« Il y a ici un autre principe de base, principe que très peu, sauf les grands comme Chaplin, connaissent : c’est l'économie. Faire une grande chose avec rien, c’est ça le truc. Alors qu’il est de coutume de faire tout le contraire : on montre absolument tout, quoi que ce soit, tout est bon. Résultat : il n’y a pas d’émotion, parce qu’il n’y a pas d’économie. Économie de tout. Des gestes, par exemple. De cette façon, les gestes, quand ils sont faits, disent beaucoup. »

Robert Bresson1

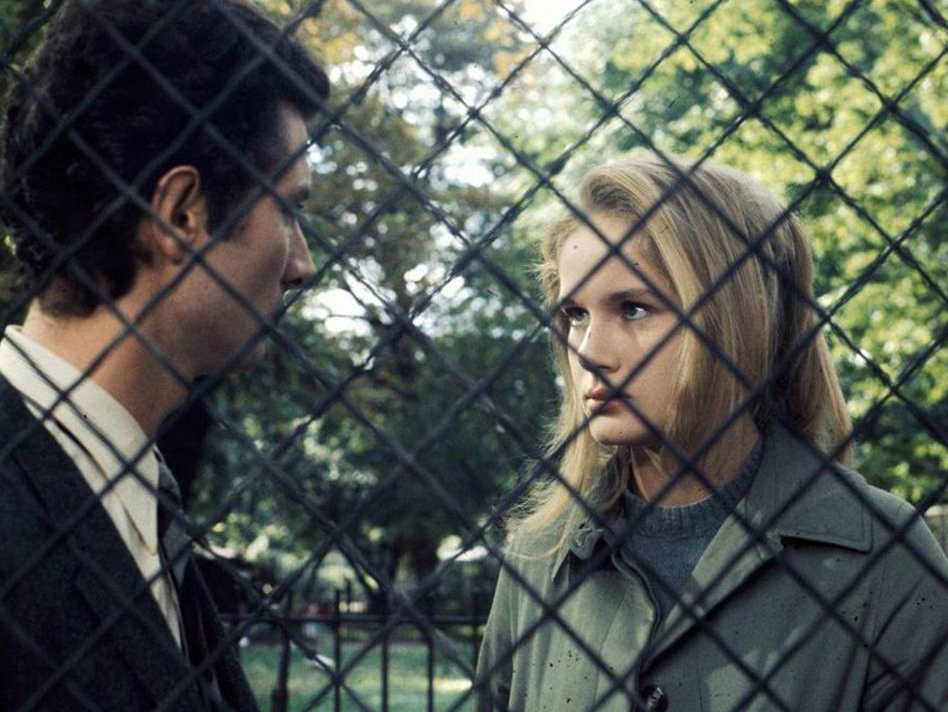

“On one level, the film is a geometric ballet of doors opening and closing, people exiting and entering, husband or wife turning down the bed covers, of objects or people moving into and out of range of the stationary camera, a young wife’s dazzlingly white fresh face against the sharp, crotchety profile of her black-haired husband, TV sets turned on and off, bathtubs filled and emptied. Despite the stylized repetitions of gesture, the rigidly held camera angle at stomach height, the uninflected voices speaking desperate, passionate lines, Une Femme Douce is an eerie crystalline work, a serious affirmation within a story of suicide.”

Manny Farber2

“[...] a revolt against the moral and psychic deformation of man which is caused by the evolution of capitalism. Dostoevsky’s characters go to the end of the socially necessary self-distortion unafraid, and their self dissolution, their self execution, is the most violent protest that could have been made against the organization of life in that time.”

Georg Lukács3

UNE FEMME DOUCE de Robert BRESSON - OFFICIAL TRAILER - 1969 from FURY on Vimeo.

- 1Robert Bresson, Bresson par Bresson: Entretiens (1943-1983) rassemblés par Mylène Bresson. (Paris: Flammarion, 2013), 342.

- 2Manny Farber, Negative Space: Manny Farber on the Movies. (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2009), 243.

- 3Georg Lukács, “Dostoevsky,” in Dostoevsky: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. René Wellek (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1962), 155.