Aaron Gerow: Among the members of the Ao no Kai, there were many directors who left Iwanami to go independent. You yourself, after making such classic PR films as An Engineer’s Assistant (Aru kikan joshi, 1963) and Document: On the Road (Document rojo, 1964), went on to independently film Chua Swee Lin, Exchange Student (Ryugakusei Chua Sui Rin, 1965). Was there a kind of reaction against PR films entering the era of independent production? Did you yourself feel you could finally produce films as a form of political action?

Noriaki Tsuchimoto: I already mentioned that from the end of the war until I got into films, I lived about 10 years doing things that were not related to film. I had nothing to do with university film study groups, or script research groups, or cinema clubs. But as a spectator I saw enough independent and politically oriented films to make one’s head spin. At one period after the war, I gorged myself on the sort of films that had a clear ideology, and a film grammar that expressed that explicitly, the type that said, “Let’s band together and do it!” I gradually became less responsive to films reducible to such messages, but as for politics itself, I’ve always kept a political way of thinking. But I think that’s different from film expression and enters the realm of sensitivity.

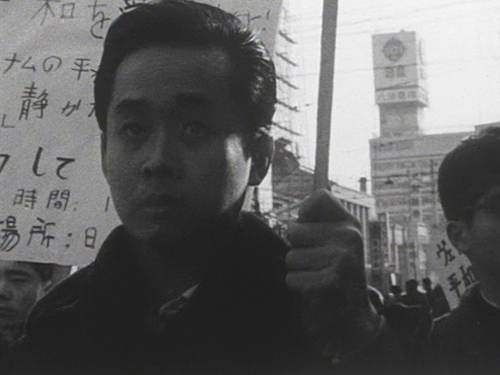

In the case of the film Chua Swee Lin, Exchange Student, the exchange student was just a regular Asian student in the title who wanted independence from the former English colony of Malaya. What drove him out of the university was the same old contempt for Asia held by the Japanese, and you cannot speak about that without bringing politics up. However, what was filmed that really impressed me was when Chua spoke. He had a charisma in expressing himself that seemed to envelop the camera.

I think too much sometimes, so for example, filming the meeting at Chiba University, I just assumed all on my own what they wanted to protest and expected that result to come out. When it didn’t come out the way I expected, I’d think, “This hunch was wrong again,” and pull entirely back and wait, shooting the area or everyone’s backs and continuing my relations with them. I have a saying for my staff which goes, “It’s interesting when predictions are being overturned.” No matter when or what you say, since it’s probably related to what you are wanting to say, I make that unfinished thought or whisper, the change of a small expression very important.

This is true of all my films, but when it becomes a film, the people filmed sometimes say, “Did I say this?” Something is expressed that doesn’t come out in their daily life. In the everyday there is something you could call the non-everyday, something that’s not a lie, not a fake. Film depends on the relationship between the camera staff and the object.”

Aaron Gerow in conversation with Noriaki Tsuchimoto1

“Tsuchimoto’s film became emblematic for the new polititcal documentary gaining footing in Japan. This approach achieved national prominence with Ogawa Shinsuke’s Forest of Pressure (Assatsu no mori /The Opressed Students, 1967). Ogawa had gathered a newsreel-like group of students from various universities for his previous film, Sienen no umi (Sea of Youth, 1966), which was on the problems of distance learning. They called their group the Independent Screening Organisation (Jishu Joei Soshiki no Kai), or Jieiso for short, and it quickly reached national proportions with offices staffed by young activists all over Japan. They found the subject of their next film in the noisy protests of students at a regional university. This was just as the student movement gathered steam in anticipation of the 1970 renewal of the U.S. security treaty, and radical students began barricading themselves in the school grounds. Forest of Pressure electrified the country by showing the passion and seriousness of these students, which was particularly inspiring because it was such a minor school as opposed to one of the elite national universities.”

Abé Mark Nornes2

- 1Aaron Gerow, “Interview with Noriaki Tsuchimoto,” www.eigageijutsu.blogspot.com, April 2011.

- 2Abé Mark Nornes, “Japan,” in: Ian Aitken, Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film (London: Routledge, 2006).