Interview with Florent Marcie on A.I. at War

The Revolution of our Times

Thibault Elie: Your previous films take place in theaters of war – Chechnya, Afghanistan, Libya – where you were shooting alone, without a crew. But here you are accompanied in the conflicts zones. How did this project come about?

Florent Marcie: This idea came up a few years ago while editing my film Tomorrow Tripoli about the Libyan revolution. I was living in Libya and while reading many publications about the progress of algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI), I thought that personal computers had reached a sufficient degree of power that I, without being an expert working for a laboratory, could start using these “intelligent” technologies. I was absolutely convinced that we were now all on the threshold of this technological revolution.

In Libya, I was also struck by a coincidence: in mid-February 2011, at the exact moment of the outbreak of the Libyan revolution, Watson, the artificial intelligence developed by IBM, beat the American champions of the TV game show Jeopardy, a general knowledge game. After having filmed various “traditional” conflicts and revolutions over the past quarter century – deeply human battles that belonged in a way to the Old World –, I wanted to make another film about this other revolution. It seemed to me that what was unfolding under the name of “artificial intelligence” had a revolutionary scope that was deeper, more total and more universal than the other upheavals I had witnessed. This was not easy to admit: the main revolution of my time was in fact that of algorithms. Instead of going to interview scientists, I imagined an original way of filming: to bring a humanoid artificial intelligence with me to the battlefields. This approach corresponded to my trajectory and my way of working. I wanted to see what this AI could provoke in the population, what it was able of, and how I myself would be transformed, or not, in contact with it.

Searching for the Robot

Where did you find Sota, the robot that accompanies you on the battlefield?

For my project, I was looking for a small “intelligent” humanoid robot that would be like an assistant-companion. It had to be easily transportable, to be able to talk to me, to respond to me, to learn certain things and to film. A new film is always an opportunity to explore and experiment. What interested me was to telescope the world of AI and the tragic, but so human, world of war and struggle. That was the general idea. My intuition pushed me to go in this direction.

It was a crazy gamble because I wasn’t sure of anything. I didn’t even know if the device I was looking for existed. Would I be able to find a small humanoid robot that could talk, film and learn? Such a robot was not available for purchase. Scientists told me: “Wait! Don’t believe what the media says! No robot is capable of doing what you want to do!”

But I finally found the device I was looking for. One day, in Paris, I was wandering through the aisles of a large technology trade show when I saw a little robot sitting on the corner of a table, under a sign that said: Imagineering Institute, Malaysia. On the stand, while questioning the botmaster, named Sasa Arsovski, I learn that he is Serbian and that he grew up in Vukovar. Vukovar is a city that was razed during the war in the Balkans. I had photographed this war in 1992. So the robot had an indirect relationship with the war and my own history. I set up my camera and talked to Sota – the name of the robot – to test it. I ask “him” some simple questions: “How are you? What is your name? Do you want to come with me to Syria?” That’s when he says, “I love your sense of humor”. I was stunned. I said to the Serbian botmaster: “Don’t laugh, I absolutely need this robot for my film. I have to take it with me to Mosul. This is the device I was looking for.

The project started at that moment. I had found the robot, all I had to do was to get permission from the research lab in Malaysia. I jumped on a plane and went to explain my project to the director of the Imagineering Institute. In the lab, researchers came from all over the world: Nigeria, Yemen, Iran, Sudan, Chad, Pakistan... The director was himself a chinese-greek mix. After 15 minutes, he told me: “I am interested in your film, we will lend you the device”. I put Sota in a small suitcase and left for Mosul.

Sota, the A.I. Who Saw

How does your Sota robot work?

With Sota, everything goes through the cloud, i.e. the Internet. When I talk to him, my voice is sent to the laboratory’s servers in Malaysia. There, algorithms, which have been trained in conversations, generate answers. These answers are sent back to Sota who expresses them aloud thanks to a voice synthesis system. In practice, I ask Sota a question, I wait a few moments and he gives me his answer. In order for me to work with the robot, I need an internet connection that is stable and relatively fast. Which is not usually the case in a war zone...

For several years, the general public has been familiar with this technology through chatbots and voice assistants from Google, Apple or Amazon.

Yes absolutely, my robot looks like these technologies. But there are several essential differences. First, Sota has a humanoid shape and he is cute. The mere fact that he looks like a small child creates empathy and attachment for our primate brain. Emotional attachment is a major issue for artificial intelligence to gain acceptance. Sota’s naive appearance also creates an interesting contrast with the tragedy and violence, a mixture of candor and irony.

Another important difference is that Sota has a personality. He is not just an assistant who will give answers to your agenda or your latest text messages. He has an age, tastes, but also a sense of humor. That’s what particularly appealed to me about the Malaysian laboratory’s chatbot project. Because he was developed with a personality, Sota is a little character, a companion. In addition to being able to answer a lot of questions and search for information on the Internet, Sota can film, photograph, analyze and describe what he sees. He has many functionalities and he can acquire new ones.

Sota, an Experimental Machine

What does the robot bring in addition to your “classic” camera?

The image seen through the eye of a robot does not have the same value nor the same meaning as the same image filmed by a human camera. Thanks to the presence that we assume behind Sota’s point of view, we have access to his subjectivity. A subjectivity that induces a change of perspective in the look and ethics. Filming a tragic situation in the company of a robot that also films and gives its opinion allows us to take off from current events and geopolitical analysis, to free ourselves from certain codes, to innocently transgress. The perspective becomes more historical, more universal, but also more subversive. The innocent subjectivity of the robot broadens the perspective to the human species with a twist of tragico-burlesque.

Did the robot evolve during the shooting?

Following the first shooting in Mosul, I returned to Malaysia with the desire to improve the device. When I realized that the researchers in the lab wouldn’t take the time to make all the modifications I wanted, I learned to code. Without being an expert, I managed to make some improvements and created new functions, but the deep part of the algorithms, especially the conversational capability, remained inaccessible to me. Sota can learn if it is programmed in a way that it can learn. In general, there are keywords that trigger learning. For example, if I tell him, “Learn: the old city of Mosul is completely destroyed,” he will memorize what I say.

Mosul, a Landscape of Ashes

How was the beginning of the shooting in Iraq in the city of Mosul?

When I found the robot, the battle of Mosul was coming to an end. I wanted my film to start in the smoking ruins of this devastated city, which had served as the Iraqi capital of the Islamic State. Daech was a mixture of archaism and advanced technology. In a way, I wanted the robot to take over from Islamic fanaticism, in the sense that artificial intelligence is also a form of transcendence and religion, even a deity. A trend that will only increase in the years to come.

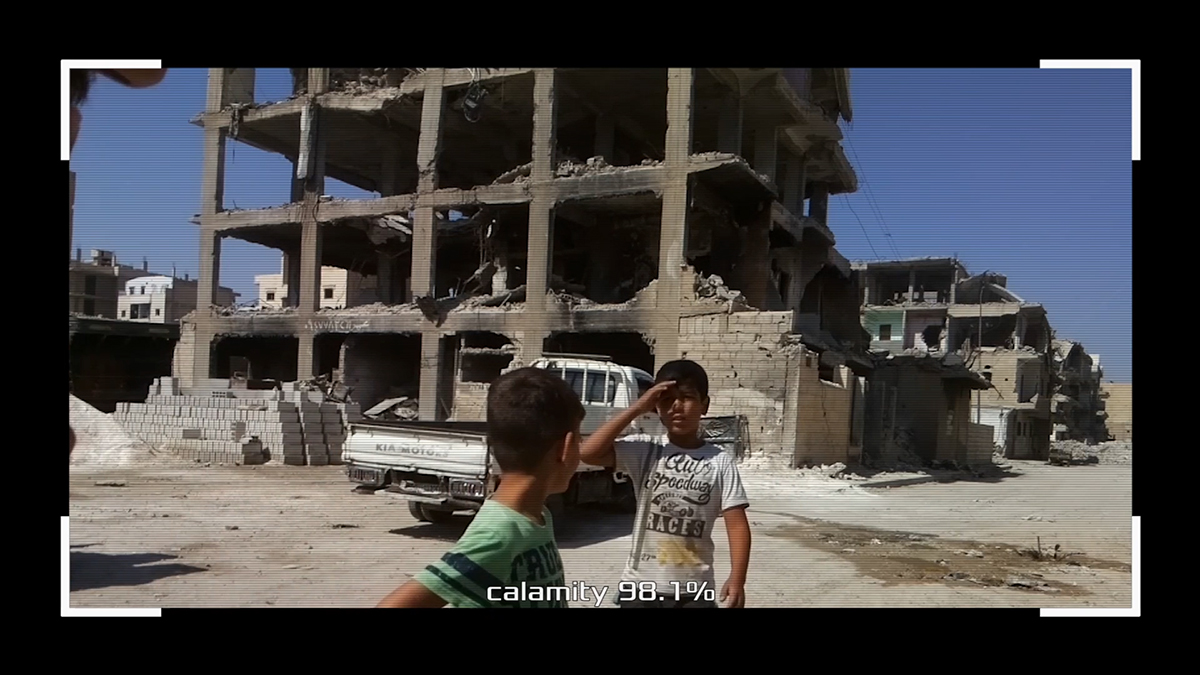

So the film begins in Iraq, in Mosul, at the precise moment of the fall of the Islamic State. When I arrive, there are still some Daech fighters in the ruins of the city, there are still bodies in the streets. But this is no longer the intensive bombing phase. A.I at War is not a war film as I have made them in the past. I’m not looking to film the battle so much as the symbol of destruction and devastation. For me, the apocalyptic atmosphere is a metaphor for our humanity today.

We find ourselves, as a biological and cultural species, in a form of devastation. We don’t really know where we are going and we are threatened from all sides. Artificial intelligence is like a spirit that hovers over our heads and our lives, like an artificial consciousness in the cloud that envelops the earth. Hence the use of drone images. The aerial image evokes the artificial consciousness that overhangs us and observes us.

Mosul is a devastated landscape where no one understands anything anymore. There are ruins, smoke, destroyed mosques. In the middle of the chaos, there are also euphoric fighters. As they won the victory, they sing, they dance. I try to capture this fleeting and absurd moment with my little robot.

Was it easy to work with Sota?

No. From the beginning of the shooting, I encountered great technical difficulties. When I arrived in Mosul, nothing worked. The robot could not even connect to the Internet. In order not to miss the fall of Daech, I had left the Malaysian laboratory in a hurry, without knowing how to use the device. Neither the robot nor its algorithms were made for the use I wanted to make of it. Sota had no battery, only a power outlet. So I had to cobble together external batteries and find all sorts of technical solutions during the shooting.

Alongside the Yellow Vests

While you were editing your rushes from Iraq and Syria in Paris, the Yellow Vests revolt broke out in France. Why did you go to film these demonstrations, which were not in a theater of war?

When I started filming in Mosul, I had no idea – no idea at all – where I was going to shoot and where the film was going to take me. It was a total exploration for me. And of course, I had no idea about the future Yellow Vests movement either. But this was not a problem – on the contrary – since the principle of the film was precisely to throw myself into the unknown with my little companion. If we know how to use chance, we make it our own. So I navigated by sight, driven by the sole intuition that Sota had to be confronted with humanity in its struggles and its excesses.

After the Arc de Triomphe on the Champs-Élysées was vandalised, I thought Sota had to experience this version of unexpected violence at the Yellow Vest Movement too. I had gone to film the war in distant lands, and here it was knocking on my door with a different face. A less warlike, less violent, less tragic face, but a symbolically very strong face: Paris, the City of Light, in the grip of riots. When I arrived at the demonstrations, I immediately understood that I was witnessing something unprecedented. Never before in France had I felt such a special atmosphere among the colorful crowd of protesters. This atmosphere reminded me of other situations that I had filmed elsewhere. I could feel it in the air, in the energy that circulated, in the look in people’s eyes, in the great solidarity, in the serious happiness of being there, which could be read on people’s faces.

Almost the beginning of a revolution...?

Yes, we felt a typically insurrectionary atmosphere. The demonstrators were determined. They were sure of their right. There was no union, it wasn’t just slogans. People from all over France had come to Paris, people who, for many, did not usually demonstrate. To see them gathered in this way on the Champs-Élysées was particularly powerful.

How did the filming go with the Yellow Vests?

The shooting conditions were both very different and complementary to those I had experienced in Mosul or Raqqa. So I modified my way of filming accordingly. Often, the situation was very chaotic: people were running left and right, the police were firing tear gas and shooting at the demonstrators with rubber bullets.

Sota was not always activated because it took a few minutes to turn it on. It’s a fragile device and I had to constantly evaluate whether it was appropriate to take it completely out of the bag. Plus, I didn’t know what the reaction of the police or the protesters would be when they saw this robot wearing a little yellow vest. With a robot in my hand, I didn’t really look like a journalist or a filmmaker.

But filming in Paris had a huge advantage: the internet connection was much more stable, which allowed me to talk with Sota while walking. So I was able to film moving scenes with the robot, impossible to shoot in Mosul or Raqqa.

Surveillance and Revolution

What do you think is the relationship between the Yellow Vests and artificial intelligence?

The relationship lies in the role of algorithms. If the question of algorithms was not explicitly present in the debates and claims of the Yellow Vests, it was in fact at the heart of their movement: it was even the alpha and omega.

The alpha, because this movement was initially organized thanks to social networks and smartphones, i.e., tools that rely on algorithmic underlayers that make extensive use of forms of artificial intelligence. It is thanks to these tools that the movement has been possible and that it has strengthened, to the point of endangering the power in place. In fact, these tools carry within them, intrinsically, “revolutionary” potentialities against any type of power. In every community or country in the world, we can find injustices, good or bad reasons to protest and, eventually, to fight against the authorities. The difference is that in the previous world we did not necessarily have the means to make it known and to organize. In our world, this becomes possible.

But algorithms are also the omega of the Yellow Vests movement and of all protest movements that use social networks, because, on the other hand, these same technologies also allow the powers to observe from the inside, to get information from the inside, to monitor from the inside. It is not only the Yellow Vests who use technologies. The political and economic powers, the police, the army use them intensively for surveillance purposes. When I film the demonstrations, these thoughts accompany me. I have the conviction that the Yellow Vests movement is located at the hinge of the old world and the new world. That they still have one foot in the traditional and “archaic” world – that of the struggle in the street, of physical confrontations, of the wounded – and that they also have one foot – like all of us – in the world of AI that is coming: surveillance cameras, facial recognition, data collection. We are all threatened by this dizzying evolution of the world. I am filming the moment of blossoming.

Who is your film for?

For everyone, because everyone is concerned, but more particularly for the youth, because the future is in their hands. This youth – unfortunately or fortunately – has no more time to wait. It is not a carefree youth like mine. It is a youth that must imperatively take hold of this question, to make counter-powers appear.

Seize the tools! Learn! Don’t just be consumers of social media. Learn this knowledge and learn all you can! It’s a whole world that needs to be reinvented.

![]()

With thanks to Florent Marcie