Bruce Baillie (1931-2020)

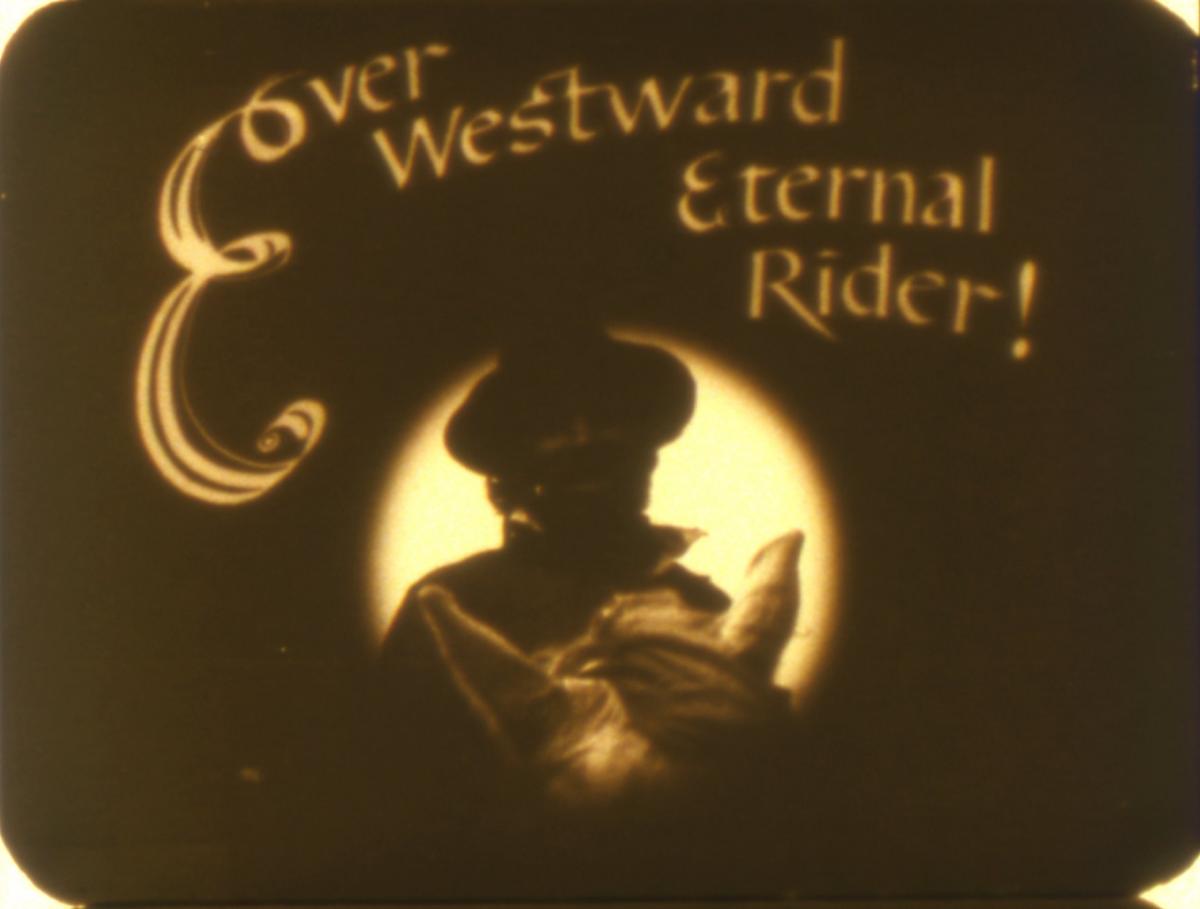

“In Quick Billy (1971), at the end of the film, we see Bruce Baillie himself riding off into the unknown – the eternal rider, superimposed upon the map of the United States. So he rides through the wide spaces of the country, through the wide spaces of his memories, dreams, childhood, friendships, and we who correspond sometimes with him, we do not even always know where he is. He seems to be always on the road.” – Jonas Mekas1

The American filmmaker Bruce Baillie has passed away at the age of 88 on Good Friday, April 10. “Baillie’s lyrical and keenly observational work evades genre and explores narratives in nontraditional forms – from short films to longer explorations. (...) His work has been inexpressibly influential to the world of avant-garde cinema, and his role as founding member of both Canyon Cinema and the San Francisco Cinematheque speaks to his importance in creating spaces and systems of support and distribution for experimental filmmakers.”2 A fusion of the mystical and the mundane, the cosmic and the personal, mythology and autobiography, his outstanding work as an artist equals his legacy as a distributor and promotor of avant-garde filmmakers. His film Castro Street (1966) was selected for preservation by the United States National Film Registry in 1992.

“Despite his sophistication, Baillie remains an innocent; the whole of his cinema exhibits an alternation between two irreconcilable themes: the sheer beauty of the phenomenal world (few films are as graceful to the eye as his, few are as sure of their colors) and the utter despair of forgotten men.”

P. Adams Sitney3

“In my filmmakers' pantheon, Bruce Baillie takes a shining place. His work I can see again and again. There is in Bruce Baillie something that reminds us of the wide country, of the spaces of America. I remember Baillie for certain images that keep reappearing in my mind. Curiously enough, those images have always to do with travel, with cross country rides, with wide spaces, with the huge American continent being crossed... In the images of his films, he seems to be very stable and very sure and always going after some definite and, probably, always the same image. With each film one feels maybe he found it. But no, the image of the dream is not yet caught, still somewhere else – so he makes another film, trying to come closer to it, from some other angle.”

Jonas Mekas4

“I was lucky to see his films in 16 mm. This was such a religious experience, almost, because the way he controls the lights and colors is so organic. Later, I found out that he sometimes developed his films himself or that he sent specific instructions to the lab, and that’s so admirable. Especially now that everything is automatic. I would call watching his films ‘religious’ because they are so profound and it’s like watching the wonder of nature. (...) It’s a reminder of beauty… Sometimes there’s a narration you have to deal with [as a filmmaker], but Bruce allows you to free yourself of that narration. When I look at Quick Billy (1971), I often think it’s like another, totally different chapter of Tropical Malady (2004). Even though I saw it after I made Tropical Malady.”

Apichatpong Weerasethakul5

“In 1961, filmmaker Bruce Baillie performed the insanely innocent gesture of hanging his now-legendary bed sheet in his mom's front yard in Canyon, California and put on a film show for his friends. He did it a few more times, drew some more people into it, and from coalescence formed a peripatetic film screening series, a correspondence journal (The Canyon Cinema News), a filmmaking collective and an distribution hub of experimental film. Both San Francisco Cinematheque – which has presented thousands of film screenings since then – and Canyon Cinema – which distributes and stewards 3,000+ films by over 300 artists – trace their origins to this originary screening.

Bruce's films are masterful and epitomize the west coast/northern California of the '60s era in their rich lyricism and themes of questing spirituality. Baillie was a master of hand-held 16mm camerawork, a master colorist, an astounding film editor and (again) a master of "a/b" printing and superimposition (see, for example, Castro Street). Not much is said about his work with sound but his soundtracks are often amazingly crafted – one day when I worked at Canyon Cinema, co-worker David Sherman and I listened to only his tracks as someone was previewing work in the screening room and we were blown away. I believe Bruce – who basically lived a wandering life of self-selected poverty – just did these tracks by fading between two 1/4" tape decks which is just amazing.”

Steve Polta, artistic director of the San Francisco Cinematheque in a social media reaction

Below:

Bruce Baillie with Robert Gardner on Screening Room in April 1973

All My Life (1962, 3')

Castro Street (1966, 10')

Quick Billy (1971, 55')6

- 1Jonas Mekas, “Bruce Baillie, The Eternal Traveller,” Movie Journal, April 1, 1971.

- 2“All My Life: The Films of Bruce Baillie” retrospective curated by Garbiñe Ortega at Film at Lincoln Center's Art of the Real 2016. Part of this retrospective travelled to the Belgian film festivals Âge D'ôr and Courtisane in 2016.

- 3P. Adams Sitney, Visionary film: The American avant-garde, 1943-2000 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 183.

- 4Jonas Mekas, “Bruce Baillie, The Eternal Traveller,” Movie Journal, April 1, 1971.

- 5Apichatpong Weerasethakul, “Longing for Change. The Shifting Shapes of Apichatpong Weerasethakul,” interview by Bjorn Gabriels, Sabzian, June 1, 2016.

- 6Here's a video recording of Apichatpong introducing Quick Billy and discussing it with Baillie at The New Museum in New York in 2011.