When Microbes Are the Stars

An Undervalued Festival: That of Scientific Film

On the occasion of Éditions Macula’s recent edition of the collected works of André Bazin (1918-1958), Sabzian will publish nine texts written by the French film critic between 1947 and 1957, both in the original French version and the Dutch and English translations. Bazin is sometimes called “the inventor of film criticism”. Entire generations of film critics and filmmakers, especially those associated with the Nouvelle Vague, are indebted to his writings on film. Bazin wasn’t a critic in the classical sense. François Truffaut regarded him as an “écrivain de cinéma” [“cinema writer”], who sought to describe films rather than judge them. For Jean-Luc Godard, Bazin was a “filmmaker who did not make films but who made cinema by talking about it, like a pedlar”. In the preface to Bazin’s What Is Cinema?, Jean Renoir went one step further by describing Bazin as the one who “gave the patent or royalty to the cinema just as the poets of the past had crowned their kings”. Bazin began writing about film in 1943 and founded the legendary film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma in 1951, alongside Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and Joseph-Marie Lo Duca. He was known for his plea for realism as a crucial cinema operator. Film opens a “window on the world”, according to Bazin. His writings would also be important for the development of the auteur theory. He was an editor of Cahiers until his death.

For three days, the small screening room of the Musée de l’Homme was the scene of a peculiar film festival. The films presented were titled Electroconvulsive Therapy, Grasshoppers’ Sperm Cell Division, The Path Towards the Infinitely Small or The AC Sinus Curve. Under the diligent as well as spiritual leadership of Jean Painlevé, the International Scientific Film Association was holding its annual congress.

Contrary to what one might think, scientists and technicians were outnumbered at this spectacle, which was a lot less dry than laymen would imagine.

Even when they concern frog legs or the behaviour of a white mouse, certain experiments shown in the films are far more exciting than most scenarios of “great” movies. Also the film critics, who – alas! – know a thing or two about it, came to Jean Painlevé’s screenings to relax. They would all tell you that microbe love is much more gripping than the love of Myrna Loy and William Powell.

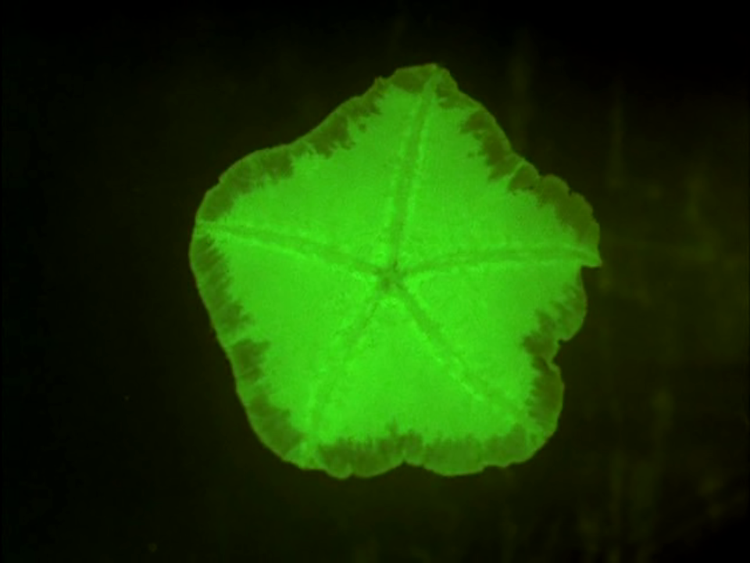

You need to see the ghostly ballet of “rotifers” in a drop of water or the underhand and implacable struggle of white blood cells against bacteria to have an idea of the plastic as well as dramatic possibilities of cinema.

This year, they presented an American colour film – which was awarded a prize in Brussels – on the bronchoscopy of lung tumours in which, thanks to a kind of tiny periscope slipped into the trachea, the camera was able to record the entire descent into the patient’s bronchial tree as easily as a tracking shot in an underground railway tunnel.

Of course, you sometimes need a strong stomach. In spite of Jean Painlevé’s cautionary advice to sensitive people, there was some fainting during certain surgical films.

That’s what happened on Saturday evening, when they showed an American film on the cosmetic facial surgery of people badly wounded in the war, which kept the attendants busy and made for the quick polishing off of a bottle of cognac planned for the occasion.

This text was originally published as ‘Quand les microbes jouent les vedettes. Un festival méconnu : celui du film scientifique’ in Le Parisien libéré, 953 (10 October 1947) and recently in Hervé Joubert-Laurencin, ed., André Bazin. Écrits complets (Paris: Macula, 2018).

With thanks to Yan Le Borgne.

© Éditions Macula, 2018