Carl Theodor Dreyer

Spiritual Gentlemen and Natural Ladies

“People say that women contributed but little to the discoveries and inventions of civilisation, but perhaps after all they did discover one technical process, that of plaiting and weaving. If this is so, one is tempted to guess at the unconscious motive at the back of this achievement. Nature herself might be regarded as having provided a model for imitation, by causing pubic hair to grow at the period of sexual maturity so as to veil the genitals. The step that remained to be taken was to attach the hairs permanently together, whereas in the body they are fixed in the skin and only tangled with one another. If you repudiate this idea as being fantastic, and accuse me of having an idée fixe on the subject of the influence exercised by the lack of a penis upon the development of femininity, I cannot of course defend myself.“ (Freud)

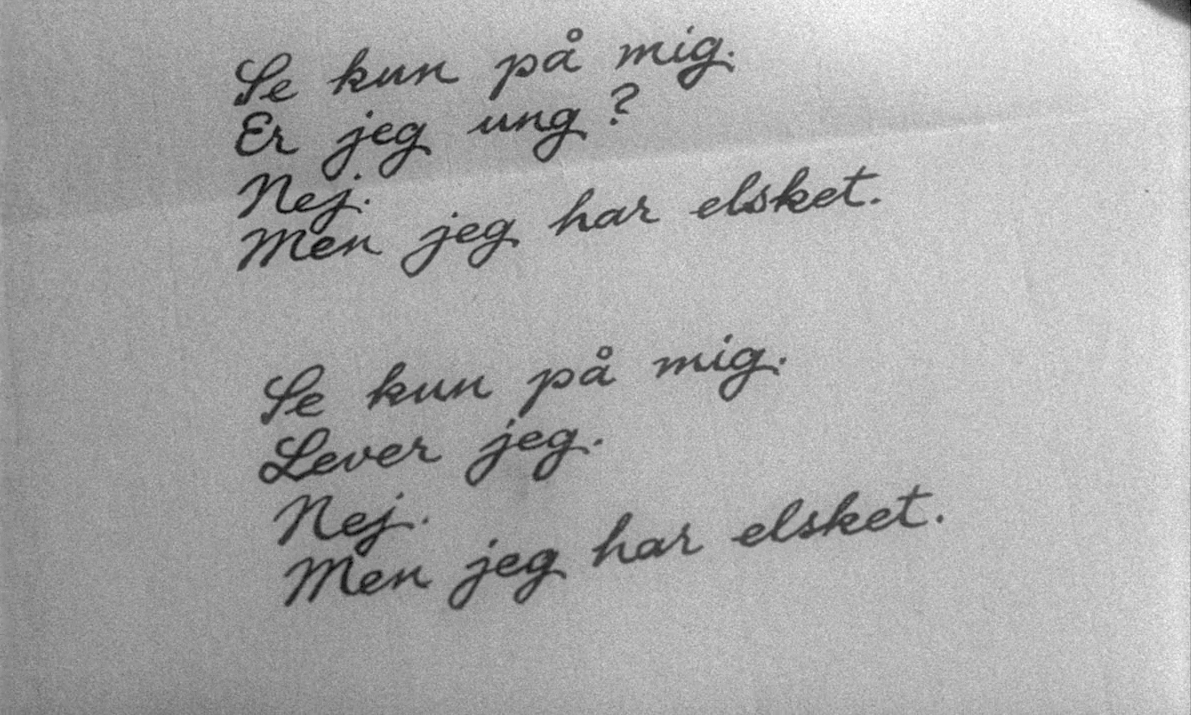

There should be many more images on this page, so many that the writing would only stumble forward. Photographs that pierce the text, just as in Dreyer’s films suspended objects, mirrors, pictures and windows make holes in the walls. Of secular and ecclesiastical courts, of all-male councils sitting in judgement upon child murderesses, witches and saints; of fathers giving daughters in marriage as they see fit. Photographs of texts, too, which rigidly and violently stem the flow of film images again and again: decrees, certificates, instructions on how to drive a stake through a vampire’s heart at midnight. And poems, love poems in Gertrud (1964), that sing of what existence can only afford within the realm of poetic freedom.

Then there are images, often of stretched-out men’s arms over which women have hung wool so as to better wind it into a ball. Another shot: a bride and groom eating from a pot with two spoons chained together. And then there is the table and chequered oilcloth in The Word (1955), on which Inger rolls out her pastries, and on which she will later lie to give birth to her dead son. Finally, the last image from Dreyer’s last film: a white door in a white wall, which Gertrud, white-haired, half-shade, has closed behind her. She could no longer bear the men’s cold talk of duty, honour, work, law and passion. The loftiest notions, the most general and the emptiest ones according to Nietzsche, “the last smoke of evaporated reality”. (It would be foolish to dispense with male authority altogether, the crazier they are and the greater misogynists the better).

Gertrud had taken the terms literally and wanted to fill them with life. She became troublesome. Like Michael Kohlhaas, she did not understand that laws and reality are opposed to each other, are two inherently different registers.

![(2) Ordet [The Word] (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955) (2) Ordet [The Word] (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955)](/sites/default/files/Dreyer_01.png)

A Room Like a Sieve

Dreyer said he particularly liked white walls. There were white walls in almost all his films. We see white walls appear in Vampyr (1932), when the rhythmic loads of flour coming down slowly become a dungeon, a trap, a grave for the old doctor. With Dreyer, white walls consist of a multitude of luminous, transparent particles. Reality becomes transparent; contours and solidifications dissolve. The material develops a life of its own – Vampyr owes its light quality and resulting structures to a copying error. Vampyr should be seen after Michael (1924), the film adaptation of Herman Bang’s novel of the same name, the story of a master painter with a flaunty lifestyle. The nineteenth century, and with it idealism, closes its last window and lies down to die.

In Michael, there is one shot of nature, a landscape, that threatens to suck up everything around it. In Vampyr, its consequences are realised. The film images have relieved and dissolved those of the ending nineteenth century.

It is irrelevant how conscious Dreyer was of contributing to the transition to a new era. His films are shaped by it. They are passages, in-between worlds. You clearly notice how moved his characters are because he lets the actors move slowly. And the camera, too. You have plenty of time to listen to the words, to explore the spaces. Dreyer said that he lets language appear in close-up and that he makes theatre adaptations in order to take the theatre beyond itself by means of the cinema.

Rather than communication of meaning, his dialogues are modulations, musically overdetermined, a multitude of accents. In echoes, the end of language is expressed – in Vampyr and in The Word, where the mad Johannes quotes the Bible in a monotonous voice, repeating sentences and words. And the moaning of the men in Gertrud. Its beginning, its crude form, is found in Day of Wrath (1943), the old woman’s childlike cries that penetrate from the attic down into the parsonage when the officers catch her so that she can be tried as a witch.

In between lies the realm of language, of order, of spoken order. Where what looks clear, unambiguous and verifiable is permitted – the world of interrogations and procès-verbaux – where the ever same sentences must be used to administer justice, to keep order. Dreyer said of Joan of Arc (1928) – its sequence of close-ups making it the purest, most cinematographic of all Dreyer’s films – that it was a film about language, about language as a means of torture, about linguistic terror.

![(3) Ordet [The Word] (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955) (3) Ordet [The Word] (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955)](/sites/default/files/Dreyer_08.png)

Too Much Honour

Dreyer’s representatives of the word make up a curious sect. The proclaimers of the word are spiritual dignitaries, pastors, judges, family tyrants, homosexual foster fathers and word artists, poets. Thou Shalt Honour Thy Wife from 1925: the story of a head of house whose backbone is removed and broken by three women: his mother, his old nanny, his wife. Dreyer brings forms into view that make clear the underlying structures that generate them. At first you don’t notice that you still have some sympathy left for this patriarch, who is a total bastard. It’s his sad face that gives it away. He is the great outcast when all other family members conspire. His exclusion is not a result of his disgusting behaviour. He is overwhelmed by his father position.

The film concerns the oft-cited role behaviour whereby men become fathers against their will because they are born into symbolic systems that they are unable to fulfil. Dreyer’s fathers, the guardians of order, are crushed by their own prestige, by what their status, their social position in the broadest sense of the word, demands of them: the father in The President (1920), the father in Day of Wrath, who has to be a father for both his family and his community. When the two fathers in The Word quarrel about their children, whose marriage is thwarted by the different faiths of their parents, you can hear two mutts yapping in the background.

In the name of the father, not as the real fathers they are, they justify their behaviour. The symbolic order shapes the real. And Gertrud shirks both by having no name carved on her gravestone, neither her father’s nor her husband’s, only amor omnia. She wants to be herself at last. She has already done away with the mirrors given to her by the men who loved her.

Gertrud is the invention of a man, the invention of two men: the film was made after a play by Hjalmar Söderberg. Gertrud is a statue, a monument, like many women in Dreyer’s films. Her demands are as absolute as the contours of the film, its spaces and the gestures of its characters are hard and angular. Her demands are too idealistic, which is how you recognise the detour via the men. But occasionally you hear the long dresses rustle, a certain intimacy setting in. And then she goes to Paris to study with Charcot, Freud’s teacher. This real name in a fictional context forces a breakthrough comparable to that of the nature image in Michael. The long-valid order now cracks. With reality, another dimension emerges.

The Return of the Repressed

What emerges was never dead, merely covered; invisible through the sediments of deliberate conventions. The age-old that still changes is The Parson’s Widow (1920). The aged pastor’s wife who, because the benefice is tied to her person, ends up with a windbag of a lover in her fourth marriage, shakes off all that life had covered her with. From the object of exchange, from the object among objects to which she is attached, as she says, because they make up her life, she finds her way back to the feelings of her youth. To the astonishment of those around her, she leaves the house more and more often to go out to the grave of her first husband, with whom she was connected by feelings she rediscovers in the swindler couple.

The virulence of the subject is reinforced by the film’s comic force, which tugs vigorously at the foundations. The end of the film, however, is terrible, cruel in the way only Dreyer films can be cruel: the old woman dies, the young woman slips into her clothes.

Even the most terrifying of mother figures, the old Merete in Day of Wrath, oblivious and more pontifical than the Pope when it comes to defending the laws of the male world, has her weak moment and steps out of the frame. When she finds her son dead, a very different apparition appears next to the figurehead of the pastor’s house, resembling the old good witch whose condemnation to death at the stake she had found just.

A 1926 paper by Freud states that female sexual life is a “dark continent” for psychology, which comes across all the darker because there is no other English expression to be found anywhere else in the text. He does not so much mean, as Wilhelm Reich later did, the danger that women would threaten authoritarian ideology if they were officially granted the right to sexuality. Rather, Freud meant that femininity escapes representation: sublimation. That female sexuality does not obey the laws of repression and that its suppression requires a stronger kind of censorship.

Anne, the young witch in Day of Wrath, is married to a much older man. The most perverse and poorest of pastors, who by virtue of his position has taken himself a young wife after the death of his first. From his previous marriage, he has a son the same age as the young wife he has never touched. When the son appears, the system gives way: successive generations begin to intermingle. Anne is only a weak link in the chain. Nature breaks through the superpositions of culture. “The confusion of generational succession is cursed in the Bible as in all traditional laws ...” You can feel the danger slowly rising: a harmless game of hide-and-seek at the beginning to surprise the old pastor is how the cheating begins, the Fall of man.

Anne admits to having witchcraft powers during the interrogation, and sees her love betrayed by the man who takes back his place in the paternal order. The chain closes again. Where there was difference and contradiction, there is harmony again. A boys’ choir eases the young woman’s death by fire with the “Dies irae”.

![(5) Vredens dag [Days of Wrath] (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1943) (5) Vredens dag [Days of Wrath] (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1943)](/sites/default/files/Dreyer_05.png)

Inside/Outside

The abyss that briefly yawned, the disorder that spread and the endangerment of the laws all point to the ground on which order rests. In French, “maître” is still synonymous with “lawyer”. In Michael, “master” refers to the master painter whose mastery comes to an end because nature strikes. Close the windows, the painter says to his servant, and with that the last trace of the outside world disappears from his studio. The appearance of nature in Michael is linked to the appearance of the woman; she is natural, says Baudelaire, i.e. hideous. Dreyer shows that the nature of women indeed allows for all forms of masquerade; in Michael, Nora Gregor as Princess Zamikoff is a real scarecrow.

With Dreyer, looking behind things does not mean searching for ideal depths. His beyond is not, as with Fritz Lang, the underground, the corridors and caves and dungeons beneath the earth. It is on a level with the visible. Decisive is not what is behind the images but rather what becomes visible as a blind spot in those images. The beyond of Dreyer’s films, which he often hides behind historical fabrics and garments, is this world, but repressed and censored. I build houses in which no one wants to live, laments the mad Johannes in The Word, taking two candlesticks with burning candles and putting them in the window. Gertrud could say the same.

Dreyer’s mystical themes often seem to be completely at odds with the realist nature of his medium. It is true that Dreyer sometimes behaves like a sorcerer, like Anne in Day of Wrath, when she tries out her supernatural powers and is surprised and shocked to find that they work. Dreyer uses film to wake the dead. But you have to go one step further to follow him. With his films, he not only shows reality, but also the symbolic nature of reality. He makes the symbolic orders and their restrictions visible. He changes the usual connection between sign and idea. By insisting on objects with the density of bodies, he protests against the idea of the total translatability of everything into everything. For him, there is something that stops the cycle of images and symbols. “Labour”, says Marx, “is not the only source of material wealth; it is its father, and the earth is its mother.” When Inger has died in The Word, the father consoles his son by saying that she is in heaven, but the son says, inconsolably, “But I loved her body too.”

The centre of Dreyer’s films does not appear directly. He marks its edge. The images are only scraps of the infinite, the unformed, the possible, hieratic and rigid, to demonstrate their limitations. In Dreyer films, you can never identify with just one character; heroes and villains do not exist. The struggle is more cosmic, but not ahistorical. With him, orders collide, or rather order with disorder. One should not be deceived by the often quietist endings of his films. They provoke anger. And, when you think about it, the miracle at the end of The Word, the raising of the dead, is really the triumph of disorder.

An event beyond any possibility of interpretation or context. A zero point, another blind spot, a gap in the chain of causality. When Freud began to describe and theorise the unconscious, he could only conclude that the conceptual apparatus of the existing sciences was failing. That we depend on the big Other, which for the time being can only be conceptualised in negative categories.

Watching Dreyer’s films today, one often thinks they are out of the world. When Gertrud premiered in Paris in 1964, at Dreyer’s request, the premiere audience was deeply disturbed. Their embarrassed diagnosis was total greying. The film was different from what they had expected, different from the memory of Dreyer’s earlier films. “Quite natural”, said Dreyer, “are the actors. They speak and walk in a very natural rhythm.” Once you’ve seen them, they keep coming back.

Originally published as ‘Carl Theodor Dreyer. Geistliche Herren und natürliche Damen’ in Süddeutsche Zeitung, 9-10 februari 1974. © Brinkmann & Bose Publisher Berlin, Germany

Images (1), (4) and (6) from Gertrud (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1964)

Images (2) and (3) from Ordet [The Word] (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955)

Image (5) from Vredens dag [Days of Wrath] (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1943)