The Partition of Anne-Marie

“As the adventure is not being two.

The adventure is being alone.”

– Hélène Bessette

At the edge of Anne-Marie Miéville’s films, even before the story wriggles its toes, with the first breath recorded by the camera, a resounding gust of air initiates a threshold at which to place the spectator. Strictly in the present. One foot outside, one foot inside. We could be under the illusion that we’re attending the making of the film (sometimes even the prelude to the shooting itself) and that what goes on there, the dramatic moment, is also ours. The “moviegoer” (Walker Percy) and the filmmaker find themselves in the same time, that of observation. Transforming daily life into a sound space and into lyrical time is a complex undertaking, a poetics: to watch life is to transform it into the present. To declaim life in order to grab hold of its rhythm. It’s also to renew a certain continuity and to proclaim a beginning, a middle, and an end. We can see Anne-Marie Miéville on French television in 1984, on the programme Spécial cinéma, alongside Jean-Luc Godard and in front of Daniel Schmidt to talk about Prénom Carmen, for which she was the scriptwriter: she embodies the story’s enthusiasm and integrity. Godard says that Anne-Marie’s enthusiasm brings to the table what he lacks, “a feeling of continuity,” he says, “the script’s nervous system and skeleton which later give ideas of flesh and skin to the director”. You need to mark, he adds, while saying that he doesn’t know how to do it, a “straight or curved line with a beginning, a middle and an end”. From her first films onward, without counting the ones she co-directed with or wrote and edited for Godard, Miéville commits questions to film in the form of shots, questions asked to cinema, about the expression of origins, small children, music, thought, singing. Saying yes, saying no. Dancing, walking, having an abortion, giving birth, handling the whip, putting together bouquets of flowers, questioning, ironing, answering, shutting up. Cinema gives answers, pierces the silence we assume, or splits the chaos we can also assume, both patent links to the origins. Piercing the silence with language and music doesn’t accompany the characters, but delivers them to us. We attend incarnations of sound. One step before the image, or right next to it.

How can I put this? Each shot by Miéville is a silent recording of what is, of what happens wherever the filmmaker rests her feet and gaze; that is to say, whenever she pricks up her ears and makes us perceive the world the way she hears [entend] it – in the double sense of understanding [comprend] it and of recording it in her sharp, refined, both sensitive and peremptory way of listening. We say: le silence se fait (a retraction, something animal, without a subject in the form of a personal pronoun); we also say: faire silence, avoiding the definite article, passer sous silence, agir en silence. As for Miéville, elle garde le silence.1 To see better, or “to make us see” (“donner à voir” – JLG). Not to understand better. The magnificent light, the voices and faces strive towards discovering, in the sense in which the sea uncovers the rocks at low tide, a form/matter/metal shaped in silence (silence is gold) and making the film’s beginning simultaneous with the intensity of our perceptions. From this raw form/matter of Anne-Marie Miéville’s cinema, harmony and lyricism arise and establish themselves, along with an old disorder, that of souls. Eloquent souls rather than ghosts from silent movies. The characters, always first a woman, children, express themselves acutely. They fall prey to the mass of the living, but they’re never victims: they’re actors; they’re the haunted ones. “Once across the bridge” (Murnau), it’s not male souls but female souls who come to meet us, souls that have taken their time, at their own pace, less prompt than the bodies (in the travel sequence from Nous sommes tous encore ici, the actor Jean-Luc Godard notes that his soul has difficulty following the rhythm of his body). These souls or spirits go to Anne-Marie Miéville, who in her turn will shelter them and be their host. The filmmaker often films doorsteps, windows, transparent separations between outside and inside. You have the feeling she opens her door with parsimony or (and) apprehension. The souls, the actors, live in comfortable rooms of houses on the lake, illuminated by bay windows, big lamps with indirect lighting and vases filled with bright-coloured bouquets standing on impeccable tables. They are interpreters, voices, souls disguised as well-dressed silhouettes, as comedians. Not necessarily welcome, they are invited. To leave, to pass by or to stay. They are there, still, here, or elsewhere; yet when they’re absent, deprived of field and frame, you wouldn’t know how to reach them, nor where to find them. They’re not in books, but they’re inspired by reading. You have no idea how they’ve made the journey and where they come from. How did they get here from the pages, from their beds? Which door have they slammed shut behind them? We won’t know. Or only if someone like Arthur the sailor (Jacques Spiesser) in Après la réconciliation, the potential lover for every woman who grants him a kiss on the riverbanks, talks about his sea voyages, a drink in his hand, his head bent, leaning on the piano: “I can tell you about the spiritualization of the body, how to free yourself from vulgar needs, such as food, sleep, except alcohol of course”; a tale established throughout this endless conversation, like a round dance (not far from Max Ophüls’s and Arthur Schnitzler’s La ronde), providing the film with choreographic and acrobatic movement. The body is never far away, nor is bitterness.

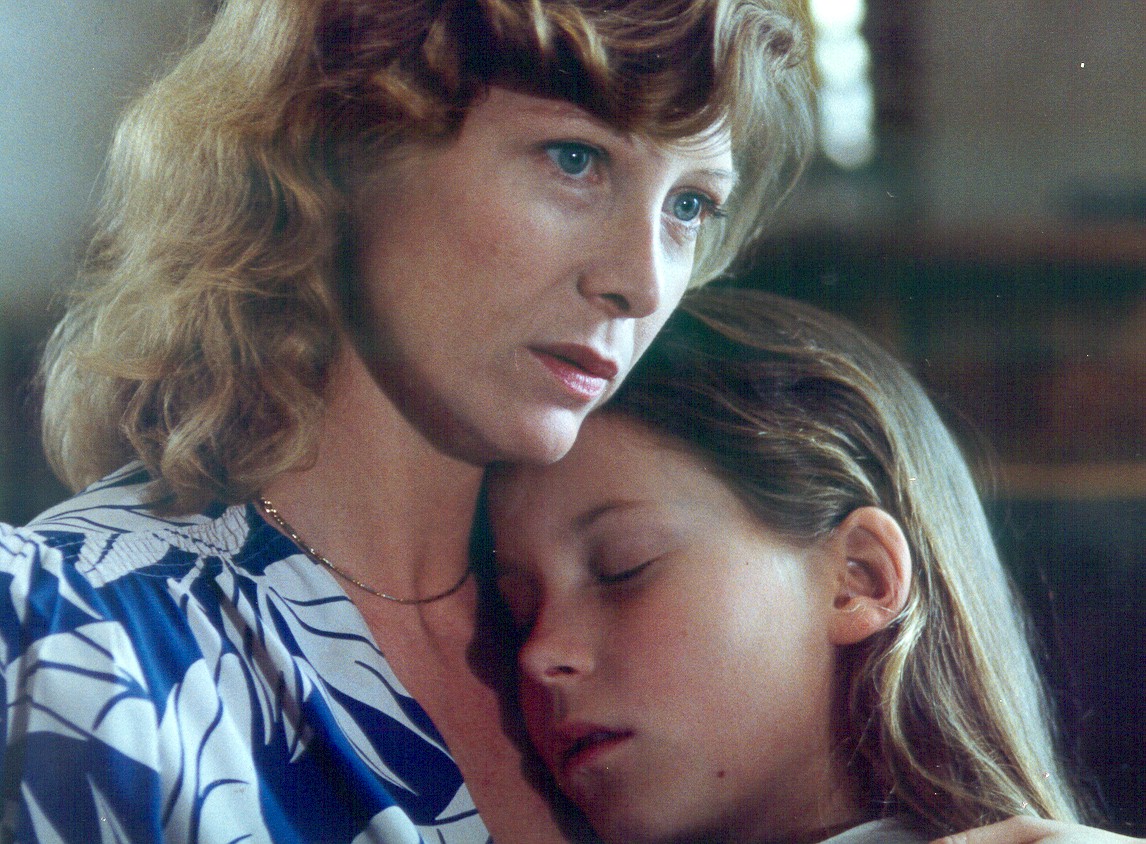

Making the journey, the physical path, is in fact a testing of others. In her short film Le Livre de Marie, Miéville presents an eleven-year-old girl, Marie (Rebecca Hampton), whose presence is very demonstrative. When taking the train to meet her father, her so-called classmates talk down to her and molest her, evoking her parents’ parting. Above all, the child wants silence from those who surround her, her parents and her fellow students. They all exclude her from their bickering, all of them locked in their own resistance to the other. They argue like partners without even leaving the slightest role for the child. She wants a story about herself to look forward to. “Can you tell me about when I was little?” she asks her mother, played by Aurore Clément, the both of them in the bath, two naked bodies in the same skin. Marie, the one before this little one, the mother of God, the one of the prayer, is then multiplied. Le Livre de Marie, directed to be paired with Jean-Luc Godard’s Je vous salue, Marie, is like the gift of a childhood for Joseph’s wife, Mary. The child who’s multiplied bends her body and her voice into an abundance of gestures, declarations and movements. Marie chants her existence, makes herself heard with La La La, with a chanted version of Für Elise, with a mimicked military march and with a dance as infinite as a fainting fit, on Mahler’s Symphony No. 9, almost like an intense and momentary blackout: the transition to another body. Mahle(u)r in her! Marie refutes, contorts, addresses the missing. In a sequence at the beginning of the film, she mimics a class teacher, articulating a Baudelaire poem, as if she is dictating it to an invisible, entirely imagined reverse shot. She alone lives on. Her words aren’t heard, she interrupts her reading and instructs her invisible and mute pupils to shut up. We see a reverse shot on her small, empty bed. She cries: “Silence! Silence, I said!”

Every time we enter a film by Miéville, we experience the feeling of an urgency – to separate? To lift ourselves out of everyday routine, as the mother in Le Livre de Marie says? To be among sisterly and brotherly souls, in a sort of eclipse of the world? We also experience the physical sensation of the filmmaker’s presence, of the exact (imaginary) location from which she perceives. Her character, her step, her gaze. Her cinema is inseparable from a kind of moving forward, a path. From the start, here and now, the spectator is thrown into a luminous and melancholy world, quite diurnal, aggressive, deliberate, lucid and also full of fantasy: the filmmaker gives us the power to discern something in it. In this case, that which divides us. We are faced with compositions of forms, of rhythms – in her films it’s exactly the same. In certain sequences, Miéville multiplies the shots of a face, feeling perhaps the need to model it, to make it distant, to separate it from the other, the interlocutor. In Lou n'a pas dit non, for example, Lou (Marie Bunel) is filmed in close-ups, alone, when she instructs (the instruction is a Miévillian motif) Pierre (Manuel Blanc), her lover, to forget: “You have to know how to forget memories, to have the patience of waiting for them to come back. They come back and they become gazes, gestures, and they no longer have names.” The form, if we examine it, if we look for it, if we try to describe it, appears as articulated in the way silence pulsates, then inhales. A contractual silence. Uncovering, as if at low tide, islands of exchanged words, of dialogues, of conversations, of exchanges with the art of the great composers of language, music or sculpture. This matter, drawn from silence, produces the nature of the shots and formulates the space. “Silence is a form.” (Claude Royet-Journoud, Une méthode descriptive, 1986) In Miéville, the image is closed/open; shots of Nature, of faces, of traffic, of transport, not connected to obvious sounds. The silence is there for her gaze to resonate. Hers and ours. (The filmmaker’s gaze is our gaze). In addition, the silence is a form altering the painstaking idea of an off-camera by abolishing and ridiculing it. There is a constant presence of actors. There is no empty shot, or only very furtively, that corresponds to what the characters see, or to what they could see, or better, to that which they can’t be confused with, the scenery, the others, the crowd. Their presence in the shot is inseparable from a confrontation with the other, visible or not.

Mon cher sujet (1988), her overwhelming first feature film, begins with a funeral, the sacrament of silence, of “beloved voices that have fallen silent” (Verlaine). That reminds me of a fragment from Là où le temps est un autre by Anna Maria Ortese, who describes the silence that follows hell, in this case her brother’s death: “In my opinion, this silence that follows all deaths, even that of small beloved animals, corresponds to a sort of blackout of the soul,” and a little later in the same paragraph: “Part of the soul is gone forever. And the soul reacts by no longer listening to any noise, any sound, any voice of the surrounding nature and of its own life.” Miéville reinvents our way of listening when in mourning, makes us hear (and understand) the echo of reconstructed things. She imprints a partition, the loud voices and the sounds that overlap, that get carried away and exhaust the silence. From Mon cher sujet onward, what is present in the scene, the light in a shot, the resonance of the voices of Agnès (Anny Romand), the mother on the phone, of Angèle Renoir (Gaële Le Roi), the singing daughter, and of her friend Carlo (Yves Neff), all that resounds seems to come from elsewhere. The soft voice of Odile (Hélène Roussel), Agnès’s mother, doesn’t resound. She’s full of silence, a voice from the scenery. Agnès’s and Angèle’s voices feel as if they’re returning from a journey, the way the obvious returns, from the ether, from a closed world without dreams, without clouds, hidden, forgotten, buried before the film in order to come back to it and leave an imprint. Right after the first note of the film, an organ piece only slightly precedes the first shot at the very end of totally silent opening credits, the funeral pomp (of others) at the church. Miéville films two solemn children, serious “seven-year-old poets” (Rimbaud), receiving condolences from adults at the resounding close of the service. We won’t know anything more, it’s enough, about these children who had such a short time to learn and mourn what they’ve only known for a couple of years with a never-to-return intensity. Before they’re even capable of imagining themselves alone, they are alone. In Nous sommes tous encore ici, Jean-Luc Godard, as an actor on a stage, reads Hannah Arendt: “In solitude we are never alone, by ourselves, we are always two-in-one, and we become one, one complete individual [...] only thanks to others and when we are with them.” The present of these children is already a memory, that which is made simultaneously with the body.

In Miéville, the desire for order is the desire for cinema. At times, it seems like she’s preparing the film, that the recording and the découpage of the space slightly precedes the mise-en-scène of their resonance. In an interview with Olivier Séguret who, at the time, was one of the only ones, together with myself in Cahiers du Cinéma, to write a favourable review of Après la réconciliation (her last film, made in 2000, and why aren’t there more? What happened to Anne-Marie Miéville’s precious Present?), Jean-Luc Godard, who acts in the film and accompanies Miéville for the occasion, says: “Like Carné, Anne-Marie is the only one that could replace ‘editing’ with ‘technical découpage’. In fact, it’s one and the same thing for you: the technical découpage is the editing’s script.”2 A forging of Time presages Anne-Marie Miéville’s films, by separating moments from the outset, by multiplying the starting points of stories. Her cinema shows continuity of thought, without anything in this sequence of statements of her thought bearing any dirty traces, like fingers of newspaper readers, of whatever judgement or opinion. It’s an impressionistic kind of cinema, which transmits the refusal of conventions, the desire to express “the impression felt before the spectacle of nature or of modern life” through the modulation of light, of colour, of movement, and through the time required for a specific silhouette, through the composition of frames entirely organized around spots of light and colour, by the window or lamp, by this character in that scene, at that time.

To introduce, Miéville depicts an echographic prologue in which her voice probes the images with questions (“Why are you laughing?” she asks, and the little girl starts again), editing shots from different sources between those images, from home movies, always with children, to fixed photographic shots of doorsteps, of garden flowers, even showing copies of shots from Nous sommes tous encore ici. A little later in the film, a different beginning: shots (location scouting?) of weeds, of wild flowers growing under people’s footsteps, solitary and forgotten between city pavements. It also happens there, where memory is heterogeneous, neither historical nor collective, but singular and linked to the outside world, where only Miéville is operating, moving forward (we picture her stepping aside) in order to develop her films. About the shots of weeds, Miéville says the following to Séguret: “I wanted to film this population of ingenious little weeds that I had discovered while walking, perhaps at a time when I tended to hang my head. I realized how difficult and threatened the life of these weeds is, being pulled out every day. Metaphorically, I also considered them fixed characters in the middle of people passing.”3 Nous sommes tous ici is introduced by an off-screen dialogue – which blurs our reading of the opening credits, white on black, usually silent – between voices of an invisible woman and man deciding on a film project, of this very film in fact, which was refused funding because: “Poetry is over!” states the man in charge. The film’s images start with an off-screen dialogue between clearly identified voices, those of Jean-Luc Godard and of Her, the director (not Miéville, I think, but Aurore Clément appearing in a crowd of pedestrians being pushed by a silhouette, which could very well be Anne-Marie Miéville, from behind), who says: “They don’t want it.” Godard’s voice responds: “They don’t want it, but we do. There are still twenty francs on the table, so take them and let’s go!” We see an alternating montage embodied by a split between two flows, between two modes of transport, each interpreted by an appropriate rhythm and music. A very resounding kind of classical music is mixed into the crowd of pedestrians and the cars drive around to the rhythm of jazz music. The characters seem to emerge from a chaos of sound. They arise in the shots like potential, but often failed, harmonies. In the foreground, the sound is what identifies the shots and the silent points in the image, within the depth of field. What is formed in silence is a kind of speech, a renewed dialogue between two sonic beings, be they humans or music. The highlight of her film work – comprising of four feature films and a medium-length film, and in addition to the great films co-directed with Jean-Luc Godard, between Ici et ailleurs (1973-‘76) and Détective (1985) – is the overwhelming Soft and Hard (1985). Made by the couple, it depicts Anne-Marie Miéville’s enthusiasm and her concrete work as an editor, researcher and creator. Further, we notice that this achievement is due to a source that is essential for both her and him: the confrontation with the other’s mind. For once, the battle between the sexes is not only embodied sexually, nor by the virtuosity of diction (Hawks), but by intellectual intimacy, extreme attention and the testing of each other’s sensibility. And then there’s the acute melancholia, paired with that which cuts, with blades, les lames (as those of knives) in French, which is another word used to say the waves (les vagues). As in Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, in which most of the words cut, slice, separate, block.

Angèle Renoir, the young protagonist training as a singer, tells Carlo she’s pregnant –two-in-one. Then she sits on the hospital bed after an abortion (inhaling) without even an ounce of pulsation of another inside of her. She’s right in front of us, puts on her headphones, and we, resolutely with her, hear what she’s listening to: Léo Ferré, Les amants tristes. She’s interrupted by the staff of the clinic. This operation, not the abortion which does the exact opposite, but the hope of being two-in-one, which relates one into one, not one plus one, doesn’t have a name. Its practitioner is called Anne-Marie Miéville and Murnau could be the one who invented it. Something internal surfaces through the image (Sunrise), in this case through sound: the partnership Sonimage, which dates Miéville’s presence in Godard’s films. The sound in the image is a sign of recognition of her cinema. One of the most beautiful sequences is the fantastic singing lesson in which Angèle is tested by a teacher. She sings an audition classic, O del mio dolce ardor, a fragment from Gluck’s opera Paride ed Elena, and Miéville multiplies the points of view of this sung allegory. The teacher sings with her in a shot in which they’re both filmed from the side, and they share an immense happiness, a strong emotion. He caresses the air that surrounds her, as if, with hands that don’t touch, but catch and set the pace like a spell, an enactment; or with his feet tapping, he emphasized her singing, punctuated it, encouraged it, loved it. His learned, lively and joyful hands could be the hands of a midwife, of a doctor, of a lover, but here they are the gestures of a spectator that is deeply moved by the irrefutable fact that his body will not touch the other’s body over there, close by, in itself, on the screen.

- 1Marie Anne Guerin uses the French idiomatic use of the word silence in a play on words which expresses that “she” (elle - AMM) not only keeps silence, but keeps “the” (le) silence. Through the use of the personal pronoun and the definite article, Guerin shows that Anne-Marie Miéville’s silence isn’t just an impersonal, vague presence. [Note by the translator]

- 2Olivier Séguret and Philippe Azoury, ““Jean-Luc a insisté pour jouer”. Miéville et Godard racontent leur harmonie sur le tournage”, Libération, 27 décembre 2000.

- 3Olivier Séguret and Philippe Azoury, ““Jean-Luc a insisté pour jouer”. Miéville et Godard racontent leur harmonie sur le tournage”, Libération, 27 décembre 2000.

With thanks to Marie Anne Guerin

Image (1) from Nous sommes tous encore ici (Anne-Marie Miéville, 1997)

Image (2) from Le Livre de Marie (Anne-Marie Miéville, 1985)

Image (3) from Mon cher sujet (Anne-Marie Miéville, 1988)

Image (4) from Après la réconciliation (Anne-Marie Miéville, 2000)