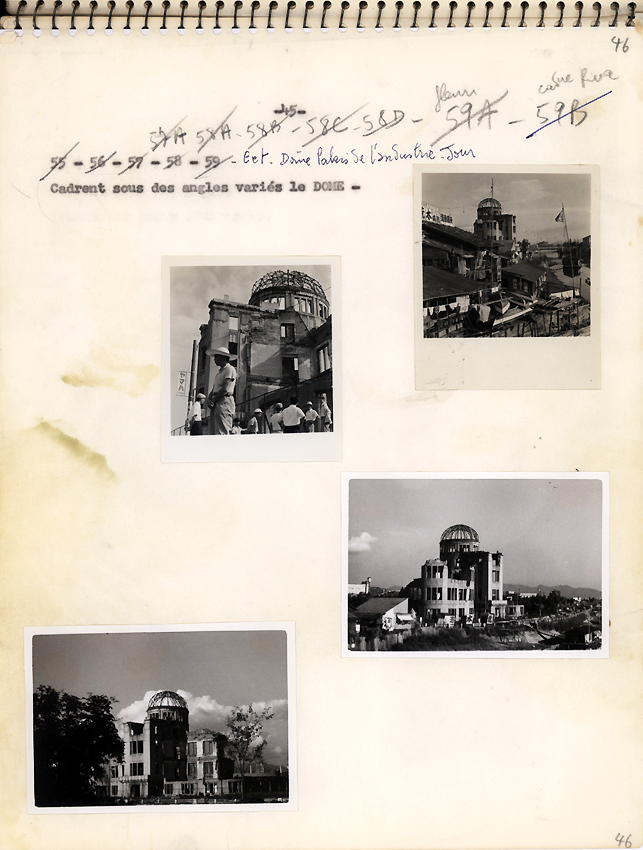

A French actress filming an anti-war film in Hiroshima has an affair with a married Japanese architect as they share their differing perspectives on war.

EN

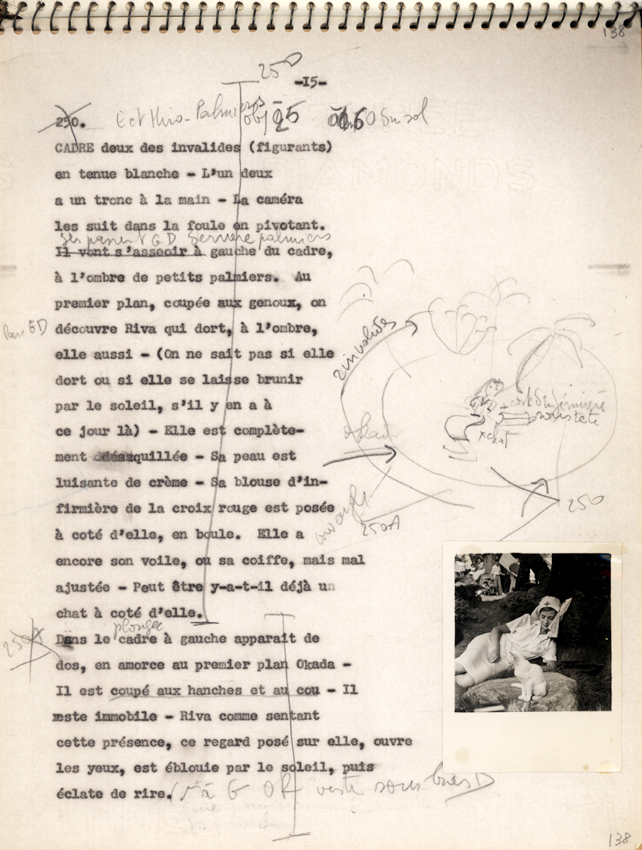

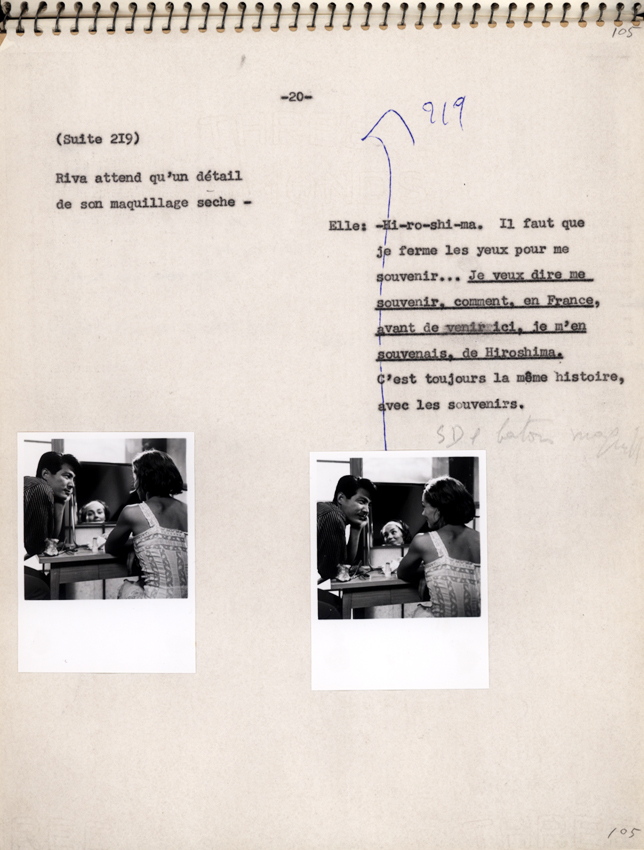

“As the film opens, two pair of bare shoulders appear, little by little. All we see are these shoulders—cut off from the body at the height of the head and hips—in an embrace, and as if drenched with ashes, rain, dew, or sweat, whichever is preferred. The main thing is that we get the feeling that this dew, this perspiration, has been deposited by the atomic “mushroom” as it moves away and evaporates. It should produce a violent, conflicting feeling of freshness and desire. The shoulders are of different colours, one dark, one light, Fusco's music accompanies this almost shocking embrace. The difference between the hands is also very marked. The woman's hand lies on the darker shoulder [...] A man's voice, flat and calm, as if reciting, says:

He: You saw nothing in Hiroshima. Nothing.

She: I saw everything. Everything”

Marguerite Duras1

“There is, needless to say, an imbalance between the singular death of a German soldier and the mass slaughter of Japanese civilians by the atomic bomb. But Duras’s emphasis — even at this early stage of her cinematic evolution — lies on the voices of her principal players. Throughout Hiroshima Mon Amour we hear Riva and Okada in voiceover, speaking in halting sentence fragments: he asking her questions, she carefully composing a récit of her past life and her reaction to the Hiroshima of the present. This isn’t ordinary conversation, nor is it dramatic speech of the standard “realistic” sort. It’s closer in many ways to opera, and Duras’s scrupulous choice of words coupled with her keen awareness of their aural impact reaches a crescendo in the film’s finale. “You are Hiroshima,” Riva says to her Japanese amour, to which Okada responds: “And you are Nevers — Nevers in France.” Thus individual lives are bound to the fate of nations.

Quite heady stuff for 1960. Even more so today, when serious, formally challenging motion pictures about major modern history are virtually unknown. Duras’s interests, however, weren’t historically bounded any more than they resembled “real life” as it is commonly conceived. For through her films, Duras created a world all her own, committed to exploring emotional states at their most rarefied and extreme. And while it may look to the casual observer something along the lines of the world we know, it’s in actuality as abstract as a science-fiction fantasy or a surrealist dreamscape.”

David Ehrenstein2

“Resnais' flashbacks are so organized and interwoven with the narration in the temps réel as to annul the normal time perspective and to create an effect of simultaneity. We are immediately reminded of Cubism which also dismantles the object, even destroys it, in order to permit us to see it in a new perspective, from different points of view at the same time, by recomposing it according to a new law. Resnais dismantles and mounts anew the traditional reality in order to create a new concept of time which is to traditional reality what the new love, in its intense moments (Nevers and Hiroshima), is to the traditional love in the protagonists' état civil.”

Wolfgang A. Luchting3

- 1Marguerite Duras, Hiroshima mon amour (New York: Grove Press, 1961).

- 2David Ehrenstein, "Intense Vocalization: Marguerite Duras", Film Comment, 2014.

- 3Wolfgang A. Luchting, "Hiroschima, Mon Amour, Time, and Proust", The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Spring, 1963), pp. 309-310.

FR

“Le tragique est tout d’abord formel et même très simple: unité de temps (les flash-back sont faits sur un mode racinien du récit), unité historique. Mais le film de Resnais renouvelle le tragique par sa manière de traiter le temps, avec cette confrontation continuelle de l’instant (la possession et le monologue initial par exemple), de la durée psychologique (la course vers le soldat allemand), du temps vécu de la rencontre et du temps historique lui-même. Bref, il y a le déchirement significatif entre l’instant tragique (la même revelation amoureuse à quinze ans de distance) et le devenir dramatique (le film est une longue quête, un patient et douloureux travail de recuperation).”

Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe1

- 1Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, "Notes sur “Hiroshima mon amour” d’Alain Resnais", Positif, Nr. 584, 2009, p. 69.