The face-mask has become unnervingly intertwined with our everyday routines and our social interactions, concealing nearly half of our features, impeding us from smiling to one another, blindfolding our expressions. Consequently, we have to teach our eyes to smile a little more. The expressive power of the face is at the heart of cinema, most apparent in the close-up. “The close-up is the soul of the cinema”, Jean Epstein once wrote. His description points to the sudden apparition of an enormous head on screen, creating a face-to-face encounter with the spectator and carrying a hypnotising intensity. Epstein wrote:

“Shadows shift, tremble, hesitate. Something is being decided. A breeze of emotion underlines the mouth with clouds. The orography of the face vacillates. Seismic shocks begin. Capillary wrinkles try to split the fault. A wave carries them away. Crescendo. A muscle bridles. The lip is laced with tics like a theatre curtain. Everything is movement, imbalance, crisis. Crack. The mouth gives way, like a ripe fruit splitting open. As if slit by a scalpel, a keyboard-like smile cuts laterally into the corner of the lips.”

Once the visage is masked, however, there’s not much left to smile about. This week’s selection consists of films that relish the cinematic features of masks and evoke horror by what is hidden. Each film centres around a face that’s hidden due to some form of gruesome disfigurement. At the same time, each film scrutinises the act of watching the unknown. And as the smile disappears from view, all the while the eyes take centre stage.

Les yeux sans visage (Georges Franju, 1960)

In George Franju’s horror classic Les yeux sans visage, a girl has, as the title suggests, only her eyes left intact after a terrible car accident. Her father and mother lure pretty blue-eyed girls with marble features to their secluded castle in the Parisian outskirts, desperately attempting to find their daughter a new face. Both of them will ultimately prove to go to great lengths to restore their daughter’s beauty. Les yeux sans visage is as lyrical in form as it is sinister. The film inspired countless other face-stealing plots, constituting a great part of the career of exploitation filmmaker Jesús Franco for example, or providing inspiration for the featureless mask in John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) and many other films of the so-called slasher genre. And who remembers Billy Idol’s dreamy hit single Eyes Without a Face from 1983? The film can be watched on LaCinetek, Arte Boutique, myCanal, La Toile and UniversCiné.

Tanin no kao [The Face of Another] (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1966)

What remains only a distant and terrible dream in Les yeux sans visage becomes the starting premise of The Face of Another: namely a successful face transplant. A man named Mr. Okuyama initially suffers the same fate as Christiane, the daughter in Les yeux sans visage, and hides in a mask after being terribly disfigured in an industrial accident. Alienated and frustrated, he decides to accept the offer to transpose a stranger’s visage to his own damaged countenance. What develops is a haunting and formally disjunctive film of existential angst that questions the notions of identity and individuality, mirroring the Japanese identity crisis after World War II. The new face starts altering Okayama’s identity, effecting his sense of morality. The film incorporates the story of another woman, unfolding before the eyes of Mr. Okuyama on the cinema screen. Presumably a survivor of the atomic bombing, she asks her brother if he remembers the sea of Nagasaki. She too is ashamed of the scars and disfigurement she bears. In The Face of Another, life proves to be the true masquerade. You can find the film on the Criterion channel.

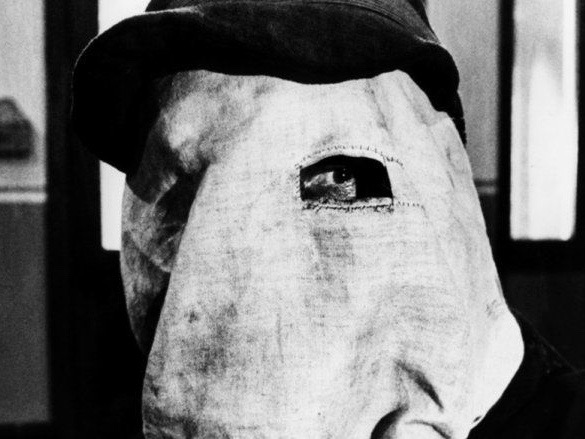

The Elephant Man (David Lynch, 1980)

In The Elephant Man the disfigured face breaks out of its concealment with delicacy. David Lynch’s sophomore film chronicles the real-life story of Joseph Merrick, a man who lived in 19th century London and whose heavily disfigured body and head were a cause for spectacle at the time, exhibited in freak shows in front of a crowd of onlookers to draw currency from their shock and horror. In the film Merrick, who is played by John Hurt, is “saved” from his merciless proprietor, Bytes, by Doctor Frederick Treves (Anthony Hopkins), who initially also succumbs to the temptation to display him for medical purposes and make a name for himself. However, after a while a friendship develops and the less and less frightened Mr Merrick gradually opens up to the world, even though the gesture is only rarely met equally. Lynch’s ability to conjure the uncanny does not reside in the disfigurement of the familiar as we might expect. Instead, it resides in the human gaze and in the way we shy away from looking at the unknown and the unfamiliar. In The Elephant Man, the only one who really dares to look it seems is John Merrick himself, and where he looks he finds beauty. The film can be watched on Orange, LaCinetek, Netflix and UniversCiné.