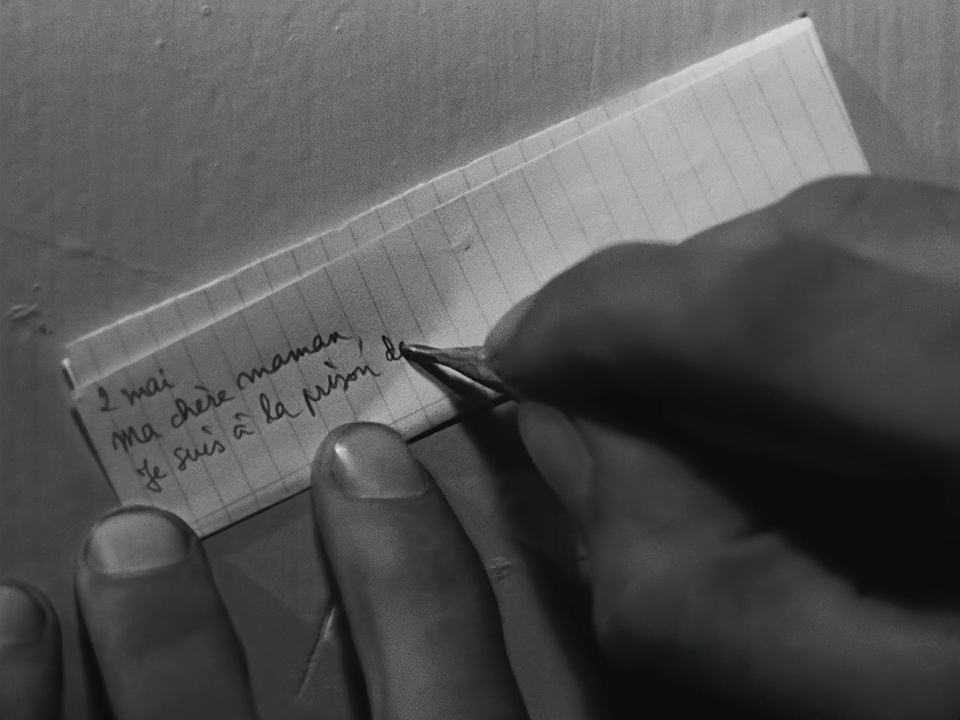

In 1943, Lieutenant Fontaine is arrested by the Gestapo for involvement with the French Resistance and incarcerated at Montluc prison in Lyons. Immediately, Fontaine becomes obsessed with the idea of escape. He has nothing to lose. It is only a matter of time before he will be executed by the Nazis. With a spoon, sharpened into an improvised chisel, Fontaine painstakingly dismantles the door to his top floor cell. He then makes a rope from blankets and the wire mesh of his bed. Just as he is about to make his bid for freedom, another prisoner is placed in his cell, a young Frenchman who deserted after joining the German army. Fontaine now faces a terrible dilemma. He must decide whether to take his young cellmate into his confidence or kill him...

“Cinematography worth admiring—as a new means of expression—has yet to find its poets. Which isn’t surprising in this age of disorder, anarchy, and insensitivity to form. Still, one day we will have to learn to be as expressive with the camera as with the paintbrush or the pen. A film ought to be the work of an individual and invite the audience into the world of that individual—I mean into a world that belongs to that individual alone. I have an elevated view of cinematography. It’s impossible for me to imagine that it will remain forever a means of reproduction (filmed theater) as opposed to a means of expression.”

Robert Bresson1

Cahiers du Cinéma: The mysticism that many of us see in your film: Did you put it there, did it introduce itself without your control, or is it not there in your opinion?

Robert Bresson: I don’t know what you mean by mysticism. What you’re labeling mysticism must come from what I feel inside a prison—that is, as the subtitle of the film suggests (“The wind blows where it wants to”), these extraordinary currents, the presence of something, or Someone, call it what you will, which makes it seem as if there’s a hand directing everything. Prisoners are very sensitive to this peculiar atmosphere, which is not, by the way, a dramatic atmosphere at all: it exists on a much higher plane. There’s no apparent drama in a prison: you hear people being shot, but you don’t react visibly to it. All the drama is interior. Of course, from a material point of view I was attempting to portray this peculiar atmosphere by way of the contact between prisoners: Three words are spoken, and a life is suddenly changed. That’s how it is in prison.

Why is it that for each of the characters we have some idea about where they come from, about their relationship to the outside world, except for the central character, who seems to have no ties?

He has no ties because he has us. In fact, what gives us the sense of being with him is the fact that fundamentally, we don’t know any more about him than he knows about himself.

Cahiers du Cinéma in conversation with Robert Bresson2

- 1Unifrance Film, “A New Means of Expression. An Interview with Robert Bresson,” in Bresson on Bresson. Interviews 1943-1983, edited by Mylène Bresson (New York: New York Review Books, 2016). Originally published in Unifrance Film, 45, December 1957.

- 2Rodolphe-Maurice Arlaud, André Bazin, Louis Marcorelles, Denis Marion, Georges Sadoul, Jean-Louis Tallenay, and François Truffaut, The Wind Blows Where It Wants To,” in Bresson on Bresson. Interviews 1943-1983, edited by Mylène Bresson (New York: New York Review Books, 2016). Originalky published in Cahiers du Cinéma, October 1957.