Out of the Shadows

Assia Djebar

Can it be simply by chance that most films created by women give as much importance to sound, to music, to the timbre of voices recorded or captured unawares, as they do to the image itself? It is as though the screen had to be approached cautiously and be peopled, if need be, with images seen through a look, even a short-sighted, hazy look, but borne on a full, commanding voice, hard as stone but fragile and rich as the human heart.

Assia Djebar (1936-2015) was born Fatima-Zohra Imalayen in Cherchell, Algeria, to a family of Berber origin. She was the first Algerian woman to attend the École normale supérieure de jeunes filles outside Paris. During the Algerian War of Independence (1954-1962), she worked with Frantz Fanon for the newspaper El moudjahid, conducting interviews with Algerian refugees in Tunisia and Morocco, before going on to teach history in Rabat and later in Algiers. Between the ages of twenty and thirty, she wrote four novels. But in the mid-1960s, she decided to abandon writing in French, the language of Algeria’s colonizer. Cinema offered her new ways to approach language as well as the world of the women in her home region, which sharpened her attention to sounds spoken and sung. “I made the decision to make a first film, not knowing really if I’m a filmmaker, I think in November 1975: because it was the day of Pasolini’s death. His relation to popular poetry, to the spoken dialects of these regions, which he has conveyed in a certain way on the screen, is what I felt concerned about.” To film The Nouba of the Women of Mount Chenoua in 1975-77, Assia Djebar went back to the mountain of Chenoua in order to listen and give voice to the oral histories as transmitted by otherwise silenced women. The film was awarded with the Critics’ Prize at the 1979 Venice Film Festival, but was received with hostility in Algiers, where it was considered as too “personal” and thus anathematic to the nationalist project of decolonized Algeria. In 1980, she resumed her career as a writer with Women of Algiers in Their Apartment, a collection of stories expressing Algeria’s collective memory through polyphonic narratives by female voices. This book was going to be the seed for a film on the urban women of Algiers, intended to complement its other half on the rural women of the hinterland. Instead, for what turned out to be her final film, The Zerda or the Songs of Oblivion (1978-1982), she spent two years sifting through archival footage shot by French colonizers in the first half of the 20th century, weaving it into an alternative vision of the history of the Maghreb. As Assia Djebar grew to be one of the most important figures in North African literature, she con- tinued to raise the issue of women’s language and the circulation of women’s voices, all the while developing what she has termed her “own kind of feminism”.

Jocelyne Saab

Once you’re holding a camera, it’s your profession that matters...Maybe, as a definition, and fundamentally I don’t know, you react with a gaze that doesn’t linger on the surface of things, of guns or armies; I have always preferred getting to know people’s sensibilities in great detail, the children, the women, the men, the daily life of human beings... In this field, people are so surprised to see a woman arrive on set that they make room for her and respect her.

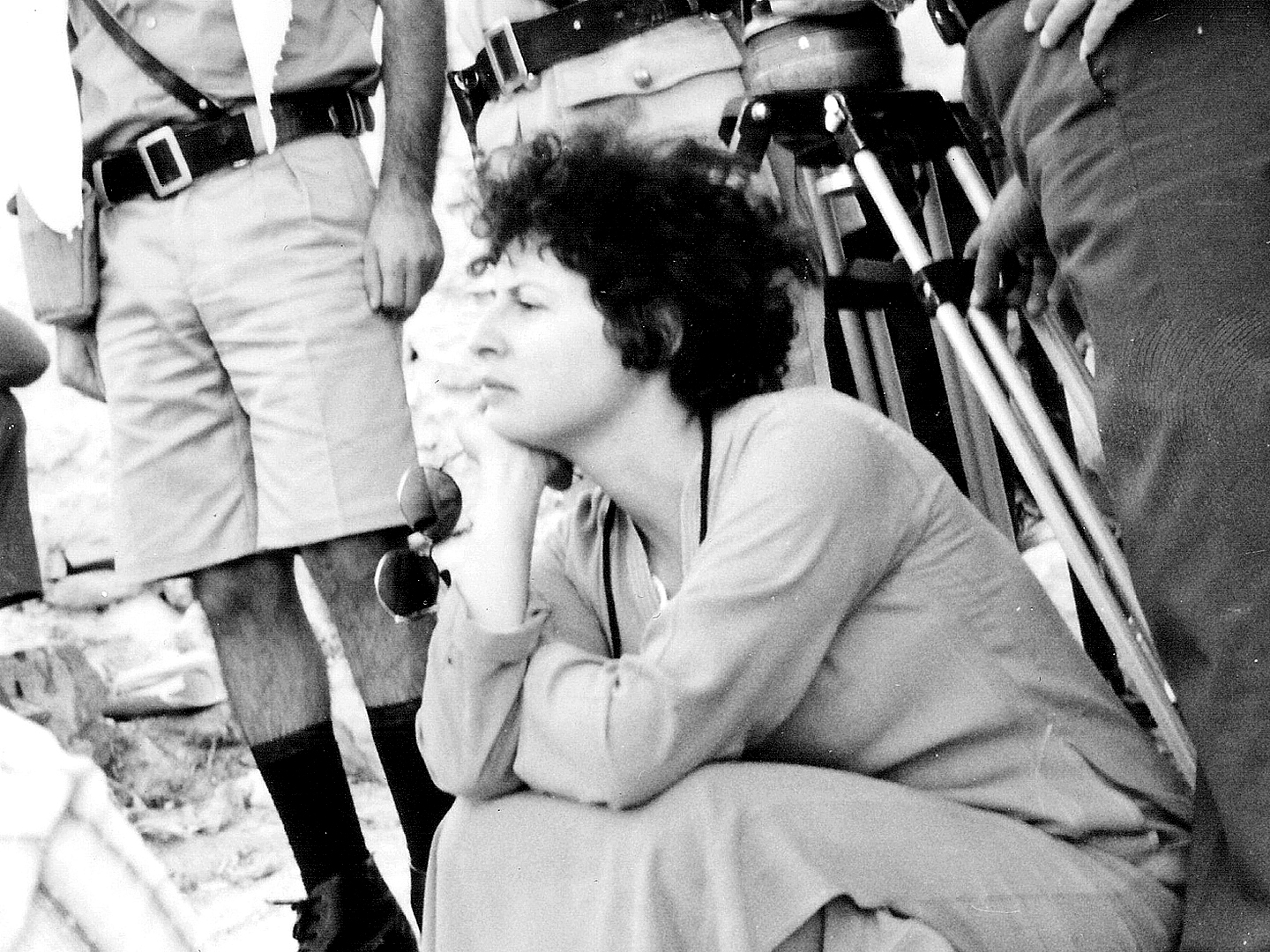

Jocelyne Saab (1948-2019) was born and raised in Beirut. After completing her studies in economic sciences at the Sorbonne in Paris, Saab worked on a music programme on the national Lebanese radio station before being invited by poet and artist Etel Adnan to work as a journalist. Unlike most war reporters, who must travel to war zones to pursue their profession, war came to Saab’s native Lebanon in 1975, and that same year saw the beginning of Saab’s filmmaking career with Lebanon in a Whirlwind, an account of the various forces and interests behind the incipient conflict. The war would last another 15 years, and Saab’s chronicling of its horrors — particularly in her remarkable “Beirut Trilogy”, comprising Beirut, Never Again (1976), Letter from Beirut (1978), and Beirut, My City (1982) — is unequalled in both its ethical integrity and emotional impact. The same candour and empathy Saab applied to the war in her homeland can be found in her other documentaries. Filming the struggle of the Polisario Front in the desert of Western Sahara, the consequences of the infitah on Sadat’s policy in Egypt, or the aftermath of the Iranian revolution of 1979, a picture of a Middle East removed from reductive simplifications emerged through the polyhedral prism of her camera. “I believe that what makes up the specificity of my trajectory is that I have always wanted to remain coherent; I have always been ready to fight for what I believe in, to show and analyse this changing Middle East that I’m so passionate about. Yet the day came when I grew tired of it, or rather my eyes grew tired. I couldn’t see anything anymore — there had been too many deaths and too much suffering. I then moved on to fiction.” Her entry into fiction filmmaking came in 1981 when she worked as second unit director on Volker Schlöndorff ’s Circle of Deceit. Shortly after that, she directed her first fictional work, A Suspended Life (1985), set in the same war-torn Beirut she had documented ten years prior. After the war reconfigured the whole country, in Once Upon a Time in Beirut (1994), Saab tried to rescue the cinematographic memory of the Lebanese capital in the same year that cinema turned 100 years old. In 2005, she was censured and her life threatened for making Dunia, Kiss Me Not On The Eyes, a film shot in Cairo about desire, pleasure and female sexuality in the context of Islam. Until her death in January 2019, Jocelyne Saab remained devoted to what she called her “two permanent obsessions: liberty and memory”.

Texts

Heiny Srour

Those of us from the Third World have to reject the idea of film narration based on the 19th-century western bourgeois novel with its commitment to harmony. Our societies have been too lacerated and fractured by colonial power to fit into those neat scenarios. We have enormous gaps in our societies and film has to recognize this.

Born in 1945 in Beirut, Heiny Srour studied Sociology at the French University of Beirut (Ecole Supérieure des Lettres) and went on to study Social Anthropology at the Sorbonne in Paris, where she was a student of both Marxist sociologist Maxime Rodinson and anthropologist filmmaker Jean Rouch. In 1969, while pursuing a PhD on the status of Lebanese and Arab women and working as a journalist for AfricAsia magazine, she discovered the struggle of the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf, which led an uprising in the province of Dhofar against the British-backed Sultan of Oman. Determined to make a film about this feminist movement, she spent two years doing intensive research and finding the necessary funds before setting out to Dhofar. From the Yemeni border, Heiny Srour and her team crossed 500 miles of desert and mountains by foot, under bombardment by the British Royal Air Force, to reach the combat zone and record the only document shot deep inside the Liberated Area. The Hour of Liberation was completed in 1974 and selected at Cannes Film Festival, making Srour the first woman from the Third World to be selected at the prestigious international festival. Including four years of restoration, this documentary took, all in all, ten years of her life. It took her six years to achieve her next film, Leila and the Wolves (1984), in which she unveiled the hidden histories of women in struggle, in particular in Palestine and Lebanon, by weaving an aesthetically and politically ambitious tableau of history, folklore, myth and archival footage. In her words: “Why shouldn’t women be ambitious? Because men only want women to exclusively deal with women’s issues like home, family and so on, they want to ghettoize us. I resent this. We should deal with the public affairs and political issues too.” Since initiating a feminist study group in Lebanon in the early 1960s, Heiny Srour has been vocal about the position of women, in particular in Arab societies. She has written and spoken extensively about the image and role of women in Arab cinema. In 1978, along with Tunisian filmmaker Selma Baccar and Egyptian film historian Magda Wassef, she co-authored a manifesto ‘For the Self-Expression of the Arab Woman’, remaining passionately active in her feminist advocacy to this day. More recently, she shot a film in Vietnam (Rising Above: Women of Vietnam, 1995) and was the only filmmaker to film Egyptian protest singer Sheikh Imam in his home and neighbourhood (The Singing Sheikh, 1991).

Selma Baccar

I consider what I do as, primarily, bearing witness to my society by way of cinema, with everything that it comprises regarding the contradictions between man and woman, law and practice... I don’t isolate the problem of women from the whole of the society.

Selma Baccar was born in Tunis in 1945. After college, she studied psychology from 1966 to 1968 in Lausanne, Switzerland. At the age of 21, Baccar began to create films with other women at the Hammam-Lif amateur film club. Her first short film, made in 1966, was a black-and-white film called The Awakening that tackled women’s emancipation in Tunisia. She moved to Paris to study film at the Institut de Formation Cinématographique (IFC), after which she worked as assistant director for Tunisian television. In 1975, the same year as the UN’s International Women’s Year, Baccar directed her first feature film titled Fatma 75, which is considered to be the first feature film directed by a woman in Tunisia. In this “analytical film”, as Baccar has defined it, three generations of women and three forms of awareness are related — the period between 1930 and 1938 and the creation of the Union of Tunisian Women; the period between 1939 and 1952, which marks the relationship between the national struggle for independence and the women’s struggle; and finally, the period after 1956 to the present, concerning the achievements of Tunisian women with regards to the Code of Personal Status. “I conducted a series of historical researches, in particular on the participation of women in the struggle for independence and its achievements. I then measured the gap between the Code of Personal Status and its application in practice. Through this film, I wanted to demystify what is called “the miracle of the emancipation of Tunisian women”. Despite being funded by the Tunisian government, Fatma 75 was censored and subsequently banned from screenings in the country for thirty years. In 1990, she became the first woman producer in Tunisia with her production company Inter Médias Production. Selma Baccar’s activism for Tunisian women’s rights led her to an active political career. She also sat on the Assemblée Constituante that rewrote the Tunisian constitution in 2011 to include changes that were heralded by the UN as “a breakthrough for women’s rights”.

Atteyat Al-Abnoudy

I don’t want to be labelled a women’s filmmaker because I make films about life, and women are only a part of this life. I make films about people who I know, who I relate to (class-wise speaking) – humble and poor people. About their struggle to live, about their joy, and about their dreams. I still learn from them, from what they are doing and of their wisdom about life. I give the floor to my people to speak out. That is why they call me ‘the poor people’s filmmaker’.

Atteyat Al-Abnoudy (1939-2018) was born Atteyat Awad Mahmoud Khalil into a family of labourers in a small village along the Nile Delta. A child of Nasserism, she studied law at the University of Cairo while supporting herself financially by working as an actress and assistant director at the theatre. At the beginning of the 1970s, she decided to study film at the Cairo Higher Institute of Cinema, where she created Horse of Mud, which was not only her first film but also Egypt’s first documentary produced by a woman. Her graceful focus on the disadvantaged and the unrepresented in Egyptian society would earn her the nickname “the poor people’s filmmaker”, but it also enkindled a confrontation with censorship. “The censors didn’t like to show the people as very poor after twenty years of revolution in Egypt. They think cinema, especially documentary, should be propaganda for the state. In a way, it’s the fault of the filmmakers who were making documentaries over the past twenty years. They made at least eleven films about the construction of the Aswan High Dam, but they spoke only about the machines, the tractors, the engineers. Nobody talked about the working people who died and suffered to help build this Dam.” Despite its limited circulation, Horse of Mud went on to win numerous international prizes, after which Al-Abnoudy made her graduation film, The Sad Song of Touha, a portrait of Cairo’s street entertainers — which she created in collaboration with her husband, poet and song- writer Abdel Rahman Al-Abnoudy. She continued her studies at the International Film and Television School in London until 1976 and persisted to document the daily lives and struggles of economically and socially marginalized groups in Egypt, while exposing the structural inequalities within the socio-economic system. In films such as Permissible Dreams (1983) and Democracy Days (1996), she attended to the lot of Egyptian women, a choice of subject matter which has fre- quently invited the displeasure of government authorities. Against the grain, Atteyat Al-Abnoudy managed to produce more than thirty films which were shown worldwide, albeit rarely in her own country. Before her death in 2018, she left her film estate to the Cimatheque — Alternative Film Centre in Cairo, which continues to advocate her legacy of independent and committed filmmaking.

All of us, all of us who come from the world of women in the shadows, are reversing the process: at last it is we who are looking, we who are making a beginning. – Assia Djebar

Exploring a cinematic history as extensive and rich as that of the Arab Mediterranean, one is faced with an exhilarating range of forms and manifestations. From the era of silent film up to the present, the regional cinema cultures of the Maghreb and the Mashriq have produced a myriad of remarkable works. Yet, when poring over the canonical historiographies of cinema, one cannot help but being struck by their relative obscurity, which is even more striking when it comes to films that have been made by women. Although there has been a notable rise of Arab female film directors in recent decades, the work of many pioneers tends to remain painfully neglected.

The Out of the Shadows film programme, originally conceived for the Courtisane festival 2020 in Ghent, was intended to revitalize the work of a diversity of filmmakers whose films remain overlooked and barely screened. Five of these filmmakers are presented in this Dossier: Atteyat Al-Abnoudy, Selma Baccar, Assia Djebar, Jocelyne Saab and Heiny Srour. Coming from different backgrounds and regions, these filmmakers all began to produce films in the 1970s, at a moment of great political and cultural ferment. Often working against the grain, they set out to attend to voices and stories that were at risk of being drowned out by official History. While each of these filmmakers developed their own bold approaches to cinema, their works explore shared themes such as memory and identity, oppression and liberation, violence and exclusion, and the social and political role of women in Arab societies and histories. Each of these filmmakers has been shaped by different traditions and realities, for the Arab woman filmmaker exists no more than the Arab woman. Accordingly, this programme seeks to follow Assia Djebar’s appeal “not to presume ‘to speak for’ or, even worse, to ‘speak on’, barely speak near to, and if possible, to speak right up against”. In this vein, this Dossier brings together a selection of writings and interviews that speak “right up against” the films in the programme. The texts, most of which have been translated for the first time in English, are a testament to the women’s singular practices. They have been brought together here, right up against one another, in the hope of illuminating their rich and inspiring work and widening its reach and appreciation.

Stoffel Debuysere (Courtisane) and Gerard-Jan Claes (Sabzian)