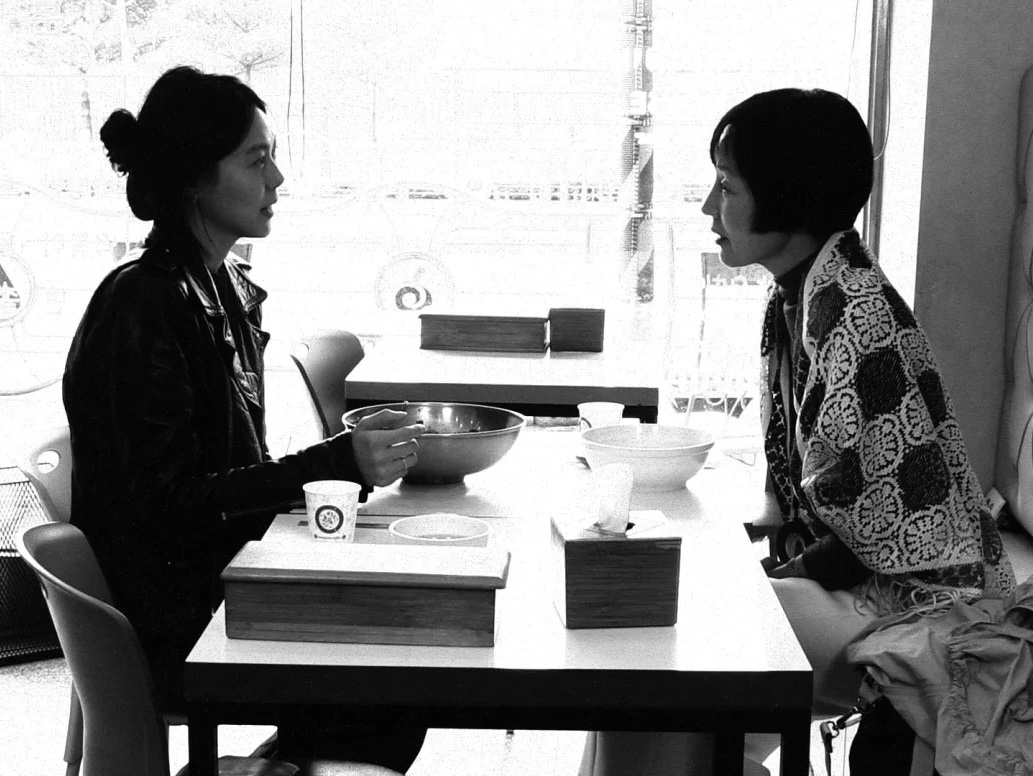

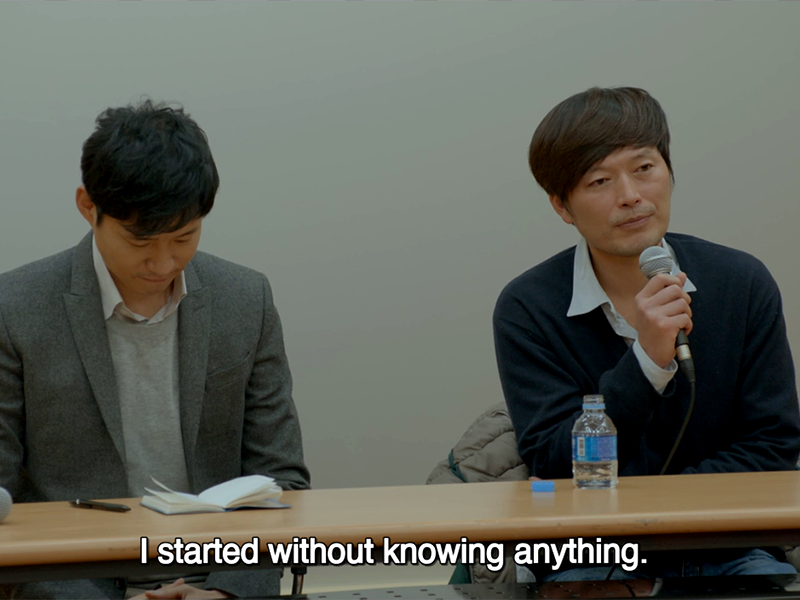

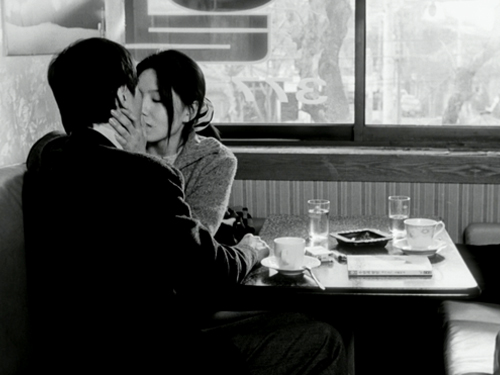

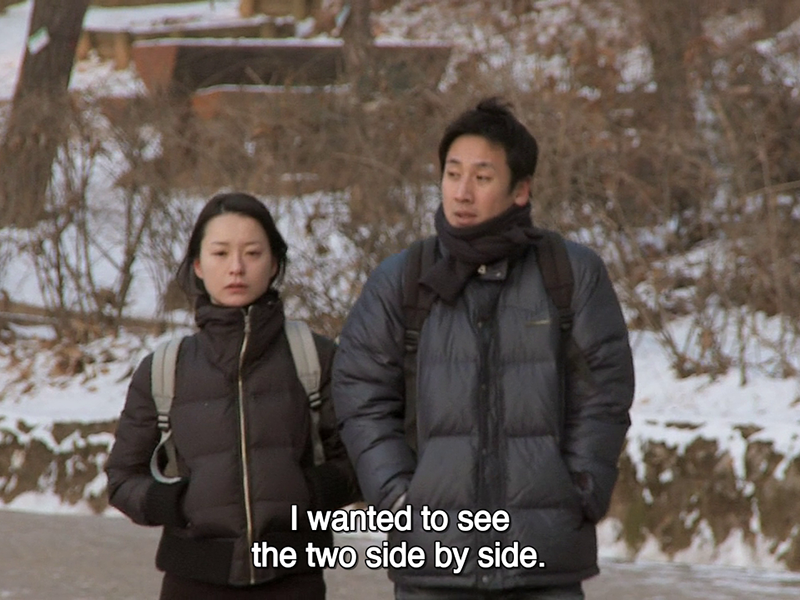

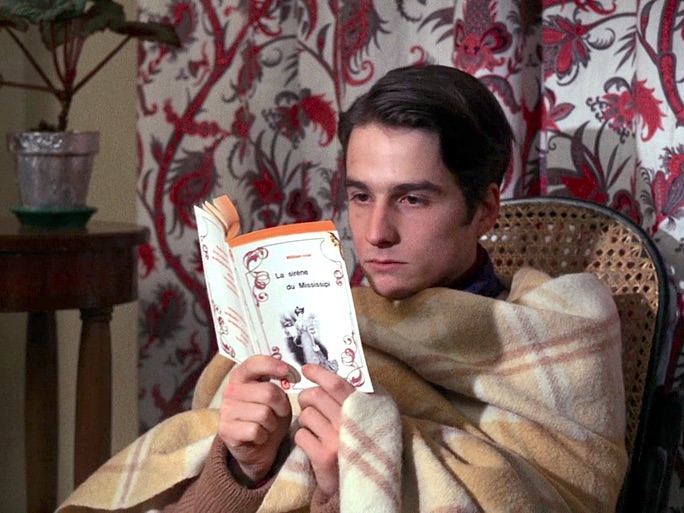

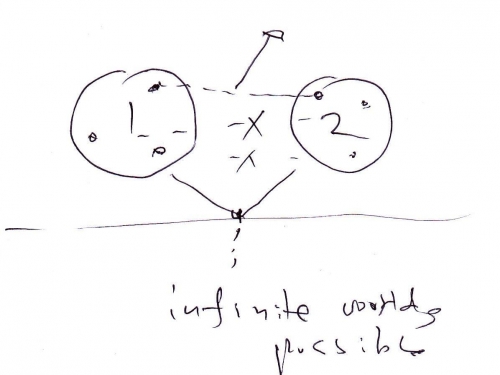

More than most, Hong’s films command attentiveness. Shots, motifs, objects, dialogue, and events return, often transmogrified in their second appearances […] come back as narrative or temporal markers, or even as consequential characters, leaving a viewer to feel like David Hemmings in Blowup, scrutinizing Hong’s every image for clandestine signifiers. Placement in the frame is also paramount, as ostensibly casual groupings turn out to be extremely deliberate in their composition – meant to signal social unease, deceit, or shifting allegiances. […] (That Cézanne, a proto-Cubist, is one of the director’s artistic touchstones is no surprise; Hong, like Bresson, another of his formative influences, is a metteur en ordre – an imposer or maker of order, a finder of hidden forms.)