His home is war. Her home is Portugal. Yet the young, newly married wife of Lord von Ketten is determined to turn her husband’s family abode, an inhospitable castle on a cliff in northern Italy, into a real home. When he sets off to battle with his men and tries to send her back to her parents, she decides to stay., To her relatives the house resembles a mausoleum that laments her loneliness. During the long eleven years of her husband’s absence, she reads, sings, plays music, dances, swims and rides in the forest. She also rears a young wolf to which she is closer than to her two sons – or at least that’s what’s suggested by this adaptation of Robert Musil’s novella The Portuguese Woman, which is set in the Middle Ages and features magnificent costumes and opulent images captured by the elegant, gliding camerawork.

“The career of one of Portugal’s best filmmakers has been something of a secret until now – her latest fiction, The Portuguese Woman, is only her 9th film since her 1990 debut O Som da Terra a Tremer. (...) Based on Die Portugiesin, Robert Musil’s 1924 novella set in the Middle Ages, the film was adapted for the screen by the legendary Portuguese novelist Agustina Bessa-Luís, a close collaborator of Manoel de Oliveira and someone whose writing inspired many of the late master’s finest works, like Francisca (1981) and Abraham’s Valley (1993). Bessa-Luís and Azevedo Gomes had already worked together in the 2005 short A Conquista de Faro, produced by another late Portuguese master, Paulo Rocha.

These are only two of the many ‘correspondences’ you can make between Azevedo Gomes and key names in Portuguese art cinema. Another stems from her ‘day job’ as programmer and art director for the Portuguese Cinemathèque, where she was a close accomplice of João Bénard da Costa, the critic and programmer that ran the institution from 1991 to 2008 and influenced generations of Portuguese cinephiles. In 2007, Azevedo Gomes shot A 15ª Pedra, the record of a two-hour encounter between Bénard da Costa and Oliveira, and a film she described, smiling, as a ‘personal confessional’: ‘I wanted to catch those two beings that were so important for my life together, on film, as I saw them in real life.’ Bénard da Costa – under his acting nom de plume Duarte d’Almeida – also acted in films by both directors; it’s no surprise that Oliveira often props up when discussing Azevedo Gomes’ output.

The Portuguese Woman’s theatrical, distanced staging is a good example of her penchant for narrative experimentation. [...] Instead of an on-screen narrator, we have Ingrid Caven, one of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s (and modern art cinema’s) muses, playing a sort of ‘Greek chorus’ that appears out of nowhere at regular intervals, as a ghostly, out-of-time presence that punctuates and silently comments on the work. ‘I was trying to explain to Ingrid something that was somewhat unexplainable: hers wasn’t exactly a role, it was more of a presence. And in the conversation something came up that helped us both: Paul Klee’s drawing Angelus Novus, the one that Walter Benjamin wrote an essay on. You know, the small drawing of the cutest angel with wings, being blown away by the wind, who, upon seeing all the world in ruins, all the rubbish that mankind shows us every day, wants to restart everything, rebuild everything from the ruins... That’s when everything started to make sense, and she had something to go on, something she could draw from.’”

Jorge Mourinha1

“The drab tones of the mist-shrouded landscape at the foot of the mountain imbue Musil’s metaphor for mankind’s dissociation from true values with an extra touch of mystique. In stark contrast with them are the colours of burnt amber, yellow ochre and Prussian blue inside the castle, all adding to the feel of early Flemish painting. Behind the film’s magical cinematography is veteran DoP Acácio de Almeida [his astounding filmography includes Trás-os-Montes, Jaime and Ana by António Reis & Margarida Cordeiro, Pedro Costa's O Sangue, Raul Ruiz’s La ville des pirates, Paulo Rocha’s A Ilha dos Amores, Jacques Rozier's Maine-Océan and João César Monteiro’s Silvestre].”

Marina Richter2

”Cine de la palabra justa, pero también del gesto preciso y de la concentración postural, el reto para los actores de La portuguesa pasa por transmitir sin hacer en exceso, irradiando una intensidad controlada. La cámara no se mueve por capricho, para decorar la acción o entretener al espectador, sino porque hay un motivo para ello. A veces, se trata de acompañar a los personajes o de desplazar el foco de la escena; otras veces, los movimientos de cámara abren o cierran el plano para revelar o aislar a distintos personajes. La directora tiene preferencia por la filmación a distancia y en profundidad, con encuadres amplios que permiten una cuidadosa organización de las figuras en el espacio y otorgan una presencia destacada al decorado. La portuguesa da gran valor al modo en que la luz se posa sobre rostros y objetos, a la textura y color de diferentes materiales y materias: pieles y cabellos; roca y musgo; vestidos, tejidos y tapices. [...] Este film tiene los azules más hermosos.”

Cristina Álvarez López3

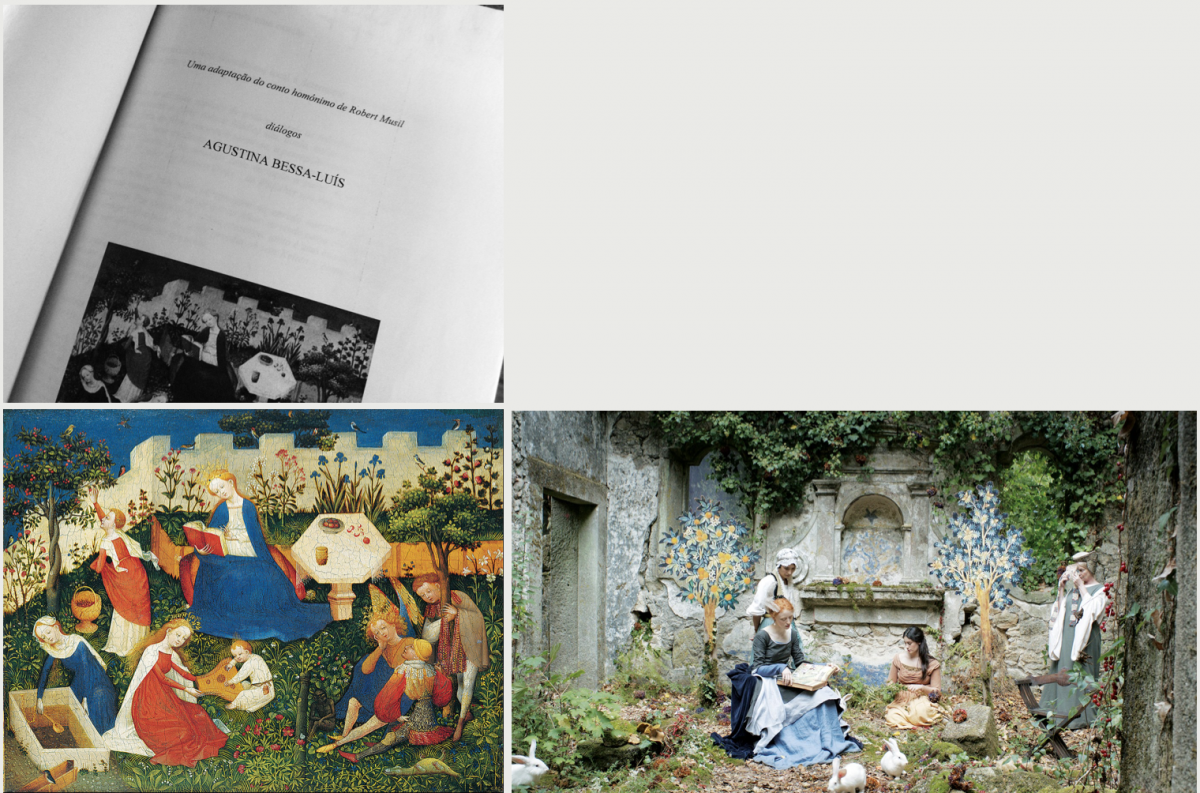

Upper Rhenish Master, Paradiesgärtlein (Little Garden of Paradise), c. 1410, Städel Museum, Frankfurt.

Upper Rhenish Master, Paradiesgärtlein (Little Garden of Paradise), c. 1410, Städel Museum, Frankfurt.

- 1Jorge Mourinha, “Rita Azevedo Gomes: The Correspondences of Beauty,” MUBI Notebook, August 5, 2019.

- 2Marina Richter, “The Portuguese Woman,” Cineuropa, November 16, 2018.

- 3Cristina Álvarez López, “La portuguesa: Un sueño del sueño de …,” Transit: cine y otros desvíos, April 26, 2019.