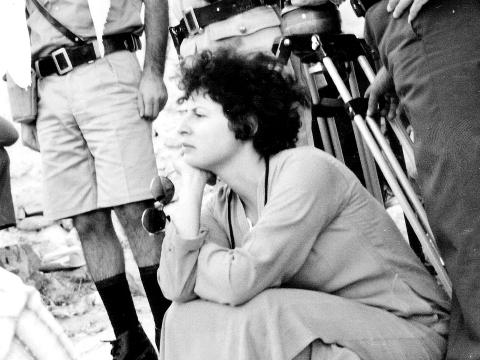

Heiny Srour

Out of the Shadows

Those of us from the Third World have to reject the idea of film narration based on the 19th-century western bourgeois novel with its commitment to harmony. Our societies have been too lacerated and fractured by colonial power to fit into those neat scenarios. We have enormous gaps in our societies and film has to recognize this.

Born in 1945 in Beirut, Heiny Srour studied Sociology at the French University of Beirut (Ecole Supérieure des Lettres) and went on to study Social Anthropology at the Sorbonne in Paris, where she was a student of both Marxist sociologist Maxime Rodinson and anthropologist filmmaker Jean Rouch. In 1969, while pursuing a PhD on the status of Lebanese and Arab women and working as a journalist for AfricAsia magazine, she discovered the struggle of the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf, which led an uprising in the province of Dhofar against the British-backed Sultan of Oman. Determined to make a film about this feminist movement, she spent two years doing intensive research and finding the necessary funds before setting out to Dhofar. From the Yemeni border, Heiny Srour and her team crossed 500 miles of desert and mountains by foot, under bombardment by the British Royal Air Force, to reach the combat zone and record the only document shot deep inside the Liberated Area. The Hour of Liberation was completed in 1974 and selected at Cannes Film Festival, making Srour the first woman from the Third World to be selected at the prestigious international festival. Including four years of restoration, this documentary took, all in all, ten years of her life. It took her six years to achieve her next film, Leila and the Wolves (1984), in which she unveiled the hidden histories of women in struggle, in particular in Palestine and Lebanon, by weaving an aesthetically and politically ambitious tableau of history, folklore, myth and archival footage. In her words: “Why shouldn’t women be ambitious? Because men only want women to exclusively deal with women’s issues like home, family and so on, they want to ghettoize us. I resent this. We should deal with the public affairs and political issues too.” Since initiating a feminist study group in Lebanon in the early 1960s, Heiny Srour has been vocal about the position of women, in particular in Arab societies. She has written and spoken extensively about the image and role of women in Arab cinema. In 1978, along with Tunisian filmmaker Selma Baccar and Egyptian film historian Magda Wassef, she co-authored a manifesto ‘For the Self-Expression of the Arab Woman’, remaining passionately active in her feminist advocacy to this day. More recently, she shot a film in Vietnam (Rising Above: Women of Vietnam, 1995) and was the only filmmaker to film Egyptian protest singer Sheikh Imam in his home and neighbourhood (The Singing Sheikh, 1991).