One family’s destiny, rhythmed by the course of nature, the changing seasons, the life of a river.

What works in recent years, then, in cinema or otherwise, do you see as having shifted something in the perception of the present?

Jacques Rancière: In the last few years I have been able to get this feeling from the films of some young Chinese filmmakers. An Elephant Sitting Still (2018), for example, the only film by Hu Bo, a filmmaker who committed suicide at the age of 29. Or Kaili Blues (2015), Bi Gan’s first feature film, or Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains (2019) by Gu Xiaogang. I have the feeling that these films say something, in a palpable form, about time, memory or amnesia in China today.

Quelles sont les œuvres alors, au cinéma ou ailleurs, qui ont pu selon vous, ces dernières années, faire bouger quelque chose de la perception du présent ?

Jacques Rancière: Ces dernières années, j’ai pu avoir ce sentiment devant les films de quelques jeunes cinéastes chinois. Par exemple An Elephant Sitting Still (2018), l’unique film de ce cinéaste qui s’est suicidé à 29 ans, Hu Bo. Ou encore Kaili Blues (2015), le premier long métrage de Bi Gan, ou Séjours dans les monts Fuchun (2019) de Gu Xiaogang. J’ai le sentiment que ces films disent quelque chose, dans une forme sensible, sur le temps, la mémoire ou l’amnésie dans la Chine d’aujourd’hui.

Interview with Jacques Rancière by Mathieu Dejean and Jean-Marc Lalanne1

Considering you wanted to represent these rapid changes in the area, which were happening in real time, why did you elect to make a fictional film, rather than a documentary?

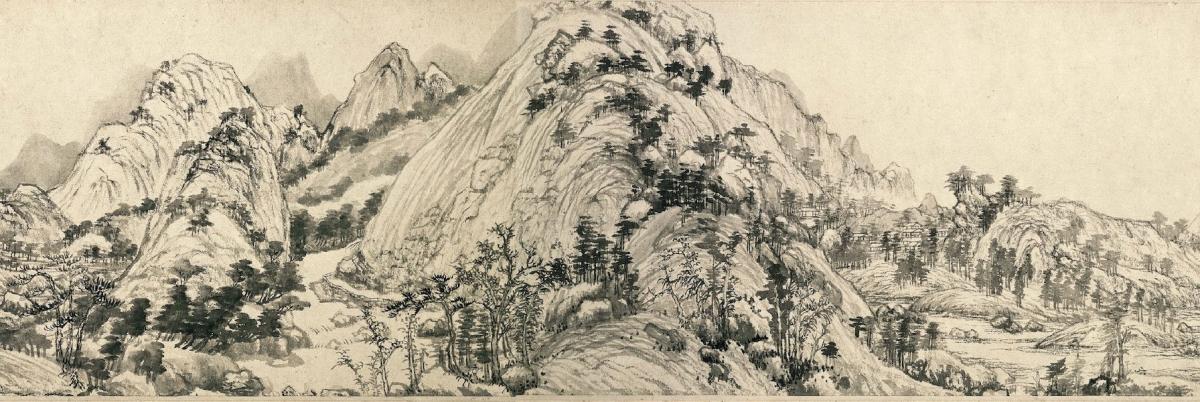

Gu Xiaogang: The film at first was inspired by an ancient Chinese landscape painting named “Along the River During the Qingming Festival”. And this painting technically-speaking is very good, but besides it also has a very high value of documentary–like record. It lets people commemorate or remember what happened in that time – how people wore clothes and how they communicated, how they sold things. This kind of painting inspired me a lot. Somehow it can explain why I chose to make a fictional film rather than a documentary. I wanted to employ a picturesque way of depiction. I wanted to use this film in a parallel way [to this type of painting], to show what happened during the present day. The film itself is only a medium to show these kinds of changes [that were going on in the town]. I wanted to try something new, using a new film language. So I chose a fictional film inspired by landscape paintings, rather than only documentary. Because it’s like a kind of brand new thing in film language, there weren’t that many references.

Such transference from one form to another always seems productive, or at least stimulating, opening up new possibilities for discovery, or even a new language as you say. No matter how hard you try to make a painting, it’s still a film, yet the impossible attempt yields something new. The genre of painting you’re referencing does have a documentary quality, recording the clothing of the era, the homes, and countless other observed details, but it’s also very narrative, and tends to be linear in the way that you look at it. You’re reading through it.

Gu Xiaogang: For the Chinese shen shui scroll painting – it’s not always [presented] like when we visit museums. It’s on a spindle, it’s a scroll. You need to open it slowly, and from right to left, giving it something like [the quality of] a film. It allows you to tell the story slowly, rather than just give you all of a sudden everything. For normal photos or pictures, we can see the space directly, immediately. But [in shen shui] you can see the eternity of time and infinity of space. Something like this. For a single shot, it’s not hard to represent things as a painting, or the feeling of a painting I want you to have. The question is how to make it feel like a painting in general, for the whole film. We discovered a new way of shooting – it’s about the emptiness of the landscape. When you open the scroll of a painting, you will see the landscape first. Then, when you take a closer look, you will see the characters, and other details. Then you will see the landscape again.

Interview with Gu Xiaogang by Eric Hynes2

Second section of the scroll painting Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains (1348-50) by Huang Gongwang.

Second section of the scroll painting Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains (1348-50) by Huang Gongwang.

- 1Mathieu Dejean & Jean-Marc Lalanne, “Jacques Rancière : ‘L’enjeu est de parvenir à maintenir du dissensus’,” Les Inrockuptibles, 15 février 2021. Translated into English as “Jacques Rancière: ‘The issue is to manage to maintain dissensus’,” Verso Books, 10 August 2021.

- 2Eric Hynes, “‘Time is a character’. Interview: Gu Xiaogang,” Film Comment, July-August Issue, 2019.