An old villager deeply in love with his cow goes to the capital for a while. While he’s there, the cow dies and now the villagers are afraid of his possible reaction to it when he returns.

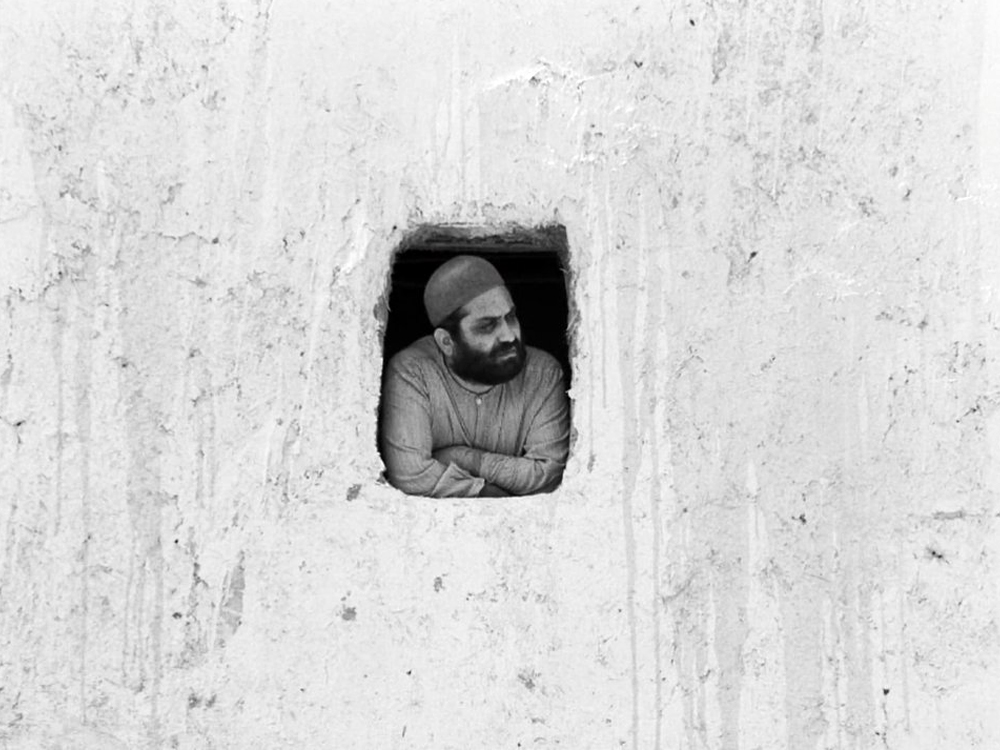

“The silhouette of a four-legged creature emerges over an indistinct horizon. As it moves, it splits apart and merges together a few more times, revealing itself to be a man and his cow.

This sequence, presented in a series of black-and-white negative images, comes at the start of Dariush Mehrjui’s pre-Iranian Revolution landmark The Cow, (...) an adaptation of Gav, by writer and playwright Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi, it’s a film of unstable, amorphous identity, for which that suggestive overture soon becomes emblematic. But given its ever-shifting borders, this portentous, almost phantasmic image also carries a different, if more banal sort of implication, pointing up to the problems endemic to narrativizing any cinematic movement – in this case the Iranian New Wave, of which this film is considered a pioneering work –amidst problems of state censorship and limited theatrical distribution.”

Lawrence Garcia1

“It is not only the story of the singular relationship between Hassan and the cow that provokes the film’s examination of the boundaries of acceptability within a community, but also the imagined relationship the village holds with a group of people who live beyond its borders. These “others” are simply referred to in the film as the “Balouris,” and their name is called forth whenever there is a crisis in the village. Theft, vandalism, assault, and violence are all imagined as the province of the Balouris alone. The villagers’ fear is expressed by Mehrjui in the way he frames the Balouris: often depicted in a long shot, standing at the top of a small mountain, their silhouettes menacing against the pastoral landscape within the village’s boundaries.”

Sara Saljoughi2