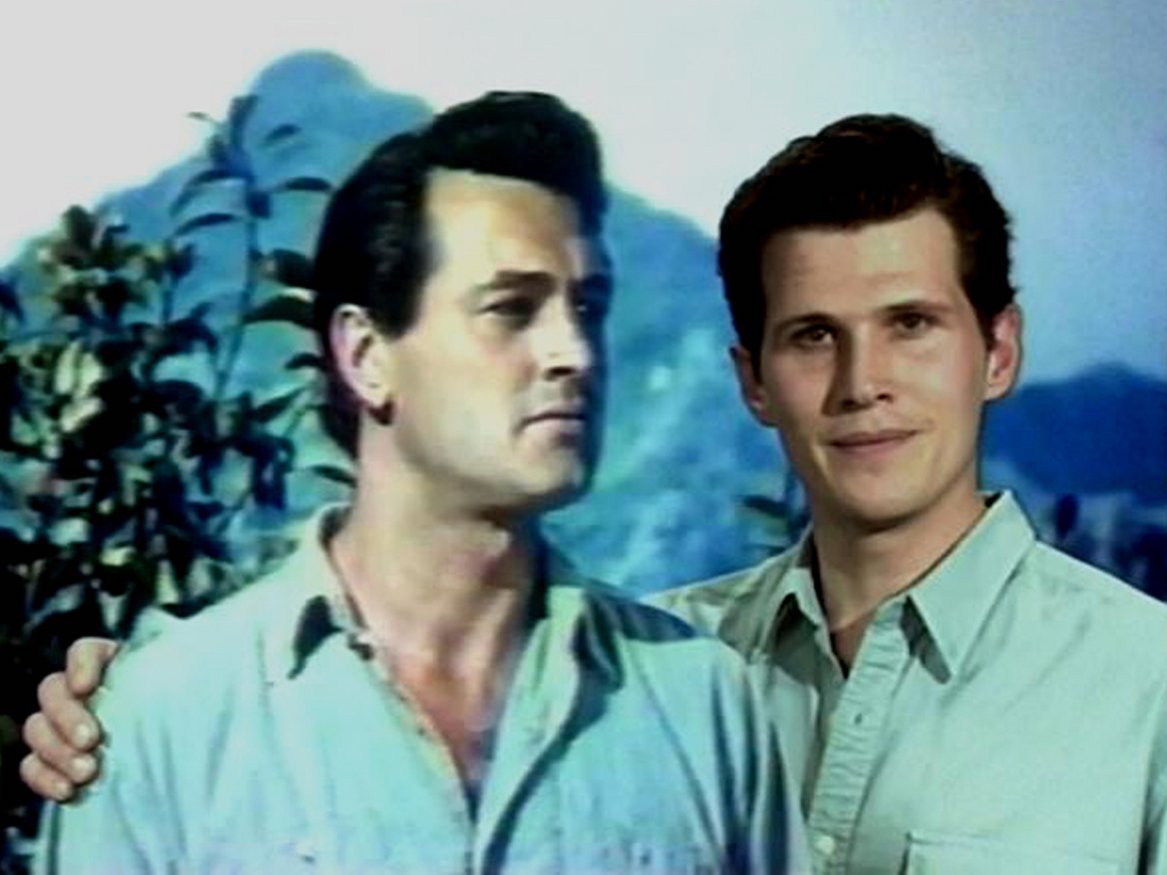

Rock Hudson’s Home Movies is a collage film, in which the ‘found footage’ is the star. It is revisionist film history that reexamines Rock Hudson’s films in light of what we now all know about him – namely, that he was gay and died of AIDS. He is a prism through which sexual assumptions, gender-coding, and sexual role-playing in Hollywood movies and, therefore, by extension, America of the 1950s and 1960s can be explored.

Mark Rappaport

In the interest of truth and justice, I have set down the unvarnished facts of my life – my own story in my own words.

And especially in the images of the movies I was in.

Let people judge for themselves.

Rock Hudson opening Rock Hudson's Home Movies

It was all up there.

Rock Hudson

You were a great star, Mr. Hudson – one of the biggest. Sorry it all had to end like this.

Director Mark Rappaport’s voice at the end of Rock Hudson’s Home Movies

“Addressing the medium no less than the actor, the movie is an act of criticism… and love, investing the image ‘Rock Hudson’ with a pathos only barely evident in Hudson’s original imitation of life.”

J. Hoberman1

“Rock is a unique paradox – the paradigm of screen masculinity who also happens to be gay.

The only effective way to confront and critique popular culture is by presenting it in the forms and images in which it first presented itself, not by providing a second-hand description of it. As important for me in making Rock Hudson as the issue of representation – especially in the areas of gender role-playing, masculine/feminine, straight/gay, etc. – is the ability to show the footage under discussion. When someone writes an article about representation in film, you have to rely on your dim memories (that is, if you've seen it and if you remember it at all) and on their description of what they were seeing. If they are describing several examples, they are making the connections for the reader. In my format, you bring the source to the spectator. Even if the scene is out of context, the authenticity of what is presented, what is seen and heard, is undeniable. You are not subject to the additional, and unreliable, barrier of a secondary source's impression of whatever it was they think they saw.

To say that films reflect reality has always been a half-truth at best. If the relationship between screen and spectator is an endless hall of mirrors reflecting expectations, received ideas, false myths, and the desire to embrace them, in one way or another the cycle must be short-circuited. Rocks must be hurled into this gallery of endlessly reflecting mirrors – the screen, the audience, the audience, the screen...

I [am] using the structure of a fictitious autobiography (that nevertheless has real underpinnings) to examine contemporary social attitudes and mores and to explore the peculiar ways that private lives are revealed in an unashamedly public medium. I sift through dozens of films looking for details that illuminate a larger picture [...]. The search for the revealing scene or shot is part of the process in revisionist film history in which all films are artifacts in a densely layered archeological dig.”

Mark Rappaport2

“Mark Rappaport – one of our finest independent filmmakers, a writer-director essentially forced into silence by the evaporation of state funding until he discovered video, has created [...] a work of radical historiography that seeks to convert us from passive to active spectators, the 63-minute Rock Hudson’s Home Movies. [...] But Rock Hudson’s Home Movies is even more a work of film criticism than of film history, though this is criticism couched in the form of pseudoautobiography. [...] The most persuasive critical tool Rappaport uses, and one that would never work as well in print, can best be described as indexing: piling up examples of behavioral or thematic motifs from different films that immediately and fully demonstrate whatever generalization is being made. [...] Rappaport plays his new brand of film criticism like a grand organ, periodically freezing and unfreezing the images, whether to concentrate on certain visual details or allow the spoken commentary to dominate. With a great deal of acuteness and dexterity – he’s especially adept in the editing – he begins to show some of the exciting possibilities inherent in this new form. Showing us a way to talk back to the movie mythologies that influence and often corrupt us, even to the point of poisoning our dreams, he suggests that we don’t have to be millionaires or commandeer a television network to enter into a dialogue with the crushing Hollywood machine. At the bare minimum all we need is a will, two VCRs to play with, and something trenchant to say.”

Jonathan Rosenbaum3

“[L]ike comparable video-based film history essays, such as Mark Rappaport’s Rock Hudson’s Home Movies (1992) and Chris Petit’s Negative Space (1999), Jean-Luc Godard's Histoire(s) du cinéma ended up integrating the diminished, murky quality of the film image, mediated through electronic reproduction and repeated copying, into its discourse on technological change.”

Michael Witt4

“In zijn films was Rock Hudson (1925-1985) de vleesgeworden stoere heteroseksuele Amerikaanse bink. Pas toen hij aan aids leed, maakte hij bijna noodgedwongen zijn coming-out. In zijn stimulerend filmisch essay vertrekt de Amerikaanse onafhankelijke filmer Mark Rappaport van de ‘gay subtext’ in Hudsons Hollywoodfilms. Via raak gekozen en slim gemanipuleerde fragmenten uit zijn suggestieve pyjamaspelletjes met Doris Day en melodrama's van Douglas Sirk wordt de leugen van de droomfabriek op grappige wijze ontmaskerd. Via een lookalike acteur blikt ‘Mr. Beefcake’ zelf met droevige humor terug op zijn carrière. Dit is tegelijk een mooi eerbetoon aan de man die meer dan wie ook aids in de Reagan-jaren bespreekbaar maakte, een geestig revisionistische geschiedenisles en een scherpzinnige exploratie van de kloof tussen de mythes van de commerciële cinema en de verborgen waarheden van het echte leven.”

Patrick Duynslaegher5

- 1Jim Hoberman, “Rock Hudson's Home Movies,” The Village Voice, March 2, 2011.

- 2Mark Rappaport, “Notes on "Rock Hudson's Home Movies,” Film Quarterly, 49 (4), 1996, 16, 22. This article is abridged from a longer version published in volume 12 of the French journal Trafic (Fall, 1994).

- 3Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Rock Criticism,” Chicago Reader, November 20, 1992.

- 4Michael Witt, Jean-Luc Godard, Cinema Historian (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013), 22.

- 5Patrick Duynslaegher, “Rock Hudson's Home Movies,” Film Fest Gent catalogue, 2016.