure how the present form came about. No doubt it was a way of communicating with what my mother went through, which left her unable to speak throughout my childhood, to the point where I was sick myself.” (Interview with Alain Riou, Nouvel Observateur, 28 September 1989)

“It just so happened that La Sept asked me to make a documentary about the writer Isaac Bashevis Singer. Once I got to New York, I realised that I had something else to convey. The producers agreed that I should change my project [...]. I found the themes for the monologues in Yiddish newspapers. I invented other stories, rewrote jokes found in Freud’s books...” (Interview with Katia Berger, Journal de Genève, 21 October 1989)

Les trois dernières sonates de Franz Schubert (medium-length film)

Trois strophes sur le nom de Sacher (short film)

1991

Nuit et jour (feature film)

“About ten years ago, I found myself in Joseph’s position [one of the characters of the film]. I was ashamed, mortified, I thought it made a mess of everything. At the time, I made a few notes. When I was putting my house in order, I found them again and I said to myself: “I’m going to write a story with all this, a story that will be beautiful and clean. I wrote it in one go, without knowing where I was going.” (Interview with Fernand Denis, La Libre Belgique, 28 September 1991)

Contre l’oubli (short film)

Chantal Akerman is one of thirty filmmakers who took part in the film produced for Amnesty International’s thirtieth anniversary. They will all be broadcast on French channels (except TF1) on cable, M6, TV5, CFI and RFO.

1992

D’Est (feature film)

Chantal Akerman was asked by Kathy Halbreich, curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Boston; Susan Dowling, producer at the WGBH; and Michael Tarantino to make Bordering on Fiction; Chantal Akerman’s D’Est, a multimedia installation devoted to the unification of the European Community. These initiators were joined by Bruce Jenkins and Catherine David, then curator at the Galerie nationale du jeu de Paume. The film, which was shown at the festivals of Locarno and Florence, quickly became a cult documentary.

“I’d like to make a long journey through Eastern Europe while there’s still time. I’d like to film everything there, in my own documentary way that borders on fiction. Everything that touches me. Faces, bits of streets, passing cars and buses, stations and plains, rivers and seas, streams, trees and forests. Fields and factories and more faces, food, interiors, doors, windows, food preparation. Women and men, young and old, passing or stopping, sitting or standing, sometimes even lying down. Days and nights, rain and wind, snow and spring. And more faces. And all this slowly changing, throughout the journey, the faces and the landscapes... I would like to record the sounds of this land.” (Film press kit)

Hall de nuit

A play first performed at the Théâtre de Léthé in Paris, directed by Amahi Desclozeaux.

“I want to write plays because I’ve always loved writing – my film scripts were already very well written – and because I’ve always loved the theatre. I like the constraints that this genre imposes and I also like the freedoms that it allows.” (Programme for the play Le déménagement, Brussels, 94)

The text Hall de nuit was published by L’Arche (50 pages, 1992) and received writing assistance from the Fondation Beaumarchais.

Le déménagement (medium-length film and play)

The play was directed by Jules-Henri Marchant at the Petit théâtre du Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, from 13 May to 3 June 1994, with Luc Van Grunderbeeck in the role of the monologist and Alex Basselet for the performances in sign language.

1993

Portrait d’une jeune fille, fin des années 60 à Bruxelles (feature film)

1994

Death of her father.

1995

Un divan à New-York (feature film)

A comedy scheduled for release in December 1995. A major challenge in Chantal Akerman's career.

D’Est (museum installation)

Will be shown in October at the Galerie nationale du jeu de Paume in Paris, and in December at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. It will travel to the USA, Germany, Spain, etc.3

- 1Brussels film school founded in 1962 by Raymond Ravar, André Delvaux and Paul Anrieu [translator’s note]

- 2RTB: Radio-télévision belge, now RTBF, the autonomous public broadcasting company the French-speaking community of Belgium.

- 3This text originally appeared in 1995, which explains the future tense in this last piece. Sabzian is currently working on a second part of Chantal Akerman's biofilmography, from 1995 to 2015. This text will appear soon.

Image (1) from Saute ma ville (Chantal Akerman, 1968)

Image (2) from L’enfant aimé ou je joue à être une femme mariée (Chantal Akerman, 1971)

Image (3) from La chambre (Chantal Akerman, 1973)

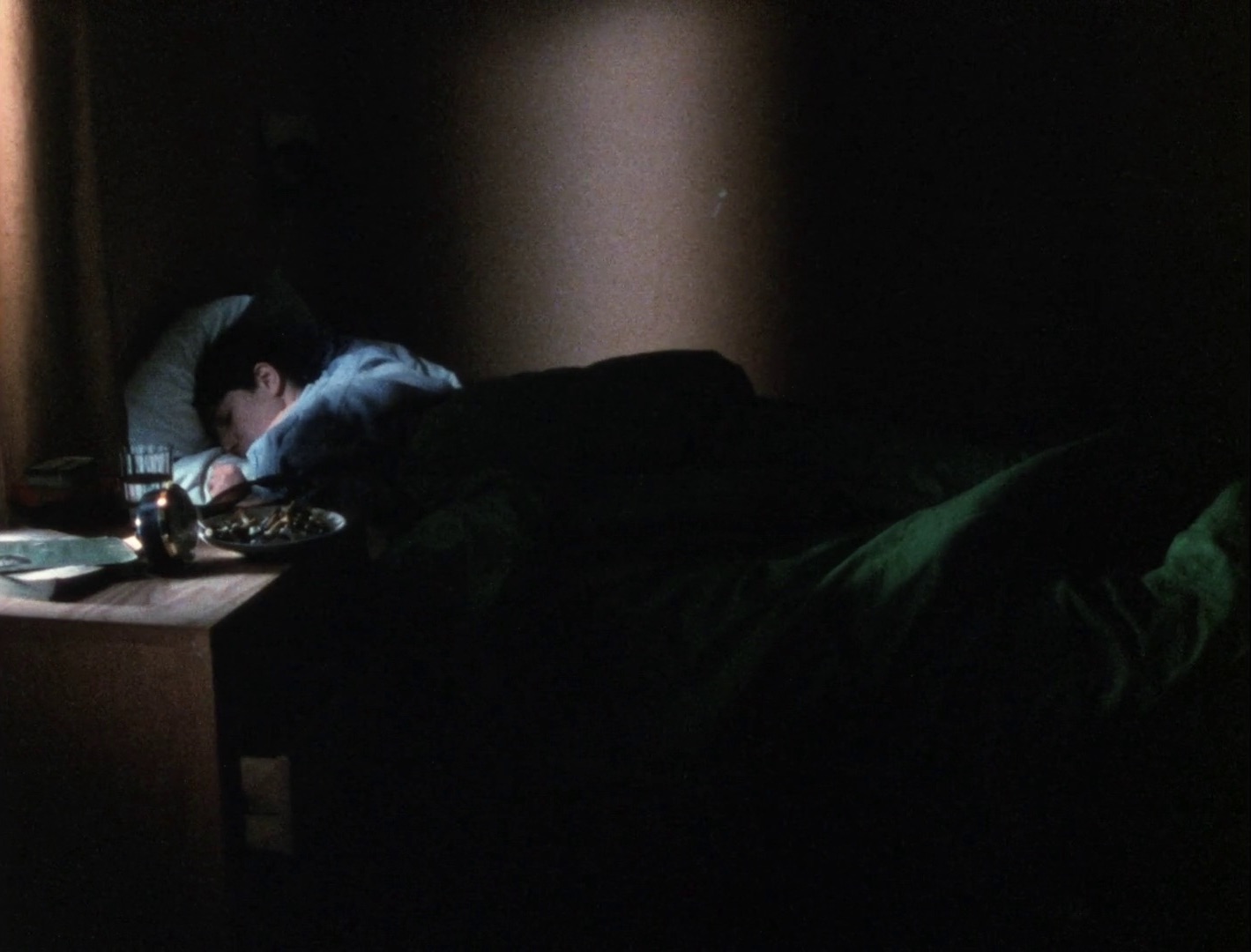

Image (4) from Je, tu, il, elle (Chantal Akerman, 1974)

Image (5) from L’homme à la valise (Chantal Akerman, 1984)

Image (6) from Portrait d’une paresseuse (Chantal Akerman, 1986)

Special thanks to the Chantal Akerman Foundation.

Originally published in Hommage à Chantal Akerman (Brussels: Communauté française de Belgique, Wallonie-Bruxelles, 1995).