On Old and New Images

On the Inability to Deal with Old Forms

Sometimes images present themselves with the force of necessity – or should I say inevitability? I naturally saw a film like Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers coming – I think in retrospect! – for quite some time. Sooner or later, all those images lying around will become entangled.

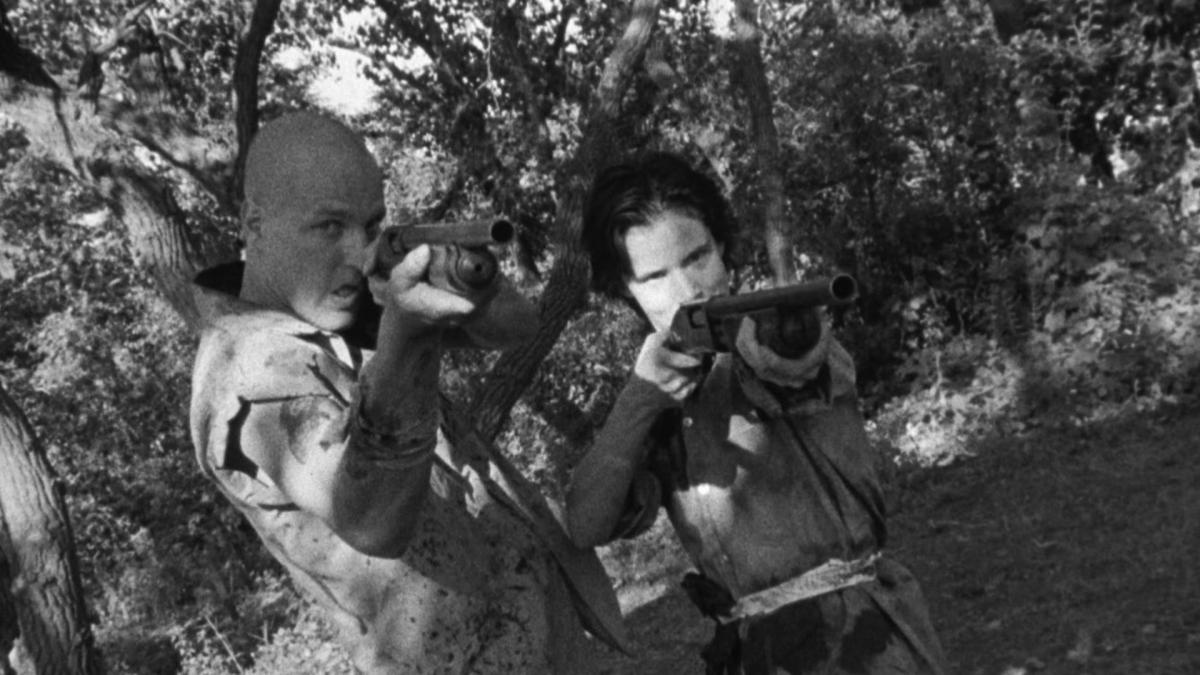

Only now is popular cinema starting to work with the multitude and especially the variety of camera images. Stone mixes quite a few of them, pitting them against each other, letting them fight it out among themselves in a pandemonium that literally and verbally portrays the serial killings. Film, video and animation images, black-and-white and colour, hand-held camera and steady shots, tilting close-ups, coarse grain and overexposed, alongside well-lighted and clean shots. As if, with each device he deployed, Stone were making a different film, and then just edited them all together in short images.

The end result is images whose nature and qualities are unclear. They are all camera images indeed, yet their construction, potence and status are extremely different.

In any case, these kinds of images have absolutely nothing to do with the usual two main types: classic and modern images. Classic film images give us unproblematic access to the world. Modern images, on the other hand, oppose that hypothesis. They show that the image is always mediating, in a decisive way. They make clear that images do not provide a view through but offer aspects. Classic cinema assumed that there is an angle from which a scene can be filmed and edited as a matter of course: clarity exists as an ideal. The moderns, on the other hand, argue that such ideal clarity does not exist; one must always choose between possible solutions. The gaze at what is represented is an integral part of what is represented.

Today’s memorable images (and Stone’s opening sequence is impressive) do not pretend to address such issues and certainly do not want to function as a view through. On the contrary, their images are a shield. The new film images seem blocked; one cannot see through them. One does not look at actors, objects, landscapes; one can barely get the story told. Admittedly, these films no longer want to achieve the two classic goals (looking and telling). What do they want to achieve? In any case, these images demand all the attention for themselves. At the expense of what is happening, it seems.

The latter is curious. Because the actions told are violent, extremely kinetic, hysterical and explosive. How do you film action? By surveying the whole from afar on a hill, or by following the recommendation of the photographer Capa who once said, “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you weren’t close enough.” Goodbye to the era of stuntmen demonstrating acrobatics in wide shots! From now on, one cuts small-frame shots from the action. Many of these shots are shown in such a way that they can deliver their signal at a fast pace. Everything will then take place between the images, no longer within them. Images face other images: their clashes, frictions, and fixes determine everything. Images follow from other images (they used to come one after the other). Images are brutally juxtaposed. This presses them into an increasingly violent straitjacket that holds them together, at least for the duration of the film.

The considerable loudness of the sound accompanies that compulsion towards perfection. Apart from that, the images are clipped into fractions, whereby they gain hysterical strength. Since they must reveal their raison d’être in a flash, they do so loudly and devoid of any nuance. Finally, these images are deployed in very simple dramatic oppositions and edited according to simple poetic-rhetorical structures: contrast, rhyme, echo, repeat. Their unity is above all musical-choreographic.

As early as the 1960s and 1970s, the Italian westerns and the films by Peckinpah showed something similar: an absurd imbalance between image treatment (filming and editing) and scenic labour (the work with actors on set). The cause of this development is never an external factor (one sometimes hears references to music videos) but a dynamic within the film medium itself.

One needs only to watch other films – Loach (Ladybird), Newell (Four Weddings) and Nichols (Wolf) – to experience their misery in life-sized form. None of them remember how to use the old forms – classic and modern. In Four Weddings – a classically filmed comedy – I was struck by one brief shot of a yawning old man during the “funeral”. You understand right away that the makers no longer even knew what extras are: they knew no better than to ridicule him in an exasperating candid shot. Such camera naturalism is fatal to the comic tone. Nichols filmed Wolf, a film of the fantastic genre, in the Scope format he loves and uses just as Truffaut did in the 1960s: lyrically showing wide, freely breathing spaces. A space that hangs around characters and story like far too loose a suit, while the genre calls for a tight image.

The hysteria of desperate images suddenly seems to make more sense to me. No one seems to be able to create images with a mood, a temper of their own, a subtle tonality that should echo what is happening in the image, as I understand it. The images no longer echo what they show. No matter how hard Stone hits: nothing vibrates. However carefully others try not to hit loudly, it is to no avail. It no longer works.

Images from Natural Born Killers (Oliver Stone, 1994)

This text originally appeared in Kunst & Cultuur, vol. 27, December 1994.

Many thanks to Reinhilde Weyns and Bart Meuleman

With the support of LUCA School of Arts, LUCA.breakoutproject