In the Shadows of Catacombs

A Conversation with Pedro Costa

This conversation took place in Ghent during Courtisane 2015. Pedro Costa was invited as one of the artists in focus of this edition of the festival, which screened several of Costa’s films and featured Cavalo dinheiro [Horse Money] (2014) as closing film.

Martin Grennberger: I would like to start with a question concerning the remarkable aesthetics of Cavalo dinheiro. Is the chiaroscuro effect connected to the fact that you’re using a camera that is not receptive for certain kinds of light?

Pedro Costa: With this kind of amateurish equipment, which is not technologically very sophisticated, it’s impossible to have the richness of detail of a 4K camera, not to mention the 35mm ones. And you start your work knowing these limitations. In a way, you’re a bit blind, like Stevie Wonder – the best musician ever – and you train yourself to ‘see without seeing’, and sometimes it forces you to make some very extreme choices. But I really wouldn’t call it ‘chiaroscuro’, it’s just a way of avoiding complications... It always begins as an attempt to be effective without losing the sense of the plasticity of the materials we are filming.

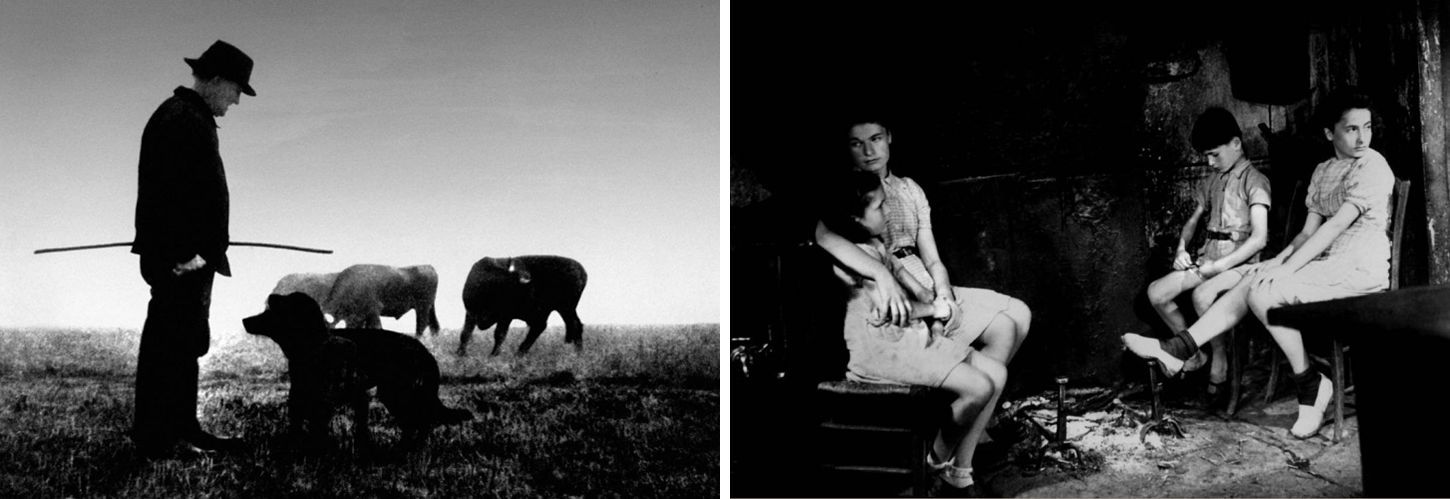

When Edgar Ulmer did Detour [1945] or Joseph H. Lewis did The Big Combo [1955], they made their choices: they knew they had almost nothing, they were working with leftovers – like we are – they knew they didn’t have the power to light up more than 30% of their frame and so they went for it full speed ahead… But these apparent limitations are the basis of all our work, which is to observe reality and to observe it in all its possible facets.

In No quarto da Vanda [In Vanda’s Room, 2000] I had just one source of light coming from a little hatch window and it was natural light so I had to study it closely. At eleven o’clock in the morning or at six in the afternoon, in summer or winter, I would know exactly where the sun would be. Few filmmakers begin their work with this preoccupation and even fewer need to have this knowledge. They don’t know their own room, they don’t care; it will be the director of photography’s job. Their dreams are more centered on: “Interior. Night. It rains. He wakes up in distress”. When I go into Vanda’s room or somewhere else my first task is to know everything there is to know about that place. I have to be prepared to do a scene here, to have Pango or Ventura sit next to Vanda and to have the light falling on him or her depending on what will be the necessity of the shot, the sequence and the film.

Stefan Ramstedt: While seeing Juventude em marcha [Colossal Youth, 2006] again now – and I’m especially thinking of one of the last scenes in the film in which Ventura is lying on the bed, having a bad dream – it seemed very obvious that the continuation would be Cavalo dinheiro. But I’m wondering how important the shooting and the making of Ne change rien [2009; Costa made a short film with the same title in 2005] was for the aesthetics of Cavalo dinheiro?

Lately, I’ve understood how important this small film really was for me. I had a great time and experience with my camera and I had a lot of pleasure lighting Ne change rien. I had to do this film a little bit faster than the others, which gave me room for finding solutions and trained me on how to solve practical problems, like adapting oneself quickly to a drastic change of light or simply figuring out how shots and sequences done on a considerable improvised documentary manner could work; practical things that in Juventude em marcha we had time to think about and work on, without any haste: the shooting took one year. It was not like we were staling and being lazy, but if we couldn’t find a solution one day, we could try it again the following day. With Ne change rien I had to find it right there, on the spot. On the other hand, it was a film that dealt with music, a film with music from beginning to end. And the origin of Cavalo dinheiro was musical…

Ramstedt: Vitalina, the new person you work with, speaks in a peculiar way, she’s kind of whispering her lines, and I think you’ve said that the reason why she whispers, or rather how it happened, was that she suddenly whispered a sentence during the shooting or the repetition. Do you still shoot a lot of material, and what kinds of decisions are taken during the shooting?

Yes, usually, we shoot quite a lot. That’s not because we are workaholics, it’s just that I need it, our little crew needs it, and the actors too. You know, repetition is not only a way of finding, it can be a way of thinking. Everybody knows that a film is very difficult to make, no one knows what will happen when you turn on a camera, no one ever knew what cinema is and the guy who’ll swear he knows it is a fool. So, you need to work, to research, you need to discover. The first time I met Vitalina, I asked her if I could film in her house, just inside the house. She said yes, and later we started talking and she kept whispering all the time and I had to ask her to repeat her phrases; she doesn’t speak Portuguese and even for me it’s hard because her creole accent is very tough. But I also think she was whispering not just because of some natural shyness, but because she was suspicious of me: she was afraid, being a stranger in a strange land and not having all her legal papers yet.

That’s what I think any serious filmmaker should do in the first place: to understand – why is this creature whispering? Because she has no documents, she’s an illegal immigrant. We’re helping her now, it has been a nightmare, these European bastards strive on making our lives miserable. But to talk like that in the whole film meant that she had to work her voice, her posture, the tone, the volume, and she’s not used to it. It’s a very difficult thing, even for a professional: to talk softly and low but in a way that can still be clearly understood and caught by the microphones, and to do it without losing feeling and purpose. We all know that people on the margins of society, ‘the other half’ like Jacob Riis used to say, immediately lower their voices when confronted with the authorities; they whisper not to be caught; they spend their existence in hiding; she’s coming from far away and her whispering is almost a voice without a body or a body with a strange, broken, faded identity.

I’m really proud of the work she did, and I’m really fond of this idea. I think we did well in materializing a social, political violence through this form, through this metaphor of a plaintive sotto voce. Perhaps next time she won’t have the need to whisper and she will sing: “My passport and me…”. It’s difficult to explain all the moments we’ve been through on this work, all the days spent on research, testing, failing, building up again, failing again. With Ventura it has become a bit smoother, he’s very, very sharp and quick and we already know each other a bit better. Yet, there are lots of things that are common to everybody who works in film: the same rituals, the same procedures.

Grennberger: There’s an intriguing song in the film. Ventura and Benvindo don’t agree on the lyrics, and you can see Ventura smiling, but it’s very subtle. Are there a lot of laughs during the shooting?

Well, sometimes… A lot of our ‘actors’ are very funny. They are ‘characters’ like the saying goes. Ventura is a very witty man. But, in fact, that sequence was one of the most painful scenes we ever did. But it’s nothing that we didn’t suspect, just read Jerry Lewis or Buster Keaton interviews or writings: these comedians’ working life was hell, a real torture. And Chaplin was probably the most troubled one. That scene was really one of the most difficult, exhausting scenes. We had to rehearse and shoot it for days and days; but you don’t get these kinds of things without some blood, sweat and tears. It’s not very different from those directors I was mentioning, who killed themselves trying to get rhythm and tone right, tempo and form together… And you must understand that Benvindo who’s pestering Ventura about his mistakes singing the song never had any kind of experience or relation to theater or film… perhaps a little bit with music. And he’s a recovering alcoholic and an epileptic…

Grennberger: Your use of the Riis photos in the film is striking.

I’m still not sure, sometimes I ask myself if that opening didn’t need a bit more time, or less, I don’t know... It’s very difficult to edit these kinds of materials: photographs, documents. I’ve heard Danièle Huillet talk about it, and on this occasion I really felt it myself, I was confronted with the same problem. She said that it’s very difficult to edit, to cut pieces of film which are ‘emptied’ of human movement, shots without human beings moving, talking, acting... Danièle was referring to the difficulties she experienced in the montage of a film called Trop tôt/Trop tard [1982]. To cut landscapes or, for that matter, photographs, is really one of the hardest jobs.

Grennberger: Why is that? The absence of human beings in the film…

It’s because of the lack of movement. Because of the absence of the dynamics of action and reaction. Because reading the movement of a man running or a woman talking is not the same as reading the movement of the waves in the ocean or the story of a family in an old photograph. In film, in a way, you don’t understand a mountain. You don’t communicate with the ocean unless you’re…

Grennberger: Godard.

Godard, or a surfer monk… But I’m not Godard, or a monk. It’s about movement, human movement; it’s a connection. It’s difficult to read the movement of a mountain. Its beginnings are out of our sight, deep in an abstract region very far from our time and comprehension, hard to relate to. Where does it start? A shot of a mountain, we could say, always begins and ends in spite of the mountain, it always derives from a narrative, a story that is exterior to the mountain. In film, a landscape is always, more or less, decorative and a photograph is, more or less, a document… Every human movement has a beginning and an end. You can interpret photographs any way you like, you can always say that they’re alive, that they talk and speak to you, etc., but in fact, they’re silent, they don’t move, they’re frozen. So it becomes a little bit arbitrary, when do we cut? Another problem is that every time you bring two images together, they immediately begin to tell a story, and I didn’t want that. I wanted the opposite, I wanted them to be what they really are, pictures representing something, someone, some place, a situation. Our suspicious minds work like that, and I didn’t want them to begin imagining right away. So I was trying to present them in the most unintentional way. It’s always very difficult to avoid intentions.

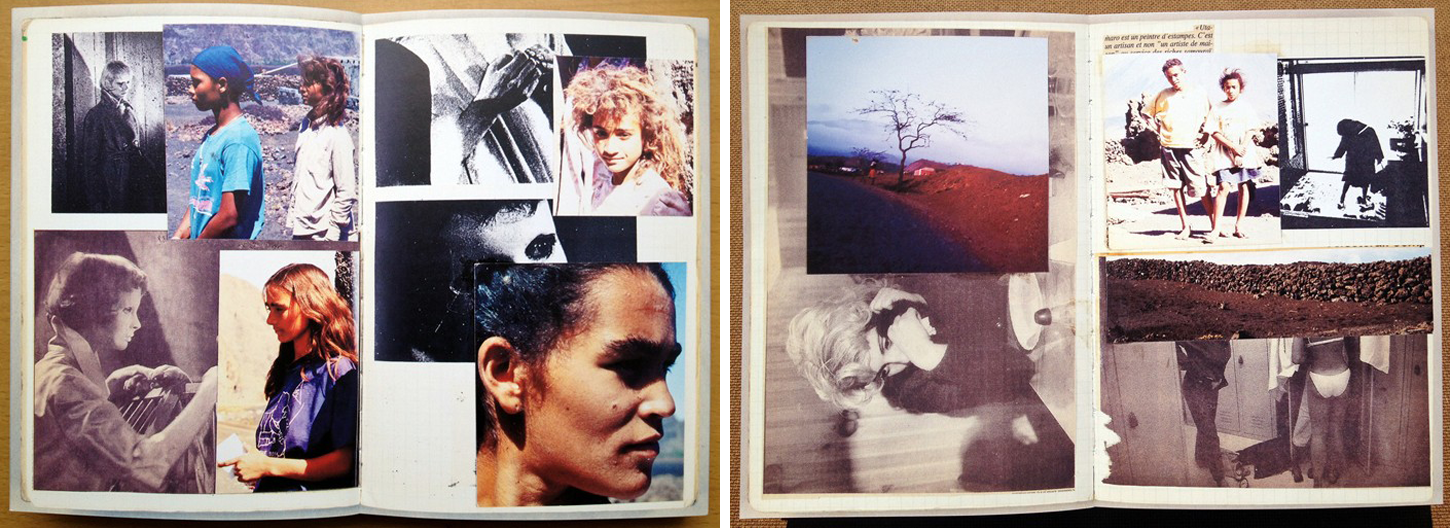

Ramstedt: When the production notes of Casa de lava [1994] were published, were you afraid that you would reveal too much of your own, let’s say, intentions? You seem always to be very conscious of what you’re saying about your work.

A long time ago I used to be more strict, but I don’t mind it anymore, it’s becoming part of the patrimoine. There are certain things that belong to us, and perhaps you should share them, in the sense that they’re here for us to use. For instance, there’s a painter that I really love, Jacob van Ruysdael, one of these great guys from the Low Countries who painted almost nothing but landscapes, valleys and woods, fields with windmills and cows. I make films with problematic girls and boys in bedrooms, I prefer moving in the shadows of catacombs, so why do I admire this guy so much? His works are fuel or fresh air, they’re like a drug for me. It’s difficult to explain… I know these images must also work on a subconscious level, there must be some kind of feeling or phantom of a lost, ancient, better time, a better world… I share Straub’s notion of ‘communism’: we should appreciate and protect and fight for the earth we live on. It’s probably because I’ll never have a cow in one of my own films that I love van Ruysdael so much. Just think about all the things we are losing every day, it’s unbearable. I’m a bit afraid because I've been seeing the effects on people. That’s what I’m showing in my films.

Grennberger: You’ve talked about the problem of the notion of realism these days, and that your last film tends toward a certain form of – you use the word ‘theatre’ – but also of a new understanding of the ‘musical’. Could you say something about the problem of realism and how you try to solve that in your own work?

I don’t know if it’s a problem for people. I guess not. For me, it’s about trying to live and work inside this routine. I’m stuck in a tradition, like an employee of a studio that used to have schedules and rules, a place that worked to fulfill certain needs and desires. And those needs and desires are not that important anymore. I think you will agree if I say that this world is not about progress or development and it’s not really getting better all the time… it’s about losing and losing every day. My Cape Verdean friends are constantly mourning: “We are losing the words, we are losing the rituals, and we are losing the respect for our ways of being”. The little kids don’t have it in them anymore: I used to see young boys and girls walking by the old ladies and ask for a ‘blessing’. It happens less and less. That’s loss. I’ve been at celebrations in the new neighborhood, communal barbecues with hundreds of people, and when the moment comes for them to eat some fried chicken, it’s like a feast, especially for the kids… I mean, fried chicken was their usual dinner in the old days. Now they’re probably eating rice and potatoes day in and day out, less meat, less fish. That’s because of the loads of money they’ve spent, the money they were forced to spend on all the stuff they see on TV, by the traps laid in front of them by the banks. Or perhaps because of the pretty picture they see at the bourgeois apartments that all the Cape Verdean women come to clean every day, an image that they want to replicate in their own homes… Who can blame them? But what a loss! It’s a cruel, cold reality.

It seems to me that we are losing an incredible amount of things that are vital to go on telling the tale. I mean, me being someone who believes in narration. This is the catastrophe we’re facing. We’re left with nothing else but words, with the power of words. I’ve always had a great belief in them, much more than in images. When I say ‘the power of words’, it’s not like there’s a secret meaning to it. Remember the letter in Juventude em marcha? Do you know the sad story of the last days of the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam? The KGB was coming to his apartment to arrest and deport him to the gulag. In a frenzy, he begged his wife to memorize his poems so that the police wouldn’t get hold of them. He could no longer write them down, do you understand? Perhaps you’ll disagree and say it’s not yet that tragic; but I’ll tell you that if we don’t grab the words now, they will be taken from us. And the feelings too. Then there will be no more films. We’ll have to grab the words quickly because they are being kidnapped. Our people are going mute, amnesic and insane. Our people are being imprisoned and impoverished. The working class – what we used to call the working class – is handicapped, autistic, confused. Insane.

Grennberger: In what sense do you use that word, ‘insane’?

It’s an illness. They can’t find work, they can’t find their train of thoughts, their memory. They are losing the ability to love, they can barely breathe…

Grennberger: But do you regard the use of the word, in your specific way of approaching it, also as an act of resistance? Like preventing the robbery of that word?

A long time ago we used to say that we are exploited or alienated. Now I would say that the people are going out of their mind, they are becoming schizophrenic. Besides being an epileptic, Benvindo is totally confused; I’m not even mentioning the alcohol because that comes at birth, like an indisputable condition. One needs memory to go on surviving, resisting. It’s really tragic, and in my work I’m confronting this every day, I mean, I’m beginning to work with that loss of memory, that loss of energy, that loss of hope. Some films must be made to fight it.

Grennberger: In Cavalo dinheiro there is this strict use of the song, or of certain ruptures of music, which is very powerful. You said before that you are careful about not wanting to make it too powerful and that you really want to keep it tight. I’m thinking of the organ piece by Olivier Messiaen that you use.

I’ve already revealed that I was preparing and that I was going to do the film with the collaboration of the musician, composer and poet Gil Scott-Heron. We had just formulated some ideas and then he died and the dream was cut short. When we first talked, Scott-Heron and myself, we agreed that the film could be a sort of long prayer… We thought we needed prayers… It was going to be an oratorio sung by Ventura and then picked up by Gil himself or Vitalina or all the other voices. It would be polyphonic. In what shape or form, I cannot tell you. This revolutionary soldier who confronts Ventura, who talks with a lot of different voices, ‘speaking in tongues’, without ever opening his mouth, is probably an example of what remains from the original idea, a clue for some of the elements that would have been at play. And perhaps that first project would have insisted even more than this one on the power of words, the enchantment of the litany, the spoken lament. And also on the sense of loss, the feeling that we will have to compose more and more with what’s left, with broken people in a broken world. And knowing that we should always avoid things that we don’t need, that the film doesn’t need.

Grennberger: Do you always have a sense of what the film does not need? Is that something intuitive?

You get there, slowly. Making film after film with the same people, growing older while filming with them, makes you very aware of what we need and what we don’t need. It’s a question of continuing to adjust the balance. On a plain material level, as a working, researching unit, we don’t need that much. I was taught to do a film with a lampshade and a bouquet of flowers. It was the good old JMS/JLG school [Jean-Marie Straub/Jean-Luc Godard].

And then we confront problems that arise from our confinement. And when we solve some of those problems with a maximum of effectiveness, it becomes a very special moment in our work. Already in Juventude em marcha there were are a number of small audacities and conquests...

Grennberger: During the Q&A the other day you talked about the importance of narration, about what you miss in contemporary cinema. I got the impression that cinema is like a grammar of gestures for you. You said that you never see someone opening a door in contemporary cinema, you don’t see people sitting at the table having dinner.

I was not talking from an humanistic point of view; it’s not that I cherish human beings having dinner together and being nice to each other. It’s just about sound and image and life and reality. Opening a door, in a film, not only is it very difficult, it has always been very difficult, even in the old days. When you watch a film like Farrebique [Georges Rouquier, 1946] you see a lot of things, there is an incredible number of things you see per second and they were there, they existed. That’s the most incredible thing; everything existed on the screen. I don’t know if it’s just me, or the power of documentary, or life being so raw... I think we’re losing a lot of stuff, every day. We’re losing the ability, the craft, we don’t know how to use our minds and our tools – myself included. What we see mostly today is a million ways of escaping a confrontation with reality.

Ramstedt: I was thinking about another thing you said at the Q&A, about Rivette discussing Capra’s It Happened One Night [1934] and saying that contemporary films needed to be much longer. I’m wondering if you think that his arguments are still valid today?

Absolutely. Rivette was talking about the scope of emotion, the amazing roller coaster of contradictory feelings, the immense horizon of events that these classical directors could deal with in just a normal feature film of 90 minutes… It’s really a lost art. “Once there was a formula”, like Talking Heads sung… The love for craftsmanship, the art of writing, the finesse of the performances, the brilliance and the efficiency of the directing, the emotional extravaganza that these guys could fit into 90 minutes is unthinkable nowadays. To do the same thing today, to achieve such a construction with all that complex layering, it would take any contemporary director 3, 4, 5 hours of film. Just to get to that crucial moment when the girl or the boy breaks down, it would take any of us at least 3 hours…

Of course, then it was more simplistic, black and white; a black and white simplicity that kept forging American democracy. The world was watching, dreaming about that, and, that way, because of cinema, the world was fairly understandable. Now, just think about Warhol for example. If you take a film like Chelsea Girls [Paul Morrissey & Andy Warhol, 1966], you have Nico in the kitchen just talking to this guy and combing her hair for hours, just rambling on. And it’s not enough to ease her pains… No quarto da Vanda is a lot like that. Just to get a bit closer to Vanda’s sadness, I know I’ll need a lot of time.

Grennberger: Do you have a clear sense of the time scale, or is that something that evolves during the process, that happens while working?

It’s not a matter of improvising; it’s following reality. Sometimes elements from life come into the picture and can enrich our invented things. Some nightmare, a preoccupation, a recurrent pain, can always find its way into the film, in one form or another. I guess these elements are difficult to be welcomed in a normal production: even if somebody is ill or not feeling well, they’ll have to shoot. It’s a ruthless machine. If Ventura or Benvindo are not well, we won’t shoot. Like Godard used to say, “If an extra is ill, I won’t shoot”. Anyway, in our films, no one’s an extra. You have to work on your schedule, prepare your daily plan with a different attitude, with a point of view.

Ramstedt: You’ve been speaking about your background as a student of history here during the Q&A’s, and I’m wondering if you would think it problematic if people used a concept like ‘counter-history’ in relation to your work? You have been talking about that as a concept, although you didn’t use the term.

I just thought that the interesting way of seeing things was like some historians, anthropologists, philosophers do, who were redefining the class struggle, the structure of class relations. It has always been of some use to me, not only when I was in school, but later when I became interested in cinema. I think it helped me not losing track.

Grennberger: Talking about philosophy, how do you feel about the attention you’ve attracted from a philosopher like Jacques Rancière, who’s written quite a few essays about your work? You seem to resist a certain form of rigid philosophy.

I like and admire his work. I still think his La nuit des prolétaires [Nights of Labor, 1981] is the most important work of the last 30 years. Writing about my films, sometimes in a very flattering way, he’s been very insightful. He found an extraordinary idea about this last film, Cavalo dinheiro, a formula that applies to the long scene in the elevator: “the narrativisation of space through the noise of time”. You see, sometimes – not often – it’s still possible to feel a certain speed, an illumination, a kind of light shining in a text about cinema. There’s Rancière, but also Narboni, Eisenschitz. Thom Andersen is a very good writer. Rosenbaum, Chris Fujiwara.

But I have the feeling that it’s a vanishing breed. More and more we’re surrounded by all these pathetic film studies; ignorant teachers rambling on and on about very superficial things. It’s the kind of sauce that can put out any inner fire or passion for cinema. I’m sorry, I’ve always suspected a lot of theories applied to cinema. I began watching films seriously and passionately in a moment when the ‘do it yourself attitude’ ruled. It was a time of action as opposed to a time of reflection; it was about practice, it was about doing it and – stupidly – not stopping too much to think about it. And my studies were of history, a discipline intimately connected to reality. It’s obvious that my films are related to Jacques Rancière’s researches. The delirious, nocturnal, poetic world of these marginal people…

![(9) & (10) Cavalo dinheiro [Horse Money] (Pedro Costa, 2014) (9) & (10) Cavalo dinheiro [Horse Money] (Pedro Costa, 2014)](http://www.sabzian.be/sites/default/files/Cavalo%20dinheiro_02.png)

Ramstedt: Thom Andersen used the word ‘aristocrats’ to describe the people in your films, and I understand why he would do that, but do you agree with that kind of romanticism?

I don’t mind it. It’s a nice way of putting it. It’s serious observation. If these people come out so noble and so righteous, so tall, I guess it’s not only because of the magic and tricks of cinema, it must be because of themselves, because of the beauty of their bodies and souls; it’s not only me wanting them to come out as kings and queens, they are kings and queens.

This interview was first published in Swedish on Magasinet Walden, a digital platform for various forms of film criticism. Stefan Ramstedt and Martin Grennberger are editors at Magasinet Walden. They would like to thank Christina Stuhlberger for her generous assistance in making the interview possible.

Image (1) from Detour (Edgar Ulmer, 1945) and (2) from The Big Combo (Joseph H. Lewis, 1955)

Images (3) and (4) from Trop tôt/Trop tard (Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, 1982)

Images (5) and (6) from the production notes of Casa de lava (Pedro Costa, 1994): Pedro Costa. Casa de Lava - Caderno, Pierre von Kleist editions, Lisboa, 2013

Images (7) and (8) from Farrebique ou Les quatre saisons (Georges Rouquier, 1946)

Images (9) and (10) from Cavalo dinheiro [Horse Money] (Pedro Costa, 2014)