Speaking with Godard

Wilfried Reichart About German-French Film and Television History

From about 1970 onward, Wilfried Reichart shaped the WDR-Filmredaktion in various capacities, leading it from 1980 until 2004. He was involved in the production of numerous film-promoting television formats, which introduced the international cinema to the viewers by means of interviews, reports and reviews. Especially in this capacity, Reichart had several conversations with Jean-Luc Godard and grappled with his work in reviews, articles and essays again and again.1 The following conversation took place in Berlin on two occasions in the autumn of 2017.

Beginnings

Thomas Helbig: Could you tell us how you got interested in the world of French cinema?

Wilfried Reichart: I studied French Literature at the Sorbonne for a couple of semesters, at a time when the Nouvelle Vague was just beginning. I went to the movies more often than to university and went to guest talks at the then IDHEC (Institut des Hautes Études Cinématographiques), where Georges Sadoul and Henri Agel would speak. Of course I was also constantly sitting in the Cinémathèque in the Rue d’Ulm, where I occasionally also saw all of them – and I told myself: I will meet you again [laughs], I promise. And it worked out that way.

Something very similar happened to Godard. First he spent a couple of semesters at university, but went to the movies more often than to class. Later, you wrote film reviews for the Kölner Stadtanzeiger, before you eventually came to the WDR. What made you switch from the newspaper to television? Did you already have the desire to replace the writing desk with the editing suite at that time?

In fact, this is what happened: I was writing for the arts pages of the Kölner Stadtanzeiger, which was my first job. I wrote about film a lot and therefore the WDR-Filmredaktion started noticing me – Reinold E. Thiel, Wilhelm Roth and Georg Alexander. They showed Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915) on television, and I wrote about it. I made fun of the music editing, which I thought was terrible, even though it was done by Griffith himself. Georg Alexander called me and he was furious, thought I was an idiot for criticizing the music editing when they had for once shown such a magnificent film on television. In any case, he was beside himself with rage. On the third WDR channel, there was a programme that had to do with critique. Werner Höfer was the director there. They invited me to this programme. However, they did not allow Alexander to talk to me, because they were afraid we would start a fight. And in this programme, probably with Thiel or Roth, I don’t remember exactly, we talked about Griffith and about the soundtrack and about what a great programme the WDR-Filmredaktion was making. After a while, when Alexander had become the chief of the Filmredaktion, he came to me and asked if I wanted to make a couple of programmes for the WDR. I said yes and edited some programmes.2

What kind of programmes where they? What did you expect from the format change? Which possibilities and promises did television offer you and what was the relation to the movie theatre?

Do you know the series Cinéastes de notre temps?3 The WDR had bought the rights and reworked the programmes in order to broadcast them on German television. I remember, for example, programmes on Luis Buñuel, Jean Renoir and John Ford.4 German versions were made from this material, but I didn’t just translate them. I re-edited them and added a new voice-over. It was new to me. I had never made a film, and I didn’t know what an editing machine was. And then, Alexander asked me if I wanted to join the Filmredaktion. At the time, it was difficult to find a vacancy at the television department – which would then result in a permanent post – so I started at the WDR as a “permanent” freelancer. I received a fixed salary, but I was still a freelancer. Nowadays, I am sure no one would do that anymore: switch from a permanent job at the newspaper to that kind of uncertainty... I then worked as a freelancer for about two years until there was a permanent position and I became television editor at the WDR.

A quite well-known statement by Godard, which he made to you as well, indicates that the almost ten years of working in film critique, for Cahiers du cinéma among others, were to him as if he had already made films. Did you experience something similar?

Yes, it was always emphasized that film critique was a kind of preparation. We should once more look at his language more closely and compare it to that of Truffaut and Rivette. A strange phenomenon somehow. I don’t think there is anyone nowadays who first writes reviews and later wants to seriously get into making films.

Maybe someone who is involved in the magazine Filmkritik? Harun Farocki and Hartmut Bitomsky for example.

Yes, but they haven’t done any real film critique. They wrote about film from a specific perspective without really considering themselves film critics, I believe.

Do you think something has fundamentally changed in present-day film critique?

In the case of current film critique, we could reflect on the fact that you can work in much better conditions. At the time, we always had to write from a vague memory. Today, the film you have seen is lying in front of you on DVD or Blu-Ray, and you can immediately check any aspect or any association you have. But what does it mean for film critique and for your own perception? I grew up with an interest in cinema, but I didn’t actually know much, because there was a lot we couldn’t watch. If you were lucky, you had seen a retrospective. Nonetheless, certain things stuck. Do you know the film Blast of Silence (1961), for example? It’s an American film produced around the same time as À bout de souffle (1959). I had seen the film and I’ve never forgotten it! It’s a gangster movie – a gangster comes to New York to kill someone, undergoes a crisis and ends up dead – that’s the story. It was American Nouvelle Vague – really nice! So when I was at the WDR, I thought: we should show that film. No one here knows it. So I tried to find who had produced the film, but I didn’t find anything. The film had completely disappeared – even the director had disappeared.

Where had you seen the film?

I had seen the film in a theatre at the beginning of the 1960s. Atlas, or some other small German distributor, had shown the film in theatres. That’s where I saw it and never forgot about it. I told everyone I met, in France, in New York, in Los Angeles: “I am looking for Allen Baron. When you find him, let me know!” One day, I get a phone call: “I have found Baron. He’s a television director in Los Angeles; this is his phone number.” I called him, and we talked. He was amazed. That anyone would remember his film, he found unbelievable. We arranged to meet each other the next time I was in Los Angeles. I met him there, and he didn’t stop talking. A tragic example of filmmaking, probably. He starts with an extraordinarily great film, as good as À bout de souffle. Then, it doesn’t really continue. He makes another film, which isn’t that interesting anymore, looks around, looks for producers, doesn’t find any and finally ends up in California, becomes a television director and directs series. Famous series even... And that became the life that he would accept. He never made another film for the movie theatre, but he did countless other things. I told him: “I will make a film about you.” I went all over New York with him, to all the locations from his film. In every location he talked about how they had shot the film, on roof terraces and all sorts of things. Then, a film was produced on all of that.5

What kind of curiosity is it, really, to trace the genesis of a film in that way? What can the additional background information add to the film?

I learned something about a man’s life – that’s it! Also the tragedy. In Baron’s case, for example, there was also the fact that he suddenly thought that the film that I was making was his own film – in a sense, it was, as I didn’t interview him. I accompanied him to several filming locations, together with a camera team. He was a brilliant actor. He was even dressed in the same way as in the film, in which he himself had played the lead role.

Director and actor at the same time?

Yes. He’s a kind of Peter Falk, who was supposed to play the role. He was offered another job at the last minute, however, so Baron decided to play the role himself. That was fun! Falk would have pulled another Falk trick, but Baron was entirely the person he embodied. The first shot, how the train arrives at New York Central Station, how the door opens and how he comes out, suitcase in hand, is a really strong shot. The programme talked about this man and about the film, that it exists and how it was shot.

You once described television as a kind of catalogue, which seems to me a very apt description, a medium for listing, looking up or classifying.6 That supposes, first of all, a rather modest position. On the other hand, we could connect this classification to a remark made by Godard in one of your interviews. According to him, television could also be understood as a laboratory, which allows for an analytical way of examining objects. The complexity of film on the one hand and society, science, aesthetics, culture and technique on the other are brought together in a reduced model: “We see the whole, which is impossible in film,” is what Godard says.

The question then becomes, what is film and what is television? The way you’ve just described it, television is the attempt of trying out several things in a fast and simple way and with different techniques – on the other side we have film. But now such a distinction no longer exists. So I wonder, what is film? Another example: When have I seen the Mona Lisa? When I see the painting in a catalogue, or when I am standing in front of it in the Louvre? When I now transpose this to film and say: When have I seen a film? When I have seen it on television or even on a cell phone? Have I really seen the film in that case? Or is film defined by the projection in a cinema? Many people who write about film use the word “cinema”, which is somehow confusing. Cinema is no longer only the location, but also something else – however it is pure invention. We always talk about cinema instead of, for example, about cinematography. We say: “The cinema of the 1960s” – and by that we mean the films, not the location. How do you see the definitions of these terms?

I think there are different historical perspectives, with constantly shifting notions. For Godard’s time and by analogy with his comparison, we could say that cinema was a place of production, while television was a place of reproduction – much more focused on communication and information than on aesthetics. This is what Godard captures in the model, that cinema is a matter of projection and television a matter of rejection, which seems a very productive opposition. At the same time, he considers television a means of researching and examining when he says: “Television is just a phase of film, which I would call the script writing phase." He comes to a remarkable observation, by the way, which indirectly also touches on your work for the WDR: “What is wrong is that television people never make films and film people never make television. Everybody works for himself, although both should work together.” You and others from the WDR-Filmredaktion at the time undoubtedly took this step.

No, that’s not true in my case. I always knew I wouldn’t make any films in the strict sense of the word – the “films” I have made are essays, programmes, journalistic works, but not films. At the same time, I also knew that many of those who made these kinds of programmes didn’t know they weren’t able to make films. [laughs]

Speaking with Godard

What struck me is that you always met Godard in situations in which his work was either radically transforming or in which this transformation was already clearly imminent. In Cologne in 1971, Godard is almost at the end of the Dziga Vertov Group7 phase. In 1976 you visit him in his newly designed video studio in Grenoble. In 1979 he had already moved to the Swiss town of Rolle, where he has lived ever since. While looking back on his political films, he had in 1976, with the television series Six fois deux, already discovered the video technique, series, and television. In 1978, he has finished this sociological-documentary phase with France tour détour deux enfants and has already developed the first ideas for a historiographical project, which will later lead to Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-98). I would like to ask you some more questions about these pivotal and turning points. But, to begin with, what interested you in the person of Godard?

Honestly, I have always been fascinated by this person. I like the constant rebeginning, the permanent calling into question, in order to then take another step. I find that incredibly exciting about him. This fundamental attitude. The principle of his thinking is always to say no. Not accepting what already is, but putting everything into question when it is perceived. That’s how he makes À bout de souffle. He knows all the rules of cinema and leaves them behind. He’s not looking for connections. He doesn’t do shots and reverse shots... and all that. The principle of his thinking is to say no... That’s what you need to see in his films.

In your interview with him from 1979, there’s an interesting part which has to do with exactly that. There, he speaks about how it came about – out of necessity, rather, as there was too much footage – that he rigorously and with a certain brutality acted against the footage during the editing of À bout de souffle.

Exactly, and that produced a new style!

Twenty years later, without any sign of regret, he concludes: “Today, advertising does exactly the same.” There, the possibility of making other films was gone for him, so there was no reason to continue on the same road. The only tradition Godard feels committed to is the tradition of breaking with tradition – even if it’s his own – again and again.

That’s the difference between him and all the others. Rivette has always made the same films, Truffaut as well, and Rohmer very extremely so. They have all found their style and followed it through until the end of their lives. Godard is the only one who hasn’t done this. That’s something which really fascinated me. And he was really insecure in the beginning and didn’t really know what he had to do. He sees all of his friends who don’t really take him seriously. Chabrol, Rivette and Truffaut – they are already making films and he can’t, until Truffaut offers him this story and he turns it into “the film” À bout de souffle. That was not really to be expected. In the biography by Antoine de Baecque, we learn a lot about that time.8

Maybe it’s not a coincidence at all that in the interview from 1979, of all films, Godard returns to À bout de souffle. The style, which was shaped by this film twenty years earlier, was replaced by the aesthetics that go hand in hand with the video technique. Although the kind of films he made had already extremely changed long before, the switch to video is a fundamental transformation. It leads to a new style, which fully corresponds to the intentions of reflecting his means of working more strongly. That’s probably what he means when he contemplates, during the conversation, the handling of the pencil, with which something is put on paper. Undoubtedly, the pencil represents the camera and the idea that it doesn’t only matter what we film, but also how we film it. His film Caméra-œil (1967), in which he is almost constantly in the frame when handling the camera and reflects on what is out of the frame, most certainly pushes this aspect to the extreme.

The most interesting part of everything he does is the reflection – the political films he makes aren’t films that change the political situation. They are, however, films that reflect on the medium. And the most interesting political film from the Dziga Vertov Group phase is, I believe, Ici et ailleurs (1974), in which he reflects on all of this: “What have I made, and how do the images work? Why have I chosen this shot?” That is to say, he doesn’t talk about the political content anymore, but about the aesthetic impact. That’s what always interested him the most.

Originally, the project carried the title Jusqu’à la victoire (from 1970 on) and had to document the political conflict in Palestine. When the victory didn't occur, the whole project was jeopardized. Together with Anne-Marie Miéville, Godard then re-edited the footage in 1974 with the title Ici et ailleurs. Tellingly, it was precisely at that point that Godard used video. The available 16mm footage was transferred to video and subjected to an analysis during the video editing. The film itself is a kind of pivot or hinge, towards a different film form.

Cologne in 1971 - Film Politics, Hindsight and Reflection

Once more back to the beginning. Together with Georg Alexander, you conducted your first interview with Godard in Cologne in 1971. How did that come about?

It came about because we broadcasted his films – which was crucial for him. Indeed, we were the only ones who showed his political films on television. We showed films like Pravda and Lotte in Italia (both from 1969),9 much to the chagrin of our managers and directors. Of course, they thought what we were doing was horrible. That was my access to Godard: “You show my films, and we talk” – that was the deal. And then I came to Cologne, and we sat at a table and talked. I still remember it. He came together with Jean-Pierre Rassam, a French producer. I still remember how I drove out of Cologne with him afterwards, in order to show them the direction of the motorway. [laughs]10

As you already mentioned, at the time of the interview, Godard started making “political” films. The programme you produced together with Alexander shows, apart from the interview, countless film fragments and thematizes the break with Godard’s earlier film production, which manifested itself in the naming of the “Dziga Vertov Group”. How did you feel about this transformation in the context of your own experience of seeing films? Was there any disappointment about Godard turning his back on cinema?

No, not at all; it was a time of politicization. And, like Godard, I also politicized. I wasn’t the only to take to the streets in May 1968; I was part of the aesthetic revolution. [laughs] And we had the possibility to realize this on television. We were the only ones to show these films. The third WDR channel had six versions – in Hamburg, Frankfurt, Munich, Cologne, Stuttgart and Saarbrücken – and they met once or twice a year, and everyone could show the films the others had shown. That is to say, they all could have shown these Godard films without having to pay – but none of them did!

You already mentioned the dissatisfaction of those in charge. Still, it was possible to show the films on the WDR?

Also at the WDR people were shaking their heads in disbelief. Werner Höfer said: “How can you show such films?” But Höfer had a big heart. He told himself: “My editors know what they’re doing. Even when I don’t like it.” Maybe it also had to do with his unfortunate role in Nazi times, which caught up with him later on. Because later they proved he had made anti-Semitic statements as a young journalist. He made the big mistake of wanting to sweep it under the rug instead of talking about it. He should have said: “I was indeed blinded, an idiot and a fool, but I have learned something” – that would have saved him. But he didn’t say that, so when he became more known afterwards, it was a scandal. In a private context, this background had turned him into a very open-minded, generous and liberal human being. He didn’t want to censor anything. When you went to see him, he would always mockingly ask you: “What do you have for me now?” But anything was possible. [laughs] That was the political attitude that led to showing the films, to wanting to see the films. We never thought: “Damn, why doesn’t Godard make any decent films anymore?”

Grenoble in 1976 - Sonimage and Video (1973-1979)

And then, in 1976, you visited Godard in Grenoble, where he had founded the video company Sonimage together with Anne-Marie Miéville.

That was a beautiful kind of encounter, because it wasn’t primarily an interview. It was more of a work conversation: I came to his studio in Grenoble, with an endless amount of monitors just standing there, videotapes everywhere and all that. He showed me what he had made and then we went to eat something, sat together and came back to the studio. We knew each other. Of course, he had always given the impression that interviews with him were entirely superfluous. Why interviews? It is important to make and show films instead... No, he was really very nice and perhaps he liked me as well. It really was an intense working atmosphere, which was only interrupted when my team arrived. Then he had to sit down, the technical side was installed and it suddenly became television again.

Did you also record the interview on video at that time?

Let me think... I believe we shot on 16mm in Grenoble.

That must have been a bizarre situation for Godard.

Absolutely! There was a full WDR team present, including a cameraman, a sound engineer and a production assistant, and they installed their own lighting in his video studio. That was pretty absurd. I do remember Godard was very patient. He watched it happen – but I have no idea what he thought about it. [laughs] We did, indeed, shoot on film. We talked for a long time and part of the footage was made into a film for the WDR.11 But I'm afraid the rest of the footage is gone. We did not yet have a pronounced sense of preservation, which is of course quite dumb.

In the recently published Fragmenten einer Autobiographie [Fragments of an Autobiography] - the first volume of Harun Farocki’s writings – there is a wonderful passage on this. He says he found the editing remains of your Godard interview in the wastebasket when he was a freelancer at the WDR. He took the material home – a form of “productive theft” is how he calls it.12 It was transcribed and printed in Filmkritik. It’s a story that could have been taken from a Godard film.

That’s true! That’s how it went. I then edited the interview and wrote an introduction. Unbelievable [laughs], how he was sneaking around the rooms, looking for something to take.

In the introduction you mention that Godard showed you something from Six fois deux.13 Was he interested in your opinion?

He showed me some episodes and we spoke about those. For me, it was just information. It was a new format, remembering it wasn’t cinema. I didn’t want to form an opinion on it. It was about seeing what he did and how he did it – which is what I asked him. Some things I found beautiful, some amusing and some not very interesting. What he produced in Grenoble was very hard to broadcast, because they were series. We would have needed extra time slots, but a feature film editorial department doesn’t really have any time slots for series. So we made choices and broadcasted a couple of episodes.

So you were faced with the difficulty of translation. That’s a problem which is not easy to solve in Godard’s case. Already then, and next to the different audio tracks, Godard used numerous text insertions, which necessarily had to collide with the subtitles that were added later.

Exactly, so it was either subtitles or a voice-over. We frequently bickered over that. The purists were all for subtitles – because otherwise the original voice was lost. What they forgot was that subtitles destroy the image [laughs] and that the subtitles change the way of seeing. You constantly jump back and forth. Let’s take a film like His Girl Friday (1940) by Howard Hawks, in which someone is speaking from the first until the last second. You wouldn’t even be able to watch this film because of the sheer amount of subtitles.

Only read...

Exactly! A solution could be – it’s a theory of my own – that we could understand any film when we get some information beforehand. When you know what it’s about more or less, we could even understand a Japanese film, like one of Ozu’s. We would see the images and we would see them so intensely that we could indeed understand. We could conclude from the characters’ movements the internal state they’re in. That would be a highly interesting form of watching films.

Because the images and the movement represent a form of speech that is seldom adequately translated into words.

Right. But of course it was unthinkable that we would show a ninety-minute Japanese film on television without subtitles.

That a famous director like Godard turned to television and preferred a technique like video was a big influence at the time. Among other things, he did a talk about his switch to video for the association of Swiss film and AV producers that same year.14

Yes, he said that we had to move towards television, that we could find a larger audience there, that we would be able to communicate there. We can no longer do that in the cinema. Other films dominate cinema. The films he was making at the time had no place in the cinema. On television everything seemed possible. For example, he would have liked to make a film on FC Bayern München in order to show the dramaturgy of a football player. But no one was interested.

Rolle in 1979 – Making History

In 1979 you visited Godard one more time. That was the time when he and Miéville were working on the series France tour détour deux enfants15 and the idea of working with the history of cinema was already clearly emerging.

Yes, it started with the question, “What is he doing now?” I visited him in Rolle on Lake Geneva, where he still lives these days. Something funny happened there. I recorded the conversation, went back to the hotel and found out that there was nothing on the audiotape. The worst thing that can happen. [laughs] I then immediately ran back to his office and told him: “Something horrible has happened. There is nothing on this tape recorder.” Then he said: “Then we just do it again.” In the end he let me use his tape recorder.

Did you speak about the work he was doing at the time?

Yes, he even got a little pedagogical. He was making France tour détour deux enfants, but something wasn’t right. The network that had originally ordered the series didn’t really want it anymore. Godard found himself a new form there, in the sense that he suddenly started getting interested more in people. People who aren’t actors. He talked with them. They had to tell him what they did and why they did it.

In the context of your interview in 1976, Godard handed you a document titled Histoire(s) du Cinéma et de la Télévision. It consists of twenty photocopies that show idiosyncratic image and text edits produced by Godard, scissors and glue. As far as I can tell, that is the earliest attestation of a project that would eventually produce the four-and-a-half-hour-long video work Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-98). The pages were printed, together with the interview, in the magazine Filmkritik and developed a certain influence afterwards. Siegfried Zielinski, for example, later published one of the collages in his book Audiovisionen (1989).16

Yes, I remember. Zielinski once told me about it...

Friedrich Kittler also included one of the collages in his book Film, Grammophon, Typewriter (1986). [image (3)]17 The publication in Filmkritik infected all of them. Apparently the mere sketch of a film project struck a nerve. You return to this project in the conversations of 1976 and 1979. The development of Histoire(s) was a project with many different stages. It started with this collage and took a more concrete form in the lectures Godard gave in Montreal in 1977-78. Recorded and transcribed, these first reached the form of a book18 – not without the loss of friction – before the temporary versions of the first episodes were broadcasted on television from 1988 on.

Exactly. He started with the lectures in Canada. The principle was: I compare one of my films with other films and that way I can talk about my films by means of other films. That idea was continued and soon extended to the cinema of the entire world – that was the beginning. And the book – I also really like the first book, because it is full of errors and typos. Frieda Grafe and Enno Patalas then published the German edition. They domesticated it, as it were. That is to say, they turned it into a correct version.19

With regard to the Montreal lectures, you mentioned that Godard confronts his films with other films. That reminds me of the fact – which seems a fundamental step in his oeuvre – that he almost completely resorts to already-existing film material. A form of (re-)production that, in this case, owes a substantial amount to the video technique.

Histoire(s) du cinéma

I believe that with video he was able to think faster. That was the reason. What always bothered him in conventional filmmaking was the fact that it took too long. In the beginning it is terrible: you always have to wait until something has been copied and can be watched – which is totally opposed to his way of working. And what he liked, he showed in Histoire(s) du cinéma: he is holed up, gets everything he needs and is able to work with it in such a way that he is at the same time producing something. But where does he suddenly get the idea of making Histoire(s) du cinéma? What does he really want? He doesn’t want to create film history....

It depends. He says, I am making a film history – but not by means of writing, but of video. A kind of film-written film history.

But we need to understand that he isn’t pursuing a film-historical discourse. He is interested in other things. Once again, it is a reflection on images. But it’s not a film history in the way of Sadoul.

Nevertheless, the historical is what interests him foremost. He just doesn’t use the documents like a positivist who wants to shine a light on a specific historical moment. It rather concerns a perspective on history, which also aims at a poetic moment. A film philosophy with a historical background. A narrative that doesn’t only go back to the beginnings of cinema, but reaches back all the way to Dante, Virgil and Homer. That’s why Godard draws from scientists and historians like André Malraux and Élie Faure, whose language reflects a certain closeness to poetry and literature.

And he always shows himself in how he works! Others making films only seldom show themselves. Film historians who would make a film similar to Godard’s would show movie clips and interviews with authors and directors. They would reflect on tones, music and editing, and they would demonstrate all that. They could say, “That is how Bresson frames...” and then show everything. And what does Godard do? He shows himself and what he does – and that is a completely different attitude.

Still, it is worth noting that he doesn’t present himself as a filmmaker, but as an author at a desk. [image (1)] He could have also shown himself in the editing studio. But he doesn’t do that. Instead, he opts for a form of staging that should look a certain way. The image of being holed up is striking and reminds us of a variety of iconographies. A bit like the famous Hieronymus cave. The scholar who withdraws from external temptations like a hermit. Why this kind of theatricality, while Histoire(s) doesn’t contain any other staging, except for the many image manipulations? Can you explain this?

Keep on experimenting! In the sense of doing something in order to see how it works. And then you can change it; that’s his principle. At times, it reminds me of the famous Kleist text on the gradual production of thought while speaking – that’s how he makes films. He starts thinking, develops something and sees if it works. I remember, for example, the image in which Lilian Gish is lying on an ice floe. There’s a location, he describes a scene with an ice floe on a river with Lilian Gish... and then he suddenly starts reflecting. What does he demonstrate there?

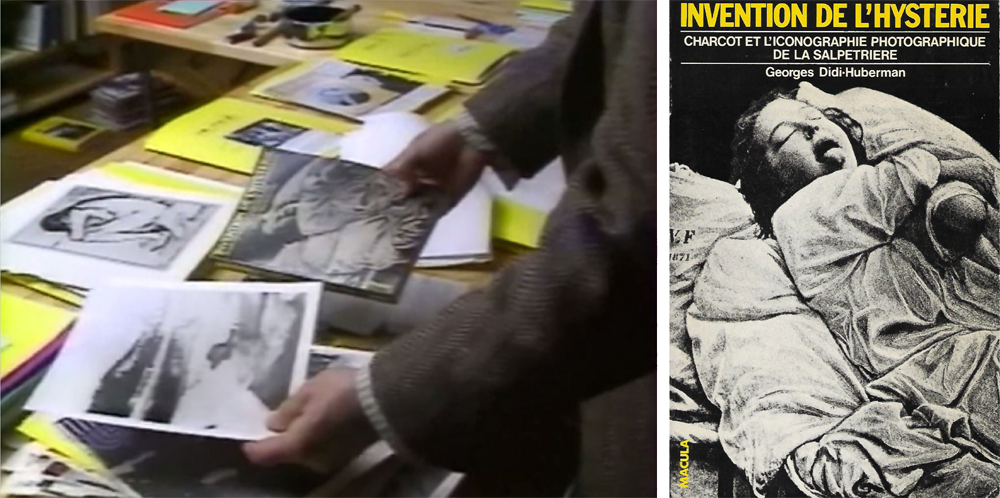

There is a particularly revealing document on that, which demonstrates this thought in particular. In 1987, he was interviewed by the French film magazine Cinéma, cinémas.20 In the interview, he gives a perfect example of his way of working with video. He is sitting at his desk in Rolle and picks up this image in particular, among others. Next to it, he is holding the title page of the book Invention de l'hystérie [Invention of Hysteria] on which we can see a photograph of a woman during a hysterical attack. [image (4)] Georges Didi-Huberman, the author of the book, referred to this comparison on several occasions.21

Godard has adopted the theme in his Histoire(s): the photograph of an unconscious Gish from Griffith’s film Way Down East (1920) – a photo with Griffith on set – and then a picture which shows Jean-Martin Charcot, neurologist and teacher of Freud, during a demonstration of a hysterical attack by a female volunteer – like a clip from the image on the book cover. [image (2)]22

In this form of “cross-fading” he ostensibly combines psychoanalysis and film history. But in addition, he also seems to want to ask the question if the strangely overstated, exalted gesture of Gish’s portrayal does not also have a contemporary real core. Why does the image have such a memorable, iconic effect? Surely because of the gesture’s strangeness, which finds a distant echo in the hysteria documented in Charcot. We could perhaps argue that Godard tries to apply the methods of psychoanalysis to film history and to what is unconsciously enclosed in it. The way you, on your part, have described the surplus that is produced when we connect films to the circumstances of their production.

Yes, film is something very concrete and constructed, in contrast to music and visual art. The director has to constantly deal with so many people... that’s the definition of film.23 I think, for example, that film history focuses on directors too heavily and never speaks about producers, only whether or not they were sympathetic. Which is wrong! After all, the film producer is the first spectator. He has his own interests, the way a spectator also has his own interests, namely: “I pay money and I want to see something that meets my expectations.” Surely that is the exact definition of a producer. [laughs] The producer looks at the example with that kind of awareness. And his reaction can be interesting for the director as well, which is exactly why this interaction can be tense.

It is exactly this wider perspective that Godard implements in Histoire(s), when, besides the director, he also illuminates the complexities of the producer. You can notice, for example, in the way Irving Thalberg is thematized, whose conflict with Erich von Stroheim is brought in by Godard.

Quoting and (Re-)Producing

In your biographical essay Au contraire, which is very much worth reading, you point out Godard’s penchant for “cleptomania”. Although he came from money, he initially suffered from a constant lack of money, which grew into downright property crime. Even the cash register at the Cahiers du cinéma wasn’t safe for him. I wonder if it is the same unscrupulousness that makes him appropriate the many quotes constantly populating his films. In a certain way, he turned his cleptomania into an artistic method.

Although we need to ask where this randomness leads. We certainly need to deal with this in a critical way. Hanns Zischler told me that. I believe it happened during the production of Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro (1991). Godard was at Zischler’s house, which has a huge library, and apparently blindly took books from the library and used quotes from them for his films. Of course, we can say it’s amusing, but is it okay? What does he make out of that? But in the end he makes something out of anything.

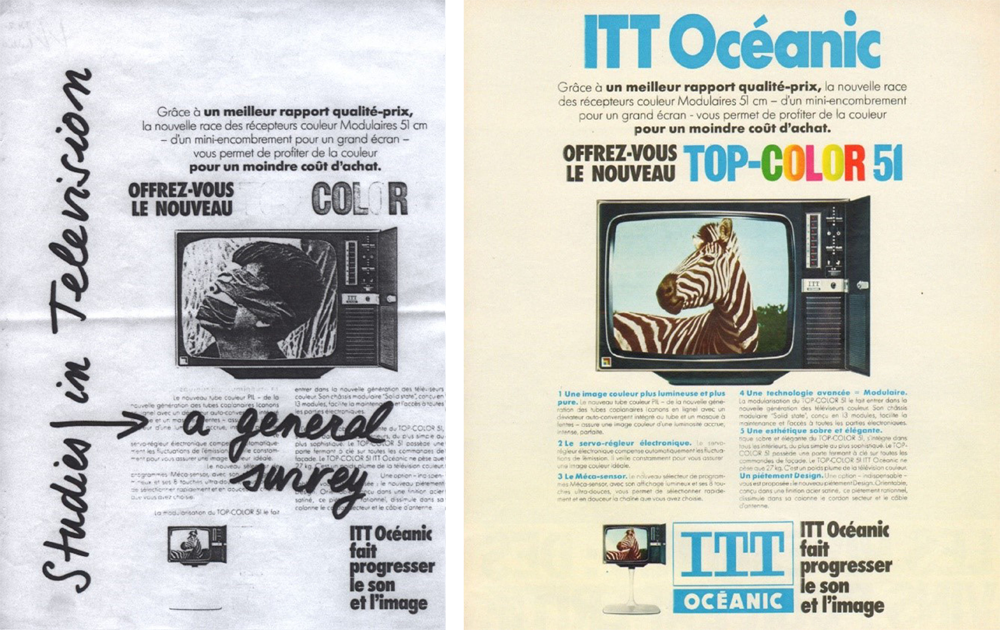

In this collage, for example, in which he swaps the image of a zebra – a stock photograph which was curiously found suitable for a colour television advertisement – for an image from the Vietnam War. [image (3)] A banal everyday image replaced by an image of reality. Both seem to not really fit together, are opposed, but are part of the same era. We could also think of Martha Rosler’s series of collages Bringing the War Home (1967-72/2004-08). Just like in Godard’s case, the war penetrates the living rooms at home.

Yes, taking everything without asking a lot of question. That’s what he has in common with Brecht – just taking and using.

It reminds me of another comment by Zischler, made in the context of a screening of Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro.24 Godard didn’t just take some quotes from the books; he also cut out whole images.

Imagine him sitting there with a pair of scissors, playing and editing – you don’t just quickly do something like that! Always with the question, what can I make out of it, what is hidden in there? Surely, it’s an incredible talent, one which is hard to explain. Where does it come from? Or is it just there?

It’s an artistic capability that extends well beyond the filmic frame of reference. He plays with these image documents as if he were a collage artist. And part of these cut edges end up in the film edit. In Histoire(s), all the material is defined by this kind of postproduction. Often, he uses the video aesthetic, with its cross-fades and distortions, in a painterly way. In doing so, he is both artist and critic, constantly comparing and thinking in constellations. It never remains only one image: “I have one image... but what other images are there? Is it a suitable image?”

Also in order to structure the seen and to find a clear form. He makes sense out of what is hard to define or name. On their own, all pages make sense.

And they perfectly mirror the technical development of a certain historical period, including all of its illusions and utopias.

And where does he come from, really? There is the bourgeois environment of his parents. He wanders about, precariously. Finishes school only at the last second, because it all doesn’t really interest him, hangs around, watches and travels North and South America at a very youg age, together with his dad, who is a doctor. Then he works as a labourer at a dam project. That’s what his first film Opération béton (1955) is about. That is to say, he doesn’t really know what he wants yet. He doesn’t have any focus. And that corresponds to his way of thinking. Not a focused but an experimental way of thinking. Just seeing where he will end up...

Despite the fact that his language gives us a different impression. As if he knows very well what is to be done.

Yes, he’s constantly explaining something. Tells us how things work. That is so strange! And not even in an entertaining way, but in an educational, pedagogical way.

Cinema with(out) End

Early on, Godard said: “Cinema will die young.” This thought pleased him somehow, that cinema would have to die young, like Rimbaud, [laughs] and would then be resurrected in a different form. But analogously, he has said: “What is 100 years of cinema if we compare it to 2,000 or 3,000 years of music and visual art?” The cinema that dies young. A thought which isn’t right, of course. Because it becomes something else. But cinema as an institution is already dead in a way, or has become something else. When you look at DVDs, Blu-Rays, that’s not cinema anymore; but everything is available. In this respect, something fundamental has changed. Everything is there. Only cinema is no longer there.

But you’re forgetting that the article in the Süddeutsche Zeitung that you published on the occasion of your visit to Godard and of his video works of that time, carries the title The Cinema of the Future!

Yes, but today cinema has become something else. I recently noted down a quote by Godard on this subject. In it, he says: “The digital image is not an image. It is the description of an image. Cinema means giving – but prior to that we need to receive. Today, nothing is received anymore, only captured. The surface of the image is the same at each point. We could also call it the democracy of the pixel.” The rigorousness of his wording, as if he knows exactly: “Today, nothing is received anymore, only captured.”25 [laughs] That is so strange! There is always indignation on the state and stupidity of the world that is resonating.

Yes, it’s a deep-seated rhetoric. Often, he contradicts himself. His thinking and speaking is driven by a certain many-voicedness. It’s something he clearly indicates in one interview: “Two years ago, you said this, and now you say that. Isn’t that a contradiction, Mr Godard?” at which point he replies with a diabolical smile: “Yes, of course!” Despite the scepticism that resonates in your quote, he was entirely comfortable handling digital techniques. Whether it be a simple handycam or 3D cinema, like in the recent Adieu au langage (2014). He reproached the video image for its flatness. Still, it was precisely in this technique that he found the condition of critique and analysis. To stay within the image of his formula: he contrasts the technologically founded shallowness with the importance of a more substantial way of working with images and tones. This notion of work, which he deploys again and again, is fundamental to his approach. Perhaps he holds on to it, in preparation of his films, in order to produce these somewhat outmoded-looking collages with scissors and glue.

Possibly, it also has to do with a different understanding of his role as author. Similarly to what you called it in your quote and to how Kaja Silverman phrased it, he sees himself as a receiver.26 An author who doesn’t create originals, but edits and combines. It’s also a means of getting away from a situation in which everything that is said in the films leads back to him as originator. That’s the many-voicedness once again, which also finds its material condition in the quotes. He “democratizes” his way of seeing and makes himself permeable – as a first spectator – for the frictions that arise from things that come together.

You need a very open mind for this, and you need to be prepared to be influenced by what’s around you. Maybe that’s what happened, already from his first films onward. In the choice of shooting locations, for example, which often arose by chance.

Every equation contains at least one variable. Hanns Zischler talks about this in relation to the shoot of Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro. The wider framework was the intention, by analogy with Rossellini’s film Germania anno zero (1948), to paint the portrait of the former DDR, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. So, a new “zero hour”. Zischler chose the locations for the film in advance, completely autonomously. There is a scene in a big brown coal mine close to Leipzig. In the middle of this no man’s land, Godard decides to make the Don Quixote character suddenly appear on a country road. Here, the monstrous machine, which, as Zischler rightly pointed out, “swallows” a landscape; there, a broken Trabant, as a relic of a time gone by; and in between, there’s Eddie Constantine, who wants to find out “the way to the West” from the just as disoriented Don Quixote. [image (5)] In this very peculiar mix, of a concrete historical with an abstract poetical aspect, the scene suddenly receives its very own obviousness, which captures a certain historical mood beyond the visible.

Exactly... this thinking in the moment. No philosopher is searching for a final truth.

He doesn’t present us with final answers, but he points backwards. The spectators can only take the material to try and weave their own Ariadne thread, which leads them through the labyrinth of images, tones and texts.

Prospects

From today’s point of view, it seems unfortunate that the many programmes produced by the WDR-Filmredaktion are so difficult to access. That is something of a paradox. Originally, the programmes were there in order to make the films known with the broader public; today, however, a considerable effort is necessary to even find them. Do we need a catalogue for the “catalogue”?

Sometimes such programmes are included on DVDs as bonus material. With Molto Menz of absolut MEDIEN and a French publisher, I have just re-released Out 1 (1971/1990) by Rivette. The first programme I made on Rivette is on there, which is at the same time the first film I ever made, I believe. It was called Les mystères de Paris. And then together with Robert Fischer, a film historian from Munich, I made a ninety-minute film on Rivette and the authors, which is on the French DVD edition.

Did you ever meet Godard again?

Do you know Harald Bergmann? He’s a German filmmaker who has made a Hölderlin trilogy. His last film is a film on Nabokov. For me he’s one of the most interesting filmmakers working with literature in Germany, but he is considered marginal or an outsider. He wanted Godard to play the old Nabokov.27 Then I said: “Let’s just ask him! But we don’t just call or mail him – he won’t answer. We go and take the risk!” So we drove to Rolle, went to his office, rang the door, and no one was there. Well, bad luck. So I wrote him a message on a piece of paper – with a fountain pen – because I know that’s what he prefers to read. And I wrote: “Dear Jean-Luc, we were just in the neighbourhood. It would have been nice to see each other, but unfortunately it didn’t work out. This is my phone number, and so on.” Then we went to a bar in Rolle, and suddenly my phone starts ringing and it is Godard! He still has this slightly trembling voice. And he said: “Come over.” So we went and talked. Bergmann presented his project to him and asked him if he didn’t feel like playing the role. Godard said no, that he wasn’t an actor, etc. But nevertheless, we were with him for about one hour and talked. That’s how it went and it was very easy!

In 2006, Godard had his exhibition Voyage(s) en utopie at the Centre Pompidou. You wrote about it in the magazine Film-Dienst.

Exactly. And of course everything went wrong again. It is difficult with him, because he’s radical and quickly becomes offensive. The question is how to deal with him. And officials often don’t find the right tone. You should also have this attitude of saying, when you’ve decided to do something with him, he can do anything. And the problem with officials is that they say: “I want to be there. I want to check it”, and that they then say: “No, that and that’s impossible. Couldn’t you do it that way?” ... And then everything goes wrong. The exhibition was almost cancelled.

As far as I understand it, the exhibition was ultimately more of a proposal – the sketch of a possible exhibition or, taking up the title, the utopia of an exhibition.28 And that, again, is very convincing in relation to his approach and thinking: as long as at least one idea is visible, no matter how rough and unpolished, the thing is valid, worth it.

After all, the unfinished also has its qualities... That’s his principle. Also in Histoire(s), Godard is more poetical than concrete.

Do you also keep in touch with other people from the cinema or television realm?

Sometimes you just accidentally meet. For example, I have recently seen Straub. There is a Straub/Huillet exhibition at the Akademie der Künste [Berlin], where he visited one of the events. He was just sitting around, a little morose, and we talked briefly. Did you know that he lives in Rolle, just like Godard? Imagine how they encounter each other on the main street. [laughs] I recently also met Anna Karina. We arranged to meet, sat in a bar and spoke. We could almost only talk about Godard, which might have disappointed her a little. She also looked a little disappointed in life. Those aren’t interviews, just simple get-togethers. Inspired by the idea that I have gotten older, while the others got even older than that. [laughs] Their work has accompanied me and they’re still there – that’s how you sometimes meet. I also visited Agnès Varda that way. We sit there – I’ve known the people from her office for a pretty long time – and she sits there with her cat, and we talk about a thing or two. She also told me that Godard – “the rat!” – turned his back on her. In her last film, called Visages, villages (2017), she drove through France’s countryside with a young photographer and they took pictures of people and glued huge blow-ups on walls of houses and open spaces. For example, a house with a facade that’s showing a postman. And then she talked to the people. A visually absolutely exciting film. She also wanted to visit Godard, but he bailed on her and she was furious. In the beginning, they were together very often. Godard, Jacques Demy and Varda often played cards together.

In Varda’s film Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962), Godard and Anna Karina do a very touching performance, recreating a silent film romance on the occasion of their marriage. And Varda and Godard had exhibitions in Paris at the same time in 2006. Godard at the Centre Pompidou and Varda at the Fondation Cartier.

That’s how I constantly meet someone. For example, Rudolf Thomé, who’s no longer making films. Thomé has made many films that have also all acquired their place in film history. Thus I ask myself: what does that mean? Is that simply something personal, or is that interesting as well? What does that mean then? People meet each other and everyone has a story.

Are you planning on writing something about that?

One could write an essay about film directors that have stopped directing films [laughs]. Perhaps, when the decisive impetus would appear. You don’t want to constantly walk around thinking you have to do something. We like to drink as well. [laughs] Just recently, we organized a dinner at our house with Norbert Grob and Wieland Schulz-Keil as our guests. Schulz-Keil produced the last two films by John Huston. We sit together and talk, film history is present, and a lot of wine is consumed. [laughs]

- 1See bibliography.

- 2About the WDR-Filmredaktion, see also both conversations from 2008 by Michael Baute and Stefan Pethke “Nicht nur Filme zeigen – ein Gespräch mit Wilfried Reichart [...]”; as well as “Was wir machen wollte, haben wir gemacht - ein Gespräch mit Georg Alexander [...],” in Kunst der Vermittlung. Aus den Archiven des Filmvermittelnden Films.

- 3The French television series of most monographic productions started in 1964.

- 4For a compilation of film-promoting programmes at the WDR, see “Filmografie, Kino im Fernsehen: WDR,” as in note 1.

- 5This is the film Allen lebt hier nicht mehr [Allen doesn’t live here anymore], 1990, 40 minutes.

- 6See the conversation with Baute/Pethke (note 1).

- 7The members of the Dziga Vertov Group were, besides Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin, Jean-Henri Roger, Paul Burron and Gérard Martin. Before the group disbanded in 1971, it released six films, most of which were produced for international television networks. For this, see Volker Pantenburg, “Politik der Konfusion. Jean-Luc Godard und die Filme der Dziga Vertov-Gruppe,” in Ränder des Kinos, Godard – Wiseman – Benning – Costa (Cologne: August, 2010), 13–29.

- 8Antoine de Baecque, Godard, Biographie (Paris: Grasset, 2010).

- 9Both films were broadcasted on the WDR in 1971 and again in 1974. In the case of Lotte in Italia, which was rejected by the Italian television, it was a television première. Ici et ailleurs was shown on the WDR in 1977.

- 10Politik – 24 x in der Sekunde. Das neue Kino des Jean-Luc Godard, 1971, directed and written by Georg Alexander, production: Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) Cologne, 52 min. 30 sec.

- 11Kinoʹ 77, 1977, directed and written by Michael Klier and Wilfried Reichart, production: Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) Cologne, 41 min. 40 sec. Besides Godard, the programme also focuses on Claude Sautet.

- 12Marius Babias and Antje Ehmann, red., Harun Farocki, Zehn, zwanzig, dreißig, vierzig. Fragment einer Autobiografie (Cologne: Walther König, 2017), 160.

- 13Six fois deux, together with Anne-Marie Miéville, 1976, 610 min., video, colour, 12 episodes.

- 14Jean-Luc Godard, “Die Video-Technik im Dienste der Film-Produktion und der Kommunikation,” Filmkritik 22, nr. 7 (1978): 358–369.

- 15France tour détour deux enfants, together with Anne-Marie Miéville, 1979, 12 episodes, each 25 min., video, colour.

- 16Siegfried Zielinski, Audiovisionen, Kino und Fernsehen als Zwischenspiele in der Geschichte (Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1989), 17. A short version of the interview was included by Zielinski in an anthology he published: Video. Apparat/Medium, Kunst, Kultur. Ein internationaler Reader (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1992), 197–209.

- 17Friedrich Kittler, Grammophon, Film, Typewriter (Berlin: Brinkmann & Bose, 1986), 191.

- 18Jean-Luc Godard, Introduction à une véritable histoire du cinéma (Paris: Albatros, 1980).

- 19 Jean-Luc Godard, Einführung in eine wahre Geschichte des Kinos (München: Hanser, 1981). For the programme Kinoʹ 81, Reichart produced a short contribution with a review of the book. Further contributions in the programme: Wieland Schulz-Keil [Peter Lilienthal], Hartmut Bitomsky [Godard’s Film], Thierry Filliard [in memoriam Abel Gance], 1981, production: Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) Cologne, 43 min. 05 sec.

- 20Cinéma cinémas, Claude Ventura, Michel Boujut, broadcast on 20 December 1987, A2/ France 2.

- 21See, most recently, George Didi-Huberman, Passés cités par JLG, Lʹoeil de l’histoire, 5 (Paris:Les Éditions de Minuit, 2015), 39–43.

- 22It concerns a painting from 1887 by André Brouillet, Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière. The title of the book is: Georges Didi-Huberman, Invention de l’hystérie, Charcot et l’iconographie photographique de la salpêtrière (Paris: Macula, 1982).

- 23Reichart not only interviewed Godard in 1979, but also the cameraman Raoul Coutard and the editor Agnès Guillemot. Both were involved in several productions by Godard.

- 24IKKM-lecture from 18 January 2017.

- 25 Katja Nicodemus and Jean-Luc Godard, “Kino heißt streiten [ein Gespräch mit Jean-Luc Godard anlässlich der Verleihung des Europäischen Filmpreises],” Die Zeit nr. 49, 30 November 2007.

- 26Kaja Silverman, “The Author as Receiver,” October 96 (2001): 17–34.

- 27This idea later generated Bergmann’s film Der Schmetterlingsjäger, 37 Karteikarten zu Nabokov, 2015, 135 min. See also: Bert Rebhandl, “Ein Interview mit Harald Bergmann,” Der Tip, 16 July 2014.

- 28See also: Thomas Helbig, [Review on] “Anne Marquez, Godard, le dos au musée. Histoire d’une exposition”, regards croisés nr. 5, 2016.

Originally published as ‘Mit Godard sprechen. Wilfried Reichart über deutsch-französische Film- und Fernsehgeschichte(n)’ on new filmkritik, 6 March 2018.

With thanks to Thomas Helbig and Wilfried Reichart

Images (1) and (2) from Histoire(s) du cinéma (Jean-Luc Godard, 1988-1998)

Images (3) and (4) Godard's collage and the original

Image (5) from Allemagne 90 neuf zéro (Jean-Luc Godard, 1991)